Read All About It

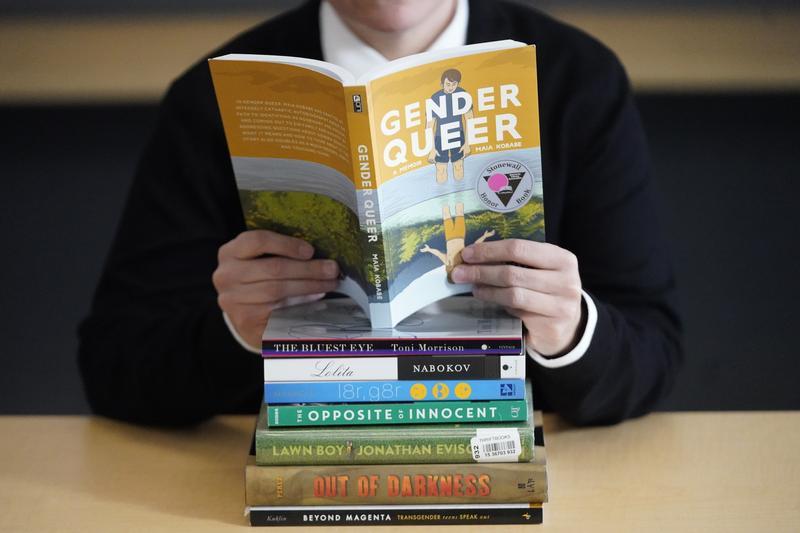

( Rick Bowmer / AP Photo )

Brooke Gladstone: This summer, the UN announced the era of global boiling has begun, but the damage of extreme heat can be hard to grasp.

Jake Bittle: The aftermath of a hurricane, you can see that there's thousands of homes that have been destroyed. The heat is more difficult. It's the deadliest climate disaster by a wide margin, but the deaths tend to happen out of the public view.

Brooke Gladstone: From WNYC in New York. This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. It's an old saying that journalism is the first draft of history, but when the historical record is too sparse to serve us, fiction steps in.

Toni Morrison: If a house burns down, it's gone, but the place, the picture of it stays, and not just in my rememory, but out there in the world.

Brooke Gladstone: Plus, a historian of slavery reckons with the gaps in the archives.

Tiya Miles: We could just throw our hands up and say, "We can't find what we need, so we can't tell these stories," but that would be an additional injustice on top of the historical injustices.

Brooke Gladstone: It's all coming up after this. From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. Across the globe, this summer has been unusually unseasonably and scarily hot.

News clip: This summer feels like a page torn from the book of Revelation.

News clip: Here in the United States, 170 million people are under heat alert. The world has entered the age of global boiling.

News clip: Climate scientists say it's virtually certain July 2023 will be Earth's hottest month on record.

News clip: This heatwave would've been virtually impossible if humans had not warmed the planet by burning fossil fuels.

Brooke Gladstone: Which means this summer will not be a one-off, and yet the danger of extreme heat can be hard to grasp until we're burned by it. In Arizona, the temperatures soared to 110 degrees for 31 days straight, transforming normal sidewalks into massive stovetops.

News clip: The pavement and sidewalk can heat up to 150 plus degrees, and that can cause second and third-degree burns if you're not careful.

Brooke Gladstone: Heat is called the silent killer because often victims are unaware of the severe damage their bodies undergo.

News clip: Officials say at least 1100 people have died in Spain and Portugal already as a result of the heat and fear the true death toll won't be known for weeks.

Brooke Gladstone: Meanwhile, in parts of Florida, the ocean might look as blue as ever, but the temperature is positively steamy.

News clip: The water temperatures are so high in the Florida Keys that they're endangering our precious coral reef.

News clip: The Florida Keys there on your map, registered 101.1 degrees this week. That is ideal temperatures for a hot tub.

Brooke Gladstone: Jake Bittle is a staff writer at Grist covering climate impact. He's written about the invisibility of extreme heat compared to other climate disasters and the challenge that presents to news outlets.

Jake Bittle: The aftermath of a hurricane, the news crews go to a place like Louisiana, and you can see that there's thousands of homes that have been destroyed and the power lines have busted and all that stuff. Heat is more difficult. It's the deadliest climate disaster by a wide margin, but the deaths tend to happen out of the public view, and so do the health crises that follow. Heat stroke cases are confined to the emergency room. Heat deaths tend to be people who are unhoused. It's not as eye-grabbing. I think for a long time it was excluded from coverage of climate change and natural disasters in general.

Brooke Gladstone: It's a visual issue and it's also a class issue because you can insulate yourself from it to a degree if you have air conditioning.

Jake Bittle: Yes, certainly. Hurricanes destroy the houses of the rich and the poor alike, but heat, all you have to do is turn on the air conditioner and you should be okay. It's people who lack air conditioning or they lack consistent access to housing. Also, migrant laborers, people who work outdoors, those are the people who end up getting sick and dying as a result of heat. You can avoid it for the most part if you're even moderately wealthy.

Brooke Gladstone: Does AC solve the problem?

Jake Bittle: In Maricopa County, which is the county that includes Phoenix and its suburbs, over 75% of indoor heat-related deaths over recent years have been the people who had air conditioning units. They don't always run the air conditioning because they can't afford the electric bill or it's broken and they can't afford to pay a contractor to come fix it. That's a big expense. The other thing that I think people don't understand is that heat exposure is cumulative. They continue overnight, and I think a lot of people, they think that they're okay because it's not extraordinarily hot, and so they turn off the air conditioner to save money while they're asleep and the body continues to break down.

Brooke Gladstone: I did not know that.

Jake Bittle: Yes, it's remarkable.

Brooke Gladstone: Extreme heat, as you say, it's hard to depict visually. The media instead are filled with a lot of clichés of stories about fried eggs on pavements, lots of crowded beaches.

Jake Bittle: Fire hydrants. They all seem so inappropriate. [laughs] The stories are about people getting rushed to emergency rooms. This is really scary stuff. A lot of major news outlets have gotten a little better at this. They'll at least send enterprise reporters or disaster reporters to the places where we know heat stress is going to be highest. The Washington Post has been pretty good about this. I just think the general machinery of natural disaster reporting just hasn't been set up to do this in the past.

Brooke Gladstone: It's getting better and the coverage is certainly more abundant. Then you have critics like Molly Taft in the New Republic who worry that the coverage seems to normalize this disaster. She cites a Media Matters analysis of coverage of an intense heat wave in Texas that found that only 5% of national TV news segments on it mentioned climate change.

Jake Bittle: This has been something that climate journalists have been talking about for a very long time. I think that a lot of major news outlets have gotten a lot better at that too. Then if you think about heat, a lot of people still perceive heat as weather. It's just the way that it feels today as opposed to a catastrophe that's bearing down on my city. What's the difference between heat and again, a hurricane or a wildfire, is that they're going to send out a science reporter or they're going to send out one of their field reporters to stand in the blustering winds or to interview people. With heat, it's going to be the guy standing in front of the chart and saying, "Look, it's 100 degrees." Those people don't traditionally make connections with climate change.

Brooke Gladstone: Here's the part of your article that really grabbed me. You observed that no president has ever made a disaster declaration over a heat wave that in theory, FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency can reimburse state and local governments for any disaster response that exceeds local resources, but in practice, it's never done so for a heat wave because heat disasters don't actually qualify as disasters.

Jake Bittle: Right. Yes. There's this law called the Stafford Act that governs what FEMA can and can't do. Heat is not listed as a disaster. There's a substantial debate about whether the fact that it's not listed means that FEMA can't declare a disaster. Certainly, the fact that it's not on there seems to have made it much less likely that they would do so. There's no precedent for declaring heat a disaster unless there's really no precedent for FEMA mobilizing all its resources to deal with a heat wave.

Brooke Gladstone: A major disaster is defined in that act as any natural catastrophe, including hurricane, tornado, high water, wind-driven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, mudslide, snowstorm, or drought, or regardless of cause, any fire, flood or explosion. Heat doesn't appear on the list, but heat kills more people than any other natural disaster, right?

Jake Bittle: Right. If you look at that list again, what is one thing that all those things have in common? They all destroy property or they destroy crops. They inflict significant economic damage to things that people own, and heat is the grand exception to that. There are certainly cases where heat will make crop yields lower, where heat will cause an expressway to crumble or something. For the most part, the economic damages are to human beings and human bodies and to labor output. Not the kind of thing that this act was set up to deal with.

Brooke Gladstone: This leads to the other fascinating observation you made that the media frequently take their cues from the government. If the government isn't acting as if it's a disaster, then it's not covered like it is.

Jake Bittle: Because a disaster like a flood is accompanied by a huge relief effort and they send the helicopters to pick people up out of the water and stuff like that, and because local governments traditionally send out huge alerts, if there's a hurricane coming in rural areas, often the sheriff will go door to door and say, "Get out of here."

Brooke Gladstone: It'll be on TV and radio for sure.

Jake Bittle: Right. There's a huge relationship between what the sheriff and the mayor are saying is a problem and what the media's going to say, and then what people will actually do. It's not a perfect relationship, but there is a huge downstream effect there that has long been missing for heat. It's not that I say that local governments don't communicate about heat, because I think a lot of them do very well, but historically, it wasn't something that emergency managers and local planners were really thinking that much about. That's changing very fast. You have to give people credit where credit's due, but if you look at the most famous example is the 1995 heat wave in Chicago, one of the deadliest heat disasters in US history or disasters, period, there was literally no plan.

Brooke Gladstone: You say that Portland and Seattle after some really horrible heat waves, now have heat plans.

Jake Bittle: I think that the Pacific Northwest is a really good example because like Chicago they really weren't prepared for a heat disaster of this kind and because of this exceptional nature of heat and the way that the federal government responds to disasters, they haven't received an extraordinary amount of money since that disaster to adapt to a future heat wave. What they've tried to do instead is, "Let's figure out how we can get better at public communication, and let's take the resources that we have and try to be better at the next one." For example, Seattle has so few air conditions spaces where they can create cooling centers, so they're trying to find more spaces where they can do that. Then, I think the hospital infrastructure was just not set up to deal with extreme heat.

For a heatstroke victim, the best thing you can do is just make the body as cold as possible as fast as possible. That often looks like dunking somebody in a tub full of ice, but there wasn't enough ice in Portland. Ice machines were in short supply. What this looks like is just making sure you stock up.

Brooke Gladstone: What about the problem of isolation? Is there a way to address that?

Jake Bittle: The fact that Americans are lonelier than ever, they live by themselves more than ever especially as they get older, is a huge problem for heat, because people tend to suffer in silence, so to speak. One thing that sociologists learned from the heatwave in Chicago is that communities where there was more social cohesion when people lived closer to their families tended to fare better than other communities at the same income level and with the same degree of access to air conditioning. Cities and community groups could dispatch people to knock on doors.

Brooke Gladstone: There was some of that during the early days of COVID.

Jake Bittle: That's true. They could also put out public communication saying, "Go check on your neighbors." I think that that's something that people are going to have to get a lot better. The question is, how do you make sure that those people know what the danger is and know where they can go?

Brooke Gladstone: What do you make of this push to name heatwaves like we name hurricanes? In Seville, Spain they tried to do it. This summer we've seen heatwaves Yago and Xenia. What's the point of that?

Jake Bittle: The idea of a named event I think is really powerful for a lot of people, especially in the United States in places that are vulnerable to Atlantic hurricanes. There's just this idea of it's a monster. It has a personality. It's malevolent as opposed to just being a distributed phenomenon of it's just hot outside. They focus-group this a lot to figure out what the best kind of name to give the heatwaves would be. I think at one point they were talking about spicy food for instance. That is like, "This is a scary thing. It's a defined thing with a beginning and an end, it's going to arrive and descend on your town." I think that they've found that it's decently effective in changing public perception.

Brooke Gladstone: I was wondering whether it enabled you to recall events and distinguish them like we remember Hurricane Sandy, or back in '92, Hurricane Andrew, or Hurricane Maria in 2017. We know where we were, what was happening, and how people suffered.

Jake Bittle: Absolutely right. In a place like Phoenix, for instance, you could imagine somebody in a year or two trying to think back on this summer, and they would just, "I think it was really hot out for a very long period of time," but they don't have like, "Oh, that one was Zoe or James or whatever," to distinguish it from something else.

Brooke Gladstone: An American meteorologist named Guy Walton, is trying to name heatwaves after oil companies like the BP Heatwave.

Jake Bittle: It's a clever statement, because many of these heatwaves, there's scientific evidence as I said that it certainly would have been impossible for them to be as bad as they are even if they maybe would have happened under the same circumstances. While you can't tie an individual heatwave to an individual oil company, you can tie the combustion of oil to heatwaves. Beyond heat being a deadly disaster, that's something the public really hasn't grasped yet and may not grasp for a while.

Brooke Gladstone: Jake, thank you very much.

Jake Bittle: Thank you so much for having me.

Brooke Gladstone: Jake Bittle is the author of Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration. You can find more of his heat coverage on Grist's Record High newsletter. Coming up, a couple of our obsessions, history, and books and how history books have become the genre de jeu. This is On The Media.

Brooke Gladstone: This is On The Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. 50 years ago if you wanted to be considered a serious novelist, you might write a contemporary novel, one that captured the current moment with all its anxieties and technologies. In the 21st century, the historical novel would give you far better odds for a critical hit. Take it from Alexander Manshel, author of the forthcoming book, Writing Backwards: Historical Fiction and the Reshaping of the American Canon.

Alexander Manshel: Between 2000 and 2020, something like three-quarters of the novels shortlisted for the National Book Award, the Pulitzer Prize, and the National Book Critics Circle Award took place in the historical past.

Brooke Gladstone: The New York Times Sunday Book Review section has a regular dedicated column for the genre, and at universities, the newer books taught are more likely to be set in the past, but as a reader, you may not have even noticed the growing infatuation with history in literature.

Alexander Manshel: Because the historical novel has become such a diversely practiced form by such a wide array of writers, it's almost become invisible to us as a genre in itself.

Brooke Gladstone: Consider the recent winners of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, two-time recipient Colson Whitehead set the Nickel Boys and an abusive reform school in the '60s.

Audio book clip: Some years you felt strong enough to head down that cement walkway knowing that it led to one of your bad places and some years you didn't. Avoid a building or stare it in the face, depending on your reserves that morning.

Brooke Gladstone: Meanwhile, Viet Cong win introduced readers to an ambivalent communist sleeper agent in '70s Vietnam with his debut, The Sympathizer.

Audio book clip: I'm not some misunderstood mutant from a comic book or horror movie, although some have treated me as such. I'm simply able to see any issue from both sides.

Brooke Gladstone: Louise Erdrich, 2021 winner The Night Watchman dropped audiences into a fraught moment on the Turtle Mountain Reservation in the mid-20th century.

Audio book clip: "Something is coming in the government," said Thomas, "They have a new plan. They always have a new plan," said Biboon. "This one takes away the treaties," said Thomas. "For all the Indians or just us," said Biboon. "All."

Brooke Gladstone: These books, different as they are, do more than transport us to another time and focusing on lesser-known histories, they ask us to consider what's worth remembering at all. In a piece that first ran in March, On The Media producer, Eloise Blondiau chatted how his historical fiction became a rich resource for reckoning with our past.

Eloise Blondiau: Last year, Hilary Mantel, the historical novelist, died aged 70. In her memory, a lecture she gave for the BBC was recirculated.

Hilary Mantel: History is not the past. It's the method we've evolved of organizing our ignorance of the past.

Eloise Blondiau: History, Mantel says, is the record of what's left on the record. It's what's left in the sieve when the centuries have run through it.

Hilary Mantel: It's no more than the best we can do, and often it falls short of that.

Eloise Blondiau: At On The Media, we often examine the failings of our historical record, and many historical novelists have long engaged in the same project, to bring the dead back to life.

Hilary Mantel: I promoted you, I am responsible for your rise.

Eloise Blondiau: In her Wolf Hall trilogy, Mantel resurrected Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII. In the BBC's faithful adaptation, Boleyn confronts the King's advisor, Cromwell, who would plot her execution.

Anne Boleyn: At the first opportunity you've betrayed me. Those who've been made can be unmade.

Cromwell: I entirely agree.

Eloise Blondiau: Mantel's Boleyn is brave and erasable. She uses the little written evidence we have to tell us who Boleyn was, like a letter that told of Boleyn describing her imminent beheading defiantly.

Anne Boleyn: I only have a little neck, so it'll be the work of a moment.

Eloise Blondiau: Mantel received pretty much every accolade a novelist can hope to win, but that almost didn't happen. When she first tried to get published, she ran up against the shabby reputation of historical fiction.

Alexander Manshel: Quite famously, Henry James wrote in a letter to a friend that the historical novel was, "Tainted by a fatal cheapness."

Eloise Blondiau: Alexander Manshel is a professor of literature at McGill University, and he's also my guide.

Alexander Manshel: The idea was that to actually access the historical past through fiction was an impossible task. The only people foolish enough to attempt it were those looking to make a quick buck on cheap thrills.

Eloise Blondiau: That doesn't mean it wasn't popular. Over the last century, millions of copies were sold. Think of Margaret Mitchell in the '30s, James Michener in the '60s and James Kloval and Ken Follett beginning in the '70s. That decade also saw the rise of these really funny sci-fi takes on the genre from authors like Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, and Ishmael Reed.

Alexander Manshel: Here are the example I think of. First, is Ishmael Reed's 1976 novel Flight to Canada, in which runaway slaves literally take flight aboard Air Canada Jet liners heading north, and Abraham Lincoln is assassinated live on satellite television. It's an absolutely wild novel.

Eloise Blondiau: Overall historical novels were considered more popular than prestigious, which might explain Mantel's challenges early in her career.

Alexander Chee: When she hoped to debut with a 700-page novel about the French Revolution, publishers were absolutely against it.

Eloise Blondiau: The writer, Alexander Chee, wrote about Mantel's experience for the New Republic. You quote Mantel saying they didn't want another novel about high hair.

Alexander Chee: Yes. [chuckles] Not realizing, of course, that she would go on to become world-famous and a bestseller for her Wolf Hall novels.

Eloise Blondiau: Of course, Mantel got her historical fiction printed in the end, but it was only after she first had a successful contemporary novel published. For Chee, who began his writing career in the late 90s, the opposite was true. It took him two years to sell his contemporary novel, Edinburgh. During that process, he had an idea for a very different historical book. He had been reading something that offhandedly described an intriguing woman.

Alexander Chee: She was a favorite courtesan of the emperor Napoleon III. She loved to walk on her hands because she'd been an acrobat and ride horses bareback. I thought, wait a second, what happened to her?

Eloise Blondiau: He sent his agent a note about a book that he'd later call The Queen of the Night.

Alexander Chee: That was the one that they overwhelmingly wanted. Editor after editor kept saying, "Can he do that one first?"

Eloise Blondiau: You write, "It was five years later that I was ready to sell a second book, and that little paragraph of a historical novel sold in nine days."

Alexander Chee: Yes, it was incredibly peculiar. I should say I was paid over 10 times for my second historical novel what I was paid for my first novel.

Eloise Blondiau: Between 2000 and 2010 when Chee's book was picked up, Alexander Manshel found that 80% of the novels that were shortlisted for major American literary awards were set in the past. Like Mantel's Wolf Hall, Michael Chabon's, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, which was set in World War II, and Ian McEwan's own war novel, Atonement.

Cecilia: Robbie, didn't you read my letters? Had I been allowed to visit you, had they let me, every day, I would have been there every day.

Robbie: Yes, but if all we have rests on a few moments in a library three and a half years ago then I am not sure.

Eloise Blondiau: Accolades were plentiful for the 2005 novel March, which Geraldine Brooks wrote about the father of the girls of Little Women. They also loved Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie's, Half of a Yellow Sun about the Nigerian Civil War. Why the about-face? Manshel notes that some novelists vying for highbrow prizes didn't want to date their work with tech that would seem old in just a few years.

Alexander Manshel: If you are a literary novelist, you are interested in having your work not only be read right now but having it last, having it survive to be read in the future. When writers set their work in the historical past, they're also in a way claiming a timelessness.

Eloise Blondiau: While the promise of eternal relevance may have tempted some writers to try the genre, that doesn't quite account for the scale of historical fiction's dominance today. According to Manshel, there's one pioneer of historical novels who often gets overlooked. When he tells people about his research, he's met with a common refrain.

Alexander Manshel: People will say, "Oh, you mean like Hilary Mantel?" When I say, "No, I mean like Toni Morrison," there's this brief moment of pause. When we think about what the historical novel is and does and what it should do, we think about the courtly drama of Cromwell and Henry VIII. We're not thinking about a woman in Ohio in 1873.

Eloise Blondiau: While Mantel's most celebrated books focused on the giants of 16th-century England, Morrison's work exemplifies the expansion of the genre in a different direction in America. The retrieval of otherwise disregarded histories, often by writers of color.

Manshel: Morrison in her most iconic work, Beloved, coins the term rememory. This is the idea that history lives on in the present, even for those who haven't experienced it directly.

Eloise Blondiau: Beloved won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1988, and it was a finalist for the National Book Award. It's often described as a ghost story about how a mother is haunted after she killed her own baby to keep her from being raised in slavery.

Toni Morrison: Some things you forget, other things you never do.

Eloise Blondiau: This is Morrison reading from Beloved.

Toni Morrison: Places, places are still there. If a house burns down, it's gone, but the place, the picture of it stays, and not just in my rememory, but out there in the world.

Alexander Manshel: This idea that there are histories, especially traumatic histories for marginalized people in the United States that live on in the present was central to Morrison's entire body of work.

Eloise Blondiau: In the 80s and 90s, Morrison's success was accompanied by a shift in the institutions that recognized American novelists, universities, publishers, and award committees. They were admitting more people of color than they had before and recognizing more marginalized writers in turn.

Alexander Manshel: At the end of the 20th century, as more and more Black, Asian American, Latinx, Indigenous, and Jewish novelists were finally being recognized by the literary establishment, the vast majority of the work that was being celebrated was historical fiction.

Eloise Blondiau: Those authors, Manshel says, were popular in universities because they allowed professors to both teach great works of literature and introduce students to history they may not have encountered before. Between 1980 and 2010, over 90% of the novels by writers of color that were shortlisted for a major American literary prize were historical.

Manshel: I'm thinking here of writers like Toni Morrison, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Alice Walker. It's about lesser-known figures and lesser-known histories, and that's actually part of the project.

Eloise Blondiau: In the past decade or so, a new class of writers has carried forward this tradition of disrupting the prevailing historical narratives. Like Morrison, Colson Whitehead weaves fantasy into his books. He transforms the underground railroad route that enslaved people used to escape to freedom into a literal subway system.

Audio book clip: Are we going down there?

Audio book clip: Yes, indeed. Mind this water now.

Audio book clip: After you.

Eloise Blondiau: In that book, Whitehead critiques the idea of linear, historical progress. His protagonist, Cora, escapes slavery only to find work in a museum as a performer in slavery reenactments. In this clip from the Amazon Show, Cora fearfully watches white men practicing their role.

TV show clip: You see, let it flow. If you like, you could add some dialogue. You know why? Stupid animal. How you like that?

TV show clip: Oh, you've done this before I take it?

TV show clip: Ah, well, that was a lifetime ago. [laughs]

Eloise Blondiau: Several recent prize winners follow families across generations. In her 2016 debut, Homegoing, Yaa Gyasi charts the lineage of two sisters over 300 years. Beginning in 18th century Ghana, one sister is enslaved and taken to America while the other remains in Africa. In 2017, Pachinko by Min Jin Lee follows the journey of one family over eight decades, beginning with a young girl in Korea who moves to Japan, where her family is mistreated. The stories of these ordinary Koreans falling in love, struggling to pay their bills, amid the giant storylines of war and mass migration, were not ones that Lee had encountered as a history major in college.

Min Jin Lee: It was so clear to me that everybody that I cared about, all the people that I really valued, all these lives, important lives to me, were not included in history. I thought it's something that seemed quite untruthful.

Eloise Blondiau: The first line of Pachinko is, "History has failed us, but no matter."

Min Jin Lee: The more important statement, I believe, is the subordinate clause of the statement, "History has failed us, but no matter," because it is a statement of defiance. I'm saying it doesn't matter because we are history, and we will be included, and we will persist anyway.

Eloise Blondiau: With Pachinko in particular, you're also tapping into a collective grief for generations past. I wonder if you write as a way to contend with loss.

Min Jin Lee: Yes. I think that every honest storyteller is really experiencing a kind of loss. It could be of life, it could be of love, it could be of status, it could be of money, it could be of friendship, it could be of community, it could be of nation. Some things cannot be had again. If we lose a parent or a sibling or a lover to death, we cannot get that person again. I think that it's honest to say that I rail against death because we have the time that those who have died do not have.

Eloise Blondiau: For Lee, writing novels about the past is a way to shape the future.

Min Jin Lee: You and I are making history right now, Eloise. It's breathtaking when you think of it that way, that 50 years from now, most likely I'll be dead. Let's say someone was considering, "Well, what did people in 2023 think about historical novels?" perhaps our conversation would come up and then we are making history. With that knowledge, I feel concerned about the value and significance of you and me talking about this.

Eloise Blondiau: That feels like more pressure. [laughs]

Min Jin Lee: Maybe it is. I guess I think of it as what an extraordinary thing that we get to be included.

Toni Morrison: The past, I suspect's probably more infinite than the future.

Eloise Blondiau: Here's Toni Morrison again.

Toni Morrison: The point is that there are lessons to be learned there so that we don't have to do that again. There's garbage in it also that you can throw out. It's all information. It's all the way we were. It's all part of who we are.

Eloise Blondiau: History has never been just the purview of historians as powerful as they are. The more we all add to the record of our history, the truer it will be. No matter if those contributions are merely bits and pieces, tatted cloth, names on park benches, old maps, or pottery shards. Add the alchemy of the imagination and you have a novel, a gateway to our common humanity in every era. For On the Media, I'm Eloise Blondiau.

Brooke Gladstone: Thanks again to Alexander Manshel, who shared with us so much research from his forthcoming book, Writing Backwards; Historical Fiction, and the Reshaping of the American Cannon. It's available for pre-order from bookshop.org or wherever you get your books. Coming up, Three Lives in Four Objects. This is On the Media. This Is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. We know history is written by the victors and that the gaps in the record mostly relate to the powerless. About them, there may be little left to find. The evidence has been lost to time. What then? You make do with scraps and shreds like a tattered seed sack from a little girl who was enslaved, found over a century and a half later embroidered with colorful thread. That's what historian Tiya Miles decided to do when she first saw it displayed. She read the inscription for me when we spoke earlier this year,

Tiya Miles: "My great-grandmother, Rose, mother of Ashley, gave her the sack when she was sold at age nine in South Carolina. It held a tattered dress, three handfuls of pecans, a braid of Rose's hair, told her, 'It'd be filled with my love, always.' She never saw her again. Ashley is my grandmother, Ruth Middleton, 1921"

Brooke Gladstone: Miles is the Michael Garvey professor of history at Harvard University and Radcliffe alumni professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Two years ago, her book called All That She Carried, the story of Ashley's sack, a Black family Keepsake, won the National Book Award and 10 other prizes. During her research, she learned that when the sack was first displayed, so many viewers cried that the curators handed out tissues beside it. Miles had often come across instruments of torture in her work, shackles, neck braces, but this sack opened a window into a profound and universal love emanating still from Ashley's sack.

Tiya Miles: I am an academic and I spend a lot of time in my head, but when I saw this artifact, I was completely overcome and overwhelmed. The object itself reflects not only the story of this family and the story of African American women who were enslaved but also the critical importance of affection, of care, of kinship ties to enslaved people.

Brooke Gladstone: You looked through Slaveholding records to find a record of an Ashley and a Rose together in a particular location, and you found that they were likely under the ownership of a man named Robert Martin.

Tiya Miles: The more I dug into the materials, the clearer it became that while Rose was a very common name for enslaved women in this place, Ashley was a very, very rare name. Ashley tended to be a name reserved for the English gentry. If I could find one of these rare Ashleys in the same set of records with a Rose, these were likely to be the daughter and mother pair I was looking for in the right time, the right place, in the same set of publicly available South Carolina documents.

Brooke Gladstone: With regard to Ruth, who embroidered the sack of her grandmother, it was easier to uncover her likely identity because there were more written records. She was married and pregnant at 16. She moved from the South to Philadelphia around 1920 and eventually became a regular feature in the Black Society pages.

Tiya Miles: Yes, Ruth is a fascinating figure in this history. She is someone who came from this family of Rose and Ashley who had experienced the worst that we could imagine as parents today. Yet Ruth was born free in South Carolina and decided to change her life, moved to the north as many African Americans were doing in this first wave of the Great Migration, and in Philadelphia, she became a young mother, and it was around this time that she had her first child, the girl named Dorothy, that Ruth Middleton started stitching this story of her foremothers on the sack that she still had.

Brooke Gladstone: Now, you initially set out to get answers, maybe even write the biographies of Rose and Ashley and Ruth, but you found unbridgeable gaps in the historical record. As a historian, what drove you to continue and how did your research goals change?

Tiya Miles: In the beginning, Brooke, I felt confident that I could do it. I would be able to trace these women in the South Carolina records. It turned out that they are very difficult to trace with certainty, and that is the case with most enslaved people who didn't go on to do something that made them famous, such as Harriet Tubman or Frederick Douglass. These were women who lived their lives out in slavery. They were not freed until the Civil War, never had the opportunity to learn how to read or write, they never escaped. It's much more difficult to identify them and to learn about the textured details of their lives.

Brooke Gladstone: In the paucity of information about Rose and Ashley, you still embarked on a history, but you wrote not a traditional history. It leans toward evocation rather than argumentation and is rather more meditation than monograph. You name several scholars as inspirations. One is Saidiya Hartman, a professor at Columbia University who coined the term critical fabulation to fill the blanks. If you can't tell their particular history, you can tell the history of people in similar circumstances about which there may be information. You can tell the history of their time, which is documented and transparently make a case that this is possibly what they experienced or what they felt.

Tiya Miles: Hartman introduces a method that really compels us to use our imaginations to fill in those gaps because gaps are all over the historical record when it comes to enslaved people, Black people, Indigenous people, women. Then we could just throw our hands up and say, "Oh, well, we can't find what we need, so we can't tell these stories." That would be an additional injustice on top of the historical injustices.

Brooke Gladstone: Let's talk about the contents of the sack. What Rose might have been thinking of when she packed it. For example, Rose included three handfuls of pecans. That type of nut was unusual for the mid-1800. I learned from your book.

Tiya Miles: Yes. I thought that pecans were native to the southeast because whenever I've gone down to the southeast, I've seen pecans everywhere. [laughs] I first imagined her going out to a pecan grove and collecting the nuts from the ground, but it turned out pecans, they're native to places like Texas, Louisiana, even Mexico, and they would have been imported by elites as a delicacy in Charleston at the time when Rose was enslaved there, which meant she certainly would have known how prized these nuts were. She may even have known how nutritious they were. In learning this information about pecans, I arrived at a conclusion which made sense when put together with other bits of information that Rose was probably a cook in the household of Robert Martin and his wife, Millbury Serena Martin

Brooke Gladstone: Of whom you paint a pretty persuasive portrait. These were people who were not old money, they were new money, and who were eager to impress by offering exotic things like pecans.

Tiya Miles: Yes. Robert Martin started off as a grocer, worked his way up to being something like an accountant to old money Charlestonian elites, and then he was able to acquire Black people, which increased his status dramatically.

Brooke Gladstone: How do you picture Rose getting her hands on three handfuls of pecans?

Tiya Miles: I have thought about this. I have wondered how was she able to get so many, and it seems to me that the timing of the packing of the sack mattered. Robert Martin died in the winter of 1852, not long after Christmas. I think it's very likely that Rose would have had pecans in the kitchen because they were used for holiday dishes. She may have had more pecans than usual at this time. She would have known when he died, and she may have suspected that this meant every single enslaved person in that household and on other Martin properties was now under the threat of being sold. She may have started to set aside some of those pecans. We don't know what she was thinking, Brooke. Maybe Rose was thinking that she would pack the sack for herself and for Ashley, and they would run away together, that she had escape plans in mind, but the majority of enslaved people could not escape, especially those who were in the deep South, like South Carolina.

Brooke Gladstone: Talk to me about the dress. As you go through the clues in Ruth's embroidery, one of the words is tattered. It was a tattered dress. What did tattered signify?

Tiya Miles: At the time that I was working on the book, tattered signified to me an item that was worn, perhaps torn, frayed, used, but as I have been sharing information about Rose and Ashley and Ruth and the sack, this reader told me that tattered may have been a way of saying tatted, and that tatted or tatting is a way of making fancy lace. Now I have these two interpretations, which I think are equally arresting. One of a worn and frayed dress, and one of a very special dress with fancy lacing, either of which would've been very significant to Rose and her daughter.

Brooke Gladstone: There were the pecans, there was the dress, and then, very fertile ground for your meditative approach, there was a braid of Rose's hair because while the facts of their lives were sparse, the tradition of hair as a means of connection was long and rich. What did your research suggest about the inclusion of Rose's braid?

Tiya Miles: We know that enslaved people had very little opportunity to care for themselves, to take care of their needs for hygiene, and yet in acts of resistance, they cared for their own selves and others. One of the major ways they did this was by doing hair. They might braid their hair, cornrow their hair, twine their hair with a string or with a piece of vine. They would do the same for others in their community, for loved ones, expressing love and dignity. Rose's hair would've been important in this way as a gift to Ashley in that it could be a reminder of caring for oneself and of caring for others through the physical act of tending and adorning the body. This braid that Rose packed would also have been a very tactile way that Ashley could have part of her mother with her, even as they were separated for the rest of their lives.

As I thought about this braid, Brooke, I also imagined the scene where Rose was freeing this braid from her own body to give to her daughter. I thought about what a radical act that was because, in the system in which she was captured in the view of her enslavers, Rose's body belonged to the Martins. They were the ones who had the right to it. By cutting her hair, Rose was asserting without words that no, her body belonged to her, and she was choosing to share it with her daughter as an expression of love.

Brooke Gladstone: You quote Laurel Thatcher Ulrich on what she calls the mananic power of things. Things become the bearers of memory and information, especially when they're enhanced by stories that expand their capacity to carry meaning. Could you tell me about the quilt made by your great aunt, Margaret?

Tiya Miles: I've grown up hearing the story of that quilt and getting a chance to take a peek of that quilts which my grandmother kept stored and protected in her closet. I always knew that the quilt was made by my grandmother's sister, by my great-aunt, and that this sister had been something of a hero in my grandmother's life because when my grandmother and her family were living in Mississippi in the early 20th century, they experienced a terrible, traumatic event, forced off their land by white men who had guns. My great-grandfather was forced to sign a piece of paper he couldn't read. He signed with an X.

This paper was some kind of property transfer, which meant that he was losing the land on which they lived.

My grandmother told the story to me and my cousins growing up, and she always talked about how at the time when the family was being expelled from their home, her big sister Margaret did something amazing. Margaret went out the back door of the farmhouse and she grabbed one of their cows. She took it over to a neighbor's home, which meant that even though the family lost almost everything during that expulsion, they still had that one cow due to the quick thinking and the bravery of my great aunt, Margaret. My grandmother was a young child during this incident, and Margaret was only a teenager. As I tell you this story, Brooke, I am actually looking at the quilt that Margaret made because I inherited it. It hangs on my wall right now. Whenever I see this textile, I think of Margaret's bravery, of the possibility for resistance and resilience, even in the worst circumstances that has been proven over and over again in the history of African-American women.

Brooke Gladstone: In addition to being a historian, you're a writer of historical fiction, and you've said that for every historical work you've written, you're drafting a couple of novels in the back of your mind. Can you give me an example?

Tiya Miles: Yes. Well, I can't help it because, as our whole conversation has shown, historical work is very important and I'm committed to it, but it is limited because we just can never fully reproduce the past and no historical source can reveal in a whole and deep way the interior experiences of people who lived in the past. The place for that is fiction. It won't surprise you to hear that Toni Morrison is one of my favorite authors, not just for her fiction, but also for her theory. I write fiction because, while I am thoroughly dedicated to reconstructing histories, I want to be able to say more, to move into that interior space, to open the doors that historical records always leave slammed shut in front of me.

Brooke Gladstone: You mentioned Tony Morrison. You say that Beloved is a book in which love and horror are intimately connected, that she uses the notion of haunting ghostliness, horror, to tell a story about love. I immediately thought of the historical work I'd just been reading, All That She Carried, horror and love intimately connected.

Tiya Miles: The artifact of Ashley's sack is an artifact of trauma and sorrow and separation and yet, the sack itself, the way that it's been received across time, the way that its holes have been patched so lovingly, its story inscribed on the fabric with care and attention tells us this is not just a trauma story. This is not even mainly a trauma story. This is a story of love, of perseverance, of resilience, of survival. If not for those attributes, Ruth Middleton would not have existed to stitch this narrative onto the sack. When she does preserve that story for herself, for her daughter, and for all of us now that we have the opportunity to review it and reflect on it, Ruth centers the word love. She highlights love, and she's telling us, I think, through that artistic decision, that this powerful emotion of affection and care and selflessness is key to her family's survival and perhaps to our own.

Brooke Gladstone: Tiya, thank you so much.

Tiya Miles: Thank you, Brooke.

Brooke Gladstone: Dr. Tiya Miles is the author of All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley's Sack, a Black Family Keepsake. Her novel, The Cherokee Rose, inspired by her research on a plantation, came out in paperback in June.

[music]

That's our show. On the Media is produced by Micah Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clark-Calendar, Candace Wang, and Suzanne Gaber with help from Shaan Merchant. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Andrew Nerviano and Sham Sundra. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On The Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.