Why The Press Downplayed the 1918 Flu

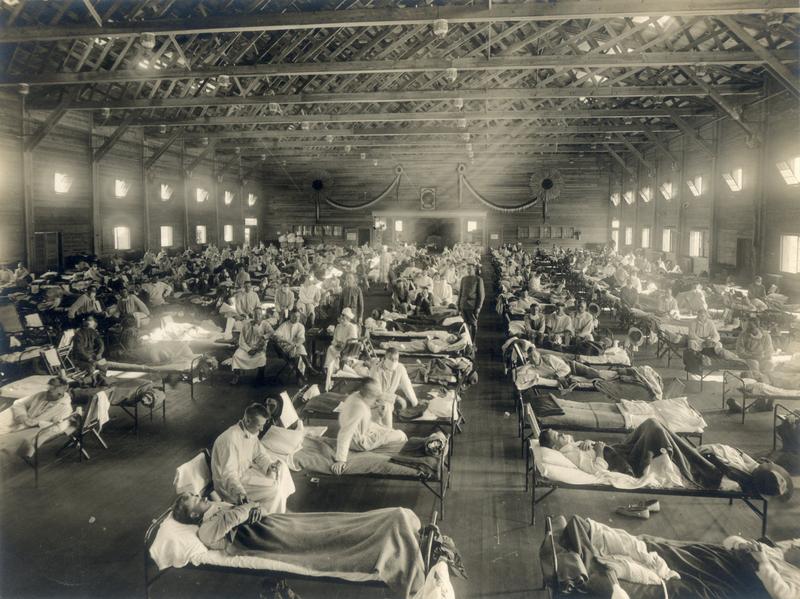

( Armed Forces Institute of Pathology/National Museum of Health and Medicine, distributed via the Associated Press )

[CLIP]

BIDEN We're about to go into a dark winter. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. On this week's show, we remember how during the fall of 1918, the Spanish flu roared back with a similar vengeance and similarly incoherent and inconsistent advice from state public health authorities.

JOHN BARRY There are people dying 24 hours after the first symptoms. People very rapidly know they're being lied to. They lose all trust in authority; rumor and panic spread.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Plus, how and why America has always claimed ownership of the work of Britain's very own Will Shakespeare.

JAMES SHAPIRO It is explosive. It is potentially toxic. But that's why it speaks to us. We get it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It's all coming up, after this.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. Bob Garfield is out this week, I'm Brooke Gladstone. We have a lot of history coming up this hour, some sweet, most sour, pretty much all of it fascinating and all tending to the inevitable conclusion, to paraphrase Samuel Beckett, that the sun shines, having no alternative on the nothing new. We start with the specter still haunting us this Thanksgiving weekend.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Hospitalizations around the country have nearly doubled since late September. Some hospitals are already talking about rationing care,.

[CLIP]

NEW REPORT New cases, nearly triple the daily rate we were seeing just a few weeks ago. 44 states reporting a rise over the past week. Deaths also climbing. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

BIDEN We're about to go into a dark winter, a dark winter. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The murderous second wave is upon us. Just as the Spanish flu returned to menace in the fall of 1918. Ultimately, that flu killed more than 50 million people worldwide, including at least 675,000 Americans. Yet President Woodrow Wilson never addressed the nation's loss in any way. The first wave to hit Europe's First World War battlefields was in the spring. Not wanting to look weak, the Germans, the British, the French and nearly everyone else kept mum. About all this and more, we spoke earlier this year to John Barry, author of The Great Influenza The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. He told us it was only covered by newspapers in neutral Spain, which in fact is how the flu got its name.

JOHN BARRY Spain was not at war, so it didn't that its perhaps because the king himself got sick. So there was a lot of press about it and it got the name Spanish Flu. It was well-established elsewhere before it ever arrived in Spain.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We do know that it spread on our shores out of control from a military base outside of Boston. Right?

JOHN BARRY That was the first place that the second wave hit in the United States, I mean, the virus clearly changed in the first wave, it was generally mild. There were actually medical journal articles saying this looks and smells like influenza, but it's not killing enough people, so it's probably not influenza.

BROOKE GLADSTONE There was a mutation between the first and second wave?

JOHN BARRY Almost certainly. I mean, we can't prove that through molecular biology, but epidemiologically it seems quite certain.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide were infected. That would equal if you adjusted for population somewhere between 200 and 400 million, today. 675,000 killed in the U.S.

JOHN BARRY An estimated 28 percent of the U.S. population was hit.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The second wave was the deadliest here. It was in the fall of 1918, right at the end of the war. But what would we have seen if we'd cracked open a local newspaper in autumn 1918?

JOHN BARRY Lots of war coverage, but very little about the pandemic. Wilson had created something called the Committee for Public Information, a propaganda arm, and the architect for that committee said truth and false are aribitrary terms, but that is very little if it is true or false. So that was the attitude of the government propaganda machine. It also had passed a law making it possible, with 20 years in jail to quote, order, print, write or publish and disloyal, scurrilous, profane or abusive language by the former government of the United States.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This was the Sedition Act of 1918, right?

JOHN BARRY Yeah, a congressman was sentenced to more than 10 years in jail under that act. So publishers were threatened with it. Wilson himself at one point told a cousin, thank God for Abraham Lincoln, I won't make the mistakes he made, allowing a free press to flourish during the Civil War.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But Lincoln closed 300 newspapers!

JOHN BARRY Plenty of negative press about him in the reelection campaign of 1864. And again, going back to that committee of public information, a guy who ran that George Creel wanted to create, quote, one white hot mass with fraternity, devotion, courage and deathless determination. They really tried to make Americans conform that one way of thinking. I don't think we've ever experienced that before or since. More than the McCarthy period, more than any of the red scares, the press was determined to be as patriotic as anyone. For example, the Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote, What the Nation demands is that treason, whether thinly veiled or quite unmasked, to be stamped out. I could go on and give you other examples. You know, you had on the one hand, the carrot, the idea that the press was supposed to be patriotic and inspire people to help in the war effort, and on the other hand, you had the stick of that Sedition Act, so the result as a general rule was a very cooperative, complacent press where there was, in fact, fake news because they were cooperating with the government line.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But all this intensity was also employed to muzzle coverage of the flu.

JOHN BARRY Exactly. There was a concern that any negative news, no matter what it was about, would damage the war effort by hurting morale.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But surely there were exceptions. The Jefferson County Union Paper in Wisconsin - you've talked about?

JOHN BARRY Correct, when the pandemic hit there and they started to tell the truth about it, they were threatened with prosecution under the Sedition Act. There was no Tony Fauci back then. One national public health leader quoted by the Associated Press said this is no ordinary influenza by another name. Another said the so-called Spanish influenza is nothing more or less than old fashioned grippe.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That sounds a little familiar.

JOHN BARRY Yeah, a few miles outside Little Rock was Camp Pike. 8000 soldiers were admitted to the hospital in four days. The camp commandant stopped releasing the names of the dead. The doctors there wrote a colleague: Every corridor, and there are miles of them, have a double row of cots with influenza patients. There is only death and destruction. The camp called upon Little Rock to supply civilian doctors and nurses and linens and coffins and the Arkansas Gazette just a few miles away in its headline writes, quote, Spanish influenza is playing the Grippe, same old fever and chills. You have essentially the same thing happening everywhere. Des Moines, Iowa, for example, the city attorney was part of the emergency committee writing the response to influenza. He wrote Publishers', quote, I would recommend that if anything be printed in regard to the disease or be confined to simple preventative measures, something constructive rather than destructive, unquote. And of course, you know, that carries with it the potential for prosecution.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What was constructive, what was destructive in this formulation?

JOHN BARRY Public health guidance, such as keep your windows open, avoid crowds, washing your hands, things like that - that would be considered constructive. Actually, printing news of what was happening was destructive.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Hmm. You also had remarkable details about the Espionage Act that involved the post office.

JOHN BARRY Right, and the postmaster was not going to allow anything negative, and what they regard as negative was actually just the truth, in many occasions. Anything that they regard as depressant to morale. Back then, of course, many in the news media was distributed solely through the mail. So, that effectively was completely silencing publishers, effectively putting them out of business.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It would seem to be a terrifying time to be an American.

JOHN BARRY It was a violent, terrifying disease. People could turn so dark blue from lack of oxygen but I quoted one physician writing a colleague that he couldn't distinguish African-American soldiers from white soldiers because their pallor was so similar. In some camps, 15 percent of the soldiers with the disease had nosebleeds. But you could also bleed from your mouth and you could bleed even from your eyes and ears. And when they are being told that this is ordinary influenza by another name, there are people dying 24 hours after the first symptoms. People very rapidly know they're being lied to. They lose all trust in authority, rumor and panic spread. It leads to a fraying of society and the worst cases, almost a breakdown of society.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You contrast the cities of Philadelphia and San Francisco.

JOHN BARRY Philadelphia may be the most extreme example. Literally thousands of people are dying and they finally, belatedly closed schools and bars, and theaters and so forth, and finally took this act. One of the Philadelphia newspapers actually said, quote, This is not a public health measure. You have no cause for panic or alarm, unquote, beyond absurd. Of course, you're not going to believe anything you read either or that paper or any paper. In Philadelphia society really did almost begin to break down. There are reports of people starving to death because no one had the courage to bring them food. In San Francisco, by contrast, the mayor, medical leaders and the community business leaders, the trade union leaders all signed a joint statement in huge type in the newspaper full page said wear a mask and save your live. It turns out those maps were not very useful. But that is a very, very different message than this is ordinary influenza with another name. San Francisco functioned. It seemed to come together when schools closed, teachers volunteered even as ambulance drivers, which, of course, is a pretty risky thing to do. Compare that to Philadelphia, where people could starve to death because nobody had the courage to bring them food. I think it's directly related to the fact that people were told the truth and the leadership trusted the public. Both Philadelphia and San Francisco were extremely hard hit by the disease. San Francisco is right around fifth in the country in terms of excess mortality, which was about the same as Philadelphia. But in one city you can see an absolute fraying of society. And in the other city you see the community coming together and helping each other.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Woodrow Wilson got the flu. It resulted in intense disorientation, decreased mental functioning. That was a symptom of this particular pandemic. At the absolutely wrong time.

JOHN BARRY You know, it was widely noted that people did become extremely disoriented and in some cases psychotic and recovered, and Wilson got sick at Paris while negotiating the peace treaty. Everybody around him from Erwin Hoover, who was the White House officer that Herbert Hoover commented on, how they had never seen him like this. His mind wasn't functioning. German territories were essentially ceded to France. France was allowed to economically explore German regions. Germany was saddled with huge reparations payments. And essentially every historian of the rise of the Nazis credits or blames that peace treaty for part of the rise of Hitler and subsequently World War Two. John Maynard Keynes called Wilson the greatest fraud on Earth after that peace conference.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The greatest fraud on Earth. Wilson never, ever spoke about the flu, though, did he? We look at newspaper accounts, those are muzzled and confused. What were you able to find about how people understood what was happening or or how they mourned the dead or tried to protect themselves?

JOHN BARRY It was a very serious scientist named Victor Vaughn, who during the war, became a colonel, head of the communicable disease division for the Army. And right at the height he wrote at the current rate of acceleration continues for a few more weeks, civilization could easily disappear from the face of the earth. That is how bad it was beginning to get the happened right that right at the peak and things began to improve.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What about the artists? The novelists? We know Katherine Ann Porter wrote Pale Horse, Pale Rider, but there doesn't seem to be a lot written by observers, even by survivors.

JOHN BARRY You know, that has always puzzled me, the lack of literature about this. Nonetheless, it is clearly out there in the public mind. Christopher Isherwood was in Berlin in Berlin, stories from which great movie Cabaret came when the Nazis entered Berlin. You said you could feel it like influenza in your bones. This kind of sense of deep dread, and this is 15 years after the pandemic. You certainly expected this readers to recognize dread that he was referring to. So it was out there, even if people weren't writing about it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE There was a period of generations where there was nary a mention of the epidemic. I don't think I was an exception to the rule. We knew more about the bubonic plague than we knew about the 1918 pandemic. How do you account for that?

JOHN BARRY You know, it was so fast. That's part of it. Probably two thirds of the deaths worldwide occurred in a period of 14 or 15 weeks. And in any given community, it was roughly half that length of time. Influenza would hit a city in six weeks, seven weeks, eight weeks later, it was gone. You know, there may have been a third wave depending where that city was, but that would come months later. And the third wave was still lethal enough, but it was nothing compared to the second wave. You had this incredible brevity and life largely returned to normal pretty quickly, and it was ending almost simultaneously with the end of the war. November 11th, people are out celebrating practically to the moment in many cities that they were coming out of their lockdown. So I'm talking now I can sort of see part of the forgetfulness, except for those who had personally suffered. Two thirds of the dead were people aged 18 to 45 and the elderly hardly suffered at all. But kids under the age of five died at a rate equal today to all cause mortality for a period of 23 years. Just think of that. Kids dying today from all causes over a period of 23 years compressed into a period of a few weeks in 1918, and think of the toll that would take on parents.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But I have to ask you, 675000 dead in the U.S. adjusted for population, that would be two million. Yeah. And yet when it was over, was there ever a moment of national mourning? Was there ever a monument erected to the dead? Was there ever a recognition of the immense tragedy?

JOHN BARRY In terms of individual recollection? Yes, I remember telling my aunt, who was about 10 years old during a pandemic, what I was doing, and she essentially grasped her chest, practically started crying. So it was not something forgotten by individuals that tradgedy. As a society, no. I thought about this for 20 years and I haven't got a decent explanation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thanks so much.

JOHN BARRY Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE John Barry is the author of The Great Influenza The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History and professor at Tulane's School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. We first aired that interview in phase one, coming up, something new and completely different, Shakespeares Rough-and-ready relationship with American history. This is On the Media

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.