No Ado About Much

( Edward A. "Doc" Rogers / AP Images )

[CLIP]

BIDEN We're about to go into a dark winter. [END CLIP]

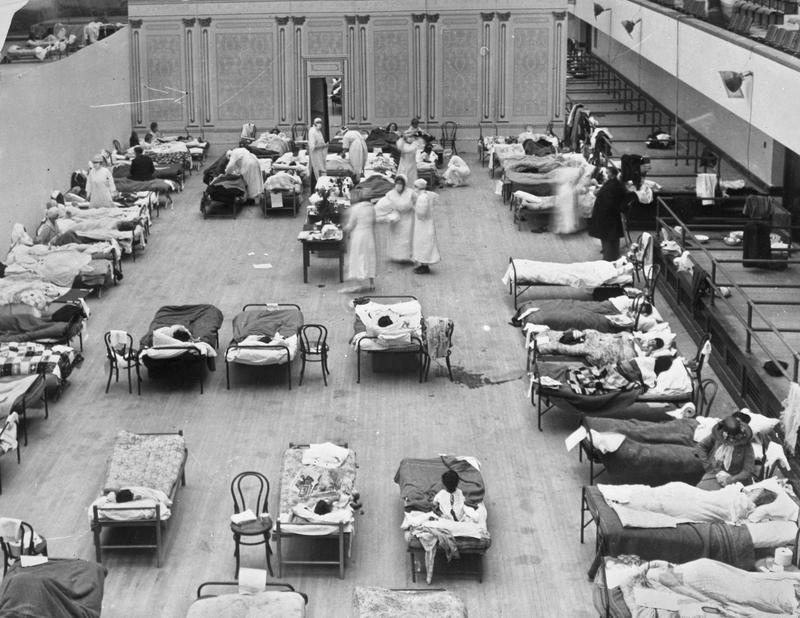

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. On this week's show, we remember how during the fall of 1918, the Spanish flu roared back with a similar vengeance and similarly incoherent and inconsistent advice from state public health authorities.

JOHN BARRY There are people dying 24 hours after the first symptoms. People very rapidly know they're being lied to. They lose all trust in authority; rumor and panic spread.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Plus, how and why America has always claimed ownership of the work of Britain's very own Will Shakespeare.

JAMES SHAPIRO It is explosive. It is potentially toxic. But that's why it speaks to us. We get it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It's all coming up, after this.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. Bob Garfield is out this week, I'm Brooke Gladstone. We have a lot of history coming up this hour, some sweet, most sour, pretty much all of it fascinating and all tending to the inevitable conclusion, to paraphrase Samuel Beckett, that the sun shines, having no alternative on the nothing new. We start with the specter still haunting us this Thanksgiving weekend.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Hospitalizations around the country have nearly doubled since late September. Some hospitals are already talking about rationing care,.

[CLIP]

NEW REPORT New cases, nearly triple the daily rate we were seeing just a few weeks ago. 44 states reporting a rise over the past week. Deaths also climbing. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

BIDEN We're about to go into a dark winter, a dark winter. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The murderous second wave is upon us. Just as the Spanish flu returned to menace in the fall of 1918. Ultimately, that flu killed more than 50 million people worldwide, including at least 675,000 Americans. Yet President Woodrow Wilson never addressed the nation's loss in any way. The first wave to hit Europe's First World War battlefields was in the spring. Not wanting to look weak, the Germans, the British, the French and nearly everyone else kept mum. About all this and more, we spoke earlier this year to John Barry, author of The Great Influenza The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. He told us it was only covered by newspapers in neutral Spain, which in fact is how the flu got its name.

JOHN BARRY Spain was not at war, so it didn't that its perhaps because the king himself got sick. So there was a lot of press about it and it got the name Spanish Flu. It was well-established elsewhere before it ever arrived in Spain.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We do know that it spread on our shores out of control from a military base outside of Boston. Right?

JOHN BARRY That was the first place that the second wave hit in the United States, I mean, the virus clearly changed in the first wave, it was generally mild. There were actually medical journal articles saying this looks and smells like influenza, but it's not killing enough people, so it's probably not influenza.

BROOKE GLADSTONE There was a mutation between the first and second wave?

JOHN BARRY Almost certainly. I mean, we can't prove that through molecular biology, but epidemiologically it seems quite certain.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide were infected. That would equal if you adjusted for population somewhere between 200 and 400 million, today. 675,000 killed in the U.S.

JOHN BARRY An estimated 28 percent of the U.S. population was hit.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The second wave was the deadliest here. It was in the fall of 1918, right at the end of the war. But what would we have seen if we'd cracked open a local newspaper in autumn 1918?

JOHN BARRY Lots of war coverage, but very little about the pandemic. Wilson had created something called the Committee for Public Information, a propaganda arm, and the architect for that committee said truth and false are aribitrary terms, but that is very little if it is true or false. So that was the attitude of the government propaganda machine. It also had passed a law making it possible, with 20 years in jail to quote, order, print, write or publish and disloyal, scurrilous, profane or abusive language by the former government of the United States.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This was the Sedition Act of 1918, right?

JOHN BARRY Yeah, a congressman was sentenced to more than 10 years in jail under that act. So publishers were threatened with it. Wilson himself at one point told a cousin, thank God for Abraham Lincoln, I won't make the mistakes he made, allowing a free press to flourish during the Civil War.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But Lincoln closed 300 newspapers!

JOHN BARRY Plenty of negative press about him in the reelection campaign of 1864. And again, going back to that committee of public information, a guy who ran that George Creel wanted to create, quote, one white hot mass with fraternity, devotion, courage and deathless determination. They really tried to make Americans conform that one way of thinking. I don't think we've ever experienced that before or since. More than the McCarthy period, more than any of the red scares, the press was determined to be as patriotic as anyone. For example, the Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote, What the Nation demands is that treason, whether thinly veiled or quite unmasked, to be stamped out. I could go on and give you other examples. You know, you had on the one hand, the carrot, the idea that the press was supposed to be patriotic and inspire people to help in the war effort, and on the other hand, you had the stick of that Sedition Act, so the result as a general rule was a very cooperative, complacent press where there was, in fact, fake news because they were cooperating with the government line.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But all this intensity was also employed to muzzle coverage of the flu.

JOHN BARRY Exactly. There was a concern that any negative news, no matter what it was about, would damage the war effort by hurting morale.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But surely there were exceptions. The Jefferson County Union Paper in Wisconsin - you've talked about?

JOHN BARRY Correct, when the pandemic hit there and they started to tell the truth about it, they were threatened with prosecution under the Sedition Act. There was no Tony Fauci back then. One national public health leader quoted by the Associated Press said this is no ordinary influenza by another name. Another said the so-called Spanish influenza is nothing more or less than old fashioned grippe.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That sounds a little familiar.

JOHN BARRY Yeah, a few miles outside Little Rock was Camp Pike. 8000 soldiers were admitted to the hospital in four days. The camp commandant stopped releasing the names of the dead. The doctors there wrote a colleague: Every corridor, and there are miles of them, have a double row of cots with influenza patients. There is only death and destruction. The camp called upon Little Rock to supply civilian doctors and nurses and linens and coffins and the Arkansas Gazette just a few miles away in its headline writes, quote, Spanish influenza is playing the Grippe, same old fever and chills. You have essentially the same thing happening everywhere. Des Moines, Iowa, for example, the city attorney was part of the emergency committee writing the response to influenza. He wrote Publishers', quote, I would recommend that if anything be printed in regard to the disease or be confined to simple preventative measures, something constructive rather than destructive, unquote. And of course, you know, that carries with it the potential for prosecution.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What was constructive, what was destructive in this formulation?

JOHN BARRY Public health guidance, such as keep your windows open, avoid crowds, washing your hands, things like that - that would be considered constructive. Actually, printing news of what was happening was destructive.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Hmm. You also had remarkable details about the Espionage Act that involved the post office.

JOHN BARRY Right, and the postmaster was not going to allow anything negative, and what they regard as negative was actually just the truth, in many occasions. Anything that they regard as depressant to morale. Back then, of course, many in the news media was distributed solely through the mail. So, that effectively was completely silencing publishers, effectively putting them out of business.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It would seem to be a terrifying time to be an American.

JOHN BARRY It was a violent, terrifying disease. People could turn so dark blue from lack of oxygen but I quoted one physician writing a colleague that he couldn't distinguish African-American soldiers from white soldiers because their pallor was so similar. In some camps, 15 percent of the soldiers with the disease had nosebleeds. But you could also bleed from your mouth and you could bleed even from your eyes and ears. And when they are being told that this is ordinary influenza by another name, there are people dying 24 hours after the first symptoms. People very rapidly know they're being lied to. They lose all trust in authority, rumor and panic spread. It leads to a fraying of society and the worst cases, almost a breakdown of society.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You contrast the cities of Philadelphia and San Francisco.

JOHN BARRY Philadelphia may be the most extreme example. Literally thousands of people are dying and they finally, belatedly closed schools and bars, and theaters and so forth, and finally took this act. One of the Philadelphia newspapers actually said, quote, This is not a public health measure. You have no cause for panic or alarm, unquote, beyond absurd. Of course, you're not going to believe anything you read either or that paper or any paper. In Philadelphia society really did almost begin to break down. There are reports of people starving to death because no one had the courage to bring them food. In San Francisco, by contrast, the mayor, medical leaders and the community business leaders, the trade union leaders all signed a joint statement in huge type in the newspaper full page said wear a mask and save your live. It turns out those maps were not very useful. But that is a very, very different message than this is ordinary influenza with another name. San Francisco functioned. It seemed to come together when schools closed, teachers volunteered even as ambulance drivers, which, of course, is a pretty risky thing to do. Compare that to Philadelphia, where people could starve to death because nobody had the courage to bring them food. I think it's directly related to the fact that people were told the truth and the leadership trusted the public. Both Philadelphia and San Francisco were extremely hard hit by the disease. San Francisco is right around fifth in the country in terms of excess mortality, which was about the same as Philadelphia. But in one city you can see an absolute fraying of society. And in the other city you see the community coming together and helping each other.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Woodrow Wilson got the flu. It resulted in intense disorientation, decreased mental functioning. That was a symptom of this particular pandemic. At the absolutely wrong time.

JOHN BARRY You know, it was widely noted that people did become extremely disoriented and in some cases psychotic and recovered, and Wilson got sick at Paris while negotiating the peace treaty. Everybody around him from Erwin Hoover, who was the White House officer that Herbert Hoover commented on, how they had never seen him like this. His mind wasn't functioning. German territories were essentially ceded to France. France was allowed to economically explore German regions. Germany was saddled with huge reparations payments. And essentially every historian of the rise of the Nazis credits or blames that peace treaty for part of the rise of Hitler and subsequently World War Two. John Maynard Keynes called Wilson the greatest fraud on Earth after that peace conference.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The greatest fraud on Earth. Wilson never, ever spoke about the flu, though, did he? We look at newspaper accounts, those are muzzled and confused. What were you able to find about how people understood what was happening or or how they mourned the dead or tried to protect themselves?

JOHN BARRY It was a very serious scientist named Victor Vaughn, who during the war, became a colonel, head of the communicable disease division for the Army. And right at the height he wrote at the current rate of acceleration continues for a few more weeks, civilization could easily disappear from the face of the earth. That is how bad it was beginning to get the happened right that right at the peak and things began to improve.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What about the artists? The novelists? We know Katherine Ann Porter wrote Pale Horse, Pale Rider, but there doesn't seem to be a lot written by observers, even by survivors.

JOHN BARRY You know, that has always puzzled me, the lack of literature about this. Nonetheless, it is clearly out there in the public mind. Christopher Isherwood was in Berlin in Berlin, stories from which great movie Cabaret came when the Nazis entered Berlin. You said you could feel it like influenza in your bones. This kind of sense of deep dread, and this is 15 years after the pandemic. You certainly expected this readers to recognize dread that he was referring to. So it was out there, even if people weren't writing about it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE There was a period of generations where there was nary a mention of the epidemic. I don't think I was an exception to the rule. We knew more about the bubonic plague than we knew about the 1918 pandemic. How do you account for that?

JOHN BARRY You know, it was so fast. That's part of it. Probably two thirds of the deaths worldwide occurred in a period of 14 or 15 weeks. And in any given community, it was roughly half that length of time. Influenza would hit a city in six weeks, seven weeks, eight weeks later, it was gone. You know, there may have been a third wave depending where that city was, but that would come months later. And the third wave was still lethal enough, but it was nothing compared to the second wave. You had this incredible brevity and life largely returned to normal pretty quickly, and it was ending almost simultaneously with the end of the war. November 11th, people are out celebrating practically to the moment in many cities that they were coming out of their lockdown. So I'm talking now I can sort of see part of the forgetfulness, except for those who had personally suffered. Two thirds of the dead were people aged 18 to 45 and the elderly hardly suffered at all. But kids under the age of five died at a rate equal today to all cause mortality for a period of 23 years. Just think of that. Kids dying today from all causes over a period of 23 years compressed into a period of a few weeks in 1918, and think of the toll that would take on parents.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But I have to ask you, 675000 dead in the U.S. adjusted for population, that would be two million. Yeah. And yet when it was over, was there ever a moment of national mourning? Was there ever a monument erected to the dead? Was there ever a recognition of the immense tragedy?

JOHN BARRY In terms of individual recollection? Yes, I remember telling my aunt, who was about 10 years old during a pandemic, what I was doing, and she essentially grasped her chest, practically started crying. So it was not something forgotten by individuals that tradgedy. As a society, no. I thought about this for 20 years and I haven't got a decent explanation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thanks so much.

JOHN BARRY Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE John Barry is the author of The Great Influenza The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History and professor at Tulane's School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. We first aired that interview in phase one, coming up, something new and completely different, Shakespeares Rough-and-ready relationship with American history. This is On the Media

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone on this unusual Thanksgiving weekend.

Today, the global pandemic leaves us with little to imagine, but plague. On the less dark side, we hear how Isaac Newton waiting out London's plague year of 1665 and forced isolation on his family farm, made stunning scientific breakthroughs in the name of William Shakespeare trended because we were reminded that he wrote King Lear while quarantined. But writing in The New York Times in March, Emma Smith argued that much of his life was marred by plague, and self isolating while writing Lear wouldn't have been a unique experience. In fact, Smith suggests, Shakespeare probably wrote most of his plays amid the threat of infectious disease. And yet the theme of plague pops up relatively rarely in his work. So taking a page out of the Bard's playbook, we at the show are going to interrupt our regularly scheduled doom and gloom to talk about Shakespeare, namely how he became a staple of American cultural and political life. James Shapiro is a professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. His most recent book is Shakespeare in a Divided America What His Plays Tell US About Our Past and Future. James, welcome back to OTM.

JAMES SHAPIRO It is a pleasure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So who owns Shakespeare? That's a big question you raise early and often in your book. It's a tension you trace back to the very beginning of American history.

JAMES SHAPIRO Everybody stakes a claim in Shakespeare. Going back to 1776 and even a few years before then, those on both sides of the cultural divide, whatever the cultural divide at that moment was, reached out to Shakespeare. Enlisted him in their casue.

BROOKE GLADSTONE John Adams said that the history plays were a roadmap to where we were heading. The treachery perfidy, treason, murder, cruelty, sedition and rebellions of rival and unbalanced factions.

JAMES SHAPIRO Could you imagine writing that in a letter to your son, the future sixth president of the United States? But he did. John Adams was looking around and he saw an America that was divided, that was factionalized, that was at risk. And he imagined one day and he even did a riff on Henry the Fifth in this imagining, one day we would have a president of the United States put in power by a foreign despot or dictator who had some kind of economic control over him. The divisions that splinter us today have been there from the founding of our republic, as has Shakespeare.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In 1877, a columnist in the New York Herald declared that Shakespeare was an American hero.

JAMES SHAPIRO You would think that having broken from Britain in 1776 and then went on to fight another war with them, that we would not adopt as our national poet, England's national poet, but in fact, we have. There's not an American writer, not Hemingway, not Emily Dickinson, not Faulkner, who is named as required reading by American high school and junior high school students. Shakespeare is.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Why do you think that is?

JAMES SHAPIRO We want to believe that what started in England ended in America. We keep wanting to rip or rest Shakespeare away from the English, who don't appreciate him, who don't value him.

BROOKE GLADSTONE How do they make that argument?

JAMES SHAPIRO We have a lot more Globe theaters or imitation Globe theaters in our country than they do in Britain. We have far more Shakespeare summer festivals here. There's really a determined effort to make Shakespeare fully American, sometimes in really disturbing ways, sometimes in just plain humorous ways.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So let's talk about immigration and race and difference generally, because in Shakespeare's comedies, which are actually any of the plays that have a happy ending, sort of you note that the marginalized are always the losers.

JAMES SHAPIRO One of the ways in which Shakespeare has made himself really useful to those who want to weaponize him is through the structure of his comedy. I mean, we all love the way they end in marriage and communal celebration. But that community at the end of all these joyous plays, is premised on somebody being kept out. You define yourself by who you don't admit. So whether it's Shylock at the end of the Merchant of Venice or Jaques in As You Like It, or Caliban is not allowed to go back with everybody to Italy at the end of The Tempest or Malvolio at the end of Twelfth Night. You define who's in by determining who's kept out, mocking them and excluding them. What better way to define who's an American than along this model that is time tested through Shakespearean comedy?

BROOKE GLADSTONE Pause for a moment at Caliban, in The Tempest. This beastly figure who in a 1916 production is a stand in for the unwashed immigrants.

JAMES SHAPIRO Yeah, those are my grandparents, I suppose, on both sides. Living on the Lower East Side who are called by sociologists of the day, kind of Caliban figures. Just look at their faces, look at their shoulders as they go to and from the sweatshops.

[CLIP]

CALIBAN Sometimes am I all, wound with adders with cloven tongues do they hiss me into madness. [END CLIP]

JAMES SHAPIRO Caliban is in the late 19th century, increasingly seen as a Darwinian missing link, half man, half beast. And he became a kind of metaphor, or stand-in for those who were not fully accepted into white Anglo-Saxon American culture. A very talented playwright named Percy McKaye wrote this great mask of Caliban, Caliban by the Yellow Sand and the Caliban figure was supposed to be somebody who was educated successfully into American culture, if you will. Except every 15 or 20 minutes he tries to assault or rape Maranda. He's incorrigible. Even as this was being staged, it undermined its message of acceptance and only underscored that America could not absorb the Caliban of this world.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Now, Othello is no comedy, but he reverberates through history. You recall that John Quincy Adams, who was well known as an abolitionist, had a surprisingly visceral distaste for Othello.

JAMES SHAPIRO It's the saddest chapter in my book. Othello is a fundamental American play. Its history here is completely different from its history in England. In England in 1825, an African-American was actually performing the role of Othello on the London stage. But it would be over 100 years before Paul Robeson could do the same on Broadway.

[CLIP]

OTHELLO My wife? What wife? I have no idea wife. Oh, insupporter, oh heavy heart. Me thinks it should be a huge eclipse of sun and moon, and that the affrighted globe should yawn at alteration. [END CLIP]

JAMES SHAPIRO The story of John Quincy Adams is the story of my book, which has as its argument, Americans are really not good at talking with each other about things they disagree vehemently about or things they don't want to admit about themselves. John Quincy Adams, as you say, great abolitionist, fought the Amistad case in front of the Supreme Court after he served as America's sixth president, joined the House of Representatives to fight slavery. And yet he could not wrap his head around the idea of a white woman sleeping with a black guy. Just could not do it. He was invited to what turned out to be the worst dinner party in history. He was seated next to the superstar British actress Fanny Campbell, and he spent the evening mansplaining Shakespeare to her, including saying that Bella was disgusting.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And the person most to blame in the play is Desdemona.

JAMES SHAPIRO Absolutely. She she doesn't respect male authority. And she she marries a black guy. And John Quincy Adams says in getting kind of strangled and smothered to death again, she got what she deserved. What do you think when one of the great opponents of slavery is actually thinking this stuff? And of course, many people think this stuff, but they don't say it or write it. And after that terrible dinner party, she went home, wrote up her notes, and two years later published the conversation. He mortified, writes this essay on the character of Desdemona, trashing her for falling in love and marrying a black guy. He just couldn't understand why everybody didn't kind of go along and accept his view. And it appeared in major periodicals. And he wrote essays saying this. In fact, the real shocker was Fannie Campbell wrote a letter that was later published to a friend in which she quotes Adams using the N-word to describe Othello. I just can't believe it. You want to imagine a kind of more pristine American past? One of the ways of learning what we weren't taught about American history in high school is through how we talk about Shakespeare.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In your chapter on Manifest Destiny, when the nation embarked on exploiting or exterminating nonwhite people coast to coast, you observed an interesting evolution in the notion of masculinity. One that played out both in that policy and in the productions of Romeo and Juliet.

JAMES SHAPIRO If you look at the American stage at this time, the model of what a man should be, which is sober and serious, hard working, is replaced by a blustery, aggressive, heavily sexualized, violent type. The upshot of this was, when it came to casting Romeo, every guy who was trying to play that role - failed in it. Because at some points in the play has to be, as Shakespeare calls him, effeminate. And at other times you have to pick up a sword and kill people and be really kind of masculine. So women began taking over the part. 20 women played Romeo at this time, and the greatest of them was Charlotte Cushman. It tells you something about changing roles of masculinity when only a lesbian can play Romeo successfully in America. The most amazing thing I stumbled on in writing and researching this book was on the eve of the Mexican-American War when 4000 American troops are gathered on the border to cross the Rio Grande and the officers decided to build a theater and put on plays with all male casts. And one of the first plays they did was Othello. And they couldn't find somebody to play Desdemona.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And then they found this rather slight, pretty young officer...

JAMES SHAPIRO ...Who looked great in a dress, Ulysses S. Grant. This is kind of pre 50 dollar bill Grizzled Grant. He was girlish in those days. The guy playing Othello couldn't get up enough emotional excitement they sent to New Orleans for a professional actress to sub for Grant who went on to bigger and better things. But it was great to think of a future American president playing a woman in love with a black man. I mean, that tells you something about where this country has been.

BROOKE GLADSTONE British portrayals of Shakespeare protagonists, especially Macbeth and Hamlet, were very different from the American portrayals.

[CLIP]

MACBETH Do not muse at me, my most worthy friends. I have a strange infirmity. [END CLIP]

JAMES SHAPIRO True. In part because the lead American actor at this time, a guy named Forrest.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Edwin Forrest.

JAMES SHAPIRO When they found him finally at the end of his career, dead in bed, they found a pair of hand weights at the foot of his bed. He was one of the early advocates of the pumped up actor. His first great homegrown male Shakespearian actor, and he defined it in opposition to that kind of thoughtful, brooding, reflective English Shakespearean.

[CLIP]

HAMLET Am I a Coward? Who calls me villain? Breaks my pate across? Plucks off my beard and blows it in my face? Tweaks me by the nose? Gives me the lie of the throat? As deep as to the lungs? Who does me this? [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Macbeth and Hamlet, who we just heard were portrayed as warriors in America. They even cut the parts where they looked weak out of the plays. And that brings us to Lincoln's assassination.

JAMES SHAPIRO John Wilkes Booth is notorious as the man who assassinated Lincoln at Ford's Theater in April 1865. But he was also one of the great Shakespeare actors of his day.

BROOKE GLADSTONE John Wilkes Booth played Macbeth. What, about a hundred times? But it was the character of Brutus in Julius Caesar that seems to have been the true inspiration for what he did.

JAMES SHAPIRO He loved the character of Brutus, as many in 19th century America did. This is a man who opposed tyranny. And the South saw Lincoln as a tyrant. Booth only acted once in this play, but he recited the speeches all the time. After assassinating Lincoln, he leaped onto the stage, a little leaping trick he stole from his Macbeth productions, and he shouted sic semper tyrannis, thus always with tyrants, playing momentarily the part of an American Brutus right after his assassination of Lincoln. .

BROOKE GLADSTONE Talk about the very controversial production of Julius Caesar you are involved in a few years back, put on by the Public Theater in Central Park, it roiled the political right.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Conservative protesters disrupt the controversial performance of Julius Caesar in New York City. [END CLIP].

[CLIP]

TUCKER CARLSON Are you a sad progressive who dreams about President Trump being knifed to death? Well, you're you're in luck. A new production of Julius Caesar in New York let you live out your fantasy. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Caesar was dressed like Trump had certain of his mannerisms. Plus, a wife, Calpurnia, who sported a Slavic accent. And, of course, he's murdered in cold blood. Can you blame the right for being upset?

JAMES SHAPIRO I don't blame the right for being upset any more than I would blame the left for being upset with a year or so earlier, Rob Melrose's production of Julius Caesar that had an Obama lookalike assassinated on stage. The tradition of Julius Caesar in this country changed permanently when Orson Welles staged this play in 1937 at the Mercury Theater.

[CLIP]

ORSON WELLES If there be any and this assembly, any dear friend of Caesar's to him, I say that Brutus does love to Caesar was no less than his. If then that friend demand why Brutus rose against Caesar. This is my answer. Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more. [END CLIP]

JAMES SHAPIRO His Caesar was just like Mussolini, and he completely politicized how this play was done. It became a template for how we did Caesar after that. Oskar Eustis, the artistic director of Public Theater, he wanted to show that saving democracy by undemocratic means, like killing a Trump like Caesar, was a greater disaster than anything else. I think he wanted to create a sense of whiplash in that liberal audience at the Delacorte Theater. And one of the ways he did that was to have fifty actors hidden throughout the audience so that when Brutus and the conspirators kill the Trump like Caesar, they're screaming, they're yelling, they're castigating him for doing that. They're calling him out. The problem was when real protesters followed the fake protesters. Audience members didn't know where the protests were coming from or who was protesting what. So that invasion, if you will, of the Delacourt by protesters who were paid to disrupt the show, ruined the possibility of conversation and dialog. Or maybe we're just not ready yet for conversation and dialog in this country.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But Shakespeare does seem to be used like the Bible in the sense that anyone can find a defense for whatever they believe in his text. Do you think his message, his intentions, his morals were more explicit in Elizabethan times and the times they were written?

JAMES SHAPIRO I don't think so. And I think that's why we still turn to Shakespeare. Shakespeare presents America's worst nightmares, the assassination of a ruler, a black man sleeping with a white woman, a Jew cutting the pound of flesh from a Christian. This is not the stuff in the Bible, and when we stage these things, we're forced to confront the stuff we don't really like confronting as Americans. It's right in our face.

BROOKE GLADSTONE James Shapiro, author of Shakespeare in a Divided America, coming up on the relatively lighter side, the Bard's use and abuse in American sexual politics. This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. There's a fair amount of hankie panky in Shakespeare's plays, cross-dressing, animal attraction, but very little sex. Maybe Romeo and Juliet. There's passionate but platonic same sex love. In his day, same-sex sex was a capital offense. The sexuality of Shakespeare himself is a matter of speculation. There's plenty of sexual politics in his play's, though. We see women sometimes defending, sometimes demeaning themselves. We see men sometimes punished for their greed or vanity or cruelty, sometimes not. In The Taming of the Shrew, fortune-hunting Petruchio is prone to all three, yet he succeeds in starving and bullying, unwilling Ill-Tempered Kate into a parent submission. And the musical take off Kiss me Kate, two divorced actors find themselves playing Kate and Petruchio, and once again, the rascal has his way. On stage and back stage change. James Shapiro is one of our leading Bards of the Bard. Let's start with the original boy.

JAMES SHAPIRO That's a radioactive story. I mean, it ends with a woman putting her hand beneath her husband's foot

[CLIP]

KATHARINA My reason haply more, to bandy word for word and frown for frown. But now I see our lances are but straws. Come and place your hands below your husband's foot, and token of which duty, if he please. My hand is ready, may it do him ease. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Could you describe the evolution of Kiss Me, Kate, from Taming of the Shrew?

JAMES SHAPIRO From 1941 to 45 American women are told, become Rosie the Riveter. Enter the workforce, become independent financially and personally.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You observe that at some point it's really common in film and movies and on stage to depict a woman being spanked. And it changed practically over the course of a few months.

JAMES SHAPIRO Women are told by the government, get out of the way, become the happy housewife and your it's going to be to just grin and bear it. And I'm really not exaggerating. Kiss Me, Kate is written at that moment, and at the center of it is something I was never in Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew. Being spanked on stage. And spanking a woman is not only domestic violence, but it turns her into a child in a very explicit way.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It was on all the posters.

JAMES SHAPIRO And it was in The New York Times when they reviewed it. That's the image from this play that stuck.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Now there is a warring couple playing the two leads, Kate, in Shakespeare's play. She's too much of a shrew for anyone to actually want to marry, so she's auctioned off to this guy passing through named Petruchio. The backstage story seems to follow, similarly, at least the woman decides it is the better part of valor to simply bow to her husband's will wink, wink, nod, nod, or maybe not. You tell a very interesting story about Cole Porter, who found himself with an almost intractable conundrum.

JAMES SHAPIRO You know that two great collaborative geniuses behind this musical. One is Bella Spewack, one of the two women writing Broadway plays at this time, and the other is the great lyricist Cole Porter. This is a hard story to tell. Front stage, you have this restaging of Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew. Backstage, have gang members collecting debts, divorce. There are white people. There are black people. It's kind of like real life, backstage and front stage is this artificial Shakespearian world. And they couldn't figure out how to end the play. And they bring out a couple of gangsters to sing a rousing song, Brush Up Your Shakespeare, which people love, and at the finale of the whole musical as well. And it's a song about basically justifying domestic violence.

You know, five years after this brilliant stage version Kiss Me, Kate became a movie that was completely sanitized and all the African-American stuff is removed. And the story in which a woman has real choices is by the early 1950s, a story in which women no longer have choices.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So now take us through these strange and perilous journey that was the multiple Oscar winning film Shakespeare in Love.

[CLIP]

THOMAS And I leave to be if I be -

WILL Take off your hat.

THOMAS My hat?

WILL Where'd you learn how to do that?

THOMAS I -.

WILL Let me see you, take off your hat!

THOMAS Are you Ma- Master Shakespeare?

WILL Wait, there! Wait there! [END CLIP]

JAMES SHAPIRO The first script of Shakespeare in Love was written by a screenwriter named Mark Norman and he building upon what we know about Shakespeare from the sonnets and much else imagined a Shakespeare who's married to Anne Hathaway, but who discovers himself falling in love with another man and comes to terms with that. It was way too far ahead of what Hollywood thought Americans were ready for, so they brought in Tom Stoppard, the greatest English playwright, Czech born, but he's British. Then he gets rid of the gay stuff. And the infamous Harvey Weinstein is the producer trying to bring this thing to the point where it's going to win a gazillion Academy Awards. He's leaning on the director and he's leaning on Stoppard to fix the ending because Americans don't like adultery. And Harvey Weinstein ideas turn the female lead, the Gwyneth Paltrow character, into a woman you keep on the side and throw parts to in exchange for sex. Or in other words, turn into the Harvey Weinstein story. And Stoppard luckily resisted that. And the final film version gave Americans just what they wanted.

[CLIP]

WILL If I could write the beauty of our eyes. I was born to look at them myself.

THOMAS A-and her lips?

WILL Her lips, the early morning rose with wither on the branch, if it could feel envy.

THOMAS And her voice like lark dong.

WILL Deeper, softer. None of your twittering that's nightingales from my garden before they interrupt her song.

THOMAS Oh she sings too?

WILL Constantly. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE You also talk about who gets to perform Shakespeare. What does color-blind gender-blind casting mean in the current American context?

JAMES SHAPIRO To be fully American is to be able to be in a Shakespeare play. And one of the most poignant stories I came across while researching this book was a short story by Toshio Mori, a Japanese American who was born in the Bay Area and was moved at the beginning of the Second World War. Like many Japanese Americans to the Topaz relocation camp in Utah and he writes a story called Japanese Hamlet about a young Japanese man whose only desire in life is to play Hamlet and nobody can bring themselves to tell him it ain't going to happen. It's another way of getting at who we really think is fully American.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Is there any one way that Shakespeare's texts can serve as a framework for historical memory?

JAMES SHAPIRO I think they help us see what has been airbrushed out of the story we like to tell ourselves, and I actually think Shakespeare is a terrific force for good. I speak with a lot of people who are conservatives, who love Shakespeare. I speak with a lot of people who are liberals, who love Shakespeare. There's not a lot we actually can talk about and share in this country. I like to think that if we are going to do some healing in a post coronavirus world. Theaters, as the were for Shakespeare, who lived through an age of plague. They're are places where people flock to after trauma. And I'm hoping that they are going to provide some kind of clarity and solace as we put our nation back together again.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It's funny you said, you know, people on the right love Shakespeare and people on the left love Shakespeare. And you'd expect that of something that was blandly, broadly appealing. And yet it's quite the reverse. His body of work is almost combustible.

JAMES SHAPIRO It is. And that's the great secret of Shakespeare. It is explosive. It is potentially toxic, but that's why it speaks to us. We get it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thank you so much.

JAMES SHAPIRO It is always so much fun speaking with you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE James Shapiro is the author of Shakespeare in a Divided America when his plays tell us about our past and Future.

And that's the show. On the Media is produced by Alana Cassanova-Burgess, Micah Loewinger, Leah Feder, Jon Hanrahan, and Eloise Blondiau with help from Ava Sasani. Xandra Ellin wrote our newsletter. Our technical director is Jennifer Munsen, our engineers this week were Adrianne Lilly and Josh Hahn. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media, is a production of WNYC Studios. Bob Garfield will be back next week. I'm Brooke Gladstone and have a happy Thanksgiving.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.