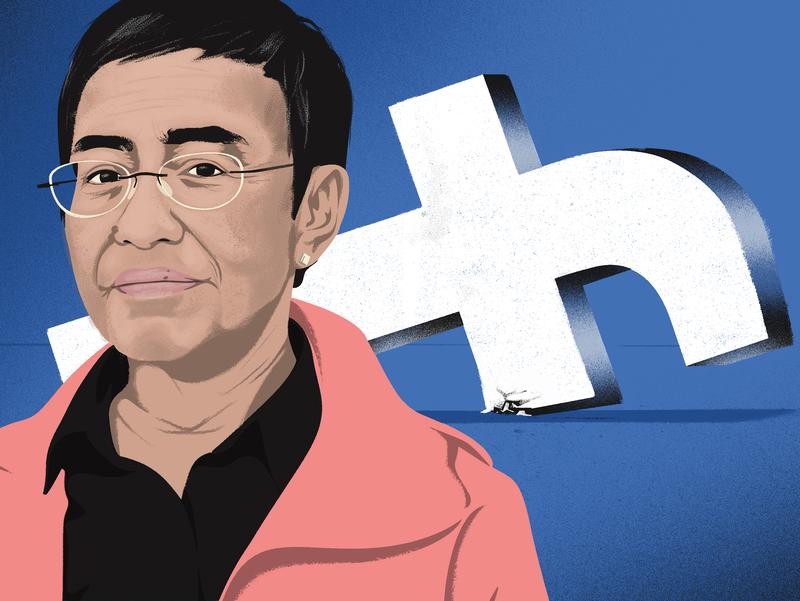

The Nobel Prize Winner Maria Ressa on the Turmoil at Facebook

Speaker 1:

This is The New Yorker Radio Hour, a co-production of WNYC Studios and The New Yorker.

David Remnick:

Welcome to The New Yorker Radio Hour, I'm David Remnick. The trickle of bad news about Facebook, or as its just been rebranded Meta, has turned into a torrent. Weeks ago we learned that the company knows that Instagram, for example, which it owns, causes serious mental distress for many teenagers. In the release of thousands of company documents, known as the Facebook Papers, contains a staggering number of missteps and misdeeds. Facebook's indifference to how it accelerates the circulation of toxic and false information, its participation in corroding civil and democratic society are now just impossible to ignore. The journalist Maria Ressa shared a Nobel Peace Prize in October for her work to protect freedom of expression.

Maria Ressa:

Hi.

David Remnick:

Here we are. Maria, how are you?

Maria Ressa:

Oh, good. It's one of those days of cascading meetings...

David Remnick:

Ressa runs the digital news organization Rappler, which is based in the Philippines, and she's been the target of hate campaigns by supporters of President Rodrigo Duterte over and over again. At first, Ressa believed Facebook would be critical to the success of her enterprise in journalism in general, but she soon became one of Facebook's most vocal and informed critics. I want to read to you something that you've said and I want to expand on it. You said this, "I think that the rollback of democracy globally and the tearing apart of shared reality has been because of tech. It's because news organizations lost our gate keeping powers to technology and technology took the revenues that we used to have, and they took the powers, but they abdicated responsibility." These revelations have made clearer, they've been, it's clear to many but clearer what the problem is with Facebook and social media in the way you've been describing it. I guess the next question we have to ask is what is to be done? To repeat the famous question.

David Remnick:

Facebook, not to do their work for them, but Facebook would charge to the microphone and say, "Look, we have spent millions upon millions of dollars to do better. We've essentially hired a kind of supreme court to adjudicate some of these difficult questions and hired and brought in some extremely prestigious minds from the world of journalism and academia and all the rest. We have tried to strip away as much hate speech as we possibly can, but it comes in a torrent and we can't get everything." Do you have any sympathy for this argument?

Maria Ressa:

None.

David Remnick:

None. So go ahead.

Maria Ressa:

None, you know, and I get it on both ends, right? Because what Facebook has enabled is an environment where my government has been able to file 10 arrest warrants against me in less than two years. Okay. Now Facebook, these companies didn't set out to be news organizations. So they actually don't have standards and ethics or the mission to protect the public's sphere. But that's also where regulation must come in, because that is exactly what they're doing. These platforms are the connective tissue of society. These platforms determine our reality. They exploit the weaknesses of our biology to actually shift behavior, to shift the way you think if the way you think shifts, then the way you behave shifts, right. January 6th is a perfect example of that, right? So I don't even know where to begin.

David Remnick:

You're doing great. Keep charging on. Go ahead. You said January 6th was a perfect example.

Maria Ressa:

Well, again, was that a surprise for any of us who live on Facebook? It wasn't because we were seeing this, so think about it like, sorry, I'm going to do three assumptions that the platforms do that just drive me crazy as a journalist. The first is that, if you don't like something, if a lie is told about you or if you just don't like something, mute it. If it's a lie that is tearing down your credibility does muting it help. Number one. Number two, that more and faster is better. It really isn't and that's part of it. I think the kind of friction that is necessary to stop the spread of lies isn't even in the calculation, because that's not in the design. And then I think the third part is that all of us have our own realities. Which democracy can survive when you have almost 3 billion Truman Shows and we are each performing not to mention the impact on the individual who is performing, right? So the shift in behavior is real and it is exploited by governments like mine.

David Remnick:

If Facebook is incapable of, for all the reasons we know of dealing with this torrent, the next step is the government in some way, being in charge of that. And I think both you and I were raised to think that the government being in charge of determining what is fact and what is not fact and what is legitimate speech and what is hate speech is complicated to say the least.

Maria Ressa:

But that's not what they should be doing. It's not about content and that's where you run into the free speech issues, right? Because that's downstream. Go upstream to the problem, the design of the platform, there must be radical transparency for what is going into these algorithms that are determining our realities. So if you go there, you bypass this. Why are fake accounts being allowed to proliferate at the scale that they do? Even as early as 2017 Facebook's footnotes in its disclosure said that the Philippines had more than the normal average of fake accounts. So they know an account is fake. So it's like playing a whack-a-mole game. Legislation should deal with fraud. It should deal with the same laws that the actions that are illegal in the real world should be mirrored in the virtual world, right? You don't have to recreate reality. You don't have to have new definitions.

Maria Ressa:

Part of our problem, I think is that we're trying to find new words for that algorithmic bias, because in the end while the platforms will say, the algorithms are a machine, they are programmed and they reflect the biases of the programmer, which is also why my country is... Coded Bias, I don't know if you saw that film, right? There's an MIT student who couldn't do an AI experiment until she put a white face on because of the coded bias. So that's part of the problem is that these American social media platforms, these American companies have exported their bias and it is insidiously built into our Philippines, any other country's information ecosystem.

David Remnick:

A lot of people are calling for the breaking up of Facebook and for Mark Zuckerberg, if not to step down entirely to be in charge of a realm of Facebook that would be much diminished. How do you look at that problem and would that solve anything?

Maria Ressa:

I don't know the right answer to that, right? Because I do think that we're a Facebook country, the Philippines. 100% of Filipinos on the internet are on Facebook. I believed in the power of Facebook before they betrayed my beliefs, but when we started Rappler in 2012, a rallying cry, we asked people to go on Facebook, a rallying cry was social media for social good. Social media for social change. I had hoped that we could use technology to jumpstart development and build institutions bottom up.

David Remnick:

So you feel betrayed by that?

Maria Ressa:

Yeah, I was naive, right? I didn't think that the money... I mean because in the end they're using a scorched earth policy, the same way that the Duterte administration is using a scorched earth policy. The generation after is going to have to pay for everything that's been done now. That's the same thing that Facebook is doing. It doesn't make sense unless the money in the short term is worth it for them. Let me put it this way.

David Remnick:

Well, do you believe that Mark Zuckerberg and Cheryl Sandberg and company blundered into the problems that they've gotten now, or they knew all along exactly what they were doing and didn't care?

Maria Ressa:

I can't call them evil, at least not yet. Because that's kind of what it is. That is it that surveillance capitalism is can you do it even if people are dying. Although I ask this question all the time, who you is responsible for genocide in Myanmar? It isn't just the military. It isn't just the groups that seeded that or the killings in the Philippines, which were enabled. They changed reality. They saw it coming, but by digging in his heels and I guess you go back to Mark Zuckerberg and the kind of power he has. When I met him, I was struck by how smart he's... He is intelligent, David, you know like he knows the technology, but what he didn't realize, I think was the impact of this. He looks at it in terms of do you remember that quote of his, "It's only 1%"

David Remnick:

Yeah. I think what Zuckerberg was getting at is his claim that less than 1% of what's on Facebook is fake news.

Maria Ressa:

1% of how much is how much and what is the impact of that? For a journalist, one error is too much, right? So it's kind of like saying, "Oh, well, we can have some poison in the environment. Let's say it's in our body, we can have poison in there, but that poison spreads and it will kill.

David Remnick:

It's 1% cyanide in your dinner.

Maria Ressa:

Yes.

David Remnick:

Maria, do you extend your critique of social media to Twitter and Google as well as Facebook equally?

Maria Ressa:

I do, but each platform is different. So I will say for Search, right? The page ranking I mean, if you look at all of the things that are there it's better thought out. It has a lot more inputs into it, and they're a more transparent.

David Remnick:

We're talking about Google now?

Maria Ressa:

Yes. Google Search. YouTube on the other hand could do with a bit more, right? In the Philippines, YouTube is now number one. Twitter in the United States is different from the Philippines. I feel more protected on Twitter than I do on Facebook and that's why you'll see me there more than I am on Facebook, even though Facebook is essentially still our internet.

David Remnick:

Was the initial conceit the original sin. In other words, the original conceit of Facebook was we are not a publisher, we are merely a platform. We're providing a global Hyde Park corner where everybody can say what they want and exchange information when they want. Was that the original sin?

Maria Ressa:

I think the original sin was when they got rid of... You know it worked really well when it was Facebook and they had you had to have your campus ID, you knew who you were and the newsfeed was chronological. That's the first, right. Then they tweaked it over time and the newsfeed is now no longer chronological, the personalization part. That it's a tech construct again. Is personalization... Think about it David, did that make sense that you are given everything you want, that your cognitive bias is fueled by more of what you want? Is that really the right thing? I think this is part of the reason our values have... Our world has slightly turned upside down because we've adapted this hook line and sinker, personalization is better. Oh yeah. Okay. Well, it does make the company more money, but is that the right thing? Because personalization also tears apart a shared reality.

David Remnick:

Maria Ressa runs the news site Rappler in the Philippines. There's more to come today on the deep and frightening problem of misinformation that's affecting democracies all over the world, including our own. This is the New Yorker Radio Hour, stick around.

David Remnick:

This is the New Yorker Radio Hour, I'm David Remnick. I tend to think that real life is scary enough, especially these past few years, without having to gin up new scares for Halloween. But some of you I know have spent the whole month of October binging on scary stories, ghost stories, and zombie stories and serial killers with saws and hockey masks and candy. So before that's all over, we've got another one for you. Here's staff writer, Andrew Marantz, on the horrors of the internet, real and imagined

Andrew Marantz:

Human beings have always liked scary stories. And there is pleasure in a scary story that is totally made up in a hypothetical land far, far away. But I think we all know from experience that the scariest kind of story are the ones where you think maybe some part of this could possibly be real. This is something we've understood throughout the history of telling scary stories. For example, one of the first horror novels was called The Castle of Otranto was published in 1764. It's obviously fictional, right? It's about a haunted castle in Italy, but there's this preface to the book where the author says, "Actually, what you're about to read is real."

Narrator:

The following work was found in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the North of England. The scene is undoubtedly laid in some real castle.

Joe Ondrak:

And then from there you can trace a really rich history of every time there's been a new step in communication and mediation, horror stories been there to play with it.

Andrew Marantz:

This is Joe Ondrak. Joe is an expert in scary stories in fact, he's working on a doctorate in them.

Joe Ondrak:

You know, you have the mass produced popular novel, and you have things like Dracula and the first edition of Frankenstein were both published as this epistolary, maybe fact made be fiction.

Narrator 2:

The sun does not more certainly shine in the heavens than that which I now affirm is true.

Joe Ondrak:

From there you can trace it to things like the famous War of the Worlds broadcast in radio which again was playing with it.

Speaker 8:

There's a jet of planes flying [inaudible 00:16:09] at least right at the [inaudible 00:16:09] men. It strikes them head on. Lord, they shooting at the plane.

Joe Ondrak:

And then most famously you have the Blair Witch Project and the revolution in handheld cameras.

Heather:

Oh, we're doing a documentary about the Blair Witch.

Speaker 9:

Oh.

Speaker 8:

Oh, have you heard of the Blair Witch?

Speaker 9:

Oh yeah. That's an old, old, old story.

Joe Ondrak:

So my whole thing that I absolutely love with text has always been this teasing at the balance between fact and fiction. And it just seemed like a natural progression to study creepypasta.

Andrew Marantz:

Let's just pause on that word for a second. The word Joe just said is creepypasta. So yes, creepy as in scary pasta as in noodles. It is admittedly a really silly word, but this is the internet and often totally silly words can refer to things that are actually worth paying attention to.

Joe Ondrak:

So the very, very basic version of creepypasta is it is a form of horror fiction that is written on the internet for the internet.

Andrew Marantz:

So the way creepypasta works is it uses things like social media or online forums, YouTube even, as tools in telling the story. And not only can you take it in by reading it or watching it, you can also participate in it. If all that feels a little academic, maybe it's easier to just look at one concrete example, a creepypasta that Joe really likes it's called Candle Cove.

Joe Ondrak:

So Candle Cove is an interesting example because that one, it was originally published online as a fiction. So it was originally written by a chap named Kris Straub on his website.

Andrew Marantz:

Okay. I have it. I just pulled it up here, subject Candle Cove local kids show. Does anyone remember this kid show? It was called Candle Cove and I must have been six or seven. Okay. So it just starts like that. I never found reference to it anywhere. So I think it was on a local station around 1971 or 1972. I lived in Ironton.

Joe Ondrak:

So the original Candle Cove narrative in a nutshell is a message board exchange between a few different people reminiscing about a children's television show.

Speaker 11:

Was it about pirates? I remember a pirate marionette at the mouth of a cave talking to a little girl.

Andrew Marantz:

So again, just to be clear, this is a fictional story that is written in the form of message board discussions about a fictional TV show. So as these characters are reminiscing about this show, they then start to remember these more and more upsetting details.

Speaker 11:

And the puppets and the marionettes were flailing spastically and just all screaming, screaming. The girl was just moaning and crying like she had been through hours of this.

Joe Ondrak:

Before a final twist that's one of the four members goes to visit his mom in nursing home.

Speaker 12:

I asked her about when I was little in the early '70s when I was eight or nine and if she remembered a kids show, Candle Cove. She said she was surprised I could remember that and I asked why. And she said, "Because I used to think it was so strange that you said I'm going to go watch Candle Cove now, mom. And then you would tune the TV to static and just watch dead air for 30 minutes. You had a big imagination with your little pirate show.

Andrew Marantz:

So basically some people read this story on this spooky website and either because they think it would be a funny joke or because they want to mess with themselves or for whatever reason people do things on the internet. They then copy that text, they go to some other website, which could be an actual web forum about actual old TV and they repost the story there. And then you start finding that the new people, the people who are newly exposed to this start to believe it.

Joe Ondrak:

Yeah, or at least start to give the appearance that they believe it. And from there a more interesting development happened, which is, as it gained popularity people started to create videos of what they thought Candle Cove the show would actually look like.

Andrew Marantz:

So suddenly you have people creating a real show that you can actually watch on YouTube that looks like the fake show that was being described in that fictional, scary story.

Joe Ondrak:

That's the moment where things really start to get destabilized in terms of facts or fiction.

Andrew Marantz:

Because in some sense, then there is a TV show or a video or something called Candle Cove that does exist in the world.

Joe Ondrak:

Yeah.

Andrew Marantz:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). Well, so to that point as you say, trying to participate in stories or warp the boundaries between fact and fiction is old as the horror genre itself. What about the internet gives people new tools to play with those boundaries that didn't exist in film or novels or whatever?

Joe Ondrak:

So one of the big ones is that the network's internet purports to give this immediacy in interaction between people. It's a communications medium first and foremost, that is direct between different real people. So the spreads versions of Candle Cove that were posted to various different forums, they looked entirely like another real person, real posts and experiences. And social media, the internet in general produces such a volume of information that we have to rely on what's essentially an implicit social contract that what is on there is representative of our real lives or truthful to a certain extent. And creepypasta leverages this trust in order to derive its affect, its horror scare comes from the fact that we can't verify every piece of information out there and we have to trust that to a certain extent what is on there is true.

Andrew Marantz:

So here's where our scary story about scary stories actually starts to get a lot scarier. So, but in addition to being a grad student studying creepypasta, you also have a day job, is that right?

Joe Ondrak:

So I am head of investigations for a company called Logically. We are a tech company that deals specifically with disinformation campaigns and fake news and navigating information in the social media landscape that it is today.

Andrew Marantz:

Probably not what most literature PhDs end up working in?

Joe Ondrak:

Not really but I somehow managed to bridge that gap and it's been a pretty seamless transition.

Andrew Marantz:

Logically is one of many companies that have recently cropped up that try to combat the spread of hate and disinformation online. This was a whole industry that didn't really exist 10 years ago and is now a pretty big deal.

Joe Ondrak:

In 2016, just as I was about to start my PhD, the term fake news became front page news. I realized that they are using the exact same in mechanics and the exact same ways in which people engage with fictions to get people to believe far more malicious things.

Andrew Marantz:

So what about them look similar and what are the dynamics that you recognized?

Joe Ondrak:

So creepypasta is interactive because you can not only read it, but you can then choose to copy and paste it and tell it yourself. The same thing can be true of a disinformation narrative. So things like claims around COVID cures or various different claims from take any conspiracy theory of your pick really. When we encounter it for the first time, what we see is 95% of the time not going to be the origin of that particular claim or that particular narrative. It's more than going to have been adjusted or remixed through the lens of others have been posting it. And that there's still another aspect of overlap, which is the obscuring of origin. A good creepypasta is one that you encounter 30 spreads away from the origin poster. Whereas disinformation campaigns will do their best to obscure any seed post or origin around it. And again they take off when people are repeating it and spreading it and remixing it for their own receptive audiences. Now a good example of this is the Frazzledrip narrative.

Andrew Marantz:

So that's another weird word. The word is Frazzledrip. It's just a made up word that was supposedly the name of a video file found buried on Anthony Weiner's computer hard drive, Frazzledrip.

Joe Ondrak:

It's this rumored video of Hillary Clinton conducting an actual child sacrifice. QAnon talks about Hillary Clinton being part of this Satan pedophile elite and this story is told almost as a creepypasta by believers of Qanon. So it's either, oh, I saw this video or my friends saw this video and then they describe it in graphic and intense detail.

Speaker 13:

What exactly could bring hardened NYPD detectives to vomit and cry? Just reading some details is cause for nightmares, truly horrific nightmares. No one wants to see this video.

Andrew Marantz:

There were already a lot of people who hated Hillary Clinton, but if you were a person who hated Hillary Clinton, and then you came across a very specific story like Frazzledrip, and it's one that is using all the same literary techniques that we have been talking about to make you believe that not only is Hillary Clinton politically bad, but she's literally a satan-worshiping child trafficker. That is the kind of thing that can really heighten the urgency of the situation. So now you're not just someone who wants to talk about how much you dislike Hillary, but you could become someone who thinks there is a crisis happening in the real world, and that you need to go out and do some about it. Think Pizzagate, or think January 6th. For people who are sort of sitting at home going, well, what can we do about this? Do you think that you guys can fix it or like what's the next step here?

Joe Ondrak:

I don't think fixing it is on the cards. We at Logically and other initiatives to combat disinformation can help people recognize and navigate the sheer amount of information online the way in which to say, because it offered the route doesn't lie with considering it as information. It lies in considering it as narratives that people would want to believe and will then repeat and embody and then tell others. So the larger question then around fixing this issue becomes, why do these people want to believe this?

Andrew Marantz:

So it could be frustrating or baffling, frankly, to think about how anyone could believe such obviously false things that Hillary Clinton and Oprah and Tom Hanks are all in some satanic cult together or whatever the conspiracy theory is. And talking to Joe kind of made me think that it might be less important, whether a story is true than whether it's engaging, whether it hooks into our mind, whether it's enjoyable to think about or play around with. And as Joe said this way of blurring the line between fiction and reality, it's a great way to make a scary story more enjoyable, more participatory, and the internet has made those lines extremely blurry.

Andrew Marantz:

At this point, you can pretty much live inside a largely fictional universe. You can tell yourself that your opponents are actually inhuman monsters and that boring everyday politics is actually a showdown between the eternal forces of good and evil. Now in most cases, that's probably not true, but it might be engaging. And once you're fully engaged in that story, it might start to seem sensible to do something really drastic or even violent. And that is a very scary story, one that happens to be true.

David Remnick:

Andrew Marantz is a staff writer for the New Yorker and his book on online extremism is called Antisocial. We also heard from Joe Ondrak, who's a researcher for the tech company, Logically. This is the New Yorker Radio Hour with more to come. I'm David Remnick and you're listening to the New Yorker Radio Hour. In 1965, 5 years after Nigeria gained its independence, the playwright Wole Soyinka was already known as an opposition figure. Authorities falsely accused him of armed robbery and before the country's civil war at the late '60s, Soyinka tried to avert fighting. He was accused of aspiring with rebels and was then imprisoned by the Nigerian government.

David Remnick:

He's a writer with an astonishing history of putting himself on the line for his political and social commitments. Soyinka has received the Nobel Prize for Literature. He's written more than two dozen plays, a vast amount of poetry, several memoirs, essays, and short stories, and just two novels. His third novel is out now nearly five decades after the last one, it's called Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, it's both a political satire and a murder mystery. It involves four friends, a secret society dealing in human body parts and more corruption than anyone country can bear. Staff writer, Vinson Cunningham spoke to Wole Soyinka at his home in Nigeria.

Vinson Cunningham:

I really want to talk to you about Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, a title that I love. I heard that you've been thinking about this story for many years now. How does it feel to have it out in the world?

Wole Soyinka:

It's been a little bit overwhelming, I think I wasn't expecting this kind of reception of it. I mean, it's just part of my own creative continuum in a different format like taking time off from theater to write a novel.

Vinson Cunningham:

Yeah. This is your third novel and of course you're known most prolifically for your works of theater, but what is it that the novel does for you that theater doesn't? This change in form are there necessities that it meets that theater doesn't and vice versa? What's the form about for you?

Wole Soyinka:

What the novel does for me as a medium of expression is to assuage the masochist in me because the novel is very taxing, taxing in the sense that it's tempting to go in so many directions. Theater for me is more focused when you're a narrator and you're juggling a number of characters and they insist on wandering very willfully in directions which you did not preview and then you forget where you last saw them and so. I know I really praise novelists, those whose media is a novel. They have a hard time at it.

Vinson Cunningham:

Yeah. I mean, but you do in this way, and it's interesting to hear you talk about them as in some ways willing themselves, but you offer us this total panoply of great characters. There's a crooked religious leader, there is a politician, sort of earnest diplomat, a famous doctor. In the course of writing this book, was there a favorite character that you aligned on? Was there one who was especially willful and sort of surprised you in different ways?

Wole Soyinka:

Well, there's no question at all that a number of the characters were "inspired or triggered" into being by personal encounters but to great pains to ensure that some of the villains knew that they provided the base material and in fact, I've even met one of them since the novel came out. And come up to me and I said, "Well, you're coming to me I hope you realize that you were this in the novel." And he was a politician and like a good politician said, "Oh, prof that's okay but I really want to discuss a certain issues with you in the novel, forget my character." So the novel does give one that latitude I must confess and then it can play variations far more than in theater. I think theater is almost pre-rigged. By that I mean, they're more constricted in case of the theater.

Wole Soyinka:

And that is one of the reasons why tackling a theme like this human tumult in which I've been existing, watching others survive, me too surviving in my way. Watching that deterioration of society, the novel intuitively struck me as the only medium in which I could actually purge myself of this oppressive sense of a society going haywire.

Vinson Cunningham:

No, it's interesting there is this sense, this dark sense of as you say, a society going haywire and it's contrasted against this wonderful title, you know the land of the happiest people on earth. Now, I heard that this was inspired by the "World Happiness Report" where Nigeria was rated one of the happiest countries in the world. First of all, is that true? And what did that reality, if so, what did that present to you artistically?

Wole Soyinka:

Well, when I saw that World Report I thought, look at these people laughing at us. Why are they so cruel? Why they doing this? And then I realized it was supposed to be a serious poll, a serious estimate, supposed to be objective and analytical, even scientific. And so I looked into this, I said, "Maybe I'm in the wrong place." But when I looked around it was still a society which I recognized as my own, as one of which I function. So it stuck in my head for quite a while, this was some years ago. And when I began working on it, it actually began with other titles. Eventually I suddenly realized, oh, wait a minute. That estimation, that analysis is the exact title I've been looking for.

Vinson Cunningham:

You know, happiness is such a fraught idea. Here in America, of course, we've sort of encoded it into our national myth. You know, the pursuit of happiness has all these echos.

Wole Soyinka:

Yes. Yes, indeed.

Vinson Cunningham:

What does it mean for you? Because of course it can be totally vapid, fun-seeking, surface sort of Epicureanism, I guess. But it can also speak to a real joy. What does it mean for you and why did it fit so well?

Wole Soyinka:

It fits so well of course, because it's an irony. This country, the people in this nation are not the happiest by no strength of imagination. And yet at the same time if they went deep enough into society I think they would flee or consign destination to the place to be during your what's that season of yours when you hang skeletons all over the place near November.

Vinson Cunningham:

Halloween.

Wole Soyinka:

Halloween, maybe this is Halloween nation and then one can understand it. But then again, as I was saying, you do encounter those two extract, possibly a measure of contentment, of full fulfillment even though the most meager kind they're buoyed either by religion or by an ingrained traditional philosophy that the worst is yet to come and therefore you better enjoy the present. Because Nigerians do celebrate I mean, that is not a lie. And those people all over the world where Nigerians are, they do salute Nigerians for their spirit of celebration. Which is why I took pains to ensure that at least one character represented what the pursuit of happiness might be through creativity, through just love others, through just making others happy if only for a few moments. So it's a mishmash of ironies, of acknowledgement, of concession, of even a measure of salute to the people. I hope that measure comes out, that element comes out.

Vinson Cunningham:

Speaking of this issue of happiness and the different places where it can be found or not found you know where it can be promised, but not delivered perhaps. One of those is religion and a lot of this book turns on a kind of an upswing in religious fundamentalism. Is it okay if I read a very short passage that I just love from this book? It's about a preacher who we get to know better on his name is Papa Davina, and he has this epiphany, he's on this kind of long comic journey across West Africa. We see him in Liberia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and he's in Ghana and he has this epiphany. He's just kind of made this pun on the word, a site of prophesy or prophet site. And he says this, "He looked nervous to around hoping that no one else had caught that creative slip or at least that it had not registered with anyone in that audience with apostolic ambitions.

Vinson Cunningham:

The flash momentarily unnerved him as it inserted profound doubts in his mind. Could it be that he was after all the genuine article? That he'd indeed responded to an authentic call to prophecy, prophesite. Why had all his predecessors failed to formulate such an exquisite indeed mellifluous name for a place of spiritual quest? Could it be that he was unbeknownst to himself till now truly called." This person who's clearly a charlatan of a kind, but almost convinces himself that he's not in certain ways. I wanted to talk to you just about this emphasis on fundamentalism. What role did that play for you?

Wole Soyinka:

You know some of the greatest charlatans of religion, of the religious profession are really very likable people, very lovable people. First of all, they're performers. They enjoy performing. Now, if you enjoy what you're doing, you are a happy person and you infect others with some of that happiness. So even while you are, you know blathering platitudes and knowing very well that you're conning your congregation, you do produce not just happiness, sometimes rupture, genuine, authentic rupture. And so I find very complex people, the genuine religionists, of course some of them are just sinister, the fundamentalists, for instance, both of Christianity and of Islam and Hinduism, for instance, you have the fundamentalists. All religions have their fundamentalist sectors and those are really sinister, dangerous people.

Wole Soyinka:

They have no sense of humor. They cannot see the pathetic side of life. They cannot even look at themselves in the mirror and give themselves a pat on the back and say, you charlatan, but today wasn't bad. They're incapable of it. Some of them just kill the belief that's it. You kill anybody who doesn't aspire to your level of malevolent conviction.

Vinson Cunningham:

I'd love to talk to you about, over the course of your career and I feel career is not as capacious a word as I want. You've been able to bring your activism and your intellectualism and your sort of art all onto the same plane, all operating at once. I learned that and please correct me if I'm wrong is Fela Kuti your cousin?

Wole Soyinka:

Fela?

Vinson Cunningham:

Yes.

Wole Soyinka:

Yes. My cousin. Anikulapo, of course. Yes.

Vinson Cunningham:

I had not known that and it struck me as so apt because here was another person whose art and intellect and political sense were all inter-implicated all together. I wonder if just your upbringing made you feel that as a responsibility? Was that a natural step for you to be sort of an activist, politically aware, a true citizen in the deep sense of that word, and also an artist at the same time?

Wole Soyinka:

It remains a mystery to me. And why should it be a mystery? It's because basically I would rather not be all these things, in other words an activist. I ask myself, I don't know how often, how on earth did you get on this path? Why don't you just stick to what you really love doing? Just writing bit poetry, writing plays, directing plays, exchanging ideas, getting into arguments simply because we live also with obstructions and anybody who believes in the essence of things, the theory of things loves the discourse about them. And this I enjoy, which is also why I'm also a teacher by profession. I would rather be doing all those things, honestly, but I end up using that expression a closet masochist for myself, because I'm doing certain things which I know I would rather not be doing, but I also love my peace of mind, my tranquility, and I cannot attain that.

Wole Soyinka:

That's a contradiction. I know I cannot attain that if I have not attended to an issue, a problem which I know is pernicious, which I know is manifesting itself in a dehumanizing way in others, whether human beings, environment, child abuse, for instance. So we're not just talking about politics we're just talking about humanity that this is one of me. I remain restless when I see such situations and the only way I can attain that peace which I love so much and which I only very sparsely enjoy that's what drives one out again and again and again. Using other means when once literature fails one, fail to address the issue, then of course you have to address it frontally, physically by whatever means.

Vinson Cunningham:

Yeah. I love how you just said that your pursuit of Tranquility has in some ways required that you get yourself into trouble in these other ways. It seems like there's not much glory to be had among your own people when you are confronting them in this way. It seems like a fraught position just on a personal level, have you made peace with that or is it a constant?

Wole Soyinka:

It's a constant if I'm to be at peace with myself, I confront the unacceptable from whichever side. Of course the state has certain statutory responsibilities so the state gets it more than the people themselves.

Vinson Cunningham:

I love a quote in your book there are two friends who really form the heart of this book, who are speaking at one point and one of them delivers one of the book's most affecting lines for me. He says, "Something is broken beyond race, outside color or history something has cracked, can't be put back together." That's something that sort of ineffable something that's beyond all of the ideology and all of anything that we can put our finger to. I wonder if writing this book helped you put a name to that ineffable something and have maybe the politics of the last few years helped you to identify or reconsider what it might be?

Wole Soyinka:

You know, I've tried to put my finger on it and I end up with a question, what is human? And I think that's what we've lost. It has gone on for too long, that condition of losing what is human. From the most profound aspects of our relationships to the most trivial we lost what is human.

Vinson Cunningham:

As a way to say goodbye we mentioned Fela Kuti, your late cousin do you have a favorite song of his?

Wole Soyinka:

My favorite is "Zombie." The reason actually is one that's not appreciated by most people, that song "Zombie" applies not merely to the military in terms of their conduct into the people in this nation, but "Zombie" and that is what Nigerians have not yet realized, they have become mimic people. They act like zombies, they expect orders even if those orders are intolerable. They develop habits that they should not develop. So when I hear "Zombie" I see not merely SARS, those murdering police. I see not merely the bullying soldiers I see also what Nigerians have become. So I enjoy "Zombie" on many more levels than the average Nigerian does.

Vinson Cunningham:

Thank you so much. This has been wonderful and I really appreciate.

Wole Soyinka:

You're welcome. Thank you.

David Remnick:

Staff writer Vinson Cunningham speaking with Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka. His new novel is Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth and that's it for us this week. And if you missed anything from today's program, you can find it all on the podcast of our show, wherever you listen to podcasts. I'm David Remnick, thanks for listening. We'll see you next time.

Speaker 1:

The New Yorker Radio Hour is a co-production of WNYC Studios and the New Yorker. Our theme music was composed and performed by Merrill Garbus of tUnE-YArDs with additional music by Alexis Cuadrado. This episode was produced by Alex Barron, Emily Botein, Ave Carrillo, KalaLea, David Krasnow, Ngofeen Mputubwele, Louis Mitchell, Michele Moses, and Steven Valentino.

David Remnick:

And we had additional help from Priscilla Alabii and Harrison Keithline.

Speaker 1:

The New Yorker Radio Hour is supported in part by the Charina Endowment Fund.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.