TikTok In the Crosshairs... Again. And Saying Goodbye to Jezebel

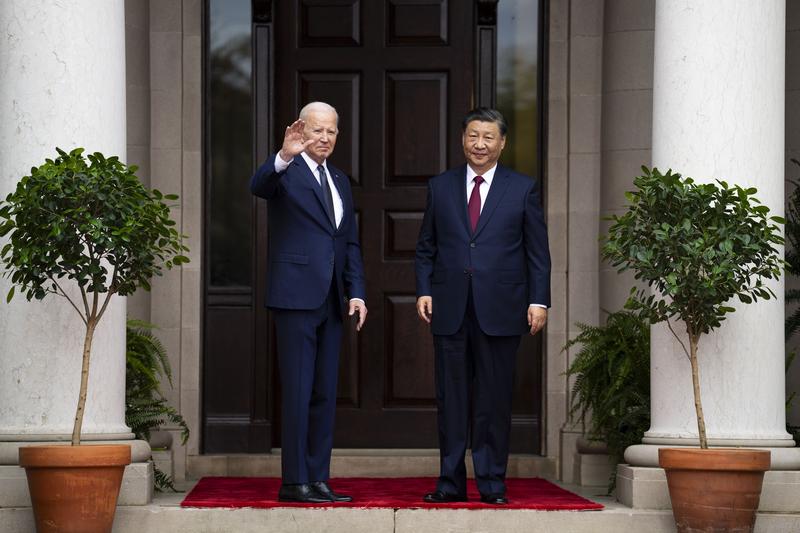

( Doug Mills / AP Photo )

News clip: China's President Xi Jinping spoke positively about meeting President Biden.

Brooke Gladstone: The initial US coverage had a somewhat different take. From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: And I'm Micah Loewinger. On this week's show, the usual calls for TikTok to be banned have increased since the start of the war in the Middle East.

Drew Harwell: People take a hashtag comparison and decide that it's proof of this sinister plot to turn American high schoolers against Israel.

Brooke Gladstone: Also, the long run of the subversively feminist website Jezebel has ended. Founding editor Anna Holmes said that its crucial place in feminist lore wasn't a given at the start.

Anna Holmes: I had mentioned the F-word, feminism, and one of my bosses cautioned me against it. In that moment, and I remember it very clearly, I thought, "Well, I'll show him."

Micah Loewinger: It's all coming up after this.

[MUSIC - Avalon: It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas]

From WNYC New York, this is On the Media. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Earlier this week, presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping came together for a long-awaited meeting in Northern California. Some early coverage suggested that little was gained, but according to who?

News clip: President Biden is touting what he's calling important progress in US-China relations.

News clip: Will reestablish direct contact between our militaries and that China will help take steps to stop the flow of fentanyl into the US.

News clip: China's President Xi Jinping later gave a speech in San Francisco where he spoke positively about meeting President Biden. He also said his country has no intention of challenging the United States.

Daniel Sneider: The meeting really exceeded my expectation.

Brooke Gladstone: Daniel Sneider is a lecturer in East Asian studies and international policy at Stanford University.

Daniel Sneider: Because I think both men were determined to bring the relationship back from the brink of confrontation, avoid conflict, restore communication, both at the highest level, but all the way down through the government and beyond the government.

Brooke Gladstone: This reset was more than obvious in the state-controlled Chinese media. For example, ahead of the meeting, the state news agency, Xinhua ran a long piece in English about the enduring strength of Xi's affection for ordinary Americans with photos of him sitting in a tractor smiling with an Iowa farmer taken on a visit to America in 2012. In fact, some of the people Xi met on that visit were actually present at a dinner with him on Wednesday.

Daniel Sneider: It's an easy way to say, "Hey, I have been your friend. I want to be your friend." Chinese state media is very accomplished and used to doing what's necessary to signal what the Chinese government wants, and they pick up certain, very familiar themes, but also specific events that they've used before. The other one, which again, is not something unprecedented, it was this commemoration of the Flying Tigers, the American volunteer pilots who fought with the Chinese against the Japanese in World War II, even before the US entered the war.

Brooke Gladstone: That was in defense of Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang government, not the communist.

Daniel Sneider: Well, the Chinese Communist Party, when they want to, will take on the mantle of representing all of China, including acknowledging that the China, at that point, was not led by them, but led by the nationalists. They do that when they're looking at wartime history a lot because it also allows them to inherit and claim the place of China as a global leader because you remember during World War II, we had these pictures of Chiang Kai-shek, Roosevelt, and Churchill all together, leaders of the Allied nations fighting the Japanese. The Chinese Communist Party, when it's useful to them, they embrace that legacy of Chinese leadership.

Brooke Gladstone: Xinhua published a five-part series in Chinese on Getting China-US Relations Back on Track. There was a torrent of other articles, and also the press highlighted recent visits to China by the American Ballet Theatre and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Anything else jump out at you in terms of the coverage around or during this event? No photos, I assume, of anti-Chinese protestors in San Francisco.

Daniel Sneider: No. The Chinese coverage of the APEC summit itself, first of all, is meant to focus on Xi Jinping and how well-received he was, and that includes pictures of pro-Chinese demonstrators, which were probably all organized by the Chinese themselves, and no pictures of protestors. The welcoming that he received from the business community, all these things are meant to say Xi Jinping, great leader. He's the one who's setting the tone. Biden is a little bit more the supplicant, if you will, seeking better relation.

That's Chinese propaganda, but I think it's also the case that the Chinese are very clearly signaling, and they did it in their coverage, that they want American investment and trade to come back to China. Chinese are suffering from a serious economic slowdown, recovering from the effects of the COVID epidemic, and the restrictive measures the Chinese imposed, plus the technology war, which the United States has led to restrict the flow of high technology to China, and the efforts of American business and a multinational business to shift their dependence on China to other investment locations, like Vietnam and India.

The Chinese really are in a full-court press to reverse that for their own reasons.

Brooke Gladstone: He also met with a bunch of American CEOs, didn't he? Had dinner with them.

Daniel Sneider: This was a huge event, a whole flood of CEOs, everyone from Tim Cook of Apple to Elon Musk to bankers of various kinds, tech executives from Silicon Valley all marching up there. This was maybe not more important than their meeting with Biden, but close. The speech that Xi Jinping delivered at that meeting was all about, "We need to live together in the same universe. The world's big enough for all of us. We don't want decoupling." Frankly, the American business community are eager to reciprocate.

Brooke Gladstone: But the shift in coverage, who's it for? Some of it, as I mentioned, was in English. Most of it wasn't. Is it for the Chinese public?

Daniel Sneider: It's both. They were signaling to the Chinese population, "Okay, this is our policy. We're not responding to the pressure of the United States. We've made this determination that we need to improve relations. We're putting the pressure on the United States to do that."

Brooke Gladstone: Does he reckon that this may reassure some in the Chinese business community?

Daniel Sneider: Xi Jinping needs to reassure the Chinese people that economic prosperity is going to return. That's essential. Inside the Chinese leadership, there's clearly a healthy debate going on about some of the policy decisions that Xi Jinping has made, backing the Russians, cracking down on Chinese private sector companies that are global actors in the marketplace like Alibaba, things that people see as a retreat from the market reforms that drove China's engagement with the United States and with the West.

Brooke Gladstone: I want to draw a little bit on your historical memory here. These kinds of shifts, you've seen them before.

Daniel Sneider: We saw it when China launched into its reform and opening phase under Deng Xiaoping. China had gone through a long period of the culture revolution of seeing the West as the enemy, the United States as the enemy, and beginning, of course, with the opening by Kissinger and Nixon in the early 1970s, which was an abrupt shift at that time, but it's followed later on when Deng Xiaoping embraces the idea of the market as a driver of the Chinese economy. He makes a very famous visit to the United States. We have these pictures of Deng Xiaoping with a cowboy hat on.

All of these were meant to signal that, "No, we have decided to completely change the way we interact with the United States and the outside world." They've done this more than once, and they've retreated from that as well.

Brooke Gladstone: Let's switch gears and talk about how Western media have been covering the Biden-Xi meeting. I take it you've had some gripes.

Daniel Sneider: Well, we've got this narrative, particularly American media, that we have a relationship that's in free fall, and we're heading to war over Taiwan. There's a whole narrative of threat, of inevitable crisis, and of course, there's some truth to the sense that we are obviously in the midst of a deep confrontation, if you will, but therefore, what happens is you tend to miss these turns because it doesn't fit your narrative.

Brooke Gladstone: Can you give me an example of what you see as the problem in the coverage?

Daniel Sneider: The one that jolted me out of my chair after the Biden-Xi summit meeting was a headline in The New York Times that read, Biden-Xi Talks Lead to Little but a Promise to Keep Talking. The story basically said, "Well, nothing really was accomplished here," and this is this focus on, "Oh, what's the deliverable here? Let me see some concrete things that you've agreed to that really show that there's been some breakthrough in the relationship," when, in fact, of course, the meeting itself is the accomplishment when you have no communication at a senior level for a long time, like more than a year, it has a huge impact.

What both men wanted to do was to demonstrate their ability and their willingness to manage the relationship and to signal that to everyone else around the world. That signal doesn't get through very clearly when you have press coverage, which basically says, "Well, really nothing happened here." The other piece of this that really, I find troubling, is coverage of US-China relations particularly that comes out of the mainstream media, is very shaped by the domestic politics of United States. Everything is in terms of, "Can Biden really do anything? It'll cause problems in his re-election campaign."

It's all focused on Biden in a way that I think misses the point. Xi Jinping wanted this meeting more than Joe Biden did. The really interesting question is, why did Xi come to this meeting? What's going on in China that tells Xi that he needs to do this? The coverage of what's going on inside China is really patchy, and a lot of times, it's just not there. We don't even think about China as a place where they are competing interests, different elements of the Chinese leadership, which may have different views. Now, it's hard to get a hold of that, but it's there.

Brooke Gladstone: Those of us who are casual readers, really just pick up on the chest-thumping.

Daniel Sneider: It makes for good copy but I also see that the media is looking for it. They ask Biden these questions knowing perfectly well sometimes that he has a tendency to say things in a less than precise manner. I saw it during the time of this summit meeting here. At the end of his press conference, a reporter said, "Well, do you still think that Xi Jinping is a dictator?" Well, Biden had said that at one point, and in a typical fashion he said, "Well--"

President Joe Biden: Look, Xi is indeed a dictator in the sense that he's the guy who runs a country that's based on form of government totally different than ours.

Daniel Sneider: I mean, he tried to smooth it out a little bit, but of course, the immediate pickup was Biden calls Xi a dictator.

Brooke Gladstone: So what do you think the Western press should do first to cover the US-China relationship better?

Daniel Sneider: A little more historical context would be good. We tend to view every event as if it's happening for the first time. There's a long history of the US-China relationship. There's more continuity than there is discontinuity. Let's go back to the Tiananmen incident in 1989 when the Chinese murdered many, many hundreds of student protestors against the Chinese Communist Party and the US imposed deep sanctions against China. After all, Bill Clinton ran for the presidency in 1992 talking about the butchers of Beijing.

We've been in moments of serious crisis, we hit it again in the mid-'90s when the Chinese fired missiles to try and influence the elections in Taiwan and the US deployed two aircraft carrier battle groups to the Taiwan Straits. There have been many moments of crisis and we've had to manage those things. I think the big difference between now and then is that in the last 12 years or so since Xi Jinping came to power, Chinese have really begun to see themselves as a great power, asserted themselves as a great power in a way that makes that crisis management a lot more difficult.

There's friends of mine in Japan who said to me they think the two signal moments for the Chinese turn to see themselves as a much more powerful actor than they did before, was the 2008 financial crisis in the US, which really diminished the view of the United States as being the sort of success story economically that China had to follow, and the Beijing Olympics where China emerges in a different kind of way. We're dealing with a bigger, stronger, in some sense, more difficult China, but we have a long history of trying to manage this relationship, realizing our interests are not the same, but they're also overlapping.

I am hoping for a return of more reporters back into China, and this depends on the Chinese more than anybody else, to let people back in and open things back up because we need to see more reporting on the realities of what's going on inside China. That's not convenient for Chinese, but is necessary.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you very much, Dan.

Daniel Sneider: Thank you.

[MUSIC- Skylark: Anita O'Day]

Brooke Gladstone: Daniel Sneider is a lecturer in East Asian studies and international policy at Stanford University.

Micah Loewinger: Coming up, can we really blame TikTok for tipping the scales of public opinion on the Middle East war?

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media.

[MUSIC - Michael Andrews: What's That Sound]

This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger. While news of Biden's meeting with President Xi Jinping occupied this week's front page, another China story continued to simmer in the background. Another social media panic.

News clip: As the war rages on between Israel and Hamas, another battle is being fought on TikTok.

News clip: You have a lot of this pro-Hamas content that is coming across on TikTok.

News clip: China could turn that pipeline on any way it wants.

Micah Loewinger: Republicans in Congress who tried to ban the China-based social media platform last year now argue that TikTok's thumb is on the scale, influencing content about the Israel-Hamas war. Their evidence? Data that quantify the hashtags used on TikTok. Data that seemed to show far more videos with anti-Israel tags than anti-Palestine. FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr.

Brendan Carr: There are lots of reports showing right now that on TikTok, anti-Israel content is trending in some cases 4 to 1, in some cases 15 to 1.

Micah Loewinger: Earlier this month, GOP Representative Mike Gallagher published an essay accusing TikTok of brainwashing young Americans against Israel. He called the platform digital fentanyl and he railed against the disparity in content and what he deemed the obvious guilty party.

Mike Gallagher: If you don't think the Chinese Communist Party could or would weaponize that platform to spread anti-American propaganda, to divide Americans against Americans, to increase division in this country, then you're not paying attention.

Drew Harwell: TikTok has always been susceptible to this criticism. It has always been punched around because it's the lone social network success story of the modern internet that has not come from the United States.

Micah Loewinger: Drew Harwell is a tech reporter for the Washington Post. In an article this week, he wrote about how in the last 30 days, #standwithIsrael, had been used on about 6,000 posts that had been viewed 55 million times in the US. #freePalestine meanwhile had been used on 177,000 posts with 946 million views, nearly 900 million more views for the #freePalestine content. I asked Drew why the big gap.

Drew Harwell: It's a huge gap. The problem with looking at a number like that is there's no proof that a hashtag is on a video that is related to what they're talking about. They don't all fit in one monolithic idea. Some videos are pure just news content and some videos are much closer to propaganda or even misinformation, but you can't look at a hashtag and get the full sense of what everything is saying within that group of videos.

Micah Loewinger: Hashtags are a way for people who are making videos to have their content end up in front of other people on the platform. It's not uncommon to see a video that has a long list of hashtags. People are trying to kind of game the algorithm.

Drew Harwell: To complicate matters even further, when a hashtag does really well, people will just start adding it to totally unrelated videos to try and get some of that viral juice from TikTok. TikTok being this big mystery that doles out virality to people on random basis, just makes people do a lot of illogical things. Looking at a hashtag from afar and expecting that it tells you all about the politics of the people posting it, is not the best idea, but it's one of the few indicators. You've seen people really jump on hashtag data as their main way to understand this platform.

Micah Loewinger: But it is fair to question TikTok's algorithm, right? We've discussed on the show before, how the secrecy surrounding how social media sites share content can be problematic, right?

Drew Harwell: Yes, absolutely. Before TikTok, we had algorithmic anxiety about YouTube rabbit holes and Facebook and its effects on politics. I think that's just a reality of the conversations we have and our skepticism about these giant platforms with a big influence on how we get our information. But the thing about TikTok's algorithm, the China connection makes these conversations spin into conspiracy really quickly.

Micah Loewinger: Given what data we do have access to, how would we be able to determine whether say TikTok were putting its thumb on the scale and promoting #freePalestine over #standwithIsrael? Would there be a tell?

Drew Harwell: I think one tell would be that what TikTok is showing is dramatically different from the other social networks. The gap you see on TikTok where #freePalestine gets more views and is attached to more videos, is basically repeated on American social networks, including Facebook and Instagram. On Facebook, the #freePalestine is on more than 11 million posts, and that's basically 40 times as many have #standwithIsrael. Same thing on Instagram, pro-Palestine hashtags are on 6 million posts. That's 26 times more than the pro-Israel hashtag.

If there was a political sentiment that was going viral on TikTok that was not borne out by the Pew Research Survey, you would start to think like, "Okay, well then, why is TikTok deciding to show this information, this content to begin with?"

Micah Loewinger: You're referring to survey data from Pew Research that found that young people have, for some time now, been more pro-Palestinian than pro-Israeli in our country.

Drew Harwell: Yes. There was a Pew survey last year that found Americans under 30 were more favorable to the Palestinian people than people who are older than 30. Even the polls, since the war began, have shown that out. Is TikTok affecting how people feel about this war, especially young people? I think that's entirely reasonable and likely, but we don't see that it's doing this mass reversal of how young people feel about this conflict. If anything, it's reflecting what we already know.

Micah Loewinger: I want to turn to an anecdote of the ebb and flow of discussion on social media that got some press this week. We saw a slew of videos on the app responding to Osama bin Laden's letter to America that he wrote following the attacks on September 11th. He is asking his followers to live a life of purity, to reject immoral acts of fornication, homosexuality. He talks about how the United States has been taken over by Jews who control their economy, their media, all aspects of your life, making you their servants and achieving their aims at your expense.

TikTok clip: If you haven't read it yet, read it. However, be forewarned that this has left me very disillusioned.

TikTok clip: I will never look at life the same. I will never look at this country the same.

TikTok clip: Please come back here and just let me know what you think because I feel like I'm going through an existential crisis right now, and a lot of people are, so I just need someone else to be feeling this.

TikTok clip: Whew. It's a lot. It's a lot.

Micah Loewinger: Given how hateful large parts of this letter are, what revelations were people finding in it?

Drew Harwell: People were zooming in on the parts where bin Laden talks about the Palestinians, where he talks about the American people supporting the Israeli "occupation" of the Palestinian's land. That was the justification for killing 3,000 Americans and sowing terror around the world. They were extracting very small morsels and holding these up as, "Wow, maybe America was wrong," and yet people were not engaging with the fact that this was written after 3,000 Americans had been killed in a terrorist attack.

That was what was especially frustrating to people. People were sharing this letter as something that was a valuable critique of American foreign power and really, it's like sharing the Unabomber Manifesto. It really at its core is a very hateful document.

Micah Loewinger: There are multiple beats to the story that I think help explain why we're even talking about it. I think one reason was the letter that some TikTokers had been sending their followers to was hosted on The Guardian, the British outlet that had posted the letter in full shortly after it was written in 2002. But after news of these TikToks started to spread, The Guardian took down the Osama bin Laden letter. What happened?

Drew Harwell: This letter was written in Arabic, it was translated to English 20 years ago. It's been on The Guardian's website for a long time. It's on actually official US government websites, right? It is not hidden. Yet, everybody was going to this one link and The Guardian said, "Okay, well, we don't want to be hosting terrorist propaganda for people. We're going to pull this down and we're going to put in this place something that says document removed and we want to point people to the story where we talk about the context. We talked about it in a news environment."

Of course, it's not received that way. When TikTok users saw that the document was pulled, they said, "Okay, well, this is proof that actually the media machine is out to get us, that there's this piece of forbidden knowledge that we're no longer able to access." There's a researcher at the Stanford Internet Observatory named Renée DiResta, who's advised Congress on stuff like this. She said, "Don't turn the long public ravings of a terrorist into forbidden knowledge. Something people feel excited to go rediscover."

Let people see for themselves, like he may not have 100% evil points, he may make some fair points, but this guy is a murderer. You have the context to this person in this letter that some talkers would otherwise just glorify.

Micah Loewinger: To that point, there's like a little message now when you search Letter to America on TikTok, basically showing no videos when you type that in under the video search tab suggesting that they're now suppressing the search. Is that something that you've observed?

Drew Harwell: Yes, TikTok has been telling us that they're banning the video for support of terrorism, which is a rule that they've had for a long time. They're suppressing the hashtag. Whenever you search it, it goes to video not available. I've been watching through the day as these videos just disappear into the abyss. Facebook and Instagram did basically the same in the last 24 hours as well. TikTok's argument too has been that they're not just aggressively removing the videos. They're also, in their words, investigating how the videos got onto the platform in the first place.

They're also saying that the number of videos had been small, that it wasn't really trending on the platform. Then there was a viral thread on X formerly Twitter that has been viewed 20 million times and it had people seeking out these videos.

Micah Loewinger: This is the Streisand effect-

Drew Harwell: Yes, totally.

Micah Loewinger: -in full force, and this seems to be part of the problem or pattern with media coverage around TikTok, it's just fuel on the flames.

Drew Harwell: Yes, exactly. It's not to absolve TikTok, but the internet is a big food chain. This happens every time. Often, it'll be somebody who's media adjacent who will popularize something as this big TikTok trend that, "Oh my gosh, what is Gen Z doing now?" Really, it's like a micro trend if it is a trend at all. My observation of it on TikTok was it really wasn't that big. I counted maybe a couple of hundred videos, none of these videos were really going hyper-viral. TikTok's numbers are so inflated because it has 150 million users in the US.

People are flashing through videos like so many at a minute, so that a video with 1 million views, which a show with 1 million views on TV is a big deal, but a million views video on TikTok is really not that big deal. This was something that seemed fairly, I guess, mid-size, is the way I would put it, but after that thread on Twitter and it became this panic in a way, it really sent it into the stratosphere.

Micah Loewinger: I guess this brings me back to a theme of our conversation, which is the urge to exceptionalize TikTok. On the same day that discussions about the Osama bin Laden videos on TikTok were bubbling around the internet, Elon Musk, the owner of X, replied to an outrageously anti-Semitic white supremacist conspiracy post.

News clip Musk posted agreement with the false claim that Jewish communities have been pushing the exact kind of dialectical hatred against whites that they claim to want people to stop using against them.

Micah Loewinger: One of the richest men in the world has just attracted thousands and thousands of people to far-right white supremacy.

Drew Harwell: Yes. Twitter and TikTok are held at different standards. You have the issues that people ding TikTok for about their ownership and algorithms that promote content that we don't know how they work. I mean, you see those as problems everywhere, including on Twitter, where we know the owner has issues.

Micah Loewinger: What's the right way to feel about the future of TikTok? Is it a violent, disgusting cesspool that's turning us all into media-illiterate zombies? Is it a place that should be regulated? What do you think?

Drew Harwell: TikTok is a speech platform like a karaoke machine. It can be used for good and evil. You see a lot of alarming stuff on there. You see stuff go viral that you would never want your kids to see or anybody to see. That is true of a lot of social media websites, and why are we only talking about one ban of one app and no regulation for anybody else? I think that's where it starts to get a little unnerving. When we think about these issues, we should think about regulating them as issues. If we don't want people giving away their data and having it being used in ways they don't want, maybe we set a law for that covers every tech company.

If it's something about disinformation or propaganda, what if we have an algorithmic transparency law so we can know what goes viral why. That would cover not just the fun little video app, but also Elon Musk's app and Instagram. I think the right way to think about it is let's base our decisions and our policymaking on evidence, not speculation, not moral panics, and not act like all of these problems are focused on one little fun, happy, scrolling app and that if we ban it, they all disappear.

Micah Loewinger: Drew, thank you very much.

Drew Harwell: Thank you.

Micah Loewinger: Drew Harwell is a tech reporter for The Washington Post.

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, a final goodbye to the crusading feminist website, Jezebel.

Micah Loewinger: This is On the Media. This is On the Media, I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Jezebel is no more.

Initiated back in 2007 by Gawker Media founder, Nick Denton, he saw it as a way to serve Gawker's readers who were mostly female in the snarky style of Gawker's 13 other blogs. To its founding editor, Anna Holmes, who'd spent years toiling in the orchards of traditional women's magazines, Jezebel would serve as a counter to the artifice and fantasies of those magazines. As a community for a new and diverse generation of women who lived in the real world, the Jezebel of my imagination, and eventually my reality, she recalled in 2010, would serve as an antidote to the superficiality and irrelevance of women's media properties.

Their reliance on insecurity creation, misogyny, and unabashed consumerism had become increasingly offensive. Jezebel was groundbreaking, a smash hit that did precisely what Anna Holmes had hoped, but in 2010, she left. The website lived on, even after Gawker was bankrupted by Hulk Hogan's sex tape lawsuit. Remember that? Jezebel's plug was finally pulled by G/O Media this month. Holmes says that the site's crucial place in feminist lore wasn't a given at the start.

Anna Holmes: There was a meeting I remember very clearly when I was sitting outside the Gawker offices with one of my bosses and I had mentioned the F-word, feminism, and he cautioned me against it. In that moment, and I remember it very clearly, I thought, "Well, I'll show him." Because it made sense for the site to explore gender politics and racial politics because the Gawker Media websites tended to punch up. You had Gizmodo which was their technology blog and it tended to go after companies like Apple, Jalopnik, car blog would go after GM.

Gawker itself tended to critique mercilessly big media. It made sense to me that they would have a women's website that would punch up towards, let's say, women's magazines. The feminism angle, however, was something that was very specific to myself and the staff. That was not something that we were being asked to do, and as I said, in fact, we were being cautioned against it.

Brooke Gladstone: What did that mean? What were you being subversive about doing?

Anna Holmes: Well, the tagline of the site was, "Celebrity, sex, fashion without airbrushing." That's an acknowledgment that these topics of celebrity, sex, and fashion had been airbrushed in women's media. Because young women had been taught to privilege certain topics over others, celebrity, sex, or fashion, because those topics were the bread and butter of women's magazines and celebrity magazines. We wanted to take a different approach to those subjects by using them as entry points into discussions about gender politics and racial politics.

There have been examples in child-rearing books about hiding broccoli in a brownie. This was a way of hiding broccoli in a brownie, although there were times when we just served broccoli as well.

Brooke Gladstone: In terms of wrapping the broccoli in a brownie, one of your early exploits at Jezebel was to offer a $10,000 bounty for an un-airbrushed celebrity photograph which you actually got.

Anna Holmes: I don't know that that was my idea. I wish I could take credit for it but it might've been the idea of Nick Denton who was the owner of the company. He's the one who ponied up the money, the $10,000 bounty/reward. I probably had complained about the ways in which pictures were airbrushed. I know that he thought it would make a slash. I didn't actually believe though, that we were going to get sent a photo and then the photo came in of Faith Hill, photographed for the cover of Redbook, and it was unretouched. Maybe calling it a revelation is going too far but it was quite shocking what they had done to her photograph.

Brooke Gladstone: What did they do?

Anna Holmes: They smoothed out lines and curves, anywhere on her body or face that they could have. She looked a little bit like a human doll, the way that a lot of actresses and models had been made to look on the covers and in the interior pages of women's magazines. She didn't look like herself, particularly when compared to the original photograph. She was a very beautiful woman. We had become so used to seeing airbrushed photographs that I don't know that we could have looked at it without the original and honed in on what it was that had been done.

Brooke Gladstone: What was the subtext of that enterprise?

Anna Holmes: Well, the subtext or maybe even the overt text was that women's magazines and women's media, a lot of it was built on a lie. In that case, there was visual evidence of it but the critique extended to the stories, content, and headlines, et cetera, put forth by those magazines. We made critiquing women's magazines and industry in and of itself. Every day on that site, there was some critique, and that's putting it nicely.

Brooke Gladstone: For instance, you tracked the number of models of color in fashion brands and in women's magazines.

Anna Holmes: Our critique went from race to economic class to sexual identity. I think one way in which we failed is the way in which we didn't acknowledge growing conversations around gender identity. With regards to race, there was one writer, Dodai Stewart, who was one of the first staffers to be hired. She had many aspects to her job but one of them was that she went through women's magazines every month and also the photographs that came out of fashion shows and counted up the models of color that were on the runways and that were in the editorial pages of these fashion magazines.

She took them to task. She did this again and again and again. We would have readers who would comment. They were sick of hearing about it. They got the point. I really did believe and she believed that by repetition, we would get the point across more. We had no proof that by complaining about the lack of diversity on the fashion runways or in fashion magazines that anyone was actually going to pay attention besides the readers. You started to see at some point, it's hard for me to pinpoint things changing in women's magazines and on runways.

I do think that what Dodai was doing had an effect in terms of shaming fashion designers and magazines. The other thing is that we would write stories and they would get picked up elsewhere. It wasn't that everyone was reading Jezebel. It's that people who were in charge of creating content for other blogs and websites were reading Jezebel and commenting on the stories that we were posting. The internet was a little bit of a wild West on the one hand. On the other hand, we helped one another out. You saw this most acutely among websites that were much more explicitly feminist than ours was.

We used, as I call it, the F-word, quite liberally and unapologetically but I don't know that I would've described the site as a feminist blog. There are reasons for that, that I'm happy to get into if you want.

Brooke Gladstone: Sure.

Anna Holmes: Most of what I defined as feminist blogs were, unlike Jezebel, Labors of Love that were not being financially supported by a company. They were written and edited and published by young women who were not getting paid to do so, whose focus was explicitly on gender politics in a way that ours wasn't. We would post about a recap of the previous night's episode of Mad Men. That's maybe not a great example because Mad Men is full of gender politics commentary. It felt unfair to claim the mantle of a feminist blog.

Brooke Gladstone: Interesting mentioning Mad Men, there's another case where maybe broccoli was wrapped in a brownie. If you operated under the principle that if you repeated things enough, they'd start to sink in. You did deal with reproductive rights, racism, sexual harassment, and assault. They wouldn't feel like outliers in your magazine. You've said that there was once a reluctance to talk about subjects that related to women's lived experience.

Anna Holmes: Yes, and the idea that we had a publication where stories about, let's say, Mad Men coexisted along a story about diversity or lack thereof in the fashion industry, next to a story about reproductive rights and the ways in which they were being eroded. Women, as I like to say, can walk and chew gum at the same time, and they can be interested in all of those things and more. Again, the repetition was about normalizing a conversation. I can't give enough credit though to the readers. It was one thing for us to repeat ourselves.

It was another thing to offer a platform for tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of women to share their own stories and to be taken seriously, and to support one another. I do think that you can draw a line between the conversations that were happening on Jezebel and other blogs, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, et cetera, to the big reported revelations around powerful men and sexual assault that you started to see happening in 2017 and beyond.

Brooke Gladstone: How would you characterize Jezebel's commentators, the good, the bad, the ugly?

Anna Holmes: I have so many words to describe them. They were opinionated. They were loyal. They were sometimes bitchy. They were animated and vociferous, and they were complicated, and they were really hilarious a lot of the time. Very smart, impatient, they were critical. Within a few weeks of the site's launch, there were commenters who were calling themselves the Jezebels. It made me somewhat uncomfortable because of the quickness with which they took to it, and the kind of responsibility that I felt to them because of it.

They drove me crazy. They drove the writers crazy as well because of the fact that they were watching us so closely, so closely. There were times when it felt like it was us versus them.

Brooke Gladstone: You make them sound like a bunch of unruly collaborators, which to a great degree, I know they were but they also could be incredibly mean intellectually dishonest, bullies toward each other.

Anna Holmes: Yes, they were unruly, and they were all of those things. They could be bullying and they could be intellectually dishonest. We had to moderate the comments. As much as it sometimes felt from my point of view, like a free-for-all, it really wasn't. We could ban people and did. We didn't really delete comments. Nick Denton didn't want us to be deleting things. We had a certain function at one point called disemvoweling, the V, which meant that if there was a comment we didn't like, we would press a button and it would remove all the vowels from the words in the comment, which drove the commenters crazy.

Brooke Gladstone: Shortly after Buzzfeed News shut down, in a column for The New York Times, Ben Smith posited that, "If the end of BuzzFeed News which he created was the end of an era of digital news, Jezebel," he said, "was the beginning." He pointed to how the commentators on Jezebel, the community it created, responded to each other. You took issue with his portrayal of Jezebel as a blueprint for the outrage that would come to rule social media. Now, Jezebel's heyday was before social media, but he argued that the kind of freedom and the kind of anger that it manifested, I think that was his argument, opened the door to what technology would later usher in.

Anna Holmes: I mean, I just reject that. Well, first of all, I don't know exactly what his argument was. I tried to pin him down on that for The New Yorker piece that I wrote. I was confused by the piece that he wrote. It seemed to me that he was making an argument that Jezebel had an anger that was out of control. That we trafficked an outrage or expressed emotion or opinions in ways that felt somewhat unhinged. He used the phrase uncontrollable anger in his piece. I felt that was sexist.

I didn't like that he seemed to be suggesting that the divisive tenor of discourse online, particularly on social media, could be traced back to the site. There was plenty of discourse happening on the internet before Jezebel and during that was contentious. One could argue divisive, made one uncomfortable, et cetera. I wasn't quite sure why he was singling out Jezebel. I do think because he was not the target audience for the site, like most men weren't that there was a deep discomfort with the anger that was being expressed on the site because it was coming from women.

In his defense, when I called him out on the uncontrollable anger phrase, he conceded the point, which is that it sounded sexist. I made the point to him that women's anger is, in fact, usually very controlled because that's the ways in which we've been taught to express it. He was very complimentary about Jezebel in the book that he published this year called Traffic, which looked at a number of websites and website companies and the ways in which they rose and fell. That op-ed where he mentioned Jezebel's augering the beginning of a more contentious discourse online, didn't necessarily land the point.

I was confused by it, and I tried to ask him what he meant by that. He answered, but I think that he was probably struggling with, "Well, when does X start, and when does Y start in relation to X and was this all happening at the same time?" At the time when Jezebel launched, social media was not really a thing. I'm not saying it didn't exist, but it was not the thing that it is now. The sorts of commentary that one found on Jezebel or other websites, or in the comments of Jezebel and other websites, were very self-contained to those websites.

Once you get Twitter going, and they introduced the retweet button, which I believe happened in 2008, maybe even 2009 or '10, I'd have to go look it up, is when you start to see an explosion of online commentary that moves very quickly throughout the internet.

Brooke Gladstone: Virality.

Anna Holmes: Yes. That privileges more emotional language over other types of language. My rejection of Ben's argument also has lots to do with the fact that the site started before social media became ascendant. I don't know that I feel as defensive about it as I did when I first read that op-ed, but that's in part because I've had time to think about it. I wrote about it. I talked to him about it. That's one thing I think that we don't do enough of which is to engage our critics in good faith. I didn't take to Twitter to yell about it, which is maybe something I would have done years before.

I think that a lot of the discourse online is very performative. I don't think that that was the case with what was happening on Jezebel. I don't unlike Ben draw that straight line between the site and what social media later became. It would be giving the site too much credit, in a way to imbue it with that much power.

Brooke Gladstone: I'm a lot older than you. I'm a classic second-wave feminist, I guess, watching the various waves of feminism go by. I just wonder how you think Jezebel influenced the broader culture, especially with regard to feminism.

Anna Holmes: I remember when I think, this was in 2010, maybe 2011, Tina Fey's 30 Rock did a parody of the site.

Brooke Gladstone: What was it called?

Anna Holmes: It was called Joan of Snark.

Speaker 17: Wonderful news non-famouses. My publicist just called from rehab. I made the internet.

Liz: You're on JoanOfSnark.com.

Speaker 18: On what?

Liz: Joan of Snark. It's this really cool feminist website where women talk about how far we've come and which celebrities have the worst beach bodies. Ruth Bader Ginsberg.

Anna Holmes: As is the case with many parodies, it wasn't necessarily positive. The idea that a large powerful network TV show was good parody, our little site meant that it was having an effect on someone, it was making an impression on someone. I think that it's unapologetic embrace of feminist ideas. The repetition of the word itself, served as a model, especially for younger women, a comfort in our own skin with regards to our gender politics. You started to see actresses and celebrities being asked on red carpets, whether they consider themselves to be feminist. This was not happening before.

It did feel like there was an opening up in the culture around what feminism was, could be self-identifying with it. In 2014, Beyoncé performed in front of an enormous lighted sign that said, feminist and this was at the MTV Video Music Awards. I don't think that you would have seen that happen were it not for the influence of feminist discourse on the internet. I'm being very specific when I say the internet because that's where everybody was in 2014. That's where everybody is. Do I think that she would have done that in 2006? I don't mean to suggest that she was doing that cynically.

I think that, as time went on, all of our gender politics were evolving. I don't know whether she read Jezebel, and I don't know whether she read Feministing or any of the other feminist blogs that existed, but something got to her and she felt comfortable enough, claiming that word and the identity as her own. I do think it has to do with the Internet.

Brooke Gladstone: I love the way that you ended The New Yorker piece. You said you saw Jezebel not as the beginning of the end of the digital media era, but as a moment, a spark within an ongoing discussion about gender politics. Then you concluded with a quote from the late civil rights activist, poet, philosopher Audre Lorde, something she wrote way before the internet in 1981 that seemed to speak to Jezebel's legacy.

Anna Holmes: What I said at the end of that New Yorker article was that Jezebel and the conversations that it sparked have led to new realities around sexual assault, harassment, pay inequity, and cultural depictions of women. Those conversations also make people uncomfortable in part because they involve women expressing their anger in public and sustained ways. Then I went on to quote Audre Lorde, and I said, or rather she said, "Every woman has a well-stocked arsenal of anger, which can act as a powerful source of energy serving progress and change."

[MUSIC - Kronos Quartet: Tilliboyo]

Brooke Gladstone: With regard to Jezebel's legacy?

Anna Holmes: Well, I don't know that I'd say that its legacy is one of anger, but its legacy is one of providing a space for women to express themselves up to including beyond anger but including other things like humor, being able to express the full range of emotions that they have and the full range of people that they are.

Brooke Gladstone: Anna, thank you very much.

Anna Holmes: Thank you so much.

Brooke Gladstone: Jezebel's founding editor, Anna Holmes.

Micah Loewinger: That's it for this week's show. On the Media is produced by Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clark-Callender, and Candice Wang with help from Shaan Merchant.

Brooke Gladstone: Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: And I'm Micah Loewinger.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.