How the Historical Novel Took Over

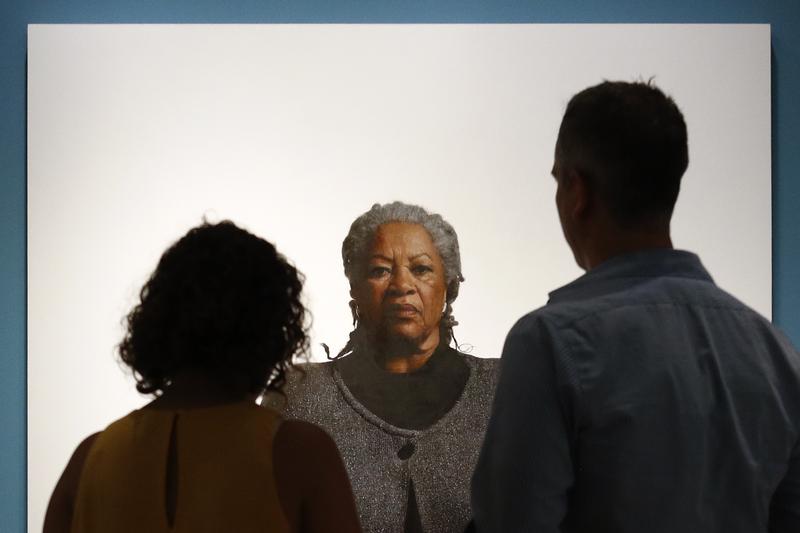

( Patrick Semansky / AP Photo )

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: This is On The Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. 50 years ago if you wanted to be considered a serious novelist, you might write a contemporary novel, one that captured the current moment with all its anxieties and technologies. But, in the 21st century, the historical novel would give you far better odds for a critical hit. Take it from Alexander Manshel, author of the forthcoming book, Writing Backwards: Historical Fiction and the Reshaping of the American Canon.

Alexander Manshel: Between 2000 and 2020, something like three-quarters of the novels shortlisted for the National Book Award, the Pulitzer Prize, and the National Book Critics Circle Award took place in the historical past.

Brooke Gladstone: The New York Times Sunday Book Review section has a regular dedicated column for the genre, and at universities, the newer books taught are more likely to be set in the past, but as a reader, you may not have even noticed the growing infatuation with history in literature.

Alexander Manshel: Because the historical novel has become such a diversely practiced form by such a wide array of writers, it's almost become invisible to us as a genre in itself.

Brooke Gladstone: Consider the recent winners of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, two-time recipient Colson Whitehead set the Nickel Boys and an abusive reform school in the '60s.

Audio book clip: Some years you felt strong enough to head down that cement walkway knowing that it led to one of your bad places and some years you didn't. Avoid a building or stare it in the face, depending on your reserves that morning.

Brooke Gladstone: Meanwhile, Viet Thanh Nguyen introduced readers to an ambivalent communist sleeper agent in '70s Vietnam with his debut, The Sympathizer.

Audio book clip: I'm not some misunderstood mutant from a comic book or horror movie, although some have treated me as such. I'm simply able to see any issue from both sides.

Brooke Gladstone: And Louise Erdrich, 2021 winner The Night Watchman dropped audiences into a fraught moment on the Turtle Mountain Reservation in the mid-20th century.

Audio book clip: "Something is coming in the government," said Thomas, "They have a new plan. They always have a new plan," said Biboon. "This one takes away the treaties," said Thomas. "For all the Indians or just us," said Biboon. "All."

Brooke Gladstone: These books, different as they are, do more than transport us to another time and focusing on lesser-known histories, they ask us to consider what's worth remembering at all. In a piece that first ran in March, On The Media producer, Eloise Blondiau chatted how his historical fiction became a rich resource for reckoning with our past.

Eloise Blondiau: Last year, Hilary Mantel, the historical novelist, died aged 70. In her memory, a lecture she gave for the BBC was recirculated.

Hilary Mantel: History is not the past. It's the method we've evolved of organizing our ignorance of the past.

Eloise Blondiau: History, Mantel says, is the record of what's left on the record. It's what's left in the sieve when the centuries have run through it.

Hilary Mantel: It's no more than the best we can do, and often it falls short of that.

Eloise Blondiau: At On The Media, we often examine the failings of our historical record, and many historical novelists have long engaged in the same project, to bring the dead back to life.

Audio book clip: I promoted you, I am responsible for your rise.

Eloise Blondiau: In her Wolf Hall trilogy, Mantel resurrected Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII. In the BBC's faithful adaptation, Boleyn confronts the King's advisor, Cromwell, who would plot her execution.

Audio book clip - Anne Boleyn: At the first opportunity you've betrayed me. Those who've been made can be unmade.

Audio book clip - Cromwell: I entirely agree.

Eloise Blondiau: Mantel's Boleyn is brave and erasable. She uses the little written evidence we have to tell us who Boleyn was, like a letter that told of Boleyn describing her imminent beheading defiantly.

Audio book clip - Anne Boleyn: I only have a little neck, so it'll be the work of a moment.

Eloise Blondiau: Mantel received pretty much every accolade a novelist can hope to win, but that almost didn't happen. When she first tried to get published, she ran up against the shabby reputation of historical fiction.

Alexander Manshel: Quite famously, Henry James wrote in a letter to a friend that the historical novel was, "Tainted by a fatal cheapness."

Eloise Blondiau: Alexander Manshel is a professor of literature at McGill University, and he's also my guide.

Alexander Manshel: So, the idea was that to actually access the historical past through fiction was an impossible task. The only people foolish enough to attempt it were those looking to make a quick buck on cheap thrills.

Eloise Blondiau: That doesn't mean it wasn't popular. Over the last century, millions of copies were sold. Think of Margaret Mitchell in the '30s, James Michener in the '60s and James Kloval and Ken Follett beginning in the '70s. That decade also saw the rise of these really funny sci-fi takes on the genre from authors like Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, and Ishmael Reed.

Alexander Manshel: Here are the example I think of. First, is Ishmael Reed's 1976 novel Flight to Canada, in which runaway slaves literally take flight aboard Air Canada Jet liners heading north, and Abraham Lincoln is assassinated live on satellite television. It's an absolutely wild novel.

Eloise Blondiau: But, overall historical novels were considered more popular than prestigious, which might explain Mantel's challenges early in her career.

Alexander Chee: When she hoped to debut with a 700-page novel about the French Revolution, publishers were absolutely against it.

Eloise Blondiau: The writer, Alexander Chee, wrote about Mantel's experience for the New Republic. You quote Mantel saying they didn't want another novel about high hair.

Alexander Chee: Yes. [chuckles] Not realizing, of course, that she would go on to become world-famous and a bestseller for her Wolf Hall novels.

Eloise Blondiau: Of course, Mantel got her historical fiction printed in the end, but it was only after she first had a successful contemporary novel published. For Chee, who began his writing career in the late 90s, the opposite was true. It took him two years to sell his contemporary novel, Edinburgh. During that process, he had an idea for a very different historical book. He had been reading something that offhandedly described an intriguing woman.

Alexander Chee: She was a favorite courtesan of the emperor Napoleon III. She loved to walk on her hands because she'd been an acrobat and ride horses bareback. I thought, wait a second, what happened to her?

Eloise Blondiau: He sent his agent a note about a book that he'd later call The Queen of the Night.

Alexander Chee: That was the one that they overwhelmingly wanted. Editor after editor kept saying, "Can he do that one first?"

Eloise Blondiau: You write, "It was five years later that I was ready to sell a second book, and that little paragraph of a historical novel sold in nine days."

Alexander Chee: Yes, it was incredibly peculiar. I should say I was paid over 10 times for my second historical novel what I was paid for my first novel.

Eloise Blondiau: Between 2000 and 2010 when Chee's book was picked up, Alexander Manshel found that 80% of the novels that were shortlisted for major American literary awards were set in the past. Like Mantel's Wolf Hall, Michael Chabon's, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, which was set in World War II, and Ian McEwan's own war novel, Atonement.

Movie clip - Cecilia: Robbie, didn't you read my letters? Had I been allowed to visit you, had they let me, every day, I would have been there every day.

Movie clip - Robbie: Yes, but if all we have rests on a few moments in a library three and a half years ago then I am not sure.

Eloise Blondiau: Accolades were plentiful for the 2005 novel March, which Geraldine Brooks wrote about the father of the girls of Little Women. They also loved Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie's, Half of a Yellow Sun about the Nigerian Civil War. So, why the about-face? Manshel notes that some novelists vying for highbrow prizes didn't want to date their work with tech that would seem old in just a few years.

Alexander Manshel: If you are a literary novelist, you are interested in having your work not only be read right now but having it last, having it survive to be read in the future. And so, when writers set their work in the historical past, they're also in a way claiming a timelessness.

Eloise Blondiau: While the promise of eternal relevance may have tempted some writers to try the genre, that doesn't quite account for the scale of historical fiction's dominance today. According to Manshel, there's one pioneer of historical novels who often gets overlooked. When he tells people about his research, he's met with a common refrain.

Alexander Manshel: People will say, "Oh, you mean like Hilary Mantel?" When I say, "No, I mean like Toni Morrison," there's this brief moment of pause. When we think about what the historical novel is and does and what it should do, we think about the courtly drama of Cromwell and Henry VIII. We're not thinking about a woman in Ohio in 1873.

Eloise Blondiau: While Mantel's most celebrated books focused on the giants of 16th-century England, Morrison's work exemplifies the expansion of the genre in a different direction in America. The retrieval of otherwise disregarded histories, often by writers of color.

Manshel: Morrison in her most iconic work, Beloved, coins the term rememory. This is the idea that history lives on in the present, even for those who haven't experienced it directly.

Eloise Blondiau: Beloved won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1988, and it was a finalist for the National Book Award. It's often described as a ghost story about how a mother is haunted after she killed her own baby to keep her from being raised in slavery.

Audio book clip - Toni Morrison: Some things you forget, other things you never do.

Eloise Blondiau: This is Morrison reading from Beloved.

Audio book clip - Toni Morrison: Places, places are still there. If a house burns down, it's gone, but the place, the picture of it stays, and not just in my rememory, but out there in the world.

Alexander Manshel: This idea that there are histories, especially traumatic histories for marginalized people in the United States that live on in the present was central to Morrison's entire body of work.

Eloise Blondiau: In the 80s and 90s, Morrison's success was accompanied by a shift in the institutions that recognized American novelists, universities, publishers, and award committees. They were admitting more people of color than they had before and recognizing more marginalized writers in turn.

Alexander Manshel: At the end of the 20th century, as more and more Black, Asian American, Latinx, Indigenous, and Jewish novelists were finally being recognized by the literary establishment, the vast majority of the work that was being celebrated was historical fiction.

Eloise Blondiau: Those authors, Manshel says, were popular in universities because they allowed professors to both teach great works of literature and introduce students to history they may not have encountered before. Between 1980 and 2010, over 90% of the novels by writers of color that were shortlisted for a major American literary prize were historical.

Manshel: I'm thinking here of writers like Toni Morrison, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Alice Walker. It's about lesser-known figures and lesser-known histories, and that's actually part of the project.

Eloise Blondiau: In the past decade or so, a new class of writers has carried forward this tradition of disrupting the prevailing historical narratives. Like Morrison, Colson Whitehead weaves fantasy into his books. He transforms the underground railroad route that enslaved people used to escape to freedom into a literal subway system.

TV show clip: Are we going down there?

TV show clip: Yes, indeed. Mind this water now.

TV show clip: After you.

Eloise Blondiau: In that book, Whitehead critiques the idea of linear, historical progress. His protagonist, Cora, escapes slavery only to find work in a museum as a performer in slavery reenactments. In this clip from the Amazon show, Cora fearfully watches white men practicing their role.

TV show clip: You see, let it flow. If you like, you could add some dialogue. You know why? Stupid animal. How you like that?

TV show clip: Oh, you've done this before I take it?

TV show clip: Ah, well, that was a lifetime ago. [laughs]

Eloise Blondiau: Several recent prize winners follow families across generations. In her 2016 debut, Homegoing, Yaa Gyasi charts the lineage of two sisters over 300 years. Beginning in 18th century Ghana, one sister is enslaved and taken to America while the other remains in Africa. In 2017, Pachinko by Min Jin Lee follows the journey of one family over eight decades, beginning with a young girl in Korea who moves to Japan, where her family is mistreated. The stories of these ordinary Koreans falling in love, struggling to pay their bills, amid the giant storylines of war and mass migration, were not ones that Lee had encountered as a history major in college.

Min Jin Lee: It was so clear to me that everybody that I cared about, all the people that I really valued, all these lives, important lives to me, were not included in history. I thought it's something that seemed quite untruthful.

Eloise Blondiau: The first line of Pachinko is, "History has failed us, but no matter."

Min Jin Lee: The more important statement, I believe, is the subordinate clause of the statement, "History has failed us, but no matter," because it is a statement of defiance. I'm saying it doesn't matter because we are history, and we will be included, and we will persist anyway.

Eloise Blondiau: With Pachinko in particular, you're also tapping into a collective grief for generations past. I wonder if you write as a way to contend with loss.

Min Jin Lee: Yes. I think that every honest storyteller is really experiencing a kind of loss. It could be of life, it could be of love, it could be of status, it could be of money, it could be of friendship, it could be of community, it could be of nation. Some things cannot be had again. If we lose a parent or a sibling or a lover to death, we cannot get that person again. I think that it's honest to say that I rail against death because we have the time that those who have died do not have.

Eloise Blondiau: For Lee, writing novels about the past is a way to shape the future.

Min Jin Lee: You and I are making history right now, Eloise. It's breathtaking when you think of it that way, that 50 years from now, most likely I'll be dead. Let's say someone was considering, "Well, what did people in 2023 think about historical novels?" perhaps our conversation would come up and then we are making history. With that knowledge, I feel concerned about the value and significance of you and me talking about this.

Eloise Blondiau: That feels like more pressure. [laughs]

Min Jin Lee: Maybe it is. I guess I think of it as what an extraordinary thing that we get to be included.

[music]

Toni Morrison: The past, I suspect's probably more infinite than the future.

Eloise Blondiau: Here's Toni Morrison again.

Toni Morrison: The point is that there are lessons to be learned there so that we don't have to do that again. There's garbage in it also that you can throw out. It's all information. It's all the way we were. It's all part of who we are.

Eloise Blondiau: History has never been just the purview of historians as powerful as they are. The more we all add to the record of our history, the truer it will be. No matter if those contributions are merely bits and pieces, tatted cloth, names on park benches, old maps, or pottery shards. Add the alchemy of the imagination and you have a novel, a gateway to our common humanity in every era. For On the Media, I'm Eloise Blondiau.

Brooke Gladstone: Thanks again to Alexander Manshel, who shared with us so much research from his forthcoming book, Writing Backwards; Historical Fiction, and the Reshaping of the American Cannon. It's available for pre-order from bookshop.org or wherever you get your books. Coming up, Three Lives in Four Objects. This is On the Media.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.