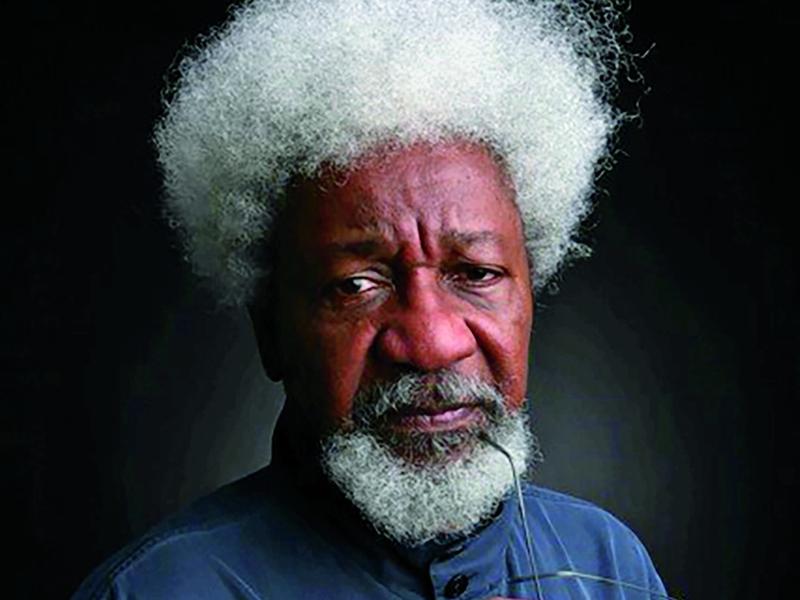

Wole Soyinka on His New Satire of Corruption and Fundamentalism

Speaker 1: In 1965, five years after Nigeria gained its independence, the playwright Wole Soyinka was already known as an opposition figure. Authorities falsely accused him of armed robbery. Before the country's civil war of the late '60s, Soyinka tried to avert fighting. He was accused of conspiring with rebels and was then imprisoned by the Nigerian government. He's a writer with an astonishing history of putting himself on the line for his political and social commitments.

Soyinka has received the Nobel Prize for Literature. He's written more than two dozen plays, a vast amount of poetry, several memoirs, essays, and short stories, and just two novels. His third novel is out now, nearly five decades after the last one. It's called Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth. It's both a political satire and a murder mystery. It involves four friends, a secret society dealing in human body parts, and more corruption than any one country can bear. Staff writer Vinson Cunningham spoke to Wole Soyinka at his home in Nigeria.

Vinson Cunningham: I really want to talk to you about Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, a title that I love. I heard that you've been thinking about this story for many years now. How does it feel to have it out in the world?

Wole Soyinka: It's been a little bit overwhelming, I think. I wasn't expecting this kind of reception of it. It's just part of my own creative continuum in a different format. It's like taking time off from theater to write a novel.

Vinson Cunningham: Yes. This is your third novel and, of course, you're known most prolifically for your works of theater. What is it that the novel does for you that theater doesn't? This change in form, are there necessities that it meets that theater doesn't and vice versa? What's the form about for you?

Wole Soyinka: What the novel does for me as a medium of expression is to assuage the masochist in me-

Vinson Cunningham: [laughs].

Wole Soyinka: -because the novel is very taxing. Taxing in the sense that it's tempting to go in so many directions. Theater for me is more focused. When you are a narrator and you are juggling a number of characters and they insist on wandering very willfully in directions which you did not review, and then you forget where you last saw them and so on. I really praise novelists whose nature is a novel. They have a hard time at it.

Vinson Cunningham: Yes, but you do in this way. It's interesting to hear you talk about them in some ways willing themselves. You offer us this total panoply of great characters. There's a crooked religious leader, there is a politician's earnest diplomat, a famous doctor. In the course of writing this book, was there a favorite character that you aligned on? Was there one who was especially willful and surprised you in different ways?

Wole Soyinka: Oh, there's no question at all that a number of the characters were "inspired" or triggered into being by personal encounters are two great things to ensure that some of the villains knew that they provided the base material. In fact, having met one of them since the novel came out and come up to me and I said, "You're coming to me, I hope you realize that you were this in the novel." It was a politician, and a good politician, said, "Oh, prof, that's okay, but I really want to discuss certain issues with you in the novel about my character.

Vinson Cunningham: [laughs].

Wole Soyinka: The novel does give one that latitude I must confess, and then you can play variations far more than in theater. I think theater is almost pre-written. By that I mean they are more constricted in case of the theater. That is one of the reasons why tackling a theme like this human tumult in which have been existing, watching others survive, me too surviving in my way, watching that deterioration of society, the novel intuitively struck me as the only medium in which I could actually purge myself of this oppressive sense of the society going haywire.

Vinson Cunningham: It's interesting, there is this sense, this dark sense of, as you say, a society going haywire and it's contrasted against this wonderful title, The Land of the Happiest People on Earth. I heard that this was inspired by the "world happiness" report where Nigeria was rated one of the happiest countries in the world. First of all, is that true, and what did that reality--? If so, what did that present to you artistically?

Wole Soyinka: When I saw that poll, that world report, I thought, "Look at these people laughing at us. Why are they so cruel? Why are they're doing this?" Then I realized it was supposed to be a serious poll, a serious estimate, supposed to be objective analytical, even scientific. I looked into this, I said, "Maybe I'm in the wrong place, but when I look round, it is still a society which I recognize as my own, as the one in which I function." It stuck in my head for quite a while. This was some years ago. When I began working on it, it actually began with other titles. Eventually, I slowly realized, "Oh, wait a minute, that estimation, that analysis is the exact title I've been looking for."

Vinson Cunningham: Happiness is such a fraught idea. Here in America, of course, we've encoded it into our national myth, the pursuit of happiness has all these echoes.

Wole Soyinka: Yes, indeed.

Vinson Cunningham: [laughs] What does it mean for you because of course, it can be totally vapid, fun-seeking surface Epicureanism, I guess? It can also speak to a real joy. What does it mean for you and why did it fit so well?

Wole Soyinka: It fits so well of course because it's an irony. This country, the people in this nation, I'm not the happiest by no strength of imagination. Yet at the same time, if they went deep enough in society, I think they would free or consign this mission to the place to be during your-- What's that season of yours when you hang skeletons all over the place in November?

Vinson Cunningham: [laughs] Halloween?

Wole Soyinka: Halloween. Maybe this is Halloween mission and they're not going to understand it. Then, again as I was saying, you do encounter those who extract possibly a measure of contentment or fulfillment. Even though the most meager kind, they are boiled either by religion or by an ingrained traditional philosophy that the worst is yet to come, and therefore you better enjoy the present because now you really do celebrate.

Those people all over the world where Nigerians are, they do salute Nigerians for their spirit of celebration which is why I took pains to ensure that at least one character represented what the pursuit of happiness might be through creativity, through just love of others, to just making others happy if only for a few moments. It's a mish-mash of ironies, of acknowledgments, of concession, of even a measure of salute to the people. I hope that measure comes out, that element comes out.

Vinson Cunningham: Speaking of this issue of happiness and the different places where it can be found or not found, where it can be promised, but not delivered perhaps, one of those is religion. A lot of this book turns on an upswing in religious fundamentalism. Is it okay if I read a very short passage that I just loved from this book? It's about a preacher who we get to know better and his name is Papa Davina. He has this epiphany, he's on this long comic journey across West Africa. We see him in Liberia, Senegal, Sierra Leon, and he's in Ghana and he has this epiphany. He's just made this pun on the word, a site of privacy or profit site.

He says this, "He looked nervously around hoping that no one else had caught that creative slip or at least that it had not registered with anyone in that audience with apostolic ambitions. The flash momentarily unnerved him as it inserted profound doubts in his mind. Could it be that he was after all the genuine article, that he had indeed responded to an authentic call to prophecy, prophesite? Why had all his predecessors failed to formulate such an exquisite, indeed mellifluous name for a place of spiritual quest? Could it be that he was, unbeknownst to himself till, now truly called?"

This person who's clearly a charlatan of a kind, but almost convinces himself that he's not in certain ways. I wanted to talk to you just about this emphasis on fundamentalism. What role did that play for you?

Wole Soyinka: You know some of the greatest charlatans of the religious profession are really very likable people. Very loveable people. First of all, they're performers. They enjoy performing. If you enjoy what you're doing, you are a happy person and you infect others with some of that happiness. Even while you are blabbering platitudes and knowing very well that you are conning your congregation, you do produce not just happiness, sometimes rapture. Genuine authentic rapture. I find very complex people they're genuine regionists. Of course, some of them are just sinister, the fundamentalist for instance both of Christianity and of Islam.

Hinduism, for instance, you have the fundamentalists. All religions have their fundamentalist sectors and those are really sinister, dangerous people. They have no sense of humor, they cannot see the pathetic side of life. They cannot even look at themselves in the mirror and give themselves a pat on the back and say, "You charlatan, today wasn't bad." They are incapable of it. They just solve and just kill. They believe that's it. You kill anybody who doesn't aspire to your level of malevolent conviction

Vinson Cunningham: I'd love to talk to you about over the course of your career, and I feel career is not as capacious a word as I want, you've been able to bring your activism and your intellectualism and your art all on to the same plain all operating at once. I learned that, and please correct me if I'm wrong, is Fela Kuti your cousin?

Wole Soyinka: Fela?

Vinson Cunningham: Yes.

Wole Soyinka: Yes, my cousin. Aníkúlápó, yes of course. Yes.

Vinson Cunningham: I had not known that. It struck me as so apt because here was another person whose art and intellect and political sense were all inter-implicated altogether. I wonder if just your upbringing made you feel that as a responsibility. Was that a natural step for you to be an activist, politically aware, a true citizen in the deep sense of that word, and also an artist at the same time?

Wole Soyinka: It remains a mystery to me. Why should it be a mystery? It's because basically, I would rather not be all these things.

Vinson Cunningham: [laughs].

Wole Soyinka: In other words, an activist. I ask myself I don't know how often, "How on earth did you get on this path? Why don't you just stick to what you really love doing?" Which is writing bits of poetry, writing plays, directing plays, exchanging ideas, getting into arguments simply because we live also with obstructions and anybody who believes in the essence of things, the theory of things loves the discourse about them. This I enjoy which is also why I'm also a teacher by profession. I would rather be doing all those things honestly but I end up using that expression, a closet masochist for myself because I'm doing certain things which I know I would rather not be doing. I also love my peace of mind, my tranquillity and I cannot attain that. That's a contradiction.

I know I cannot attain that if I have not attended to an issue, a problem which I know is pernicious, which I know is manifesting itself in a dehumanizing way in others. Whether human beings, environment, child abuse, for instance. We're not just talking about politics. We're just talking about humanity. This is one of me. I remain restless when I see such situations. The only way I can attain that peace which I love so much, and which I only very sparsely enjoy, that's what drives one out again and again and again. Using other means when one's literature fails one, fails to address the issue, then, of course, you have to address it frontally, physically by whatever means.

Vinson Cunningham: I love how you just said that your pursuit of tranquillity has, in some ways, required that you get yourself into trouble in these other ways. It seems like there's not much glory to be had among your own people when you are confronting them in this way. It seems like a fraught position. Just on a personal level, have you made peace with that or is it a constant?

Wole Soyinka: It's a constant. If I am to be at peace with myself, I must confront the unacceptable from whichever side. Of course, the state has certain statutory responsibilities so the state gets it more than the people themselves.

Vinson Cunningham: I love a quote in your book. There are two friends who really form the heart of this book who are speaking at one point and one of them delivers one of the book's most affecting lines for me. He says, "Something is broken beyond race. Outside color or history, something has cracked. Can't be put back together." That ineffable something that's beyond all of the ideology and anything that we can put our finger to, I wonder if writing this book helped you put a name to that ineffable something. Have maybe the politics of the last few years helped you to identify or reconsider what it might be?

Wole Soyinka: I've tried to put my finger on it and I end up with the question, what is human? I think that's what we've lost. It is gone on for too long, that condition of losing what is human. From the most profound aspects of our relationships to the most trivial, we lost what is human.

Vinson Cunningham: As a way to say goodbye, we mentioned Fela Kuti, your late cousin. Do you have a favorite song of his?

Wole Soyinka: My favorite is Zombie. The reason actually is one that's not appreciated by most people. That song, Zombie, applies not merely to the military in terms of their conduct to the people in this nation. Zombie, and that is what Nigerians have not yet realized, they have become mimic people. They act like zombies. They expect orders even if those orders are intolerable. They develop habits that they should not develop. When I hear Zombie, I see not merely SARS, those murdering police, I see not merely the bullying soldiers. I see also what Nigerians have become. I enjoy Zombie on many more levels than the average Nigerian does.

[music]

Vinson Cunningham: Thank you so much. This has been wonderful and I really appreciate it.

Wole Soyinka: You're welcome. Thank you.

[music]

Speaker 1: Staff writer Vinson Cunningham speaking with Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka. His new novel is Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth.

[music]

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.