New Strides in West Virginia's Old Labor Movement

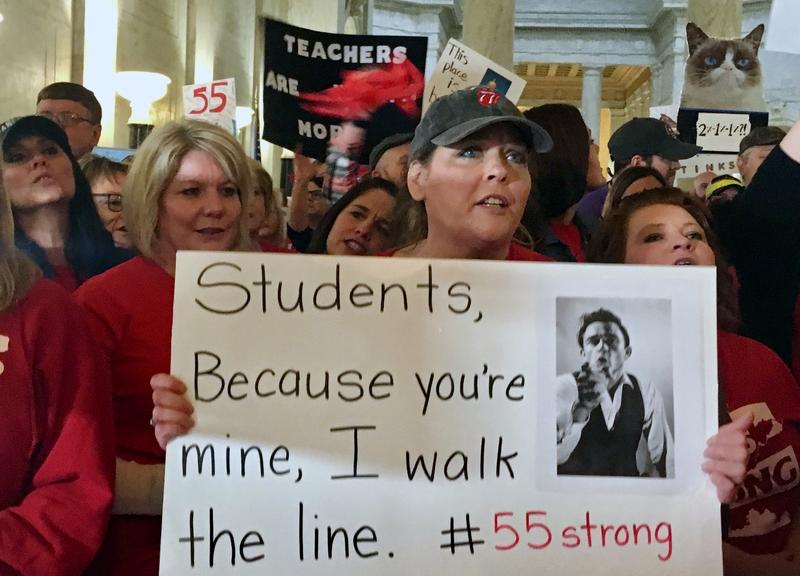

( John Raby / AP Images )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield. This week, a blast from the past.

[CLIP/SOUND OF RALLIERS CHANTING]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Teachers rallied outside the State Capitol yesterday. They have shut down West Virginia's classrooms, demanding higher wages. Teacher pay in West Virginia is among the lowest in the nation. A demand to meet the governor has so far been denied.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: A strike, in West Virginia in 2018? It was like that 19th century message in a bottle that floated up this week on an Australian beach, a relic from a different time. Sarah Jaffe is a journalist and cohost of the Belabored podcast at Dissent Magazine. Sarah, welcome to the show.

SARAH JAFFE: Thanks for having me.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, we live in a world of wealth disparity and corporate plutocrats and so-called “right-to-work” states and over the last 40 or 50 years, the steady erosion of worker rights --

SARAH JAFFE: Yes.

BOB GARFIELD: -- especially for public employees. And then this erupts!

SARAH JAFFE: Yeah.

BOB GARFIELD: A wildcat strike, no less. Where did this come from?

SARAH JAFFE: The teachers in West Virginia are the 48th or 49th worst paid in the country, and they also don't have legal collective bargaining, which means that their unions are technically associations. They don't actually bargain with the school district on behalf of the teachers. They mostly get what they do through lobbying for legislation. So what’s happened in West Virginia, like what’s happened in many states, especially, since the 2008 financial crisis is that state budgets are strapped and they're taking them out on public services. Public employees are seeing wage cuts, they’re seeing cuts to their health insurance, and they finally had enough.

And so, the interesting thing about this, of course, is, as you said, wildcat strike, that this is not something that has a formal process for like a contract ends and there's a strike vote, which is normally how we see teacher strikes or any other strike. This, instead, was teachers talking to each other and saying, we’ve had enough and we’re going to do something about it. And that began in three of the historic coal counties, Mingo County, Logan County and Wyoming County. They first went out on strike, closed the entire school districts down in those counties, went to the capitol. And the rest of the state thought it looked like fun --

BOB GARFIELD: Mm.

SARAH JAFFE: -- and joined them.

BOB GARFIELD: And this actually harkens back to the very beginning of the labor movement in this country.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

SARAH JAFFE: Oh yeah, oh yeah.

BOB GARFIELD: It wasn't negotiated and then eventually strikes emerged.

SARAH JAFFE: Right.

BOB GARFIELD: Oh, no, no, it was the other way around.

SARAH JAFFE: Right, [LAUGHS] exactly. We got strikes for a long time and then we got labor law and collective bargaining and things like that. Collective bargaining was always the compromise. It was the thing that was written into law starting in 1935 to end these big strikes that, particularly in places like West Virginia, were actually very violent at the time.

BOB GARFIELD: The teachers nominally won.

SARAH JAFFE: Right.

BOB GARFIELD: They got a 5% pay raise, their first in four years.

SARAH JAFFE: Right.

BOB GARFIELD: But at the expense of other public spending, including Medicaid.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

SARAH JAFFE: Right, that’s the question. The cuts are not written in stone, yet. What is written in stone is a 5% pay raise for not just the teachers, not just the school employees but every single public sector worker in the state of West Virginia, which is a lot of people. But the real question is, where is the money going to come from? And a lot of the teachers were arguing that the energy companies that extract various forms of fossil fuels from the state should pay higher taxes. So that’s the next fight. That's the real question, going forward: How much of a win will this turn out to be? And that, we don’t know.

BOB GARFIELD: And how much momentum there really is.

SARAH JAFFE: Yeah.

BOB GARFIELD: I mean, on the one hand, the teachers have shown that they [LAUGHS] can surmount the right-to-work obstacles and their diminishing legal protections.

SARAH JAFFE: Right.

BOB GARFIELD: But, at the same time, there's a Supreme Court case called Janus v. the Government Employees Union which could allow non-union workers to refuse to pay the fees they've had to pay unions in exchange for the benefits that come in the union- negotiated contracts, right?

SARAH JAFFE: Labor law in the US, it started again in 1935, gave unions the right to collect a fee from the workers that they represent because it requires them to represent everyone in a bargaining unit that has voted for a union. So even the workers who don't vote for the union still get the protections, the higher wages, the better health insurance that the union bargains for. And for that, the union is entitled to some sort of fee.

BOB GARFIELD: The premise being --

SARAH JAFFE: Right.

BOB GARFIELD: -- that otherwise everybody could get a free ride.

SARAH JAFFE: Exactly.

BOB GARFIELD: They wouldn’t join the union --

SARAH JAFFE: Right, right --

BOB GARFIELD: -- but they’d be the beneficiaries of whatever that union was able to negotiate.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

SARAH JAFFE: Exactly, right. So when you have a right-to-work law, what it does is it allows people to get all those benefits for free and it allows them to defund the union. And so, what we’re seeing now is this steady chipping away, right? We’ve seen right to work introduced in places like Michigan, Wisconsin, places that were at the heart of the industrial economy in this country. Now the unions are being slowly gutted.

And when people are already not getting raises, it can be really compelling to somebody who hasn’t had a raise in six years to say, like, well, why are you paying union dues? The Supreme Court already made right to work the law of the land for home healthcare in 2014, with the Harris v. Quinn case. And so, that was sort of the setup for what’s probably going to happen with Janus.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, I daresay neither Janus nor Harris v. Quinn on top-of-mind legal battles. It didn’t require Stormy Daniels to knock ‘em off of cable news. They weren’t there already. Labor has already been marginalized. What else has gone missing in an environment where journalism has kind of triaged labor reporting out of the picture?

SARAH JAFFE: I think there’s actually a direct line from not talking about labor to talking about working people the way a lot of these Trump country articles talk about them. When you end up with reporters sort of going on safari to where the “poors” live and writing these stories about people who voted for Trump and talking about them as if they are some sort of incomprehensible other species, that actually comes from a press that is disconnected from working-class people and their lives. And that’s a really big problem, and it's not just a problem of, like, are you covering the struggles of a union to win a bargaining contract, but are you covering the lives of working people the same way we’re covering the lives of celebrities or whoever it was that is suing Donald Trump or being sued by Donald Trump, or whatever?

BOB GARFIELD: And so, West Virginia, wildcat strike, [LAUGHS] heroic teachers getting out from under the heel of the man, sort of.

SARAH JAFFE: [LAUGHS]

BOB GARFIELD: Is there any part of you that believes that this could be an inflection point, that it will restore labor to the national conversations?

SARAH JAFFE: We’re in the middle of a shift in our understanding of how people relate to the economy. When you look at something like Bernie Sanders, he wins a bunch of states, including these very same states -- West Virginia, Wisconsin, Michigan -- where working people are trying desperately to figure out how to fight back, and often getting stomped on. And there is no doubt that when people see strike people go on strike, you can look at the strike frequency chart that just plunged after 1981 when Ronald Reagan broke the Air Traffic Controllers Union, strike frequency has just dropped off.

But after 2012, the Chicago teachers, teachers have been going on strike, and teachers have also been threatening to go on strike, taking strike votes and winning right up to the minute. The week before the West Virginia teachers went on strike, the St. Paul Minnesota Teachers Union took a strike vote, went up to midnight the night before their strike deadline, and they would have been on the picket lines on Tuesday morning, and got most of their demands met.

And, again, this is what we lose when we don’t sort of have labor as a beat, is you don’t see the context, you just see the, oh my God, the teachers are on strike in West Virginia. But you don't see the different places where things have been changing more incrementally all along.

BOB GARFIELD: Sarah, thank you very much.

SARAH JAFFE: Thank you!

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Sarah Jaffe is a journalist and cohost of the Belabored broadcast at Dissent Magazine. Her book is called, Necessary Trouble.

By Wednesday, the strike was over and the teachers were back in their classrooms. But with the West Virginia wildcat teachers strike bringing renewed attention to Appalachia, commentators suddenly are reframing the character of the region.

[CLIP]:

MAN: Lo and behold, the solution is give all the money to corporations and, and, and we’ll worry about you guys later. I love that the teachers are saying, no, you’ll worry about us right-the-hell-now! Okay, that’s supposed to be the fighting spirit of West Virginia.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Which is a far cry from the conventional wisdom in the wake of the 2016 election.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: If you go to West Virginia, Trump land --

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Coal country is now Trump country.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: The Appalachian voters chose Trump.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: This time last year, we spoke with Elizabeth Catte, a writer and historian from East Tennessee, and author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia.

ELIZABETH CATTE: Yeah, so even before the election took place, these localities in West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky “coal country” were identified quite unambiguously as “Trump country.” Every prestige publication, from the New Yorker to Vanity Fair, had a profile about sort of down-and-out white voters.

BOB GARFIELD: In the past century, the narrative about West Virginia workers has fluctuated pretty dramatically from the anti-labor violence and exploitation of the early 1900s to the rise of big labor in the ‘50s to the age of Trump, and the caricature of self-defeating conservative politics among those most affected by globalism, climate change and advancements in technology. But suddenly, this new narrative, or resurrected one, resistance. So we turn, once again, to Elizabath Catte, who says, that at least as far as the coverage goes, things are looking up.

ELIZABETH CATTE: The national coverage of this strike has been tremendous. I think that the national media is doing all the things that I wish they had done in 2016. They're getting into political nuances, poking holes at West Virginia and Appalachia's messy politics. They’re on the ground interviewing many types of people, from service workers to teachers to old union bosses. Everyone seems to have a voice in this conversation that's happening now. Smaller progressive outlets have joined national media to kind of shape coverage. So it's been really, really fantastic.

But one thing I would point out, the last time that we spoke I think I said that the narrative of Appalachia swings like a pendulum, that we’re either heroes or heretics. And last time we spoke, we were definitely the heretics. Now we’re the heroes. But we still have to watch out for that balance that needs to come through the coverage of the region.

BOB GARFIELD: This time, you’re satisfied with the coverage. Does this tell us about the media’s performance or does this actually just tell us about you?

ELIZABETH CATTE: Well, I think that's a fair question. I'm, obviously, going to admit my bias here and say that the coverage that’s coming out of West Virginia is more aligned to my personal politics so, of course, I am inclined to be little bit more generous, and that's totally fair to point that out.

But based on conversations that I’ve had with people in the media surrounding the release of my book, I think there was a reckoning that happened maybe a little bit behind the scenes and among certain media outlets that the coverage of Appalachia that came out of the region in the 2016 presidential election was a little bit skewed, a little bit unfair. There were some mea culpas going around. And so, I'm hopeful that this points to a broader change in the national conversations that people are willing to have about the region.

BOB GARFIELD: On the subject of caricatures, the data from the election and the polling data for the ensuing year shows that there is this class of white women who are still solidly in Trump's camp, in Appalachia and elsewhere in the red states, and I, I'm wondering if that flies in the face of what's happening with the West Virginia teachers or whether we need to simply hold two apparently [LAUGHS] opposing ideas in our head at the same time.

ELIZABETH CATTE: It’s going to be really tempting to seize on a narrative that says, this is the resistance, this is the political comeuppance for the Trump era. And the reality is, is these are Trump voters, these are Clinton voters, these are people who don't do a lot of civic engagement. All types are represented in this movement, and we can't really assign them a dominant political narrative.

So I think it’s good to keep in mind that we still want to bring a lot of nuance to these narratives and stories that we’re going to tell about the region.

BOB GARFIELD: I have to say that this whole episode is giving me a, a sense of déjà vu, not that I was around in the ‘20s during the mine wars and the clashes between mine workers and the thugs employed by Big Coal but because I know that is very much a formative part of West Virginia history. Are we just -- - [LAUGHS] excuse the obvious metaphor -- but mining a vein of West Virginia culture that never really disappeared?

ELIZABETH CATTE: I think that's fair, to look at the way that history has informed the way that teachers and public workers and West Virginians, in general, at this moment, are seeing their place in the world. They're using messaging that calls out to the history of labor struggles in the state. They’re wearing red bandannas. They’re giving deference to teachers from the Southern coal camps, which were the hardest hit by labor struggles and, and coal extraction.

BOB GARFIELD: Red bandannas, they’re iconic, why?

ELIZABETH CATTE: Red bandanas were some of the only things that miners could purchase with their earned money that wasn't a part of the company store ecosystem. So these are the kinds of messaging that are taking place in the state and as teachers went about their strike actions.

But it’s important to realize that this is not only the history of the state but also the histories of their families. And so, these women who are leading the strike -- 75% of teachers are, are women -- they’re recalling their grandfathers, their uncles, they’re recalling their mothers and aunts who were participants in the 1990 teacher strikes, as well. So absolutely, it's a vein of history that never went away, but it never went away because it's in people's families, as well.

BOB GARFIELD: Is it ingrained in the West Virginia character? Are these simply political heirlooms or are they just ancient grudges that are, once again, relevant?

ELIZABETH CATTE: What I see is really relevant to the way that all this history is connecting in regards that this strike is the tension over who keeps the state alive. And politicians and their corporate allies are going to say it’s energy companies, it’s the fossil fuel industry, it’s coal; now it’s natural gas. Workers are saying that we are the ones that keep the state alive. It’s our labor, it's our bodies that keeps these politicians and these corporations in power. So that is really a tension that has not changed from the time of the mine wars to present day. Workers are still trying to do the best they can in a system that is really indulgent of corporate largess.

BOB GARFIELD: We spoke about pendulums. The right-to-work movement happened to coincide very neatly with the Southern strategy and the gradual conversion of Dixiecrats into conservative Republicans. And those politics have spread around the county, not just in the South and in Appalachia but to Wisconsin, for example. Do you believe that this suggests that the pendulum is going to swing beyond West Virginia to revive the labor movement and resistance against corporate America and “the man”?

ELIZABETH CATTE: It’s fascinating to me. In 2016, we saw a narrative where the nation was terrified that something that was happening in Appalachia and West Virginia was going to leak out and contaminate the rest of the country. And, of course, that was Trumpism. Now, people are quite excited for something that's happening in our region to spread beyond its borders. Igniting a wildfire is the metaphor used. So people are incredibly hopeful that we might see the rise of a new labor movement that finds a way to navigate around these really oppressive right-to-work laws. They’re hoping that it spreads to other states. Like, Oklahoma, Arizona and Kentucky are now all talking through potential strike actions. So that’s where we are.

And, as somebody who, you know, thinks in terms of pendulums, I have enjoyed the way that -- the direction that it’s swung now but I am also skeptical that there's an intense and cohesive set of politics behind this momentum.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: So far.

ELIZABETH CATTE: So far.

BOB GARFIELD: Elizabeth, thank you very much.

ELIZABETH CATTE: Thank you so much.

BOB GARFIELD: Historian Elizabeth Catte is the author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia.

Coming up, still more of what the coastal elites don't understand about working class America and its music. This is On the Media.