The Obama Presidential Center Will Curate Its Own Story

( Nam Y. Huh / AP Images )

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

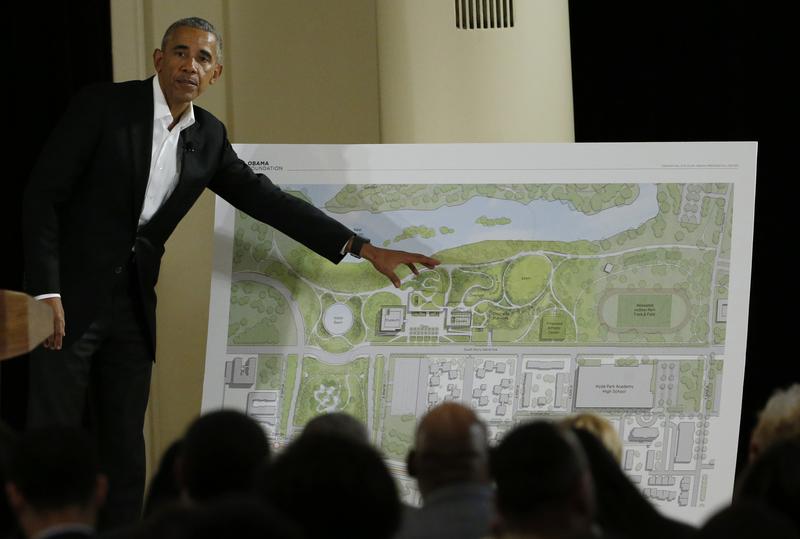

BOB GARFIELD: This is On The Media, I'm Bob Garfield. In a 1938 cartoon published by the Chicago Tribune, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt is Santa Claus stuffing a gift into his own stocking. That gift was his presidential library, the first of its kind to be run by the newly established National Archives. Every president since has given himself the very same present. But at least until now, these libraries have also been gifts to historians–one stop shopping for the documentation of 13 presidencies curated by the civil servants at the National Archive. Number 14, however, turns out to be very different. Last month we learned from the New York Times that the Obama Foundation, after building the Obama Presidential Center, will itself handle and curate the Obama papers and the museum exhibits. Tim Naftali is a professor of history and public service at New York University and former director of the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum. To Naftali, the arrangement is a conflict of interest that bodes poorly for independent history. He would know, at the Nixon Library he had to undo the politicization that came with bifurcated responsibility over the raw material.

TIM NAFTALI: Until Richard Nixon, our presidents owned their papers. Well Richard Nixon, after he resigned, had a moving van pull up to the White House to take his papers and his tapes to California. President Ford heard about this and asked his Justice Department who owns these things. And the head of the Office of Legal Counsel was somebody known as Antonin Scalia. And Antonin Scalia said the president owns them. President Ford, he didn't want to be involved in obstruction of justice. He did want people say wait a moment you allowed Nixon to destroy papers that might be relevant in future trials. So Nixon had to sign away control, temporarily, of his papers. Now when Congress saw the deal, Congress didn't like it so they passed a law called the Presidential Recordings And Materials Preservation Act. They just went in and took everything in people's desks because of the fear that some trials would not be fair trials because necessary documents would have been destroyed or withheld.

BOB GARFIELD: Now the papers are in Washington, the Nixon museum was in Southern California. One can imagine what such a thing would look like curated by his own peeps–well, you know exactly what such a thing would look like.

TIM NAFTALI: So Nixon who had been planning a presidential library before his presidency unraveled still wanted a library. So his family--he actually went to his richest friends and the family builds a library with the museum. It walks and talks like other libraries except it has no presidential material. It can't because they're still in Washington including the famous tapes. The president and the first lady decide they want to be buried there, as has become the custom for all modern presidents. So in many ways it's just like a library but it's not part of the National Archives system and it doesn't have to follow any of the norms that have been established for National Archives run presidential libraries. In the early 2000s,the family decided they didn't want to run this library anymore. They lobbied Congress to change that law that governed Nixon's materials so that the materials could be sent to California and the National Archives would run the building and therefore pay for a large percentage of its upkeep. National Archives said, 'OK we'll do this’ and then they needed a director who would run the first Nixon presidential library. That was me.

BOB GARFIELD: What did you find there?

TIM NAFTALI: Exactly what you would expect. It was a very defensive set of exhibits characterized by incomplete information. The Watergate exhibit, for example, blamed the entire investigation on the Democrats as an attempt by them to reverse the outcome of the 1972 election.

BOB GARFIELD: One never hears that anymore.

TIM NAFTALI: Right. Well, it was exactly the spinning that one would expect of a group of people who desperately wanted to change the verdict of history.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, but now there is a new sheriff in town. And, not to put too fine a point on it, your job was to revise the revisionism.

TIM NAFTALI: The challenge was to prove that a presidential library could provide an unsparing look at a failed presidency. I am concerned that we aren't talking to each other as a country. That we are reaching a point where we are losing a common baseline of facts. One of the beauties of having the federal government oversee national historical places is that, traditionally, people would believe that the facts they are getting are real. You're not supposed to engage in interpretation or wild interpretation. You give them the data, you craft the chronology, but by and large the grand theories, you leave to them. People still care what the National Weather Service says. People still care about what the National Institute of Health says. And they care about what our government scientists say about climate change. Now there are people who are trying to undermine the respect that people have for that. But I think that's a fight worth having. And I worry that without knowing it, President Obama who has opted for his museum to be private, I'm not saying it's going to look and feel like the private Nixon library that I was hired to dismantle, but that his museum is going to be private denies his own administration the source of authoritative information for public history that it should have. I mean, when I heard about this plan I was surprised because I thought that a good president would take a risk with the National Archives. He had a scandal free administration. We can disagree on what he achieved perhaps and how he went about things. But this administration, where letting the chips fall where they may, was a pretty darn good proposition and could really further the project of encouraging public history by public institutions. Institutions we all pay for and therefore we all have a stake in.

BOB GARFIELD: Now we have no evidence that he, you know, plans for some sort of hagiography. It doesn't require a whole lot of imagination to look to a Trump Presidential Library curated by, oh I don't know, Ivanka. The deep state exhibit would just be fantastic. Maybe Obama's library will be intellectually honest but the point here is that it's a slippery slope.

TIM NAFTALI: The Obama Foundation has put together an absolutely wonderful team to do the museum, but my experience is that there is a fundamental tension between the mission of a nonpartisan public institution and a private presidential legacy project. Private presidential foundations have pressures on them to always emphasize the positive part of the legacy. Because legacy could be negative as well as positive.

BOB GARFIELD: And history, they say belongs to the winners.

TIM NAFTALI: We could have a whole show about the effect of yes of who writes the history. You know, if you're like Henry Kissinger or Winston Churchill and you end up writing the first draft of your years in power, you really do shape the narrative later on. But to get back to this, so this is not a question about whether Barack Obama and his foundation are dependable stewards of history but can we not provide the American people, as one of the products of federal government, with spaces to learn about political history that are non-partisan and that they can trust. I know that the story of other presidential libraries is a mixed bag. There are some libraries that have gone to great lengths in the last 15 years to present the negative legacy if you will. The Roosevelt Library talks about the Japanese internment–it didn't before. It added a section on the Holocaust and what the US government was not doing for Jewish refugees. The Truman Library was the first to start to experiment by having open dialogue about the dropping of the bombs on Japan and having students come in and look at the options so that it was understood that one of the options could be that the president made a mistake. The Johnson library, in recent years, had started to open a debate about Vietnam–it could go further but it started a very good process. The Obama precedent would stop that and mean that that effort doesn't have to continue and the private museums will be funded by the presidents then staffed by the presidents and then their children and grandchildren can forevermore ensure that they only talk about the good things.

BOB GARFIELD: In some ways this story reflects what we saw during the Obama administration itself where the president had certain questions of overreach on executive authority on surveillance and intelligence and drone strikes and a common refrain was well, you know, 'this is us, trust us.'.

TIM NAFTALI: Transparency helps us everyday, all the time, even if it's about a matter you don't care about because it puts the government on notice that it could get caught. I think that if a president understands that his legacy could be undermined in the future that could be something that restrains them. Now, it's a maybe a naive hope, but I remember when I was putting together footnotes for the Watergate exhibit, I thought to myself for any future investigation of a presidency that engaged in abuse of power, this is the playbook. The techniques that presidents who abused power try to use were used by Richard Nixon. And there's all the evidence of them. So if you want to be ahead of the curve in this era, all you need to do is look at the materials that we put online about what Nixon tried to do. In many cases he was stopped by good government Republicans who are really heroes I think in this story. Now, isn't it great that the federal government put this online. And isn't it great that, to some extent, that history can restrain bad behavior. Now, obviously it hasn't eliminated bad behavior–look what we're living for now. But the fact that people will figure out your misdeeds, I do believe, is very healthy in society. And so it's an argument for not just day to day transparency, which is important, but historical transparency.

BOB GARFIELD: Tim, thank you.

TIM NAFTALI: Thank you Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: Tim Naftali is a professor of history and public service at New York University. Louise Bernard is the director of the museum at the Obama Presidential Center. Louise, welcome to OTM.

LOUISE BERNARD: Thank you for having me.

BOB GARFIELD: We've just heard from a historian with several worries, but I want to begin with the central one. The notion that those associated with the subject of history, shouldn't be the arbiters of that history. Fair concern?

LOUISE BERNARD: I'm an academic by training and so I do understand that particular scholarly concern. I think that all museums, regardless of whether they are run by so-called private foundations or institutions are run by the federal government, do have a curatorial point of view. There is a very particular kind of story that they are trying to tell. This is particularly central to presidential museums. The goal of which is to probe the legacy of a given president and to really think carefully about the highs and lows of that particular administration. We take public history in our educational responsibilities very seriously. We want to think about the Obama presidency in all of its complexity. That includes the highs and the lows the challenges of this particular story. The Obama Foundation is a non-profit 5013c. It's a nonpartisan foundation. We are subject to federal law to our agreements with the city of Chicago. And as with other museums, we might think about the 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York, even if run by a private foundation that story is provided in the public trust.

BOB GARFIELD: Now you mentioned curatorial point of view, but in this case we are talking about a presidency, about documents that belong to the government of the United States. And the question is whether the people who are doing the storytelling are going to be independent brokers of the history that they're beholden not to the foundation but to the public. And, you know, he who pays the piper calls the tune. Can we expect, for example, that there will be a museum exhibit on drone strikes? Can we expect one about the prosecution of journalists or of the Syria red line that wasn't a red line and, not to put too fine a point on it, can the foundation be trusted to be honest brokers?

LOUISE BERNARD: Yes, we work very closely with the National Archives and Records Administration. And so we followed their standards but we also engage with a group of historians and museum experts. We have intentionally built a very careful process of review and approval to really engage people in terms of feedback and critique. In terms of your questions about very specific stories, we're still in the process of developing the content. Yes, there has to be a way of telling all sides of a very complex topic in a fair manner, in a judicial manner. It's still very recent history. There's still much to be understood about the Obama administration and its legacy. And so we all want to be an ongoing dialogue with historians and other scholars, other researcher around the story that were telling.

BOB GARFIELD: I want to ask you about precedent setting. Maybe the Obama library, as you constructed, is going to play it straight historically. But, you know, what about the Trump presidential library? With this precedent established, maybe we can trust you, but who's to say we can trust them?

LOUISE BERNARD: It's difficult for me to speak to kind of hypotheticals. We're working very closely and very collaboratively with the National Archives and Records Administration, with NARA, with the federal government to understand an evolving model.

BOB GARFIELD: While--well, overall levels of trust in the federal government have been diminishing, lately plummeting, there were certain things that the public still does trust about the government, still wishes for the government to be the arbiter of. NASA, they trust the National Weather Service, they trusts the National Archives as an independent broker of the documentary history of the republic. Does the Obama library's organization defy or even erode the trust?

LOUISE BERNARD: For other presidential libraries or presidential centers, there has long been a very thoughtful relationship between the private foundations and NARA. So we're continuing that work, at the same time placing a particular emphasis on digitization because that is the way forward.

BOB GARFIELD: Am I being too reductive to ask you if you're just saying, 'no really just just trust us.'.

LOUISE BERNARD: It's more than that. It's saying that we are accountable to the deep scholarly work of historiography. Of course, we may be judged in various ways. Any scholar who produces a book is open to critique in terms of a particular thesis or approach. The storytelling at the heart of a museum is also one that will engage a range of interlocutors. And we also think about the programming work, the educational work that will bring the museum to life. That is also a point in which people can weigh in, can provide their own reflections and commentary. So it's an ongoing dialogue and I think dialogue is also the heart of scholarship. It is a living thing and the museum is a living thing. Its a living entity. There will be space for people to share their points of view accordingly. You know, the pushback that we have received, the questions that are being asked will only places in a kind of a better position down the line. This is the engagement that needs to take place.

BOB GARFIELD: I'm going to suspend the interrogation and ask you as someone who is--who gets to build a library from scratch, what cool stuff he may have in mind?

LOUISE BERNARD: We have a wonderful opportunity to reflect back on the power and possibility of that watershed campaign moment 2007-2008. So you can imagine all of the amazing ephemera that many people have in their attics, in their garage–whether it was a handmade banner or a T-shirt or a button. And then we also think about key items that shows an artifact like one of President Obama's signing pens. There will be a huge amount of interest around the first lady's dresses not only because they were beautiful objects but also because of the stories that they tell. She was really attuned to the idea of uplifting designers of color, young people and also connecting the dresses that she wore, the sartorial diplomacy, to education. So there's a range of material.

BOB GARFIELD: Dude sartorial diplomacy, ready? The beige suit.

LOUISE BERNARD: We will be happy to tell a story about the beige suit I'm sure.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Louise, thank you very much.

LOUISE BERNARD: Thank you so much Bob. It was a pleasure to speak with you.

BOB GARFIELD: Louise Bernard is the director of the museum at the forthcoming Obama Presidential Center.

BOB GARFIELD: Coming up the history of segregation. Trigger a warning: it is grotesque. This is On The Media.