Part 2: Empire State of Mind

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On The Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. At the dawn of the last century, the arguments over imperialism didn't end with poets like Kipling and writers like Twain. There was a flash in time when it dominated politics and the press. In a world of shifting borders, how should, and how would, the adolescent United States big headed about its democratic values, grapple with the tensions inherent in capturing territory. Historian Daniel Immerwahr says that this vital debate blazed across America's consciousness like a comet–then vanished just as quickly out of sight and out of mind. Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan speaking out against imperialism in 1908.

[CLIP]

WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN: We do not want the Filipinos for citizens. They cannot, without danger to us, share in the government of our nation. And moreover, we cannot afford to add another race question to the race question we already have. Neither can we have all the Filipinos as subjects–even if we could benefit them by doing. For such an inconsistency would paralyze our influence as the world's teacher in the science of government.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: The racial logic here is totally transparent. And interestingly, a lot of the anti-imperialism was a racist anti-imperialism. The objection to Empire was that it would extend the borders of the United States in such a way that would include more non-white people in the country.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Even during our transcontinental land grab, Americans shied away from taking land that was populated by people who were not white.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah it's really extraordinary. So the United States expands a lot as the borders go west but was always operating a logic of the United States should seek to take lands, land that would then be used for white settlers. But it should not seek to incorporate large non-white populations. So after the United States fights a war with Mexico in the 1940s, militarily, it could seize a lot of Mexico. But politicians debate how much of Mexico does the United States really seek to annex? The southern border of the United States was carefully drawn in order to give the United States as much of Mexico as it could get with as few Mexicans.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: People of color cannot be trusted with the vote–that seems to be the governing principle here.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's the operative logic. Yes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And yet, didn't we in the Navassa decision that recognized that our off the mainland holdings were still subject to American law mean that the people who lived there had constitutional rights?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: You might think so. And the Supreme Court has to figure out what to do with this newly shaped United States. And there are a series of contentious Supreme Court cases starting in 1981 called the Insular Cases. And ultimately what the court decides is that constitutional rights apply in the mainland United States but they don't apply in Puerto Rico. And shockingly, this is still law today. You can have rights in Puerto Rico but they're not guaranteed by the Constitution because Puerto Rico exists in an extra constitutional zone. That's one reason, also, why if you're born in American Samoa, you're not a U.S. citizen. You're born in the United States but you're not born in the United States is covered by the Constitution, the 14th Amendment doesn't apply to you and therefore you're a U.S. national.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But you're not a citizen.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. And the history of the United States' colonial empire is the history of a lot of people who are U.S. nationals and either are not U.S. citizens, have to push to become U.S. citizens. And even when they receive that citizenship, for example Puerto Ricans have been citizens since 1917, the citizenship that they receive is statutory–i.e. it's provided by law not by the Constitution which also suggests that it can be taken away.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: One of the most clarifying things that you do in your book is to describe the tri-lemma that placed the central ideas of what the United States is in conflict with each other when confronted with its imperialist role.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. In the late 1890s, when many people in the United States are contemplating the future of the country, they realize that they can have an empire. They can have a country that's ruled by white people and they can have a country that has a representative government. But they can't get all three of them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why not?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Well, because think about it. Because now, the United States includes large non-white populations. So if the United States is going to continue to be Republican, Filipinos should have some kind of representative government and should have some kind of voice in the federal government of the United States. Those are the principles of Republicanism. They are taxed. They should be represented. That seemed like it was a founding and core principle of the country. But there are a lot of anti-imperialists, including William Jennings Bryan, who worry about what happens to the United States if suddenly non-white people have political power. Some people try to solve this one way by allowing the expansion of the United States but by rejecting its Republican principles. That's how Teddy Roosevelt thinks the United States should grow. It should have republicanism for the mainland but not for the entire country. Others, like William Jennings Bryan, seek to resolve this by not having empire, by limiting the growth of the country so that it doesn't have the problem of large, non-white populations who otherwise might need political representation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And there's a really loud debate about this.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: And it's in some ways a tragic debate because those are usually the two positions you hear. The United States should abandon Republicanism or the United States should limit itself to its contiguous borders. What you don't hear in the mainland debate is the third option: the United States should jettison white supremacy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: They never considered taking white supremacy off the table and yet they managed to reconcile these three incompatible ideas.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: And largely this happens by not talking a lot about the territory. So if you can brush it under the rug, the United States can still present itself, to itself and to others, as a republic–the distinctive and exceptional world power without being an empire.

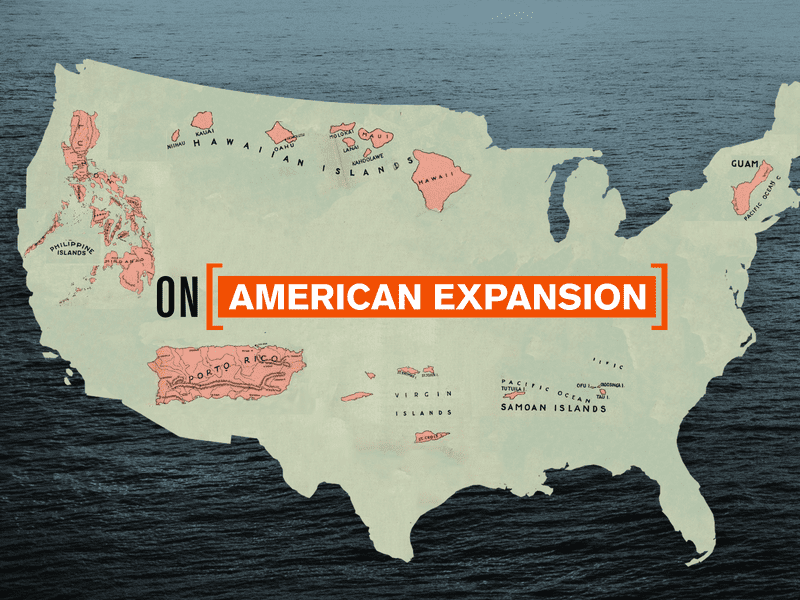

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The maps of Greater America start to go away?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Literally you can see the boxes erased. If you look at textbooks that are published by 1920, it is really hard to find a map that shows any part of the United States beyond the mainland.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And in terms of press coverage, let's talk about the invisibility of the people that the U.S. had come to rule. First, statistically.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: So the census is the statistical self-portrait of the nation. And if you look at the census from 1910, from 1920, from 1930, the first page in the population report will say, 'this is the population of the United States. And here is the population of its possession.' But everything after that in the census–how rural or urban is the population, how long do people live, what kind of jobs do they have–all these ways in which the United States seeks to understand, itself those calculations are implicitly just about the mainland. And the argument is that people who live in the territories are just too different to be included in the calculation. So essentially, they are relegated to the shadows.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So they're invisible in our numbers, more or less? And they're also invisible in American popular culture. I was struck by your discussion of the films about the long march in Bataan.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. So one of the more dramatic events in World War II is the Japanese conquest of the Philippines. And this becomes the single bloodiest thing ever to happen on U.S. soil. World War II in the Philippines ultimately kills 1.5 million people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Wow.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: About 1 million of whom are Filipinos or U.S. nationals. That's two civil wars. And there is very little registering of that on the mainland during the war, and frankly, there's very little registering of that now. It's not the kind of thing you find in textbooks. During the war, the thing that you see most about on the mainland is these wars about a fight in the Bataan peninsula.

[MU SIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Where Filipino soldiers and soldiers from the mainland were making a last ditch defense of the Philippines against Japan right before the archipelago got occupied and conquered. But what's so interesting about these films is they focus with laser like intensity on the White soldiers.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Our club on Bataan took another rap on the chin last night. [CLIP UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: So the tragedy of the loss of the United States' largest colony, a tragedy that will lead to the single bloodiest thing that ever happens in U.S. history, this is entirely understood as something that happens to characters who are played by like people like John Wayne.

[CLIP UP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: By then the Air Force will have won the war, I suppose. Only where is the Air Force? [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: The Filipino presence is almost completely erased from their perception of World War II, even when it's taking place in the Philippines.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Obviously, if people are viewed as lesser and if they are invisible, they're more vulnerable. Tell me the story of Cornelius Rhoads who was sent by the Rockefeller Institute to Puerto Rico to study anemia.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah. Cornelius Rhoads, Harvard trained doctor arrives in Puerto Rico in the 30s. And he regards Puerto Rico as a sort of island sized laboratory. So here's what we know. First of all, he intentionally refuses to treat some of his patients just to see what will happen. He also seeks to induce diseases in others by restricting their diets. He described some of them to his colleagues as experimental animals. He sits down and he writes to a colleague in Boston, one of them most extraordinary letters that I've read in U.S. history and he says, 'I am here in Puerto Rico. It's beautiful except for the Puerto Ricans.'.

[CLIP]

ACTOR: They are beyond doubt the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate and thievish race of men ever inhabiting this sphere. It makes you sick to inhabit the same island with them. They're even lower than Italians. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: This island would be great if something could be done to exterminate the population.

[CLIP]

ACTOR: I have done my best to further the process of extermination by killing off eight and transplanting cancer into several more. The latter has not resulted in any fatalities so far. The matter of consideration for the patient's welfare plays no role here. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: He leaves the letter out. It's discovered by the Puerto Rican staff. It seems to confirm all of the fears that Puerto Ricans have about mainlanders and it becomes a scandal on the island.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And this letter helps to fuel the nationalist movement of Pedro Albizu Campos.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. There's already a small nationalist movement in the 1920s. Pedro Albizu Campos is at the head of it. But in the 1930s, economic depression and then the issue of this letter, turned it into a major force in Puerto Rican politics. And Albizu passes this letter around to anyone who will listen. He sends it to the Vatican. The appointed colonial governor who's a mainlander describes it as a confession of murder. So there is an investigation and how that investigation plays out is really telling. First of all, Rhoads just leaves and there's an investigation without him. And Rhoads' defenders say a few contradictory things. He was drunk. He was joking. He was angry. But the point is that he didn't actually kill eight people. So the government, which is staffed by appointed mainlanders, runs an investigation. Finds another letter that is as the governor sees it worse than the first, which is hard to imagine. But we don't know what that letter says because the government suppresses it, destroys it and decides that Cornelius Rhoads was crazy and intemperate but that he didn't actually kill people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So maybe he was intemperate maybe he was a little out of his mind. He paid the consequences by being appointed the vice president of the New York Academy of Medicine and in the Army during World War II, Chief Medical Officer in the Chemical Warfare Service.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah and he goes on to have this illustrious career in medicine and basically suffers no consequences. But then, in the army in the Chemical Warfare Service, he gets another go.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Meaning he gets to use people as experimental animals again.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Exactly right. The United States government is seeking to develop chemical weapons in case World War II becomes a gas war, which it never really does. And overall some 60,000 people are tested on. And so sometimes that looks like having a mustard agent applied to your skin to see what kinds of blistering happen. Sometimes it's men are put in gas chambers with gas masks and are gassed to see how well their gas masks hold up. The large scale tests are these tests on this island that the United States seizes off of Panama.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: After a survey of the Southwest Pacific Theater and the Caribbean area, San Jose Island and the [inaudible] was selected as the test ground. Since the climate and floor are similar to that which has been found in the Southwest Pacific. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: And it uses those to stage field tests. Large groups of men are asked to sort of stage mock battles and while they're doing this, planes fly over and gas them from the air. And then the question is how well did the men hold up?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And where did these soldiers come from? Who are they?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: The government is unwilling to send continental troops to be used as test subjects in San Jose Island in this way so Puerto Rican troops come. Many of them don't speak good English, they don't really understand what's happening. The men who were gassed, 60,000 men who were gassed, they experience long standing effects–many of them. Emphysema, scarring, lung damage. These men were also supposed to be doing this secretly and it only really came out in the 90s. Just how many of its own people and, you know, a good number of them Puerto Ricans, the United States had tested chemical weapons on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So Cornelius Rhoads becomes the head of the Sloan Kettering Institute and one of the forefathers of chemotherapy. This is a supremely surreal twist.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Some of the mustard agents that work as poison gases also work selectively in fighting certain kinds of cancers. And a number of doctors figured that out during the war, they put a pin in it and they say, 'after the war, let's check this out.' And so the government makes available its stock of surplus chemical weapons. Cornelius Rhoads is in charge of deciding which hospitals get it. He gives it to three hospitals and good bunch of it goes to his own hospital. And then he has a Sloan Kettering institute of which he's the head and then he has, for the rest of his career, this incredible chance. A hospital that is full of dying cancer patients who will submit to experimental treatments. And he just goes for it and just tests chemical after chemical after chemical and in doing so becomes one of the forefathers of chemotherapy.

[CLIP].

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads of the Memorial Hospital in New York. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: He's on the cover of Time magazine able to cultivate this image of himself as a cancer fighter without anyone really acknowledging that he's had this back history in Puerto Rico.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Most people didn't know the informational segregation is so complete.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah. After Rhoads dies, there is award that's given out by the American Association of Cancer Research in his honor for promising young cancer researchers. And this award is given for over 20 years before anyone who's involved, who's in the medical community and has a voice in that way, can say you might want to rethink the name of this award. Because powerful people in the United States, not just politicians, doctors too, have basically been able to think of their country as a contiguous blob and haven't really had to grapple with the parts of US history that have taken place in the territories.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, right understanding America's history of empire is vital for making sense of everything from bin Laden to The Beatles. This is On The Media.