Manafort, Inc.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: [OVER TRAIN SOUNDS] You can hear a train in the background because —

ILYA MARRITZ: Yes. I love that.

BERNSTEIN: Alright.

MARRITZ: Okay. Andrea, you're there. Frank, you’re there?

FRANKLIN FOER: I’m here.

BERNSTEIN: We’re here. We’re in the Westin Hotel, Courthouse Square, where occasionally you can hear a train going by in the background.

[PLUCKY STRING MUSIC PLAYS]

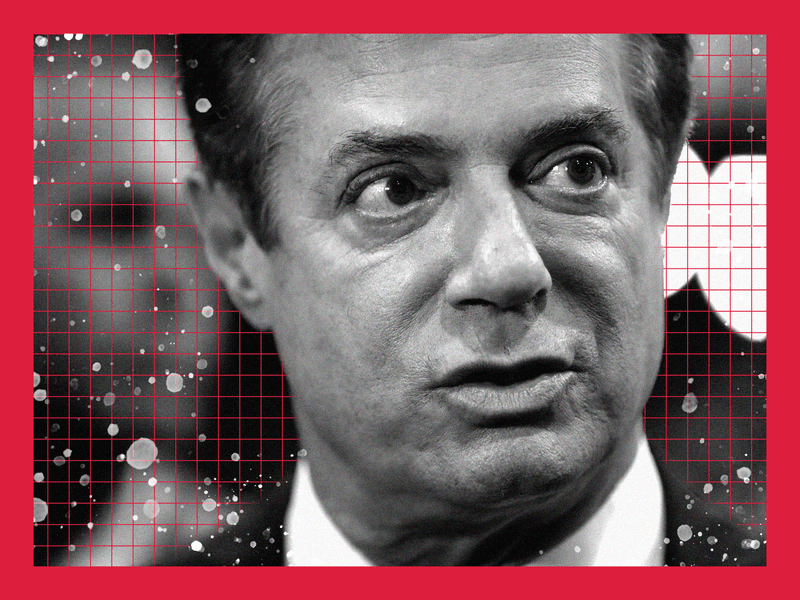

MARRITZ: Hi everyone. It's Ilya Marritz from WNYC with a Trump, Inc. podcast extra. Trump, Inc., from WNYC and ProPublica, is an open investigation into the business ties behind the Trump administration, but let's call this conversation “Manafort, Inc.” Paul Manafort was Donald Trump's campaign chairman for three critical months in 2016, including the Republican convention. For a decade before that he did political work in Ukraine, including the successful presidential campaign of Viktor Yanukovych before that man was toppled from power.

[THEME MUSIC UP]

MARRITZ: And it's the money Manafort made from that work that is now under the microscope in a Virginia courtroom, where Manafort is accused of tax fraud, hiding cash in offshore accounts, and also bank fraud — lying on loan applications. This trial is getting a lot of coverage. There are plenty of places you can go for minute-by-minute updates. What we're going to do now is look at the big picture: How did Paul Manafort make himself so valuable to the Ukrainians? Who was he to Donald Trump? And how does this trial add to our understanding of Robert Mueller's Russia investigation?

[THEME MUSIC OUT]

MARRITZ: With me now, Andrea Bernstein, my cohost and my co-reporter when we at WNYC started looking at Manafort's perplexing New York real estate deals all the way back in the spring of 2017. Hi, Andrea.

BERNSTEIN: Hey Ilya!

MARRITZ: And also Franklin Foer, a staff writer at The Atlantic. I'm a huge admirer of your reporting on Paul Manafort. Welcome to Trump, Inc.

FOER: Thank you so much.

MARRITZ: And, people, there is no better account of Manafort's life and what it all means than this piece that Frank wrote in The Atlantic titled “The Plot Against America.” We're going to post that link on our website.

So this trial opened ridiculously fast. There’s jury selection, opening arguments, and the first witness all in a day. Andrea, what's the story prosecutors are telling, and what's the story that Manafort's defense team is telling?

BERNSTEIN: So the prosecution story is known to us that Paul Manafort repeatedly lied to banks, to the IRS, in order to avoid paying taxes on his $60 million in Ukrainian income, and to maintain his lavish lifestyle after his Ukrainian client was booted out of office. And that that continued all the way up until 2017. So that's the case against Paul Manafort. Couple interesting details, like he spent $15,000 on an ostrich jacket, whatever that is. [BEAT] I was really interested to hear the defense argument, because we haven't really heard it before.

And what they were saying, essentially, is that there's nothing wrong with being rich and successful and working abroad. And if anything untoward happened here, it was the fault of Rick Gates, who was Trump's deputy campaign manager, who was Manafort's business associate for at least a decade. They said Rick Gates was embezzling, and hiding it from Paul Manafort. So their defense is, “This wasn't Paul Manafort. Maybe he didn't check a box on his tax forms. It was the people who work for him, who let him down.”

MARRITZ: And Frank, you’ve written extensively on Manafort's long history in Ukraine and Rick Gates was there with him for most, if not all, of that history. Is that an argument that makes some kind of sense?

FOER: No way, no how. I mean, Rick Gates was like a son to Manafort. Manafort’s operation shrunk over time. As he became more isolated in Kiev, as his business became more concentrated, it essentially reduced to two people, um, in addition to himself, and Rick Gates was one of them.

And Rick Gates was the guy who was running a lot of his business operations, but the email chain between the two of them is going to be so extensive, and I can't imagine that they're not clear instructions buried within that long email chain that would disprove the defense's theory of the case, but it's what they got. They're not working with a whole lot of material.

[MUSICAL FLOURISH PLAYS]

FOER: You know, it’s — it's plausible that Gates was an intermediary in a lot of, uh, the payments that happened. But, in order to get the sizable payments, it's not like you could have your flunky go to the presidential palace and beg the oligarchs for money.

What would happen is that Manafort himself would have to go to the president’s chief of staff and bill him. And the reason that these fees are so high is that Manafort was a master of overcharging, and asking for the audacious sum. And so, that's not a Rick Gates thing. It’s totally a Paul Manafort thing.

MARRITZ: I mean, you say he's the master of over-asking, which makes me think of sort of — I think if there was a headline that came out of the — the first day, it was the ostrich jacket, which I'm trying to imagine. I don't know if it has plumes or it's just ostrich skin. What do you think is the significance of all of the expensive things that Manafort bought for himself and his family? Whether it's Yankee tickets or expensive homes or $100,000 suits. I know it's good for headlines, but does it matter in other ways?

FOER: It does because his life was a Ponzi scheme. I mean, it's really hard to imagine how a guy who was — who had $60 million and his offshore bank accounts would end up underwater. But Paul Manafort just engaged in the most conspicuous consumption. And so, as money flowed in, he was finding all sorts of new, inventive ways to spend it. And he just became over-leveraged. And, in order to fuel that type of lifestyle, his life was built around this Rube Goldberg financial contraption, where the money was sitting in these offshore accounts which weren't really easy to access. In order to get money into the country, he needed to buy real estate, because that's how you get around anti-money-laundering laws. In order to have the cash to do the things that he wanted to do, he had to take out loans against those properties. And so it became this — this vicious cycle that led him to take risks that were ultimately — as we're coming to see — untenable.

BERNSTEIN: And this was a theme of the prosecution's opener — opening arguments, that Manafort believed no rules, no laws applied to him.

[KEYBOARD MUSICAL FLOURISH PLAYS]

MARRITZ: I want to ask each of you, like, what do you think is the most significant or interesting new information on the public record?

BERNSTEIN: So the thing that has really fascinated me from some of the pretrial documents, and also what we heard in opening arguments, has been the direct line in payment from the oligarchs in Ukraine to Manafort. So just want to unpack this a second.

[MUSICAL FLOURISH BECOMES BACKGROUND MUSIC]

BERNSTEIN: In 2005, when Manafort first starts having discussions with people in Ukraine about going to work there on campaigns, there has been a big national discussion about denationalization of the steel mills. The steel mills have gone into private hands, and people are making a lot of money, and Ukrainians are upset about it. It's an issue in the election. And then the people who have made money from that — and in particular, we saw a memo from an oligarch named Rinat Akhmetov — he reaches out to Manafort, and Manafort sends a memo, which is now in the court filings, and it — we expect it to be introduced into trial — in which Manafort speaks directly to this oligarch about the obstacles facing the oligarch’s favored political party, the Party of Regions.

[MUSIC OUT]

MARRITZ: It’s totally fascinating. He basically says, “You guys lost this last election. This sort of sucks for you. Here is how to get your team back in if you want to be winning again.”

BERNSTEIN: Right. So people made a lot of money from privatization. It was unpopular, and they wanted to hire Paul Manafort to make sure their guy would stay in power so they could keep making money. It’s as if that head of Exxon directly hired the political consultant because the President of the United States was voting in tax situations that were unfavorable to fossil fuel.

FOER: It's — it’s — it’s — it's actually even worse than that because these guys were gangsters who actually blew up political opponents, allegedly. [LAUGHS] Um, and that's the way that they were able to privatize these industries, that you had these vicious war for the resources of the post-Soviet …

BERNSTEIN: There was an actual conflict.

FOER: It was — it — it was actually — it was actual gang warfare, was the way in which these guys procured their nationalized properties. And so, when there was a revolution and the revolutionaries came in and said, you know, “We want things to be done the right way.” They needed to defend themselves against arrest. They needed to protect their steel mills, and the way they did that was politically. And they were kind of flailing until Paul Manafort came on the scene. In fact, when Manafort came on, the oligarch you're talking about had to relocate to Vienna because it wasn't safe for him to be in Ukraine. And he was dividing his time between Monaco and Vienna, and Manafort was advising him to take all of his operations into Austria in order to create a shadow operation in case this nationalization actually happened. And a lot of the meetings that Manafort was conducting with these oligarchs had to take place in Moscow because it was unsafe, they felt like, to conduct them in Kiev.

MARRITZ: This main oligarch you're talking about is Rinat Akhmetov, who has a big industrial base in the east of Ukraine. That's right?

FOER: That’s correct.

[TRON-ESQUE MUSIC PLAYS]

MARRITZ: And one of the things that I found so interesting about that memo to Akhmetov as well — it’s from 2009. And, on one point in particular, Manafort really surprised me. He said, “You have to dump the head of the party, Viktor Yanukovych. Ukrainians don't like him. He's too toxic.”

Akhmetov must have felt differently. He didn't take that advice, because the following year, Paul Manafort helps Viktor Yanukovych, in fact, to be elected President of Ukraine. And for the next four years, until he's toppled from power, he is Manafort's big client. And so, Frank, I want to put to you the same question that Andrea answered, which is, what do you think is the most significant piece of new evidence or information that's come to light in this case in the last few weeks?

[MUSIC OUT]

FOER: So there's this storyline about a banker in Chicago called Steve Calk, and Calk owned a very small bank and Manafort had applied for a loan from Calk’s bank, and the loan officers at the bank were like, “You know what? This guy's record — Manafort’s records are so dodgy. There's no way we can give this guy a loan.”

And then, in early August of 2016, Steve Calk ends up as one of 13 official economic advisors to the Trump campaign — a pretty cush job.

MARRITZ: Fancy that!

FOER: And so, as it's evolved, and as we've learned more from the Mueller team, it turns out that there was a quid pro quo, where Manafort said, “You know what? I can get you this job on the Trump campaign if you give me these loans.”

[MUSIC PLAYS]

FOER: And, uh, one thing that is incredibly suspicious is that Manafort is fired on August 19th, 2016. And the same day he registers an LLC called Summer Breeze. And, over time, the loans just start flowing to Manafort. 16 billion —

MARRITZ: From that bank?

FOER: And other banks too, which is suspicious. And I wonder if, uh, if that'll come up at a certain point, or if this is something that maybe Mueller's keeping in reserve, and there's another case that could be built that doesn’t necessarily implicate Manafort, but implicates others. So he resigns. The money — $16 million starts flowing to him. And it should be said that that $16 million represents 22% of the equity capital in Calk’s bank.

[MUSIC OUT]

MARRITZ: That’s astonishing.

FOER: So 22% of the equity capital and I think is going to a guy whose loan application his bank was going to reject because his history was so dodgy.

And Calk seems to have thought that he had a job in the Trump administration lined up because of this relationship to Manafort. And so, I just happen to think that that is kind of one of the most obviously, on its face, dirty transactions that we've come up across in the course of the entire Trump campaign history.

BERNSTEIN: You know, I think it’s interesting to think about the story about Steve Calk and connection of — so, Paul Manafort is in Ukraine, getting paid by oligarchs to install a government that's in their interest. And that his next campaign job is in the Trump campaign. I mean, he — according to the prosecutors — spent much of the time in the last decade before he came back to the U.S., in Ukraine — 150 days a year, they said, sleeping at the Hyatt Hotel in Kiev.

So they're making the case that he was really, really ingrained in that culture. And that all happened right before he came back to work on the campaign, which I think is just something worth keeping in mind.

MARRITZ: Yeah, I think you're sort of saying, like, the Ukrainian political culture — let’s say — it rubbed off on Paul Manafort [CHUCKLES] a little bit in those 10 years.

BERNSTEIN: There’s a whiff of that.

MARRITZ: I — you know, another thing that's interesting to me is, there's just like a slew of names in the exhibits that have been surfaced so far from these, like, 10 years of work that Paul Manafort was doing in Ukraine. And one of those names is this guy, Bobby Peed. I don't know if he's a big deal, but he works in the White House now. He’s, like, an advanced planner.

And I was Googling a couple of the other names that I saw CC'd on emails. And there's another guy who worked on the Trump campaign. And so, potentially, there might be new characters and new connections to be made that just haven't been made until this point.

FOER: I’m a little bit — I mean, having, um, fished in these waters for a long time, I'd be somewhat skeptical that those kind of bit players end up becoming bigger, just knowing the way that the Manafort operation worked and was so tightly held, which is why the claim that he was ignorant of everything is kind of laughable to me, that Manafort was a micromanager who kind of buried himself in his work.

And so, uh, you know, one other name [LAUGHS] who’s dangling on the fringes, who's indicted by Mueller, is this guy called Konstantin Kilimnik, who was in Manafort's orbit. He had two right-hand men. There was Gates — Rick Gates — and there was Konstantin Kilimnik, who was Ukrainian-born, had Russian citizenship, who trained at a Russian military intelligence language school, and then gets hired by Manafort. And —

BERNSTEIN: Okay, just pause on that.

FOER: Yeah.

BERNSTEIN: Russian military intelligence language school is usually — or is frequently — interpreted by U.S. intelligence to mean he was trained as — to spy.

FOER: Exactly. And so there were — throughout his career, there were hints that Kilimnik was actively working for Russian intelligence. And, in fact, Robert Mueller, in various filings, has baldly asserted that Manafort's right-hand guy was an active agent of Russian intelligence. So what does that mean? Where is that going? How does that fit into any of this? I don't think that's any clearer today than it was yesterday.

MARRITZ: Yeah, I suppose with someone like Kilimnik, it — [LAUGHS] that really illustrates how Robert Mueller must really wish that Paul Manafort was cooperating right now, rather than bringing this to trial. Because think of the information that Manafort potentially could surface about a figure like Kilimnik. Um, do you — either of you guys know, does Manafort — does he have character witnesses lined up?

BERNSTEIN: We haven't heard his witness list yet. And typically the defense doesn’t firmly decide until the prosecution has put on their case. He may not put on any witnesses, and he is not required to, if they feel like they've sufficiently discredited the government's case.

MARRITZ: Frank, if he had to ask somebody, who would he ask?

FOER: You know, that's a re— it's a surprisingly tough question. And when I've reported on Paul Manafort in the past, you usually can turn to kind of a handful of courtiers, who, you'd say, “Alright, these guys are going to be great witnesses, character witnesses. They'll say anything on this guy's behalf.” And that's always been a bit of a problem with Manafort, is that his universe shrunk. When he went to Kiev, he kind of cut himself off from a lot of his old political friends in Washington — people he grew up with.

You can't really put his old comrade, his old partner, Roger Stone [LAUGHS] on the stand because he has his own problems. And he's kind of in the hot seat with Robert Mueller. Gates would have been a character witness, but he's flipped on Manafort. And then a lot of people I know who know Manafort well kind of say, “You know, he's a great guy, but I can't say he didn't do this.”

MARRITZ: Right. Anybody who knows him and his work well kinda knows, I guess, that he specialized in working with some pretty unsavory characters, actually, in helping to make them politically palatable. That was kind of his business. So I guess if you knew him in a business context, that's what you knew him to do.

FOER: Right. And you knew that he was a guy who, as the def— the prosecution described yesterday, acts with impunity. That's been his style. It's his swagger. It's a source of his business acumen, is that he's always been willing to push the envelope.

MARRITZ: Andrea was Manafort's family in the courtroom yesterday?

BERNSTEIN: Uh, his wife, Kathleen, was there and a friend of hers. Uh, they were wearing black.

FOER: Uh, just knowing Paul Manafort, I bet her choice of dress was directed by Paul Manafort, because that's the type of thing he thinks about.

BERNSTEIN: Why do you think he didn't wear socks?

FOER: Because that's also part of his shtick, is that he was, like, the guy in Washington who didn't wear socks, because when he was in Cannes or Nice or wherever, that's what the jet-set does.

MARRITZ: How do you think this trial is looking for the occupant of the White House right now. How do you think Donald Trump is watching this trial at this moment?

BERNSTEIN: This trial does appear to be centering tightly on the evidence of bank fraud and tax fraud. That's what the prosecution has to prove. That — doing that — and we've seen their exhibit list — does not depend on bringing in the Trump presidency in any way. So, if you're Donald Trump, maybe you are thinking, “Okay, this is a man who committed tax fraud. This is a man who committed bank fraud. What does it have to do with me?”

[CREDITS MUSIC PLAYS]

BERNSTEIN: Now, this is a theme that we've seen an awful lot in people that have been Donald Trump's business partners.

And in a sense, that's what Manafort was doing. He was running his campaign at this crucial period when the Russians started to hack, and started to release this hacking, and started to make attempts to reach out to the Trump campaign. Paul Manafort had a high-level position and-or was in charge.

MARRITZ: Not only was Paul Manafort in charge of the campaign at a really critical moment, we are now beginning to really see in great detail how much pressure he was feeling financially, and how much debt he was in. But we have to leave it there with Franklin Foer, a staff writer at The Atlantic, and Andrea Bernstein, cohost of this podcast, Trump, Inc. Thank you both very much.

BERNSTEIN: Thanks, Ilya. Great talking to you.

FOER: Pleasure.

[CREDITS MUSIC PLAYS UP]

MARRITZ: Trump, Inc is produced by WNYC and ProPublica. We're coming back for a second season in September. Until then, please watch your feed for these podcast extras. Engineering this week was by Giuliana Fonda and Phil Moss. The editors are Charlie Herman and Nick Varchevar. Jim Schachter is the Vice President for News at WNYC. Steve Engelberg as the Editor-in-Chief of ProPublica. Original music by Hannis Brown.

[MUSIC OUT]

Copyright © 2018 ProPublica and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.