The Shameful History of US Intervention in Latin America

( ASSOCIATED PRESS / AP Images )

BOB GARFIELD: Amid all the confusion surrounding the power struggle in Venezuela, National Security Adviser John Bolton raised a yellow warning flag about American military intervention–or anyway, a yellow legal pad which he carried into a white house press briefing conspicuously displaying a single provocative notation.

[CLIP]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Bolton was holding a notepad with the words five thousand troops to Colombia– clearly visible. The White House would only say that all options are on the table. When it comes to American intervention in Latin America, history tells us all options are always on the table. Whether through direct military action or CIA mischief, the United States has variously propped up brought down, or attempted to bring down, regimes in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Argentina, Haiti, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Grenada and Uruguay. Just about every tree in this hemisphere. According to Stephen Kinzer, author of Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change From Hawaii to Iraq, US backed coups and invasions tend to follow three steps.

STEPHEN KINZER: The first thing that happens is that that country makes some kind of a problem for an American corporate interest. It tries to impose taxes or it limits the amount of land they can own or tries to subject them to local labor laws. And that company then complains to the US government. That's phase one. Then inside the American political process, the motive changes, it morphs. Then we decide if country X is bothering an American company it must mean that that country is an enemy of ours. So we're intervening for strategic reasons. That's phase two. And then phase three comes when it's time for us to explain why we did it, to justify it. Then we forget both of those motivations. We say, 'oh it was another reason and that was we did it to protect the poor suffering masses in that country who are being brutalized.' This is something that always works with Americans. We are a very compassionate people. Our leaders know this about us.

BOB GARFIELD: The mother of all such interventions you believe was Guatemala.

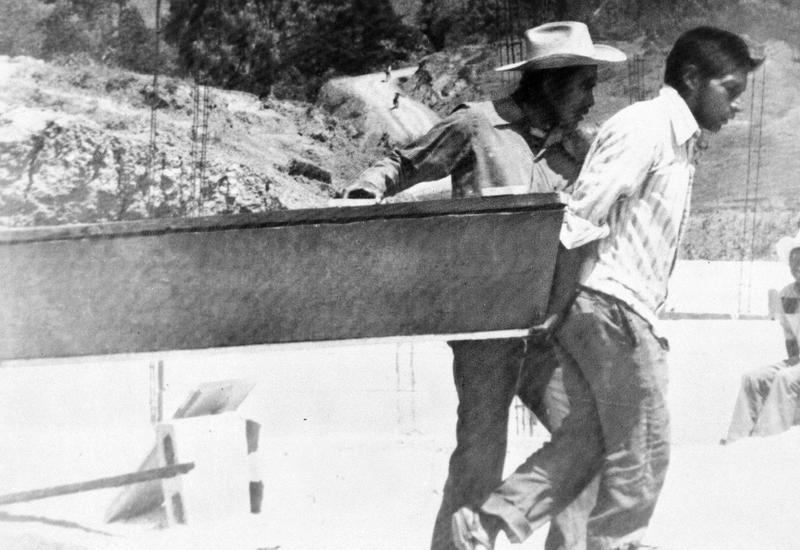

STEPHEN KINZER: So what happened in Guatemala in 1954 was a classic archetype of the way we operate and what angers us. The Guatemalan government finally, in the late 40s and early 1950s, became democratic. The great injustice at that time, in Guatemala, was that although large numbers of people were living on the edges of starvation. United Fruit Company owned hundreds of thousands of acres that it didn't use. So under the Arbenz government in Guatemala in the early 1950s, congress passed a land reform law that required large landowners, principally United Fruit, to sell their unused land to the government which would then cut it up and divide it up for peasant families. The outrage that a United Fruit felt coursed through the White House and led us to conclude that Guatemala must be a hostile enemy. And that led us into the intervention which overthrew the only democracy Guatemala's ever known in 1954. Look back at the results. A civil war began a few years later and that civil war lasted for 30 years.

BOB GARFIELD: It's sickening on the face of it. More sickening still in the fact that the US press, the watchdogs of our government, were leading the cheers.

STEPHEN KINZER: The United Fruit Company hired a very skilled propagandist, Edward Bernays, the father of public relations, to persuade Americans that Guatemala was their enemy. They started producing films like one called 'Why the Kremlin hates Bananas.'.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: There is a very special reason why they must hate bananas in Moscow. United Fruit has put to use for production, hundreds of thousands of acres of otherwise unproductive tropical lands. [END CLIP]

STEPHEN KINZER: Americans would slowly come to believe this fiction that some evil communist repressive regime had seized Guatemala and had proven its evil nature by bothering the United Fruit Company. They would bring journalists in groups down to Guatemala and these journalists would just show up at wherever United Fruit wanted to take them write down what the executive said and then go back home and report this as reality. The few people who tried to write that actually land reform was an urgent necessity and people were starving in Guatemala were marginalized and their reports were never allowed to reach the American peoples. It was one of the most shameful episodes in the history of the press. Until we get up to the modern day.

BOB GARFIELD: And with ongoing consequences in the hemisphere, it was used as an example by the likes of Fidel Castro and other revolutionaries in the ensuing decades as to American imperialism. So during the period when Arbenz was in power in Guatemala in the early 1950s, lots of progressive activists from all over Latin America were fascinated with what was happening in Guatemala. They wanted to go and see how does land reform work? How does labor organizing work? One of those young idealists who came to Guatemala was Che Guevara. He was there and he witnessed the coup. After the coup, he met Fidel Castro. Che told him in the end, 'here's the central lesson we should learn from Guatemala. It is not possible, in Latin America, to impose a serious social reform program under the auspices of a democracy. Democracies are open societies. The CIA will use that openness come in and crush you. So if we ever take power in Cuba, we have to crush all opposition. We cannot allow a free press. We cannot allow free speech.' That became not only the template for Cuba, but the ideal because they saw the example of what the United States had done in Guatemala.

BOB GARFIELD: Let's move ahead to some more recent history 2009 and Honduras.

STEPHEN KINZER: So in 2009 we had a president in Honduras who we didn't like and the reason was he was friendly with Hugo Chavez the Venezuelan leader–who we took as kind of the new Castro and the great enemy that we faced in Latin America. So we had him in our sights and in the middle of the night, military officers crashed into his house dragged them out in his pajamas and put them on a plane and sent him out of the country. We cheered. And what has happened since then? The government has become repressive. It has been re-elected, despite a constitutional prohibition on reelection. It has become one of the highest murder rate countries in the world and the so-called caravans that are coming through Mexico towards our border are made up largely of Hondurans. This is not unrelated to our intervention there.

BOB GARFIELD: And this intervention is not at the hands of the Eisenhower administration, not of the Ronald Reagan administration. It was the Obama administration, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

[CLIP]

HILLARY CLINTON: As President Obama said today, we have taken this position because we respect the universal principle that people should choose their own leaders whether they are leaders we agree with or not. [END CLIP]

STEPHEN KINZER: Hillary Clinton applauded the coup in. Her memoir she wrote a great paragraph about what a wonderful thing it was and how we just allowed the Hondurans to choose their own fate. As it started to go really bad, I did notice that in the paperback edition of Hillary Clinton's memoir she's taken out that paragraph.

BOB GARFIELD: How does the Venezuela situation fit into your three stage template?

STEPHEN KINZER: First of all, I'm quite surprised in some ways, impressed, to see that our national security adviser Mr. Bolton announced the other day that we are interested in taking control of the oil in Venezuela.

[CLIP].

JOHN BOLTON: We're in conversation with major American companies now that are either in Venezuela or in the case of Citgo, here in the United States. It will make a big difference to the United States, economically, if we could have American oil companies really--[END CLIP]

STEPHEN KINZER: Now you're not supposed to say that. The Americans are supposed to keep that a secret and say, 'we're only doing it to help the starving Venezuelans.' But if it's going to be a military intervention this has to be debated in Congress. We don't do this anymore but our constitution requires it.

BOB GARFIELD: Oh and just for a little icing on top, the Trump administration has brought in Ronald Reagan's old conquistador, Elliott Abrams. Because I suppose Hernan Cortez was unavailable.

STEPHEN KINZER: Haha.

BOB GARFIELD: What are we supposed to make of this development?

STEPHEN KINZER: The appointment of Elliott Abrams is surely mind boggling, especially for us old fogeys that remember the 1980s. So back then I was a New York Times correspondent in Central America. Elliott Abrams was a principal perpetrator of US policy in Central America. He was a main supporter of the Contra Project in Nicaragua. That also entailed the intense militarization of Honduras. So we're not just taking the mentality of the interventionist 1980s in Central America and bringing it back to life. We're actually bringing back the actual person that did it. How do you think this looks to people in Venezuela and the rest of Latin America?

BOB GARFIELD: You and I have previously discussed on this very show the media's fascination with war and the kind of bellicose jingoism that we as an institution have embraced over the decades–to drag the country into conflict beginning with Cuba a century ago. What is that history and what must we take care of as the press not to get caught doing here?

STEPHEN KINZER: Back in 1898 when William Randolph Hearst was inventing the concept of yellow journalism, he understood a principle that the press still understands today. And that is if you want to get people to tune in every day or by every day what you really need is a running story–a story that goes on and on. The best running story of all is a war. The American involvement in the Spanish American War was largely whipped up with stories about the evil brutalities being perpetrated in Cuba, many of which were written by reporters in New York but never even been to Cuba. If you move that up to the present day, I think you see something of the same thing but there's a more sophisticated patina to it. In some ways, it's even more pernicious. In the American press, there's a sense among many many editors and reporters that the press's role is to explain to people why it's important that we follow the policies our president has enunciated. That's not what the press is for. We are not supposed to be just not stenographers writing down what leaders say and then sending it off to the American people. We're supposed to be asking questions. 'Wait a minute, is this really a big danger as we say? Is everything they say really true? Is it really so sure we're going to succeed? But our press doesn't do that because that's not what the government in Washington wants them to do. And once you rebel against that paradigm, you become considered what John McCain called a 'wacko bird'–someone who is completely off the consensus. And the power of the Washington consensus to pull people into it is truly awesome and impressive.

BOB GARFIELD: So we're speaking Wednesday. This just in, it turns out that the New York Times published an op-ed by Guido, calling on the democracies of the world to support his claim to the presidency–because that's the only way they're going to get out of the hell that Venezuelans in now.

STEPHEN KINZER: Well congratulations to the New York Times. I hate the fact that most of the Democratic Party and most of the Republican Party is in this war consensus. I hate the fact that most of the think tanks in Washington are in this consensus. But as a person who has spent his life in the press, what I hate the most is that the press has been drawn into this. If you look at the commentary pages of all major American newspapers it's so monochromatic. It goes between neo-cons and liberal interventionists. There is no fundamental questioning of the premises on which these interventions are launched. And that puts us back in a position where the press really almost as shameful as it was in its performance way back in the Spanish American War in 1898.

BOB GARFIELD: Stephen, thank you very much.

STEPHEN KINZER: Always good to be with you.

BOB GARFIELD: Stephen Kinzer is a professor of international relations at Brown University.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Coming up, in China making cultural suppression look like summer camp. This is On The Media.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER].