The Sound of America

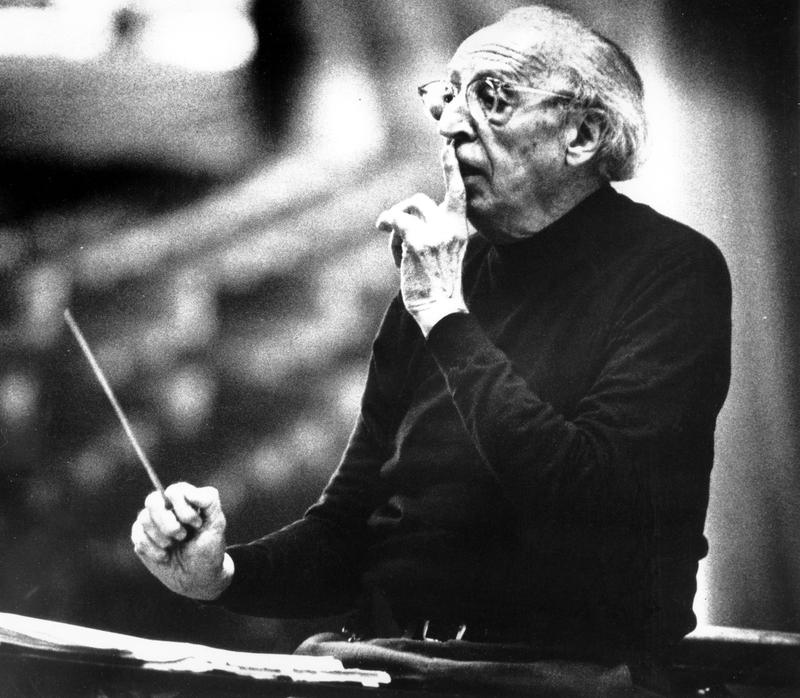

( AP / AP Images )

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield. There are many Americas. Nowadays, they barely speak to each other. But during the most perilous years of the last century, one young composer went in search of a sound that melded many of its strains into something singular and new. He was a man of the left, though of no political party, gay, but neither closeted nor out, Jewish, but agnostic, unless you count music as a religion. On this July 4th weekend, WNYC's Sara Fishko tells his story.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

SARA FISHKO: The Aaron Copland story is filled with irony. For one thing, Copland reached the height of his artistry and fame during the most desperate times in 20th-century America, the era of the Great Depression and the years of World War II. And for another, he first thought about creating music that sounded uniquely American only after he had left America, Brooklyn, to be exact, for Europe in 1921. He recalled later he had read about an American music school being formed that very year, post-World War I, outside Paris.

AARON COPLAND: The instant I read about it, I thought, oh, gee, I don’t know a soul in France. This would be a way of going and at least having some friends around and getting a, a start.

SARA FISHKO: So off he went. Once there, Copland began to search for a compositional style –

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

- in his own way, says Judith Tick who co-wrote Aaron Copland’s America.

JUDITH TICK: He graduated high school and did not go to college. Instead, he became an apprentice.

SARA FISHKO: His mentor in Paris was the famed Nadia Boulanger who would go on to train everyone, from Quincy Jones to Philip Glass.

JUDITH TICK: He absolutely adored the milieu that Nadia Boulanger created around her, which was premised on the notion that a composer had to find his own voice.

SARA FISHKO: And for a while, looking for his own voice, he lived the Paris life, that lost-generation life we know a little bit about from Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, artists and thinkers looking for new forms, new ideas. Copland used to wander over to Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company bookshop on the rue de l'Odéon.

AARON COPLAND: One would see Joyce there every evening and André Gide go across the street for French books. I really lived through this whole sense of getting rid of the past and developing something new of our own time.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

SARA FISHKO: As it turned out, Copland's teacher pushed him toward the new American jazz and, for the first time, it excited him.

AARON COPLAND: The great charm of jazz hit me – from 3,000 miles away [LAUGHS], you might say. In Paris it seemed much more American.

SARA FISHKO: He wrote this piece, “Jazzy” around that time.

[“JAZZY”]

For him, jazz was the catalyst. It forced him to ask, what would be a way to write concert music that sounded American? After all, pretty much every other country had its own distinctive classical music, said Copland, later to a group of college students.

AARON COPLAND: The ‘20s was the period of Bartók writing specifically Hungarian music. Stravinsky was very Russian. He couldn't possibly have been anything else. Debussy was terribly French. And -

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER]

- so that –

[COPLAND SPEAKING, UP & UNDER]

SARA FISHKO: It seemed only right for America’s music to have a recognizable character too.

JUDITH TICK: And he came back to New York determined to write American music.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

SARA FISHKO: Back in the US, he hadn’t solved it, yet. Author Paula Musegades says he was still writing as a post-World War I modernist, in a very individualistic style.

PAULA MUSEGADES: The music is more atonal. It’s a stark difference from the more Americana sound that you tend to associate with Copland.

SARA FISHKO: And it wasn’t very popular. He and the world kissed modernism goodbye in the next decade.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

PAULA MUSEGADES: When the 1930s hit, modernism crashed as sharply as the stock market did in 1929.

[CLIPS]:

ANNOUNCER: Ladies and gentlemen, the president of the United States.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUSE]

PRESIDENT FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT: My friends, I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking.

[ROOSEVELT’S WORDS UP & UNDER]

SARA FISHKO: Copland, along with millions of Americans, heard President Franklin Roosevelt broadcast his first Fireside Chat during the Great Depression.

PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT: We have provided the machinery to restore our financial system and it is up to you to support and make it work.

[PRESIDENT’S SPEECH UP & UNDER]

SARA FISHKO: It was in these years that FDR created the New Deal and said to the American people, we are all in this.

PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT: - together we cannot fail.

[END CLIP]

SARA FISHKO: And the spirit of liberalism rose in the country. Americans trying to recover from the crash united around progressive ideas.

SAM TANENHAUS: Roosevelt's victories in 1932 and especially in 1936 were gigantic.

SARA FISHKO: Writer and historian, Sam Tanenhaus.

SAM TANENHAUS: Democrats had majorities of a kind that are almost inconceivable today. This was not an era like our own of divided government. This was the Democratic Party forming coalitions with liberal Republicans.

SARA FISHKO: There was not only room for artists in the society, it actually presented them with a new civic identity and responsibility.

PAULA MUSEGADES: The federal government was funding programs for artists, including writers, poets, performers and composers.

SARA FISHKO: Copland jumped right in. He was active in the Young Composers’ Group, the Composers’ Collective and, in 1937, he cofounded the American Composers Alliance. This was growing into the broadest left-wing culture America has ever known.

JON WIENER: They called IT the “Popular Front.”

SARA FISHKO: Jon Wiener teaches history at UC Irvine. He says it was a movement, antifascist, pro-union, civil libertarian. Believe it or not, for a time the slogan of the Popular Front was “Communism is 20th-Century Americanism.”

JON WIENER: They wanted to be good Americans. They believed in American ideals. For them, there was no conflict between being a leftist and being a, a good American, believing in equality and freedom of speech.

SARA FISHKO: Artists like Copland were captivated by the sense that they could build nothing short of a new kind of United States. Social Security was created. Unions gained the right to strike. And the idea emerged that “the common man,” a key phrase of the moment, could achieve just about anything.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

JON WIENER: Culturally, a new idea of America was being formed in two places in particular, through jazz, which was multiracial. It was dominated by African American musicians with some great white musicians and even some integrated bands, like Ben Goodman’s, and Hollywood. Hollywood was the creation of immigrant Jews [LAUGHS], for the most part, who came up with this idea of an ideal America. So the notion of what the utopian American culture could be was coming from a much wider stream of sources than it ever had before. That’s the beginning of mass culture in America - movies, music, comic strips, the radio.

SARA FISHKO: To see the merging of traditional American patriotism with the spirit of the New Deal and with a little of the common man thrown in, you had only to go to a Frank Capra film. Thomas Doherty, author of Projections of War, prefers Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

THOMAS DOHERTY: Which really comes at a time in which America is looking at what will probably be a second world war.

[CLIP]:

JEAN ARTHUR AS CLARISSA SAUNDERS: …what do you think? Daniel Boone's lost.

THOMAS DOHERTY: That montage of Jimmy Stewart as Jefferson Smith.

CLARISSA SAUNDERS: Lost in the wilds of Washington.

[END CLIP]

THOMAS DOHERTY: - taking the tour of Washington when he first comes to town, can still bring tears to even a cynical American eye when he, you know, goes through all the, the great secular cathedrals of American life, ending at the Lincoln Memorial.

SARA FISHKO: Which brings us back to Aaron Copland, who was as swept up as anyone in the urgent collective spirit of the moment in the 1930s. It was thrilling.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

PAULA MUSEGADES: I think you can look at the 1930s as the beginning of a renaissance of awareness about American folk music.

ALAN LOMAX, SINGING:

As I was out walkin' an' a-ramblin' one day,

I spied a fair couple…

[SINGING UP & UNDER]

PAULA MUSEGADES: And Alan Lomax is a key figure in any understanding of what Copland was about. He was such a radical collector of Anglo-American and African-American folk music at a time when people really didn't understand what this was.

ALAN LOMAX, SINGING:

And the other was a cowboy, an' a brave one was he.

PAULA MUSEGADES: Copland knew Lomax. He used to go over to his house and listen to music. Copland soaked up the tunes.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

Lomax lived his life in the field. He lived his life in a truck, weighted down with tape recorders and tape machines and he went to prison and flood islands and remote places and recorded people. Copland took what he needed wherever he could get. It found its way to his musical consciousness because it was so much in the environment.

SARA FISHKO: By the late ‘30s, Copland’s piece, “Billy the Kid” was filled with spare open chords and folk-inspired melodies. [MUSIC] The composer had arrived at what turned out to be a signature sound. [MUSIC]

QUESTION: Where do you place him in the use of this sound with these relatively unusual intervals for that time.

JOHN CORIGLIANO: I place him at the top of that.

SARA FISHKO: I’m sitting opposite composer John Corigliano who is at the piano.

JOHN CORIGLIANO: He may not have been the very first but he was certainly the one that is most recognized. When that sound comes - and it’s called Americana, by the way.

[MUSIC]

SARA FISHKO: What was he using to create that sound?

JOHN CORIGLIANO: Well, Aaron Copland wanted to preserve the sense of tonality, the sense of being in a key. The chords that came out of those scales were chords that had been used for 200 years, and he wanted to make fresh chords that still could be in a key. And to just illustrate…

SARA FISHKO: Tonal composers had, for the most part, made chords built around conventional thirds, that is, built around every other note in the basic scale.

[CORIGLIANOA PLAYING A SCALE ON PIANO]

JOHN CORIGLIANO: We have a chord. Chords harmonize. [PLAYS THREE CHORDS] What Copland did was he decided that you didn't have to build chords on every other note. You could do other ways of combining notes to make a sound like a chord. For example, you can use just one note above the - [PLAYING] and you can get a beautiful sound if you play that [PLAYS CHORDS]. Copland used very often two-note chords, and when he had more than two notes they were very far apart or very close together, but they didn't have this chain of thirds, so they sounded very sparse, and yet, sounded very beautiful.

[MUSIC]

SARA FISHKO: So there it was, a non-European, somewhat radical, very accessible American style, tender and yet triumphant, simplified to go along with the progressive populist politics that had led Copland in this direction, in the first place. And it was patriotic, in keeping with a moment that celebrated the so-called “common man.”

Next stop, Hollywood, to write the score for the film, Of Mice and Men.

[SCORE PLAYING[

Aaron Copland was now a celebrity and he was a gay Jewish celebrity, at that. He was greatly admired by other American composers and had public acceptance, as well. By the time of World War II, he was one of a group of leading American composers asked to contribute an orchestral fanfare to the war effort. It was the conductor Eugene Goossens of the Cincinnati Symphony who put out the call, and Copland set to work on a short piece, something that might rally support and spirit.

As the fanfare began to take shape, the war was on the minds of the country’s leaders and citizens, says Harvey J. Kaye, author of The Fight for the Four Freedoms. It was hard, if not impossible, to think of anything else. And that had been true for the last few years.

HARVEY J. KAYE: The debate at the time, it's not just should the United States enter the war or not but what does America stand for? I mean, what's the meaning of America?

[CLIPS]:

ANNOUNCER: Columbia presents another of its programs in which prominent speakers talk about current topics of vital national interest.

SARA FISHKO: The debate about America played out on the air. A Henry Wallace speech of 1942 had a clear “common man” message.

VICE-PRESIDENT HENRY WALLACE: Everywhere the common people are on the march. By the millions, they are learning to read and write, learning to think together, learning to use tools….

SARA FISHKO: Wallace was vice president under FDR. His widely-heard speech called for what he termed “the century of the common man.” He warned citizens that they must learn to self-govern and to fear the demagogues.

VP WALLACE: It is easy for demagogues to arise and prostitute the mind of the common man to their own base end. Such a demagogue may get financial help from some person of wealth who is unaware of what the end result will be.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

SARA FISHKO: The common man idea was picked up instantly by NBC. Not much more than a month later, the network ran a star-studded radio spectacular called “Towards the Century of the Common Man.”

PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE RECITATION: And to the Republic for which it stands.

SARA FISHKO: Next, it appeared in theaters as a US propaganda film, with patriotic music and images added to Wallace’s stirring words.

VP WALLACE: No Nazi counterrevolution will stop it. The common man will smoke the Hitler stooges out into the open in the United States. He will destroy their influence.

SARA FISHKO: The common man speech, Sam Tanenhaus reminds us, was a direct response to the views of Time Life magnate Henry Luce, whose famous essay in Life Magazine heralded what Luce had called “the American Century.”

SAM TANENHAUS: America would be the powerhouse that would lead the Western democratic alliance and kind of bring its industrial and democratic might to the world.

SARA FISHKO: A more imperialist idea of where America would wind up after the war. When the Luce essay appeared in Life, Orson Welles wrote, “If Mr. Luce's prediction of the American century will come true, God help us all.”

[MUSIC/COPLAND’S “FANFARE” UP & UNDER]

Aaron Copland, writing his “Fanfare” in 1942, commented with his music. The common man moment was dominating the discourse.

SAM TANENHAUS: Am I going to call this the Fanfare for Democracy? That was his first thought.

SARA FISHKO: Just as the composer was searching for a title for his piece.

SAM TANENHAUS: The second thought is, will I call it the Fanfare for the Four Freedoms ‘cause that’s the keywords of the day?

SARA FISHKO: By then, it seemed right to call it “Fanfare for the Common Man.” The title and the piece captured the public imagination. Copland had searched for an imposed simplicity in his music. This was one of the most celebrated examples.

JOHN CORIGLIANO: If you take “Fanfare for the Common Man,” he starts off that piece by having a melody. It jumps without scales. [PLAYING NOTES ON PIANO] Jump, jump, the next note.

SARA FISHKO: John Corigliano says in this case the simplicity comes from the distance between the notes.

JOHN CORIGLIANO: When he first harmonizes this, he harmonizes it only with notes five notes apart and four notes apart, so we get a very bare sound, instead of the full rich chord. [PLAYS CHORDS]

SARA FISHKO: But Copland also knew how to orchestrate to great effect.

[ORCHESTRA PLAYING]

So it sounded simple but it also sounded rich.

[ORCHESTRA PLAYING]

JOHN CORIGLIANO: I think Copland was searching for a language that was simple enough to be recognized but it wasn't simple-minded. It was the opposite of simple-minded, and I think a lot of his ideology comes into his music making.

SARA FISHKO: Later, the fanfare was added by Copland to his third symphony, and it took off to become the epitome of musical patriotism.

[ORCHSTRA PLAYING THIRD SYHMPHONY]

This was early in Copland’s spectacular run in the 1940s, one Americana style hit after another: the “ Lincoln Portrait,” “Danzón cubano,” “Music for the Movies,” “Rodeo.”

JUDITH TICK: Culminating in a masterpiece, which is “Appalachian Spring.” And there, he uses Shaker tunes, which, of course, are the essence of simplicity.

SARA FISHKO: “Appalachian Spring” won the Pulitzer Prize for Copland in 1945 and by the end of the ‘40s he was back in Hollywood to do more music for film, including William Wyler’s The Heiress.

[CLIP]:

MALE PRESENTER: The envelope, please.

SARA FISHKO: And that earned him Hollywood's highest honor.

MALE PRESENTER: The winner is Aaron Copland for The Heiress.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUSE]

OSCAR HOST: And now, Ladies and Gentlemen…

SARA FISHKO: He fired off a note to his friend and fellow composer Leonard Bernstein: “Did you hear, I won an Oscar for The Heiress? Price goes up.”

He’d climbed to a great height –

[MUSIC/UP & UNDER]

- but the world was changing.

[CLIPS]:

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Calling the House Un-American Activities Committee to order, Chairman J. Parnell Thomas of New Jersey opens an inquiry into possible Communist penetration of the Hollywood film industry.

SARA FISHKO: The House Committee on Un-American Activities had already begun its work in 1947, the same year as the start of the Cold War.

MAN: Are you a member of the Communist Party or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?

SARA FISHKO: And they went right for Hollywood and the headlines.

MAN: That’s not the question. That’s not the question!

HEARING SOUNDTRACK UP & UNDER]

SARA FISHKO: American politics was taking a radical right turn. Senator Joseph McCarthy had been voted in during the 1946 elections and soon he broadened the targeted attacks.

SEN. JOSEPH McCARTHY: One Communist on the faculty of one university is one Communist too many.

[AUDIENCE CHEERS]

THOMAS DOHERTY: When we talk about McCarthyism we always associate it with a particular kind of boorishness of the man.

SEN. JOSEPH McCARTHY: One Communist among the American advisors at Yalta was one Communist too many.

THOMAS DOHERTY: And, frankly, there is kind of a class prejudice in this, and McCarthy’s accusations against these Ivy Leaguers is one of the cultural undertones of this entire era, where you have people like McCarthy, kind of a working-class Irish German, and Roy Cohn, a sort of pushy New York Jewish guy, up against the aristocrats of the State Department.

THOMAS DOHERTY: He’s the common man, you know, with the doubled-up fists who’s going to chase the kind of effete sissy, sellout Harvard types away from government. And don't think that's gone away or ever will because it won’t. And out here it’s a division right inside the American character.

SEN. JOSEPH McCARTHY: We’ve got to dig and root out the Communists and the crooks and those who are bad for America.

SARA FISHKO: And as FDR used radio, so McCarthy used media in a different era.

SEN. JOSEPH McCARTHY: And if we have a Republican president, we’ll be able to get those records, I’m sure.

THOMAS DOHERTY: McCarthy realizes that you could get power simply by being a media superstar in the age of radio and then especially TV, which starts coming into many American homes by 1953, 1954. So McCarthy can use his live television news conferences, his telecasts of the Senate investigations to promulgate his vision of America and, not incidentally, to gain a kind of political power that would have taken decades to get if he had done it the old-fashioned way of slogging in the US Senate.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

SARA FISHKO: Our hero, Mr. Copland, was caught in all this. He found himself in the publication Red Channels, along with 150 other cultural figures and journalists who were now officially on a list of the unemployable due to their political beliefs and affiliations, a blacklist. And there were a lot of lists then, which created an atmosphere of finger pointing, innuendo and fear. The attorney general had a list of groups considered subversive, that is, all of the leagues and collectives and alliances artists and activists had joined during the common man era. If you’d ever belonged to one, you were a suspicious character. Not only artists but also teachers, civil service workers, everyone was suspect. People in unions and other organizations were being asked to sign loyalty oaths.

Later, Copland was questioned by Senator McCarthy and Counsel Roy Cohn in a special executive session of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Government Operations. During the two-hour grilling, Copland was courteously evasive, not refusing to answer, but rather cannily dodging every verbal bullet that came his way.

What changed for America's most distinctively American composer? Well, for a while, Hollywood was not an option. He was on the blacklist. And Senator McCarthy, of all people, knew the power of cultural communicators, so he influenced the State Department to create obstacles for their work. Copland scores and recordings were banned in hundreds of US overseas libraries, access officially denied.

[DRAMATIC ATONAL MUSIC]

But what changed most dramatically was his music. The creator of this widely loved and accepted American sound adopted a more atonal internationalist approach, much more popular after the war. Some of his supporters were mystified by the change. His best-known piece of the 1960s was “Connotations for Orchestra,” a much darker work for a darker, more individualistic era.

He said, in 1968 –

AARON COPLAND: The idea of writing specifically American-sounding music is definitely out.

SARA FISHKO: Because the ideas and collective spirit Copland helped to create were out. He’d been an idealist, an optimist, a patriot, and his music had captured that. Perhaps he remained all those things but he more or less abandoned his signature sound and he was no longer quite the shining star of music he once was. It’s just very difficult to be a, a creative person who lives for many decades and, you know, establishes an identity.

JUDITH TICK: It’s hard to ride the waves of indifference when you’ve been used to so much prominence. And I think for Copland it was very painful.

SARA FISHKO: He still hoped to reach people with his work. He said on The Today Show in 1970;

THE TODAY SHOW HOST: How does a man – I heard you ask it once time – how does a man go on writing when nobody listens to what he writes?

AARON COPLAND: I’ve never understood that. It’s a – it seems to me an impossible situation to find yourself in.

HOST: Yes.

AARON COPLAND: But I don’t know, the urge to write is the main thing that moves you.

SARA FISHKO: A story of the search by a composer, and a country, for a national identity, with profoundly divided results.

[MUSIC/MUSIC OUT]

BOB GARFIELD: Sara Fishko reported this piece for the WNYC podcast series “The United States of Anxiety.”

BOB GARFIELD: That’s it for this week’s show. On the Media is produced by Meara Sharma, Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jesse Brenneman, Micah Loewinger and Leah Feder. We had more help from Jane Vaughan. And our show was edited - by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Terence Bernardo.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And Bill Moss mixed the Aaron Copland piece. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s vice president for news. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios.

This week, we bid the fondest of farewells to an extraordinary producer and a great soul, Meara Sharma, who’s leaving us for a future across the sea. She played a decisive role in some of our best work, including the Poverty series. We’ll miss her – a lot!

I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: Yes, Meara, we will miss you. All best of luck in London, and be sure to look right before crossing. I’m Bob Garfield.