BROOKE GLADSTONE: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

In his first words as president of the United States, as if still on the campaign trail, Donald Trump described a country in ruins.

[CLIPS]:

PRESIDENT TRUMP: Mothers and children trapped in poverty in our inner cities, rusted out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation.

BOB GARFIELD: Even Trump’s optimistic plans for redeveloping our hellscape were rife with darkness and foreboding.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: We assembled here today are issuing a new degree to be heard in every city, in every foreign capital and in every hall of power. From this day forward, a new vision will govern our land. From this day forward, it's going to be only “America first, America first.”

[CROWD CHEERS][END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: A decree, he said. Democracy has no decrees. “America first,” he said, echoing the isolationist and fascism-friendly movement of the early ‘40s. Ladies and gentlemen, “Elvis has left the building” on Friday opened a new act. It’s billed as patriotic, whether also lawful and democratic remains unanswered.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Even as President Trump intoned those words from the podium, the whitehouse.gov website was being populated by a half dozen top priorities, first, to eliminate the government’s climate action plan and revive the coal industry, second, to defeat ISIS and rebuild our military, third, to create jobs by cutting taxes and regulations, fourth, to rebuild the military - I know, that was also number two – fifth, to reduce crime by supporting gun rights and building a border wall and sixth, to pull out or renegotiate our trade deals. No surprises there, no specifics either.

What is a little surprising is that a show called On the Media hasn't yet focused on what President Trump’s loathing of the media means for journalism. Time’s a-wastin’, so we’ll start by recalling his slap down of CNN at last week's press conference.

[CLIPS]:

JIM ACOSTA: Since you are attacking our news organization –

PRESIDENT TRUMP: No, not you, not you.

ACOSTA: - can you give us a chance?

TRUMP: Your organization is terrible.

ACOSTA: You’re, you’re attacking our news organization.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The media were none too happy with the experience, and apparently neither was the President-elect.

[CLIPS]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Trump threatened a blow to the White House press corps, maybe moving the briefings and maybe journalists’ workspace across the street.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: “They are the opposition party. I want ‘em out of the building. We are taking back the press room.” That’s a quote from a report in Esquire Magazine.

FEMALE CORRESPONDANT: Is he going to move them to the EOB from the press room?

MALE CORRESPONDANT: He sure is, absolutely.

MALE CORRESPONDANT: Is he really? Wow.

FEMALE CORRESPONDANT: That’s – that’s big.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Shocking, until a few days later at least, when Trump declared that out of the goodness of his heart he would allow the press to remain where they are, for now. But if he were to move the press corps, would it be as shocking as it's been portrayed? Time Magazine’s Olivia Waxman says, neh. With the help of the Times Archive, Waxman traced the path of the White House press and found that it never did run smooth. Olivia, welcome to OTM.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Thanks for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Take us back to the very beginning. What was the press/government relationship at the founding of the country?

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Journalists were not allowed to attend the Constitutional Convention, nor were they allowed in early state legislatures or the Continental Congress. Actually, a gossip columnist named Anne Royall literally had to steal John Quincy Adams’ clothes – [LAUGHS]

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- to get him to grant her an interview. She sat on his clothes on the bank of the Potomac until the bathing president granted her an interview.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] Was there anything that really jumped out at you as surprising when you went through the Archive of Time Magazine?

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Well, I was surprised that women had been the first to argue that everything in the White House should be public knowledge because taxpayers paid for its upkeep.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Emily Briggs of Philadelphia.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: She said, when we go to the Executive Mansion, we go to our own house. We recline on our own satin and ebony. BROOKE GLADSTONE: And then we get to President Grover Cleveland and you say that's when we begin to see the emergence of the White House reporter that we’d recognize today.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Right. So there’s a historian named Martha Kumar who pinpoints it to “Fatty” Price [LAUGHS] of the Washington Evening Star. He was one of the first reporters to work the White House beat. He sat at a table in a hallway and would pepper people with questions who were walking by. Martha Kumar found a letter that “Fatty” Price had written a White House staff member, saying, thank you for the tablecloth.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

So that seems to be the first sign we have that reporters were camped out, so to speak.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: We’re talking there of the 1880s, 1890s. You get to the 1900s, to Teddy Roosevelt, who really loved reporters.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Yes, he had a sort of newspaper cabinet that typically would meet with him during Roosevelt's early afternoon shave. And, if you can imagine, reporters got that kind of access in the early 20th century, enviable now, but Teddy Roosevelt did banish reporters to what he called the “Ananias Club” –

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- if the stories proved to be embarrassing for the president. And Fortune Magazine reported that the journalists would readily forgive him because he made, quote, “such astounding copy.” BROOKE GLADSTONE: Roosevelt had his favorites, whereas President Wilson seemed to open up his doors to a wide range of reporters, a lot of people, less intimacy.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Yes. Wilson’s private secretary, Joseph Tumulty, told reporters that the president would, quote, “look them in the face and chat with them for a few minutes.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: So on March 15th, 1913, 125 newspaper staffers showed up and Wilson said, “Your numbers force me to make a speech to you en masse instead of chatting with each of you, as I had hoped to do, and thus getting greater pleasure and personal acquaintance out of this meeting.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, FDR, like his relative Teddy Roosevelt, was catnip for the press, He gave, you write, nearly a thousand press conferences, almost twice a week?

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Time reported that he kept most White House news hawks fluttering happily. Those press conferences were ones where they had a real exchange of information. It was being compared to Prime Minister's Question Time in the UK. But he also locked the doors, so no reporters could walk out.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Of the press room?

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Yes. [LAUGHS]

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

On occasion, he would call correspondents liars or tell them to put on dunce caps.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Really? I guess it's okay to call a particular correspondent a liar if it's not being televised, but that's when the next big change happened, under Eisenhower.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: That’s a watershed moment. James Hagerty, Eisenhower's press secretary, had been on the campaign trail. He had worked with the press corps before. He knew what a difference the press made. So January, 1955 was the first televised news conference.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: With the president?

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Yes.

[CLIP]:

PRESIDENT EISENHOWER: Well, I see we’re trying a new experiment this morning. I hope it doesn't prove to be a disturbing influence.

REPORTER: Well, tomorrow is the second anniversary of your inauguration, and I wonder if you’d care to give us an appraisal of your first two years and tell us something of your hopes for the next two or maybe even the next six?

[LAUGHTER]

PRESIDENT EISENHOWER: Looks like a loaded question.

[END CLIP]

OLIVIA WAXMAN: They were thinking about it in the same way that Trump thinks about Twitter: This is our chance to get to the public directly, to be seen by the public directly.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But Hagerty edited the thing. It wasn't in the control of any TV network.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Right, and the New York Post was surprised at how scripted this was. I’ll quote from that article: “What is most notable in all the comment is the absence of protest over the censorship imposed by the White House, a censorship which the networks have supinely accepted. Thus, after Wednesday's conference, Hagerty deleted 11 of the 27 questions and answers before letting the show go on the road. For example, when asked about his delaying the reappointment of Ewan Clague as commissioner of labor statistics, the president confessed he had never heard of the fellow.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] Now, when you described LBJ's relationship to the press, in a way it kind of reminded me of Teddy Roosevelt, shaving, and you note that Johnson was pretty unceremonious, as well.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Oh, yes. A White House reporter said that he once answered reporters’ questions about the economy aboard Air Force One while stripping down until he was standing buck naked and waving his towel for emphasis.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Johnson just didn't have any boundaries, apparently. [LAUGHS]

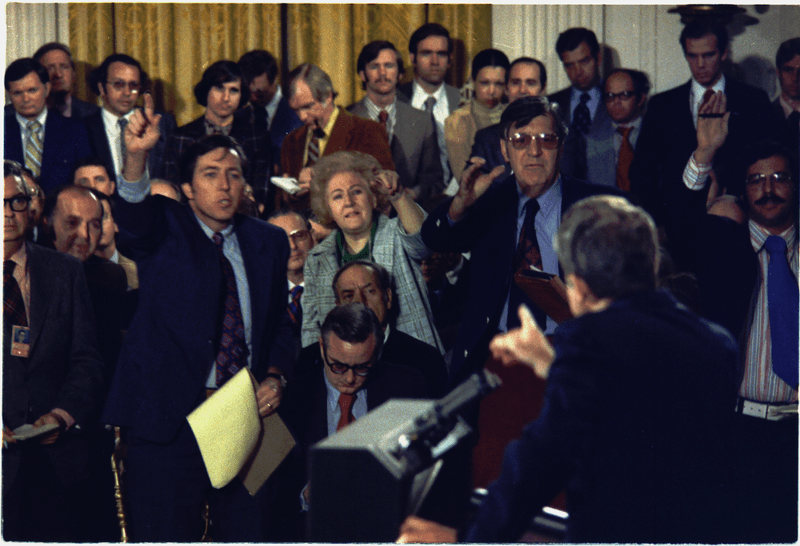

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So bringing us closer to what's probably the Trump mindset, it was President Nixon who gave the press corps their current home, but he wasn't thereby doing the press any big favor, right?

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Right. He wanted to keep presidential visitors and White House staff away from reporters, to designate a briefing room by putting a floor over the White House swimming pool. And when it opened in 1970, the Washington Post said it looked like the lobby of a fake Elizabethan steakhouse –

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- when the stage is hidden behind the curtain. And Ronald Reagan's Press Secretary James S. Brady, for whom the briefing room is named, used to joke that he and Reagan always planned on installing a trap door so reporters who got out of line would fall into the swimming if he pushed a button on his podium.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] In tracking the changes over centuries, do you notice a general trend?

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Presidents may tweak the format of things as they come into office but there were questions when Eisenhower came in, whether to keep reporters in the White House, and Nixon thought about not having a press secretary at one point. But ultimately, what happens is that presidents and their staff recognize that having a hundred reporters and TV cameras and photographers in one place, this is a great resource.

My favorite quote about precedence these days is from a special assistant to Calvin Coolidge, who said that if you can get the president to do a thing twice in a row, then every other president will do it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] I think the same could probably be said of the White House press corps. Olivia, thank you very much.

OLIVIA WAXMAN: Thank you for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Olivia Waxman writes for Time Magazine.