How It Started, How It's Going

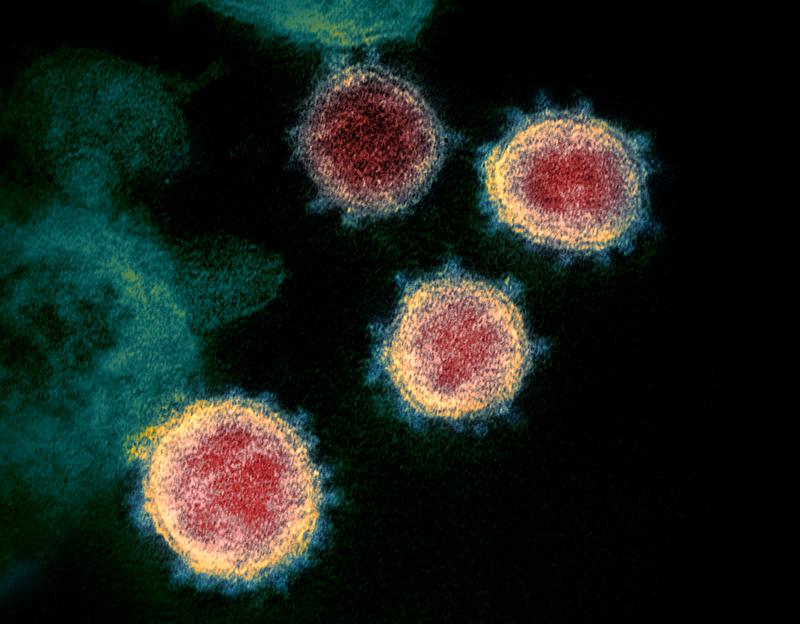

( NIAID-RML / Associated Press )

How it Started, How it's Going

ALINA CHAN We are in this pandemic that's been ongoing for about one and a half years now, there has been no actual investigation of how it began.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We know it's likely covid-19 came from a bat, but how did it get to us? From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. While the origin story is still being pieced together, the life saving answers in aerosol science are just beginning to get their due.

MEGAN MOLTENI What the past year has demonstrated to people is that aerosol science isn't just about climate change and hairspray, but it has this whole other application in the world of infectious diseases.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Plus, a buzzword among online futurists is the metaverse, but human beings have always looked for ways to escape reality.

GENE PARK I see a lot of similarities between drug experiences and virtual worlds and video games to even a Travis Scott concert while on Fortnite definitely felt like a very surreal, trippy experience.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It's all coming up after this.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Bob Garfield is out this week, and as many of you know by now – every week, having been fired after a warning and other efforts at amelioration for a pattern of bullying behavior. The entire staff agreed with that decision. The problem was not over passionate discourse. We don't fear that, we've even put some of our own on the radio, nor was it merely about yelling, but there's not much more I can say. Look, you know how this works: one side, as an individual is free to present their case however they see it, or wish to see it. They may describe their conduct in ways the other side might not even recognize, but that other side cannot engage because they're part of a bigger enterprise that balances many concerns, including legal ones. I know it's unsatisfying as much for a show as deeply devoted to transparency as ours as for some of you. But even if we could be totally transparent, the view would likely still be obscured under a heap of he said, they said. In the end it really comes down to trust, most especially and relevantly in the show and what it offers today, next week and the week after that. And so dear listeners on with the show.

Back when the pandemic started so many lifetimes ago, we, that is to say, all the humans on the planet, were faced with a host of questions. How does the virus that causes Covid-19, called Sars-cov-2, spread? How do we protect ourselves? And somewhere further down the list, amidst so much confusion and loss, how did it start infecting humans?

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT As scientists work to contain the coronavirus, researchers are still trying to figure out where it came from. Early research suggests human picked up the coronavirus from animals, possibly bats. [END CLIP].

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT We know it's very similar to the virus in the back, but did it go through an intermediate species? So this is a question we all need answered. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE One possible scenario emerged early and then promptly retreated from mainstream scientific discourse, the theory that it had leaked from the lab. It's an idea that hinges on two key facts. One, that the first outbreak of the virus occurred in Wuhan, China, and two, that Wuhan is the home to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a lab that studies active coronaviruses like Sars-cov-2. That a lab leak could have been the source of this coronavirus seemed at first to a layperson at least plausible. But it was quickly swatted down when an international group of scientists published an open letter in The Lancet in February 2020 condemning, quote, conspiracy theories suggesting that Covid-19 does not have a natural origin.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Most scientists think the bats are the original source of the virus. And then it jumped to humans in a wunan wet market. [END CLIP].

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT To many, perfect coincidences would have had to take place for it to have escaped from a lab. [END CLIP].

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT There is also no reason to believe any of these conspiracy theories that it was leaked from the lab and Wuhan, whether intentionally or otherwise. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE One group, however, saw a political opportunity in the lab leak theory. It's the same group that was banging on about the China virus.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Both President Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo linked the virus to a lab in Wuhan, without providing evidence.

REPORTER Have you seen anything at this point that gives you a high degree of confidence that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was the origin of this virus?

DONALD TRUMP Yes, I have. [END CLP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thus, it became a notion embraced by the conspiratorial right, but mostly shunned by the scientific community. And scientists who did explore it, people like Alina Chen of the Broad Institute at Harvard and MIT were tarred as conspiracy theorists. That is until this month when a group of 18 prominent scientists, some of the most trusted virologists and epidemiologists studying covid-19 penned an open letter in the journal Science titled Investigate the Origins of Covid-19. Alina Chan was one of them.

ALINA CHAN Yes, I think this letter will go down in history as being the turning point when scientists – leading scientists say that we have to investigate the lab-leak hypothesis.

BROOKE GLADSTONE None of the scientists assert that the virus did, in fact leak from a lab. They merely ask for, quote, a dispassionate science based discourse on the issue. And they offer a critique of the one major WHO, quote, investigation into the origins of the virus conducted by a team of international scientists, half of whom were China based. It was the Chinese team that actually did the investigating, gathering, processing and ultimately holding onto the data to those who penned the open letter. The result was extremely unsatisfying.

ALINA CHAN This was not an investigation at all. They had no power. So all they could do was really look at the findings of the Chinese side of the team and think, is this reasonable? And then sign off on the document altogether to present it to the world, in March of this year.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The Chinese team had four different hypotheses.

ALINA CHAN So the first was a bat to human direct transmission. That a virus that was in bats jumped directly into humans. The team said that it was possible, but they didn't say it was the most likely scenario because there has been no record of such a transmission happening, at least not publicly.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What was the most likely?

ALINA CHAN There is the second scenario where a bat first gives the virus to an animal that is more similar to humans and then that animal gives it to humans, so it requires an intermediate host.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I remember the film Contagion. It came from a bat to a pig to a human.

ALINA CHAN Yeah, exactly. And in Sars-1, it was civet cats.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Mmhmm. Then there's the third scenario, the possibility of a lab leak. The Chinese team really didn't like that hypothesis.

ALINA CHAN The China, WHO team said that it was extremely unlikely, and decided not to pursue this route of investigation or study any further. Then report, it was the trigger for all scientists to say we need to speak up, say that a lab-leak hypothesis is still plausible and worth investigating.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Then there's the frozen food scenario. The Chinese team seemed to like that one.

ALINA CHAN Yes, and again, this was another hypothesis that was very surprising to a large number of scientists. There's no precedence of a virus jumping from frozen foods into humans, as far as I know. In fact, even with this many millions of people infected, there's been no proven record of someone catching sars-cov-2 from a block of frozen fish, or frozen meat. But yet the China, WHO team said that this was more likely than the lab-leak hypothesis, which actually has precedence. SARS virus itself has leaked from a lab close to 6 times.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We know that this argument isn't merely of historical interest.

ALINA CHAN We need closure. This pandemic has affected so many lives and it's killed 3.5 million people, and we need to mitigate this kind of risk. If it did come from animals, especially illegally trafficked animals, it can help us put all the weight we have against this sort of trafficking. But if it came from a lab, even if it came from well-intentioned research, then we have to start regulating that research. This is research that sends researchers into remote areas to collect mobile viruses and bring them back into densely populated cities for study. This sort of work has been pitched as pandemic predicting and preventing work, but if it actually is the source of new pandemics, then we need to have a good, hard think about how we should do this research in the future.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Just to clarify, nobody who signed this letter is saying that a lab leak did caused the pandemic, just that it warrants investigation, right?

ALINA CHAN Yes. And I think that's one challenge that has really obstructed the investigation of this hypothesis since the beginning, because anyone who raised the hypothesis of a lab leak was accused as sort of warmongering as saying that this definitely came from a lab.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That anyone who suggested there was a lab leak was spreading misinformation.

ALINA CHAN There was some scientists who came out very strong at the beginning of the pandemic, when barely anything was known about the virus, said that it's clear that this is from nature. No lab-based scenario is plausible. And these works are published in The Lancet and Nature Medicine. So, when you have that, then the rest of the scientific community and science journalists tend to fall in line. That set the tone for the rest of the discussion for the year I think.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The February 2020 letter in Lancet, the first draft of it was written by a Peter Daszak, who actually had a stake of a kind in the Wuhan lab.

ALINA CHAN Peter Daszak, he's the president of an equal health alliance, a nonprofit organization based in New York. They received millions of dollars of funding and part of that money was sent to the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Let's get back to the politics for a second. In early 2020, both China and the United States started slinging theories around that China intentionally created this virus. And then there were others who said it actually came from a lab in the United States.

ALINA CHAN Yes, I think the circumstantial evidence points away from an intentional release. As to whether there was bioweapons work – who can tell? Most of the viruses that have escaped from labs are selected from nature. They don't need to be Frankenstein Chimaira built in the lab. They don't have to be bioweapons. Nature already has a lot of good stuff, it has a lot of very scary, dangerous viruses that we can bring back into the lab and accidentally leak.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But isn't part of the problem with the resistance to looking into an accidental lab leak, the fact that it has been shuffled in with these other conspiracy theories?

ALINA CHAN Yes. And so I kind of understand why some scientists were in such a rush to condemn any idea of that leak, because they wanted to strongly shut down any conspiracy theories about bio weapons. I understand that, but I also think that they should have more publicly explained this nuance. On the last day of 2019, on the first day of 2020, when the Beijing CDC went to sample the Wuhan Market, they collected hundreds of samples from this market, including from all the animal carcasses as well as the environment. So, the surfaces, doorknobs, sewers, and there were no animal samples with this virus in it. And in fact, if you read the reports, they said that there were no live mammals in this market. So, it's a live animal market, but they were selling live frogs and reptiles and snakes. None of these are hosts of sars-cov-2 virus. There's no way for an intermediate host to be spilling over this virus into humans at that market.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Can you talk about some of the scientific misconceptions that have caused confusion around the origins of covid-19?

ALINA CHAN One major misconception is that this SARs research at the WIV was conducted in such a safe high biosafety level that it could never have leaked. All of this work was done at much less safe levels than people thought.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But there are a lot of labs doing this kind of work. Are there similar lapses in safety measures in all of them, including the US?

ALINA CHAN Yes, even labs have no reported biosafety incidents have biosafety incidents. If there are no accidents ever in the lab, that means you're not doing any experiments. And so, in the case of the first SARS virus. It escaped from a lab in Singapore, it escaped from BSL-4 in Taiwan, it escaped about 4 times from a single lab in Beijing when it was being studied back in 2004. And none of these scientists were doing anything crazy with the virus. One of them didn't even work with the virus. Somehow it had contaminated his sample, and he got sick. Another massive misconception is that the Wuhan Institute of Virology wasn't built there because it's a SARS hot zone, that is completely untrue. The strongest route by which the SARS virus could get all the way from its home in South China, more than a thousand miles into Wuhan is, in my opinion, actually dozens of lab personnel crawling into this extremely difficult to reach caves, bringing thousands of that samples back into the crowded city of Wuhan, its a very modern city.

BROOKE GLADSTONE All of this makes one think that maybe we shouldn't be doing that kind of research. And you're afraid that people will come precisely to that conclusion.

ALINA CHAN It's important for us to understand what is out there. I think it's very valuable. It's not that this research should not be done. The question is how can we make it safer? So maybe we shouldn't be doing it right smack next to the international airport. Maybe we should be doing it in a place where researchers are required to quarantine for two weeks or more between working and those locations and coming back in to where there are millions of people in the city. There are ways to make this research safer while still doing it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE All you're asking for is an investigation. In an effort to protect scientific research, has the scientific community run the risk of undermining its own credibility?

ALINA CHAN Yes, this science letter that was just published really is a call to return back to science-based discourse. For me, the mistake would be for scientists to show the public that, no, we cannot check ourselves, we can audit ourselves. Scientists need to take the leadership reviewing the research that we've been doing and saying, could this have caused a pandemic? This is a precedent setting situation. So, this is the first time there's been such a plausible scenario of overlap resulting in a pandemic. We really need to establish a protocol and a system where we can investigate no matter where the next possible, lab leak pandemic occurs. Because if we don't investigate, then we keep letting these past and we keep letting it go. We're just going to end an era of lab-based pandemics. So we just don't need every five to 10 years. A new virus escaped from a high security lab. We can't let that happen.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Alina, thank you very much.

ALINA CHAN Thanks for having me on the show.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Alina Cho is a post-doctoral researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. Coming up, how an argument over aerosols and droplets probably cost us a whole lot of lives. This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. The media, which polls suggest inspire meager trust these days, is further bedeviled when it's joined at the hip with science. Decoding research for mass consumption, clarifying a daily barrage of new statistics and putting guidelines into context is complicated, but it's further tangled up when the communication breakdown occurs among the scientists themselves. Case in point, the novel coronavirus that shut down much of the world cracked open a decades old inconsistency previously papered over in how different kinds of scientists talk about infectious disease. It didn't matter much until it really did. At the center lay one measurement: 5 microns, or 5 millionths of a meter. For the medical community, that number represents a threshold between particles that could spread an infection through the air and particles that couldn't. It was a number long enshrined in the medical literature, but utterly wrong. Megan Molteni is a science writer for STAT News and author of a recent Wired piece titled The 60 Year Old Scientific Screw Up That Helped Covid Kill. She launches her piece with Linsey Marr, an aerosol scientist at Virginia Tech, on a Zoom call with fateful consequences.

MEGAN MOLTENI Linsey Marr studies aerosol science, and she's one of the few people in the world who also studies infectious disease. And that was one of the reasons why she had been recruited to be in this group. It was about 36 aerosol scientists from around the world, and they had basically been seeing the way that covid was moving around different environments in cruise ships and in restaurants and in call centers. Based on what they knew about how aerosols move in those environments. They thought that sars-cov-2 looked like a virus that was moving through the air and not through these droplets that only land a foot or two away, as the WHO had been saying in its daily press briefings and in its materials that it put out on social media. So, they had asked for a meeting with the WHO and a number of their expert advisors to basically make a case that they thought something else was going on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And the WHO, you noted, which had readily accepted that particles of many sizes can hang aloft and travel far and be inhaled in the context of air pollution, simply couldn't extend that acceptance to airborne particles carrying viruses.

MEGAN MOLTENI For a number of the aerosol scientists on the call, this was kind of shocking to see these physics that they studied in their labs, being met with resistance from members of the medical community.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We're talking about two camps on Zoom, you wrote, that literally couldn't understand each other.

MEGAN MOLTENI Yeah, they really were having a language barrier problem. And and to understand it, you have to understand how each group defined droplets and particles and aerosols that move through the air.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Can you just tell me what the significance of that is?

MEGAN MOLTENI So the implication from an infection control standpoint is that if a disease is airborne, then you want every health care worker who's coming into contact with that patient who has that airborne disease to wear an N95 mask to prevent the smallest aerosols, and then you also want to put that patient in an isolation room so that air is not leaving that room and then recirculating around the hospital. For a droplet-based disease, you would ask the patient to put on a surgical mask to block those droplets. You just take different precautions. You're kind of really elevating things by calling something airborne.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Was there a concern by the people on that call from the WHO. that somehow the public wouldn't be able to get their minds around aerosols or that it would needlessly alarm them, something like that?

MEGAN MOLTENI It's important to remember that, you know, the WHO is a massive international body with lots of different priorities in terms of its public health goals. There was a concern that if they were to call sars-cov-2 airborne, that both it would cause a public panic, that people have not been educated to understand exactly what that means, we've all seen Contagion. There's also the concern that if they were to state that it was an airborne disease, they were basically making the recommendation to nations that they implement these N95's for health care workers, implement isolation rooms in hospitals, and these are really big dollar investments that you'd be asking of cash strapped countries that might leave them without funds to deal with things like malaria or other massive disease burdens they might also be facing. And at the time we're talking about beginning of April, the evidence suggested that, you know, it could travel through the air in certain environments, but it didn't look like a classic airborne disease. Outbreaks where it seemed to implicate aerosols were things like the choir in Skagit Valley, Washington, and the cruise ships. It's still within a contained indoor space where ventilation is poor, but it's traveling much further than a meter or two. So, it's kind of this in-between zone that the medical community didn't really have a category for

BROOKE GLADSTONE Stepping out of the interview here for a minute, dividing the two sets of specialists on the Zoom call, was a matter of lexicon and a matter of fact. Lexicon first, the medical experts saw the difference between aerosols and droplets as a matter of size. More than 5 microns, it's a droplet, it doesn't hang around in the air. And if a virus spreads by droplets, then hand washing and social distancing are good solutions. The aerosol experts defined particles not by size but in how they traveled. To them, cruise ships and choir room outbreaks suggested that covid was an airborne virus, but here the medical folks balked. To them, airborne meant not only a disease that travels by aerosols, the particles smaller than five microns, but travels far – think measles or tuberculosis. And then there was the matter of fact, Linsey Marr had to burrow deep into the medical history to locate the source, and here the aerosol experts were definitely right. And the medical experts on the call, wrong.

MEGAN MOLTENI Lindsay Mars deep dove into the history of this five micron cut off, took her back to the end of the 19th century when the idea of miasma theory that there's poisonous air and it makes you sick is going out of style because scientists have come up with germ theory and the idea that germs travel on food and in water and this is how you get sick. And that led to all of these improvements that really did reduce the infectious disease burden in a huge way, except for tuberculosis. Tuberculosis was still this public health scourge. And there was a Harvard engineer named William Firth Wells who offered an explanation for why that would be.

BROOKE GLADSTONE He did an experiment on guinea pigs.

MEGAN MOLTENI Yes, in a tuberculosis ward at a VA hospital, he pumped in air from the TB patients into this chamber that was housing guinea pigs. And they saw that in chambers that had this infected air, the guinea pigs got sick. And when they autopsied them, they saw the tuberculosis in their lungs. And then they did a controlled experiment where they used UV light to eliminate the tuberculosis bacterium in the air that was being pumped in and those guinea pigs did not get sick. And so that was the first time that there was definitive proof that the medical community would accept that airborne diseases were a thing.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The problem is, the size of particles that transmit tuberculosis is around five microns, whereas Wells determined that maybe 100 microns could be taken in from the air.

MEGAN MOLTENI The important thing to know about tuberculosis is that this bacteria only infects a certain kind of lung cell that only lives deep, deep, deep in the lungs. And so, the only time you can get infected with tuberculosis is if some of the bacteria makes it all the way into that deepest recess of your lungs. And the only way that happens is if it's carried in a particle smaller than five microns. And so it Linsey Marr's team discovered was that in the historical scientific record, you have this linkage of the five microns as being the definition by which any disease is airborne. But the problem is that tuberculosis is this kind of curious, unique critter and most respiratory viruses and bacteria aren't that picky. And so,it wound up not being a very good stand in for the whole menagerie of respiratory viruses that are out there in the world.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So would you say that this confrontation we began with in 2020, on a Zoom call, has it been resolved?

MEGAN MOLTENI In some ways, yes. Over the last year there have been some small steps that the show has taken. They changed some language last summer, they updated some ventilation guidance. A few weeks ago, the World Health Organization updated a page on its website titled: Coronavirus Disease How Is It Transmitted? Whereas before, the page had suggested that the main way the virus spreads is by droplets. The revised response now says that it may be these aerosols as well as droplets. And the CDC the next week went a little bit further and stated that, in fact, aerosols are at the top of the list for how the disease spreads.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Now that aerosols have begun to get their due, are people seeing them in the transmission of, you know, annual influenza or a variety of other illnesses where they might not have seen them before?

MEGAN MOLTENI Well, this is where Linsey Marr's research really first started. Some of her work in 2011 and 2012 showed that influenza was where people didn't expect it to be. It was it was in the aerosols. And so, there is a renewed interest in going back and looking at the evidence that we've had for this droplet dogma that has for so long reigned. I think what the past year has demonstrated to people is that aerosol science isn't just about climate change and hairspray, but, you know, it has really this whole other important application in the world of infectious diseases. The biggest shift that we're seeing right now is a movement away from this dichotomy of saying droplet versus airborne and moving towards something that recognizes that the world is a little bit fuzzier. One new classification system that's being discussed right now is to move to a more mechanistic explanation. And so instead of droplet first airborne is to say a respiratory disease is transmitted via inhalation or via touch or via sprayborne. So, like when I sneeze all over someone new, because that actually describes how that infectious particle is traveling from one body to another.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Your piece ends with a touching anecdote. Would you describe it?

MEGAN MOLTENI So anyone who knows Linsey knows what a stoic and pragmatic and just incredibly hard-working person she is. On the day the CDC changed its update earlier this month, she had heard about it in the frenzy of work and emails. And it wasn't until that evening when she was leaving her house to drive the 15 minutes to pick up her daughter from gymnastics that she was alone for the first time. She was sitting at a stoplight with her blinker on and all of a sudden she just found herself crying. This realization that all of the additional work, all the seminars and letters and meetings and pleading with the public health authorities had generated this big change that from her perspective will save lives. So, she told me last fall that she expected this recognition of the 5 micron error and the kind of subsequent changes would take a generation or take 30 years that she hoped she would live to see it. And so, for it to happen in a year, both because of the urgency of the crisis and because of the tenacious pushing that she and others did, the reckoning that this pandemic has led to will have positive consequences for public health at long outlive this pandemic.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Megan, thank you so much.

MEGAN MOLTENI Thank you, Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Megan Sultani is a science writer for Saturnus and author of a recent Wired piece titled The 60 Year Old Screw Up That Helped Covid Kill. Coming up, you think you live online now? Welcome to the multiverse. This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Much about life is maddening and confusing. It's natural to feel that we as individuals lack the agency to fix the world's woes. That's why many of us turn to the power we do have, which is to leave it all behind. Call it distraction or denialism, escapism or just plain human nature. We're prone to create and inhabit imaginary lives through books, movies, our own imaginations, or increasingly technology.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Imagine for a moment a world that has everything you could ever dream. Every kind of story you can imagine is there and open 24/7. And if you're tired of storms, it never rains there. Weather's perfect. So where is this magical place? It's the metaverse. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The Metaverse, the chosen name for the virtual reality powered successor to our current Internet has reached full on buzzword status in 2021. Some credit for the hype could go to Tim Sweeney, CEO of Epic Games, who kicked off this company's high profile antitrust lawsuit against Apple earlier this month by defining Fortnite his crown jewel as a metaverse. Fortnite is the most popular video game of all time. Gamers have logged a stunning three point eight billion cumulative days of playtime on its servers. But is it really a metaverse? In a minute, I think we'll find out what that means. Meanwhile, catchy stories of technological advancement generate headlines and big money in Silicon Valley and Wall Street. [CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Here es a recent article from Forbes. The metaverse is coming and it's a very big deal. [END CLIP].

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT It's a brave new – I can't even say world – metaverse. Brave new metaverse here with... [END CLIP].

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT JP Morgan bullish on the metaverse is potential for ads and e-commerce. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The cash grab may have just begun, but the promises and pitfalls of a three dimensional inhabitable Internet as well trod ground in science fiction.

[CLIP]

PHILIP J FRY Behold the Internet! [MUSIC PLAYS UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE [OVER CLIP] Like this Futurama episode in which our 31st century protagonists log on to the metaverse.

PHILIP J FRY My God, it's full of ads.

BROOKE GLADSTONE [OVER CLIP] Only to be literally attacked by pop ups.

LEELA Follow me!

PHILIP J FRY It's immense. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The real metaverse may be years or decades off, but Gene Park, who covers video games for The Washington Post, is watching its development with anxiety and excitement.

GENE PARK The metaverse is basically thought of as the next version of the Internet. A virtual world having its own economy where the inhabitants, Internet users would be able to kind of coexist online doing work as they would in their real life. Of course, there will be avatars and they'll be like actualized places

BROOKE GLADSTONE Like Magic Castles or Starbucks? Is this a place you would go to escape the real world or is it just another place of business?

GENE PARK Some people would want to use it as a form of escape, but I think for a real metaverse to function, it would be a place where people would go to work.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I'm still trying to get a handle on what it would look like. What would it feel like?

GENE PARK Virtual reality is probably the simplest way to kind of imagine it. That's the way that it's been. Imagine for decades stemming from the 1992 Neal Stephenson book Snow Crash. Snow Crash coined the term the Metaverse. And the most famous depiction of a metaverse would be the book and the Steven Spielberg film Ready Player One

BROOKE GLADSTONE And for those who haven't read it, can you summarize that?

GENE PARK Yeah. Ready. Player one envisions a corporation that has established the metaverse. Imagine Facebook with like 100 times more power and the main character has to find a secret of why the company was started, but within his adventures, within that metaverse, he's able to interact with so many different IP, from cartoon sports figures to books that he used to read or shows that he used to watch because they all coexist within this space. Much like Fortnite, Fortnite already has different characters in different IP from different companies, all clashing together in one existing space.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But I always thought Fortnite basically was a shooting game.

GENE PARK Fortnite has definitely evolved into more of a social networking platform in which you still shoot other characters. Right. But they've also now included features where you don't have to do any of that stuff. You can just hang out and talk and it's kind of become like the Gen Z Zoom, where people will go on Fortnite and just kind of meet and talk and sit together and watch a movie in Fortnite.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Travis Scott, the rapper, he had a 15-minute concert in April last year.

GENE PARK I would absolutely call it a Travis Scott April concert, a turning point for a fortnight at. And for its metaverse ambitions. That was the largest attempt yet at being able to kind of create like a gathering space for people and for having a reason outside the game for tens of millions of people to log on to the game,

BROOKE GLADSTONE 46 million watched it and danced along.

GENE PARK Yeah, that's quite an attendance figure for a concert. Wouldn't you think?

[CLIP]

TRAVIS SCOTT Sun is down. I'm freezing cold. That's how we already know, when it's here. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Here's the thing, I don't know how different this is from Second Life. I mean, back in the aughts, Regina Spektor performed songs from her then new album on Second Life in a virtual New York City loft. You could do all those cultural things there. You could spend money. People flirted, they even married. They built second lives there. How is this different? What makes this different?

GENE PARK Second Life is absolutely one of the first real attempts at creating something like this. The problem was, is that it definitely never attracted the millions of people it would need to kind of enter into serious conversations with metaverse. Whereas Fortnight and the other video game Roblocks, they have attracted hundreds of millions of people, and the difference between Second Life and Fortnite is that with Fortnite they were able to, you know, for lack of a better term, lure regular folks in as well as gamers, you know.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So what you're saying is that the game was the gateway drug.

GENE PARK Yes, exactly. That's a great way to put it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Also, I have to assume, you know, since Second Life was back in the aughts, that it didn't have the technology or the sense of reality that these worlds intend to employ.

GENE PARK Absolutely. Second Life looks very ancient by now. Fortnite is improving constantly, but it still doesn't have the capacity to hold massive amounts of people. We've talked about how 46 million people watch Travis Scott. Unfortunately, all of those 46 million people were divided up into rooms made of one hundred other people. Right. We're not all able to coexist in the same space. That's why the metaverse doesn't exist today. I think a lot of the reason why conversation around this metaverse, which isn't exclusively a video game concept is happening around a video game industry is because there's nothing on Facebook or Twitter, for example, that looks anything like the kinds of images that we get in video games and the kind of reality that they're able to create.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So the metaverse is being heralded as the Internet's future, but can we talk a little bit about how it's both new and old? I'm thinking more of like vision quests where instead of technology you could use a drug or a mushroom to place you in a truly different realm.

GENE PARK I see a lot of similarities between drug experiences and virtual worlds and video games, too. You know, even the Travis called concert was a very psychedelic experience. It was like a 90-foot-tall giant. As colorful explosions explode behind them. It definitely felt like a very surreal kind of drug, trippy experience.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I was thinking about the games predating the Internet that sort of enabled us to inhabit an alternate persona in an alternate world. Like live action, role playing, LARPing, or just what young kids do in every generation, whenever they're left alone.

GENE PARK Absolutely. I've once described fortnight as having the same story that I created when I was bashing two action figures together when I was six years old. You know,

BROOKE GLADSTONE it seems, though, like the metaverse will eventually feel less like a game and maybe not a world so much as a big immersive, snazzed out platform where you can buy anything you want. And that's not such a new phenomenon, why all the hype about this digital metaverse as the future of the Internet? I'm not sure what makes it a breakthrough.

GENE PARK Yeah, I think it's really hard to even envision it right now because there are so many companies having different ideas about it. Facebook, for example, invested years ago in its virtual reality platform where Oculus quests and set to launch Horizon, which is basically a virtual world to explore, play and create, as they say. And then, of course, there's epic games, and Tim Sweeney,

BROOKE GLADSTONE That's the guy behind Fortnite. Epic CEO Tim Sweeney warned that if one company ends up gaining control of the metaverse, it will become, quote, more powerful than any government and be a God on earth.

GENE PARK Facebook dominates so much of the Internet, right. Google and Facebook, it would behoove whatever company to build whatever next version of the internet might be to be in that position. So, I think there's a lot of jockeying for that position right now.

BROOKE GLADSTONE When Micah Loewinger, who's producing this two-way was talking to me about this. You know, I always loved the idea of alternate worlds. His concern was that this idea, whether darkly conceived by Philip K. Dick or Neal Stephenson or gloriously imagined, simply becomes just another way to monetize us. I want to think that there is magic out there, but whenever these big platforms get hold of it, it's just kind of ick.

GENE PARK That's kind of why I wrote that article back in April to sound a light alarm. For me, as someone who has worked for newspapers for the last 20 years, you know, I care very much about how people perceive the news. And if the media industry is about to be disrupted. Once again, newspapers are still catching up to the current reality of the Internet. Right. So, I fear for the media industry overall. And I absolutely share any fears about what this might look like and how much of it is an attempt to turn us into capital. We've had so many examples of this in recent years. I'm hoping, hoping this time that once the Internet changes again, more people will at least be a little bit ready for it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Well, thank you so much.

GENE PARK Thanks so much, Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Gene Park is a reporter at The Washington Post covering video games. From an imagined future online to a palpable one on Earth, the Future Library is inviting 100 writers, one every year to contribute to a collection that will be published in 2014. They're also growing a thousand trees for 100 years to print 3000 copies of 100 manuscripts. The Future Library also includes instructions on how to make paper. And there's a printing press again with instructions in case we forgot how to use it. So far, seven authors have contributed. The latest being Ocean Vuong. The New York Times described the project as the literary equivalent of a seed bank. Margaret Atwood was the first contributor, and when I spoke to her back in 2015, I asked if she saw the enterprise that way. That this might persist as a kind of safe haven for literature in case all else fails.

MARGARET ATWOOD Any time you write something, you're always anticipating a future reader. Even if it's your diary, you're anticipating yourself at a future point in time. Just as when you write down a musical score, you're anticipating a future player who will come along and unlock the score and turn it back into music again. A seed bank is the same idea. You put the seeds in there with the idea that somebody will in the future plant them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I'm just wondering if there was a difference writing for readers who aren't born yet,

MARGARET ATWOOD Are we talking about the idea of me maybe dying?

[BOTH LAUGH]

MARGARET ATWOOD Is that the subject here? Any book when you write it, there's always a time gap between when you write it and when somebody else reads it. It's just that the time gap is a little bit longer. Well, to be frank, quite a lot longer.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But didn't you say that readers might need a paleoanthropologists to enjoy the book?

MARGARET ATWOOD Yeah, we know how language changes over time and we know that words are appearing all the time. Words are changing their meanings all of the time. We know that we can still understand Shakespeare. Though, the further along in time we go, the more footnotes we need.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The future libraries described as a hopeful project because it's based on the belief that humans will exist 100 years from now. Is that a high bar?

MARGARET ATWOOD I don't think it's a terribly high bar, but there are a lot of other things involved, too. So, humans will exist, but will they exist, in Oslo, for instance. Trees will grow, but will they grow there? Will people be able to read? Will they wish to read? These are all things that we don't know yet, and they're going to ask for contributions from all around the globe from any language. Some of those languages may be quite small. Maybe the languages themselves will be extinct in a hundred years. And if so, should they be putting in a dictionary?

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is a question. If you got up and left right now, I wouldn't be surprised. But I'm going to ask you anyway, what do you think the world's going to be like in 100 years?

MARGARET ATWOOD Well, now the good news from the physicists is that time really does move in one direction. Things aren't all simultaneous the way they were in Slaughterhouse-Five. So choices you make now actually can influence the future. The bad news is that Donald Rumsfeld was right about one thing. It's the unknown unknowns that get you. So we don't know about the unknown unknowns. We know about some of the knowns. We know that our actions can change some of those knowns. I just read in the paper today that the cod fishery has rebounded.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That is actually very encouraging.

MARGARET ATWOOD Don't you think? Something has rebounded. We hear about all these things bounding, but we don't hear about them rebounding. So the other thing that's helpful is that there's a great endeavor underway to plan a lot of milkweed so that the monarch butterflies will rebound. And a man has discovered that one of the biggest soakers up of oil spills is actually milkweed fluff that he's making into oil spill succor. And he's got a bunch of farmers growing milkweed for this project. So people are very ingenious and they come up with all kinds of solutions.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You know, I have to admit, I'm a little taken aback by how positive you sound. Your imagined worlds are so dystopian,

MARGARET ATWOOD it's not all bad. Duct tape has survived the meltdown of the human race. It's very positive. I'm happy that there's duct tape. The thing about my books is their books, and just think of it this way, we've known her for decades to blow ourselves up with atomic bombs and we haven't done it yet.

BROOKE GLADSTONE A character in The Blind Assassin said, "why is it we want so badly to memorialize ourselves? Even while we're still alive, we wish to assert our existence like dogs peeing on fire hydrants. We monogram our linen, we carve our names on trees, we scrawl them on washroom walls. It's the same impulse. What do we hope to get from it?" And you said, or the character said, "We can't stand the idea of our own voices falling silent. Finally, like a radio running down."

MARGARET ATWOOD Is what she says true?

BROOKE GLADSTONE Is it?

MARGARET ATWOOD Is it? I'm asking you, you're the writer.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It sounds right. No one wants to die, and I guess that's the impulse for writing. But when you're staring a hundred years from now in the face, did it make a difference that you wouldn't be here a hundred years from now other than the fact that you wouldn't have to confront the critics?

MARGARET ATWOOD Young people worry a lot more than older people. And the reason they worry a lot more than older people is that they don't know the plot of their own lives yet. They don't know how it's going to turn out for them. Will they meet their true love? Will they be successful? At my age, I kind of know how the story goes. So should I get hit by a truck tomorrow? The plot will pretty much have unfolded.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And the rest of the human race?

MARGARET ATWOOD Well, of course I worry about them, but they have to worry about themselves, because it's not going to be my problem very shortly. It will, however, be theirs.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Margaret Atwood, thank you very much

MARGARET ATWOOD And thank you very much. How old are you anyway?

BROOKE GLADSTONE 60.

MARGARET ATWOOD Oh, you're a mere child.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Yeah, right!

MARGARET ATWOOD No wonder you're so worried.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Actually, less and less every day. I notice that.

MARGARET ATWOOD This is what I mean. Yeah, I could have been your babysitter and popped two into the microwave. No, I'll take that back.

BROOKE GLADSTONE They didn't have microwaves when I was that young.

MARGARET ATWOOD No they didn't, see I thought you might spot that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Margaret Atwood is the author of many, many books, her most recent novel is The Testament's, a sequel to the iconic 1985 The Handmaid's Tale.

BROOKE GLADSTONE On the Media is produced by Leah Feder, Micah Loewinger, Jon Hanrahan, Eloise Blondiau and Rebecca Clark-Callender. Xandra Ellin writes our newsletter. Our technical director is Jennifer Munsen, our engineer this week was Adriene Lily. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media, is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.