How Chinese State Media Covered The Biden-Xi Meeting

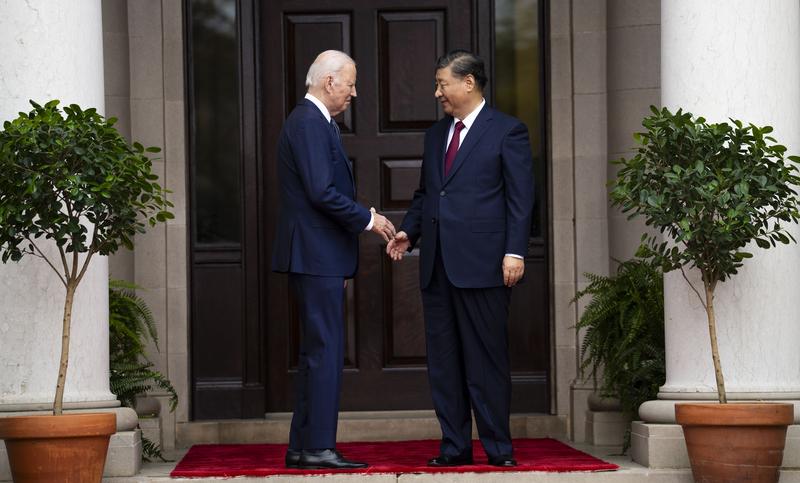

( Doug Mills / AP Photo )

Micah Loewinger: From WNYC New York, this is On the Media. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Earlier this week, presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping came together for a long-awaited meeting in Northern California. Some early coverage suggested that little was gained, but according to who?

News clip: President Biden is touting what he's calling important progress in US-China relations.

News clip: Will reestablish direct contact between our militaries and that China will help take steps to stop the flow of fentanyl into the US.

News clip: China's President Xi Jinping later gave a speech in San Francisco where he spoke positively about meeting President Biden. He also said his country has no intention of challenging the United States.

Daniel Sneider: The meeting really exceeded my expectation.

Brooke Gladstone: Daniel Sneider is a lecturer in East Asian studies and international policy at Stanford University.

Daniel Sneider: Because I think both men were determined to bring the relationship back from the brink of confrontation, avoid conflict, restore communication, both at the highest level, but all the way down through the government and beyond the government.

Brooke Gladstone: This reset was more than obvious in the state-controlled Chinese media. For example, ahead of the meeting, the state news agency, Xinhua ran a long piece in English about the enduring strength of Xi's affection for ordinary Americans with photos of him sitting in a tractor smiling with an Iowa farmer taken on a visit to America in 2012. In fact, some of the people Xi met on that visit were actually present at a dinner with him on Wednesday.

Daniel Sneider: It's an easy way to say, "Hey, I have been your friend. I want to be your friend." Chinese state media is very accomplished and used to doing what's necessary to signal what the Chinese government wants, and they pick up certain, very familiar themes, but also specific events that they've used before. The other one, which again, is not something unprecedented, it was this commemoration of the Flying Tigers, the American volunteer pilots who fought with the Chinese against the Japanese in World War II, even before the US entered the war.

Brooke Gladstone: That was in defense of Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang government, not the communist.

Daniel Sneider: Well, the Chinese Communist Party, when they want to, will take on the mantle of representing all of China, including acknowledging that the China, at that point, was not led by them, but led by the nationalists. They do that when they're looking at wartime history a lot because it also allows them to inherit and claim the place of China as a global leader because you remember during World War II, we had these pictures of Chiang Kai-shek, Roosevelt, and Churchill all together, leaders of the Allied nations fighting the Japanese. The Chinese Communist Party, when it's useful to them, they embrace that legacy of Chinese leadership.

Brooke Gladstone: Xinhua published a five-part series in Chinese on Getting China-US Relations Back on Track. There was a torrent of other articles, and also the press highlighted recent visits to China by the American Ballet Theatre and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Anything else jump out at you in terms of the coverage around or during this event? No photos, I assume, of anti-Chinese protestors in San Francisco.

Daniel Sneider: No. The Chinese coverage of the APEC summit itself, first of all, is meant to focus on Xi Jinping and how well-received he was, and that includes pictures of pro-Chinese demonstrators, which were probably all organized by the Chinese themselves, and no pictures of protestors. The welcoming that he received from the business community, all these things are meant to say Xi Jinping, great leader. He's the one who's setting the tone. Biden is a little bit more the supplicant, if you will, seeking better relation.

That's Chinese propaganda, but I think it's also the case that the Chinese are very clearly signaling, and they did it in their coverage, that they want American investment and trade to come back to China. Chinese are suffering from a serious economic slowdown, recovering from the effects of the COVID epidemic, and the restrictive measures the Chinese imposed, plus the technology war, which the United States has led to restrict the flow of high technology to China, and the efforts of American business and a multinational business to shift their dependence on China to other investment locations, like Vietnam and India.

The Chinese really are in a full-court press to reverse that for their own reasons.

Brooke Gladstone: He also met with a bunch of American CEOs, didn't he? Had dinner with them.

Daniel Sneider: This was a huge event, a whole flood of CEOs, everyone from Tim Cook of Apple to Elon Musk to bankers of various kinds, tech executives from Silicon Valley all marching up there. This was maybe not more important than their meeting with Biden, but close. The speech that Xi Jinping delivered at that meeting was all about, "We need to live together in the same universe. The world's big enough for all of us. We don't want decoupling." Frankly, the American business community are eager to reciprocate.

Brooke Gladstone: But the shift in coverage, who's it for? Some of it, as I mentioned, was in English. Most of it wasn't. Is it for the Chinese public?

Daniel Sneider: It's both. They were signaling to the Chinese population, "Okay, this is our policy. We're not responding to the pressure of the United States. We've made this determination that we need to improve relations. We're putting the pressure on the United States to do that."

Brooke Gladstone: Does he reckon that this may reassure some in the Chinese business community?

Daniel Sneider: Xi Jinping needs to reassure the Chinese people that economic prosperity is going to return. That's essential. Inside the Chinese leadership, there's clearly a healthy debate going on about some of the policy decisions that Xi Jinping has made, backing the Russians, cracking down on Chinese private sector companies that are global actors in the marketplace like Alibaba, things that people see as a retreat from the market reforms that drove China's engagement with the United States and with the West.

Brooke Gladstone: I want to draw a little bit on your historical memory here. These kinds of shifts, you've seen them before.

Daniel Sneider: We saw it when China launched into its reform and opening phase under Deng Xiaoping. China had gone through a long period of the culture revolution of seeing the West as the enemy, the United States as the enemy, and beginning, of course, with the opening by Kissinger and Nixon in the early 1970s, which was an abrupt shift at that time, but it's followed later on when Deng Xiaoping embraces the idea of the market as a driver of the Chinese economy. He makes a very famous visit to the United States. We have these pictures of Deng Xiaoping with a cowboy hat on.

All of these were meant to signal that, "No, we have decided to completely change the way we interact with the United States and the outside world." They've done this more than once, and they've retreated from that as well.

Brooke Gladstone: Let's switch gears and talk about how Western media have been covering the Biden-Xi meeting. I take it you've had some gripes.

Daniel Sneider: Well, we've got this narrative, particularly American media, that we have a relationship that's in free fall, and we're heading to war over Taiwan. There's a whole narrative of threat, of inevitable crisis, and of course, there's some truth to the sense that we are obviously in the midst of a deep confrontation, if you will, but therefore, what happens is you tend to miss these turns because it doesn't fit your narrative.

Brooke Gladstone: Can you give me an example of what you see as the problem in the coverage?

Daniel Sneider: The one that jolted me out of my chair after the Biden-Xi summit meeting was a headline in The New York Times that read, Biden-Xi Talks Lead to Little but a Promise to Keep Talking. The story basically said, "Well, nothing really was accomplished here," and this is this focus on, "Oh, what's the deliverable here? Let me see some concrete things that you've agreed to that really show that there's been some breakthrough in the relationship," when, in fact, of course, the meeting itself is the accomplishment when you have no communication at a senior level for a long time, like more than a year, it has a huge impact.

What both men wanted to do was to demonstrate their ability and their willingness to manage the relationship and to signal that to everyone else around the world. That signal doesn't get through very clearly when you have press coverage, which basically says, "Well, really nothing happened here." The other piece of this that really, I find troubling, is coverage of US-China relations particularly that comes out of the mainstream media, is very shaped by the domestic politics of United States. Everything is in terms of, "Can Biden really do anything? It'll cause problems in his re-election campaign."

It's all focused on Biden in a way that I think misses the point. Xi Jinping wanted this meeting more than Joe Biden did. The really interesting question is, why did Xi come to this meeting? What's going on in China that tells Xi that he needs to do this? The coverage of what's going on inside China is really patchy, and a lot of times, it's just not there. We don't even think about China as a place where they are competing interests, different elements of the Chinese leadership, which may have different views. Now, it's hard to get a hold of that, but it's there.

Brooke Gladstone: Those of us who are casual readers, really just pick up on the chest-thumping.

Daniel Sneider: It makes for good copy but I also see that the media is looking for it. They ask Biden these questions knowing perfectly well sometimes that he has a tendency to say things in a less than precise manner. I saw it during the time of this summit meeting here. At the end of his press conference, a reporter said, "Well, do you still think that Xi Jinping is a dictator?" Well, Biden had said that at one point, and in a typical fashion he said, "Well--"

President Joe Biden: Look, Xi is indeed a dictator in the sense that he's the guy who runs a country that's based on form of government totally different than ours.

Daniel Sneider: I mean, he tried to smooth it out a little bit, but of course, the immediate pickup was Biden calls Xi a dictator.

Brooke Gladstone: So what do you think the Western press should do first to cover the US-China relationship better?

Daniel Sneider: A little more historical context would be good. We tend to view every event as if it's happening for the first time. There's a long history of the US-China relationship. There's more continuity than there is discontinuity. Let's go back to the Tiananmen incident in 1989 when the Chinese murdered many, many hundreds of student protestors against the Chinese Communist Party and the US imposed deep sanctions against China. After all, Bill Clinton ran for the presidency in 1992 talking about the butchers of Beijing.

We've been in moments of serious crisis, we hit it again in the mid-'90s when the Chinese fired missiles to try and influence the elections in Taiwan and the US deployed two aircraft carrier battle groups to the Taiwan Straits. There have been many moments of crisis and we've had to manage those things. I think the big difference between now and then is that in the last 12 years or so since Xi Jinping came to power, Chinese have really begun to see themselves as a great power, asserted themselves as a great power in a way that makes that crisis management a lot more difficult.

There's friends of mine in Japan who said to me they think the two signal moments for the Chinese turn to see themselves as a much more powerful actor than they did before, was the 2008 financial crisis in the US, which really diminished the view of the United States as being the sort of success story economically that China had to follow, and the Beijing Olympics where China emerges in a different kind of way. We're dealing with a bigger, stronger, in some sense, more difficult China, but we have a long history of trying to manage this relationship, realizing our interests are not the same, but they're also overlapping.

I am hoping for a return of more reporters back into China, and this depends on the Chinese more than anybody else, to let people back in and open things back up because we need to see more reporting on the realities of what's going on inside China. That's not convenient for Chinese, but is necessary.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you very much, Dan.

Daniel Sneider: Thank you.

Brooke Gladstone: Daniel Sneider is a lecturer in East Asian studies and international policy at Stanford University.

Micah Loewinger: Coming up, can we really blame TikTok for tipping the scales of public opinion on the Middle East war?

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media.