The Secret Life of Novelizations

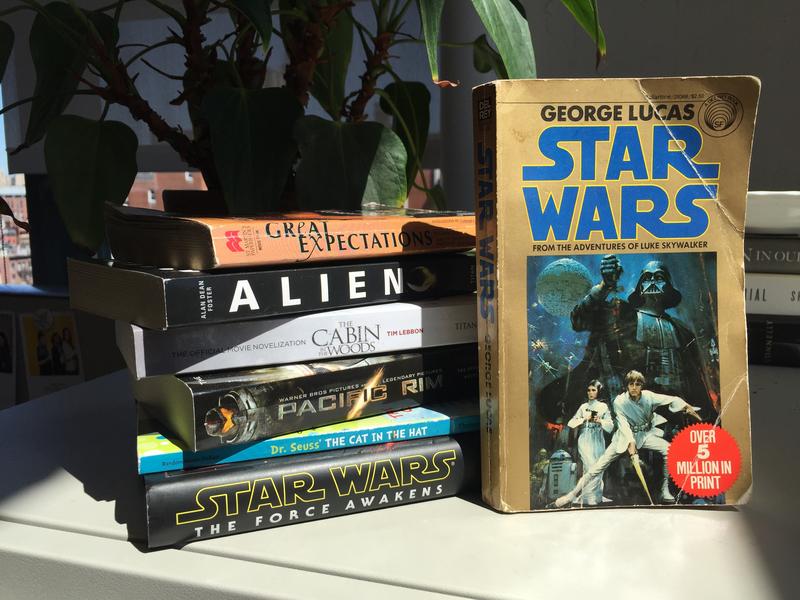

( Jesse Brenneman / WNYC )

It seems that we all might do well not to speculate too much about future plans when it comes to the publishing industry. Take the strange case of movie novelizations, which were supposed to die with the advent of VHS because, after all, why read the novel if you can watch the movie over and over? And now we are in an era of ubiquitous streaming video, so, so should novelizations still be a thing? Well, they’re still a thing but no more respected than ever. OTM Producer Jesse Brenneman reports.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: You know the experience. You’re standing in an airport or the grocery store checkout lane and you notice a glossy paperback titled, say, Batman versus Superman and you think, I didn’t know that was a book first. And then you see the dreaded words, “Adapted from the screenplay” and you think - oh, and you keep moving. No, there's not much respect for the film novelization, and nobody knows it better than the people who write them.

MAX ALLAN COLLINS: But it seems to be the only thing that people recognize, so I usually say “novelization” and then in parentheses say (dreaded term).

JESSE BRENNEMAN: Max Allan Collins is author of over 30 novelizations, including, Saving Private Ryan, The Mummy Trilogy and Waterworld. Like many authors, he's worked his entire professional life to get out from under our disdain.

MAX ALLAN COLLINS: The nasty, and sometimes-deserved, reputation of being sub-literature.

LEE GOLDBERG: That you have a bunch of writers who are not good enough to write books of their own, just take a script and type it in book form for a quick check over a weekend.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: That’s Lee Goldberg, author of what he prefers to call “media tie-ins,” including two successful series of novels based on the television shows, Monk and Diagnosis Murder. Goldberg and Collins were both fed up with the contempt for a trade that employs hundreds of writers and creates stacks of bestsellers, so they cofounded the International Association of Media Tie-In Writers, or IAMTW.

LEE GOLDBERG: Or I Am a Tie-In Writer. You know, the Mystery Writers of America, the Science Fiction Writers of America, the Romance Writers of America look down their noses at these books, and we thought it was time that the authors toiling in this world got some respect, also demystified what they were doing, educated other writers and the media and readers about what goes into writing a tie-in novel.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: So what exactly does go into writing a tie-in novel? First of all, a lot more than just copying and pasting.

MAX ALLAN COLLINS: I would largely throw the dialogue and the script away, because I feel that movie script dialogue and novel dialogue are completely two different things.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: Max Allan Collins.

MAX ALLAN COLLINS: Movies have a real habit of cutting from A to C or A to D and people are hip enough to just sort of fill that in. But in a novel, the writer is expected to tell you how they got from, you know, the forest to the city. So it’s a whole different way of viewing the material.

ELIZABETH HAND: The very first novelization I did was 12 Monkeys.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: That's Elizabeth Hand, who later novelized the 1998 X-Files film and Halle Berry's Catwoman. Hand was an author in her own right but when tackling that first adaptation, she turned to her friend and fellow novelizer, Terry Bisson.

ELIZABETH HAND: And then I said, Terry, what do I do, how do I do this? You know, I’m looking at this screenplay and there’s just – there’s n- there’s not a lot there, there’s just a little dialogue. And he said, well – and he has this great Kentucky drawl – he said, well, the first thing you gotta know is that when somebody walks into a room and sits in a chair, if that’s what the stage direction says, he doesn’t just walk into the room and sit in the chair. He ambles slowly across the Oriental rugs that are covering the polished hardwood floors, and with a sigh, he sank deeply into the beautifully-upholstered velvet wing chair. [LAUGHS] And I said, okay, well, I guess I can do that.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: My eyes were opened to the riches of the genre when I stumbled upon the novelization of the original Star Wars film.

[STAR WARS THEME MUSIC/UP & UNDER]

I was an adolescent Star Wars obsessive, and the book was amazing, not because it was just like the film but because it was so different. In addition to new scenes and, and history, there were changes so arbitrary that they just had to have some deeper meaning. For instance, instead of the famous “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away,” the book begins with, “Another galaxy, another time.”

ALAN DEAN FOSTER: Well, it was just a film. I mean, everything hadn’t been codified and brought down from Mount Sinai.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: That’s Alan Dean Foster, author of the original Star Wars novelization, which he ghost-wrote for George Lucas. And those cryptic changes that I endowed with such significance? Chances are he made most of them up, which he could do because in 1976 George Lucas was just the director of American Graffiti, and Star Wars was not yet a multi-billion-dollar industry.

ALAN DEAN FOSTER: Basically, it was, here’s the screenplay, here’s a couple of quick shots of people involved in the film. I saw about ten minutes of rushes one day at Industrial Light & Magic, go write the book. And I, I finished the book, I turned it in. George read it, said, that’s fine. And that was it.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: That a Star Wars fanatic like me could read Foster's book and think it was the original source material is, for novelizers like Max Allan Collins, the dream.

MAX ALLAN COLLINS: I run into people all the time that think what a genius I must have been. You know, I created CSI and I created Saving Private Ryan and I created Air Force One and all this stuff, which is just absurd. But I take some credit because the book was enough of a legitimate experience to them that they didn't just feel they were getting the literary equivalent of a lunchbox.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: Which raises the question: Why is our admiration so contingent upon the order of the adaptation? For authors like Alan Dean Foster, it's a source of constant frustration.

ALAN DEAN FOSTER: It doesn’t make any sense that you can take a bestselling book that sold millions of copies all over the world, like say, Ben-Hur, extract the screenplay from it, win an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay and everybody says that’s a great piece of writing, when that's much easier to do than take a screenplay and make a novel out of it.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: And plenty of novelizers have been stuck with unenviable tasks. There’s a novelization of the Britney Spears film, Crossroads.

[CLIP]:

BRITNEY SPEARS CHARACTER: Now I know that life doesn't always go my way. It feels like I'm caught in the middle, and that's when I realize that I'm not a girl; I’m not yet a woman.

[END CLIP]

JESSE BRENNEMAN: And then there are those novelizations whose very existence is mind bending, like this one.

[CLIP]:

ANNOUNCER: Ethan Hawke, Gwyneth Paltrow, with Anne Bancroft and Robert De Niro, Great Expectations.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: The cover of which reads, “Novelization by Deborah Chiel, based on the novel by Charles Dickens, based on the motion picture written by Mitch Glazer.” But the cream of the weird crop is easily the children's novelization of The Cat in the Hat, starring Mike Myers. The original Cat in the Hat begins like this.

READER: “The sun did not shine. It was too wet to play. So we sat in the house all that cold, cold wet day.”

JESSE BRENNEMAN: The novelization begins like this.

READER: “The worst day ever. It really was. For starters, I was sitting in the family room staring out the window. I mean, that's not the way I usually spend my Saturdays, but my Game Boy was taking a ride in my mom's purse and the TV was tuned to C-Span. On a good day…”

JESSE BRENNEMAN: And yet sometimes, less-than-stellar subject matter leads to the most successful novelizations. Lee Goldberg.

LEE GOLDBERG: Elizabeth Hand wrote the novelization of the Catwoman screenplay. The Catwoman movie was a bomb, with Halle Berry. The book was such a big bestseller, they talked about doing sequels to her novelization.

ELIZABETH HAND: There was really nothing in the screenplay, at all, to go on with this character, so what I ended up doing, there was a character in the screenplay, a, a professor of catology [LAUGHS] who tells her how she got her magic cat powers.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: Elizabeth Hand.

ELIZABETH HAND: So I ended up writing three or four little stories within the story that were drawn on different legends about cats, and I sort of held my breath to see if they would buy it.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: And often, the studios don't. As Max Allan Collins learned the hard way, when he found himself in the unique position of writing the novelization for the 2002 film, Road to Perdition, based on his own graphic novel.

MAX ALLAN COLLINS: I sat down and I wrote a 70, 80,000-word novel, very faithful to the movie script, but filling in things from the graphic novel. And they came back to me and said, we want nothing in here that isn’t in the script, nothing. And it was my characters. They were not allowing me to do anything with my characters. That was a very unhappy experience.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: So, why do they do it?

LEE GOLDBERG: Sebastian Faulks and William Boyd are literary novelists, and yet, they pandered to do a James Bond novel? Why?

JESSE BRENNEMAN: Lee Goldberg.

LEE GOLDBERG: Well, it’s James Bond. A lot of authors feel the same way about Star Wars or Star Trek or the X-Men or Monk [LAUGHS] or whatever. They, they want to have a chance to write those characters that they love, to explore those worlds.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: For Max Allan Collins, it helps to remember who his intended audience is.

MAX ALLAN COLLINS: I did Waterworld. I don't know if I want to know the 55-year-old guy that picked up Waterworld and read it. I'm not really sure I want to hang with that guy. But the 14-year-old who read it and wrote me a letter about it, you know what, he's gonna grow up, he’s gonna be reading all through those years, and if he loved my book, I got a customer.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: Plus, you know.

ELIZABETH HAND: Writers always need money.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: Elizabeth Hand.

ELIZABETH HAND: Samuel Johnson said, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.”

ALAN DEAN FOSTER: Beethoven didn’t sit around turning out symphonies for fun.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: Alan Dean Foster.

ALAN DEAN FOSTER: They were all done on commission. They were all done to be paid. And Rembrandt sat around painting fat businessmen all day, and I don't think that that's probably what he wanted to paint all the time.

JESSE BRENNEMAN: And as you dive further into the history of novelizations, something else starts to become clear. The relationship between films and books is not always so straightforward. The first hit novelization was 1932's King Kong, which was released as a promotion before the film.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

Fritz Lang's classic Metropolis was based on the novel written by his wife, Thea von Harbou, which she wrote with the movie in mind. And Arthur C. Clarke's 2001 Space Odyssey novel came out after Stanley Kubrick’s film, but Kubrick and Clarke developed the book together, as a precursor to the movie. In that screenplay, there's a line that seems to speak directly to the novelizer’s task.

[2001 CLIP]:

HAL: I am putting myself to the fullest possible use, which is all I think that any conscious entity can ever hope to do.

[END CLIP]

JESSE BRENNEMAN: Or perhaps, on more cynical days, it’s a line from another classic.

[STAR WARS EPISODE IV - A NEW HOPE CLIP]:

HAN SOLO: Look, I ain’t in this for your revolution, and I’m not in it for you, Princess. I expect to be well paid. I’m in it for the money.

[END CLIP]

JESSE BRENNEMAN: A line which is in the novelization, albeit with a few minor changes. For On the Media, I’m Jesse Brenneman.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Coming up, one man who stole books one by one and another who literally sells them by the foot.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]