A Five-Micron Mistake

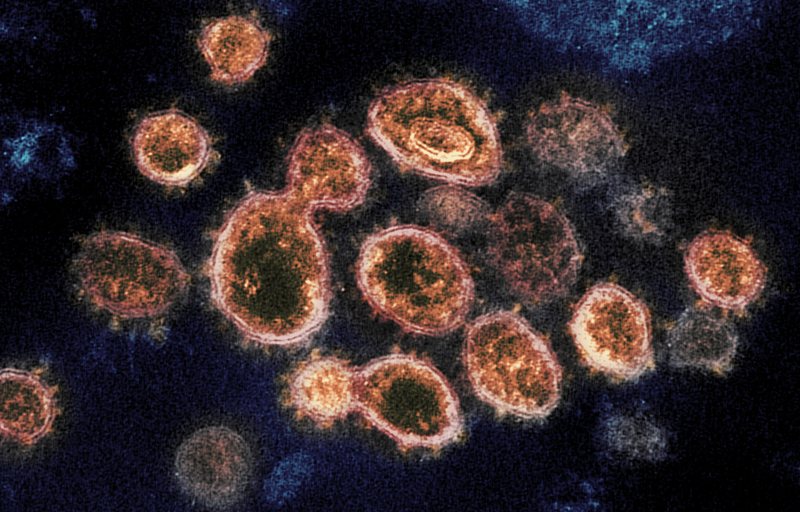

( Uncredited / AP Images )

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. The media, which polls suggest inspire meager trust these days, is further bedeviled when it's joined at the hip with science. Decoding research for mass consumption, clarifying a daily barrage of new statistics and putting guidelines into context is complicated, but it's further tangled up when the communication breakdown occurs among the scientists themselves. Case in point, the novel coronavirus that shut down much of the world cracked open a decades old inconsistency previously papered over in how different kinds of scientists talk about infectious disease. It didn't matter much until it really did. At the center lay one measurement: 5 microns, or 5 millionths of a meter. For the medical community, that number represents a threshold between particles that could spread an infection through the air and particles that couldn't. It was a number long enshrined in the medical literature, but utterly wrong. Megan Molteni is a science writer for STAT News and author of a recent Wired piece titled The 60 Year Old Scientific Screw Up That Helped Covid Kill. She launches her piece with Linsey Marr, an aerosol scientist at Virginia Tech, on a Zoom call with fateful consequences.

MEGAN MOLTENI Linsey Marr studies aerosol science, and she's one of the few people in the world who also studies infectious disease. And that was one of the reasons why she had been recruited to be in this group. It was about 36 aerosol scientists from around the world, and they had basically been seeing the way that covid was moving around different environments in cruise ships and in restaurants and in call centers. Based on what they knew about how aerosols move in those environments. They thought that sars-cov-2 looked like a virus that was moving through the air and not through these droplets that only land a foot or two away, as the WHO had been saying in its daily press briefings and in its materials that it put out on social media. So, they had asked for a meeting with the WHO and a number of their expert advisors to basically make a case that they thought something else was going on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And the WHO, you noted, which had readily accepted that particles of many sizes can hang aloft and travel far and be inhaled in the context of air pollution, simply couldn't extend that acceptance to airborne particles carrying viruses.

MEGAN MOLTENI For a number of the aerosol scientists on the call, this was kind of shocking to see these physics that they studied in their labs, being met with resistance from members of the medical community.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We're talking about two camps on Zoom, you wrote, that literally couldn't understand each other.

MEGAN MOLTENI Yeah, they really were having a language barrier problem. And and to understand it, you have to understand how each group defined droplets and particles and aerosols that move through the air.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Can you just tell me what the significance of that is?

MEGAN MOLTENI So the implication from an infection control standpoint is that if a disease is airborne, then you want every health care worker who's coming into contact with that patient who has that airborne disease to wear an N95 mask to prevent the smallest aerosols, and then you also want to put that patient in an isolation room so that air is not leaving that room and then recirculating around the hospital. For a droplet-based disease, you would ask the patient to put on a surgical mask to block those droplets. You just take different precautions. You're kind of really elevating things by calling something airborne.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Was there a concern by the people on that call from the WHO. that somehow the public wouldn't be able to get their minds around aerosols or that it would needlessly alarm them, something like that?

MEGAN MOLTENI It's important to remember that, you know, the WHO is a massive international body with lots of different priorities in terms of its public health goals. There was a concern that if they were to call sars-cov-2 airborne, that both it would cause a public panic, that people have not been educated to understand exactly what that means, we've all seen Contagion. There's also the concern that if they were to state that it was an airborne disease, they were basically making the recommendation to nations that they implement these N95's for health care workers, implement isolation rooms in hospitals, and these are really big dollar investments that you'd be asking of cash strapped countries that might leave them without funds to deal with things like malaria or other massive disease burdens they might also be facing. And at the time we're talking about beginning of April, the evidence suggested that, you know, it could travel through the air in certain environments, but it didn't look like a classic airborne disease. Outbreaks where it seemed to implicate aerosols were things like the choir in Skagit Valley, Washington, and the cruise ships. It's still within a contained indoor space where ventilation is poor, but it's traveling much further than a meter or two. So, it's kind of this in-between zone that the medical community didn't really have a category for

BROOKE GLADSTONE Stepping out of the interview here for a minute, dividing the two sets of specialists on the Zoom call, was a matter of lexicon and a matter of fact. Lexicon first, the medical experts saw the difference between aerosols and droplets as a matter of size. More than 5 microns, it's a droplet, it doesn't hang around in the air. And if a virus spreads by droplets, then hand washing and social distancing are good solutions. The aerosol experts defined particles not by size but in how they traveled. To them, cruise ships and choir room outbreaks suggested that covid was an airborne virus, but here the medical folks balked. To them, airborne meant not only a disease that travels by aerosols, the particles smaller than five microns, but travels far – think measles or tuberculosis. And then there was the matter of fact, Linsey Marr had to burrow deep into the medical history to locate the source, and here the aerosol experts were definitely right. And the medical experts on the call, wrong.

MEGAN MOLTENI Lindsay Mars deep dove into the history of this five micron cut off, took her back to the end of the 19th century when the idea of miasma theory that there's poisonous air and it makes you sick is going out of style because scientists have come up with germ theory and the idea that germs travel on food and in water and this is how you get sick. And that led to all of these improvements that really did reduce the infectious disease burden in a huge way, except for tuberculosis. Tuberculosis was still this public health scourge. And there was a Harvard engineer named William Firth Wells who offered an explanation for why that would be.

BROOKE GLADSTONE He did an experiment on guinea pigs.

MEGAN MOLTENI Yes, in a tuberculosis ward at a VA hospital, he pumped in air from the TB patients into this chamber that was housing guinea pigs. And they saw that in chambers that had this infected air, the guinea pigs got sick. And when they autopsied them, they saw the tuberculosis in their lungs. And then they did a controlled experiment where they used UV light to eliminate the tuberculosis bacterium in the air that was being pumped in and those guinea pigs did not get sick. And so that was the first time that there was definitive proof that the medical community would accept that airborne diseases were a thing.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The problem is, the size of particles that transmit tuberculosis is around five microns, whereas Wells determined that maybe 100 microns could be taken in from the air.

MEGAN MOLTENI The important thing to know about tuberculosis is that this bacteria only infects a certain kind of lung cell that only lives deep, deep, deep in the lungs. And so, the only time you can get infected with tuberculosis is if some of the bacteria makes it all the way into that deepest recess of your lungs. And the only way that happens is if it's carried in a particle smaller than five microns. And so it Linsey Marr's team discovered was that in the historical scientific record, you have this linkage of the five microns as being the definition by which any disease is airborne. But the problem is that tuberculosis is this kind of curious, unique critter and most respiratory viruses and bacteria aren't that picky. And so,it wound up not being a very good stand in for the whole menagerie of respiratory viruses that are out there in the world.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So would you say that this confrontation we began with in 2020, on a Zoom call, has it been resolved?

MEGAN MOLTENI In some ways, yes. Over the last year there have been some small steps that the WHO has taken. They changed some language last summer, they updated some ventilation guidance. A few weeks ago, the World Health Organization updated a page on its website titled: Coronavirus Disease How Is It Transmitted? Whereas before, the page had suggested that the main way the virus spreads is by droplets. The revised response now says that it may be these aerosols as well as droplets. And the CDC the next week went a little bit further and stated that, in fact, aerosols are at the top of the list for how the disease spreads.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Now that aerosols have begun to get their due, are people seeing them in the transmission of, you know, annual influenza or a variety of other illnesses where they might not have seen them before?

MEGAN MOLTENI Well, this is where Linsey Marr's research really first started. Some of her work in 2011 and 2012 showed that influenza was where people didn't expect it to be. It was it was in the aerosols. And so, there is a renewed interest in going back and looking at the evidence that we've had for this droplet dogma that has for so long reigned. I think what the past year has demonstrated to people is that aerosol science isn't just about climate change and hairspray, but, you know, it has really this whole other important application in the world of infectious diseases. The biggest shift that we're seeing right now is a movement away from this dichotomy of saying droplet versus airborne and moving towards something that recognizes that the world is a little bit fuzzier. One new classification system that's being discussed right now is to move to a more mechanistic explanation. And so instead of droplet first airborne is to say a respiratory disease is transmitted via inhalation or via touch or via sprayborne. So, like when I sneeze all over someone new, because that actually describes how that infectious particle is traveling from one body to another.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Your piece ends with a touching anecdote. Would you describe it?

MEGAN MOLTENI So anyone who knows Linsey knows what a stoic and pragmatic and just incredibly hard-working person she is. On the day the CDC changed its update earlier this month, she had heard about it in the frenzy of work and emails. And it wasn't until that evening when she was leaving her house to drive the 15 minutes to pick up her daughter from gymnastics that she was alone for the first time. She was sitting at a stoplight with her blinker on and all of a sudden she just found herself crying. This realization that all of the additional work, all the seminars and letters and meetings and pleading with the public health authorities had generated this big change that from her perspective will save lives. So, she told me last fall that she expected this recognition of the 5 micron error and the kind of subsequent changes would take a generation or take 30 years that she hoped she would live to see it. And so, for it to happen in a year, both because of the urgency of the crisis and because of the tenacious pushing that she and others did, the reckoning that this pandemic has led to will have positive consequences for public health at long outlive this pandemic.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Megan, thank you so much.

MEGAN MOLTENI Thank you, Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Megan Molteni is a science writer for STAT news, and author of a recent Wired piece titled The 60 Year Old Screw Up That Helped Covid Kill. Coming up, you think you live online now? Welcome to the multiverse. This is On the Media.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.