BOB GARFIELD: Robert McChesney is professor of communication at the University of Illinois. He has devoted his career to studying the effects of big media. Bob, welcome to the show.

ROBERT McCHESNEY: My pleasure to be here.

BOB GARFIELD: First, I want to go back down memory lane and discuss the question of media concentration, as you first studied it and wrote about it decades ago, in the old analog days.

ROBERT McCHESNEY: What took place in the 70s, 80s and 90s was the consolidation of what were, at one time, several hundred independent, oftentimes competitive media into a system dominated by, you know, six or seven giant conglomerates and then another two dozen or so smaller-scale conglomerates.

BOB GARFIELD: Then what happened was the Internet came along and, at least seemed for [LAUGHS] about 20 years to make the fears seem less relevant because, after all, the Internet was going to be the ultimate democratization, millions and millions and millions of independent voices all accessible from anywhere in the world.

ROBERT McCHESNEY: And, in fact, in the mid-1990s, John Perry Barlow, the lyricist for the Grateful Dead who became sort of a famous cyber democracy advocate, wrote a manifesto in which he said, we don’t have to worry about the Rupert Murdochs and the Time Warners of the world because all they’re doing is rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. The iceberg they’re about to hit is the Internet with its tens of millions, even billions of websites, basically making media conglomerates irrelevant in the near future. And that was a common belief, I think, in the 1990s. That was the conviction.

There's been an element of truth to it to the extent that the Internet has revolutionized our lives, and it means that it gives us access to a broad range of information that would have been unthinkable 25 years ago or 20 years ago that we get today and we take for granted.

The downside was that what the Internet also did is it removed the business model for commercial journalism upon which journalism had been based for 125 years in the United States, and it offered nothing to replace it. And so, that crisis has grown much more severe as a result of the Internet; it hasn't been solved by the Internet.

BOB GARFIELD: Do your concerns from the 70s and 80s, do they seem trifling now? Do they seem quaint?

ROBERT McCHESNEY: Well, you know, they seem really of a piece. They’re, they’re just the earlier stage of where we are now. The media giants, the conglomerates that were built up by the end of the 20th century, they’re still around today – CBS, News Corporation, Disney. They were sort of like the equivalent of the Ozark Mountains.

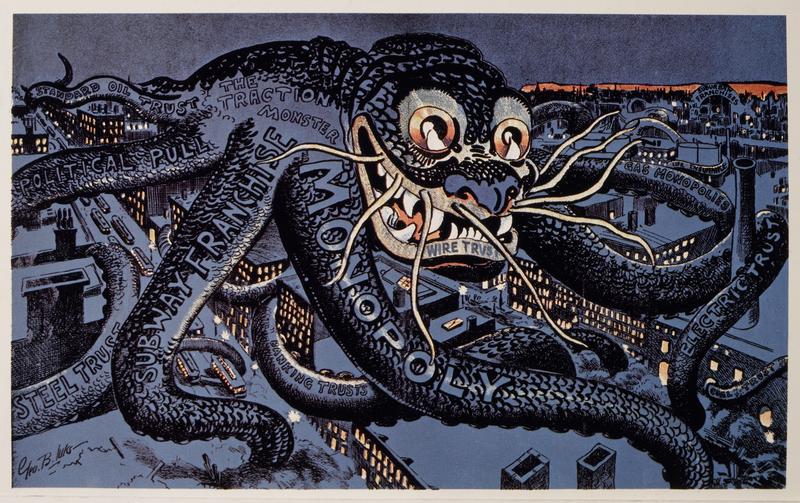

Now, we’re talking about the largest companies that dominate the whole Internet economy. They’re the most valuable companies in the world today – Google, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook. These companies are much more like the Himalayas, compared to the Ozarks. They, they completely overwhelm our society, and they’re very much monopolies in the classic sense that Standard Oil was a monopoly under John D. Rockefeller, in that they really do not have to fear for going out of business and they can control how much competition they have by how serious they want to dominate their market. And they let enough competition in as needed to protect their profitability. And it creates a fundamental problem for society.

What do you do when you have these massive private firms that dominate the economy and have the resources to dominate the government and influence what the government does to their benefit? And this has been a recurring problem in the United States since the Gilded Age of the late 19th century. And now it’s come back with a vengeance today in a way completely unlike anything we saw throughout the 20th century.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, you said the M word, and the US government broke up Standard Oil on antitrust grounds. Is that the remedy for the concentration of power on the Internet that we’re witnessing now?

ROBERT McCHESNEY: It might be, but there’s also the argument – and this is an argument made, ironically, by conservative economists more than liberal and left-wing economists, including Henry Simons who was Milton Friedman's mentor at the University of Chicago - that when you get a, a private monopoly that’s so large, it – that, that you can’t break it up effectively ‘cause it’ll return to becoming a monopoly again within a few years, what you have to do is take it out of the market system and make it some sort of post office or government-run or municipally-run enterprise, so that it’s not dominating other smaller businesses, it’s not dominating consumers and, worst of all, it's not dominating the government through its sort of power over legislators and government decisions.

BOB GARFIELD: You’re saying nationalizing Facebook, or have I missed something there?

ROBERT McCHESNEY: Well, “nationalizing” is a loaded word. That term is suggesting you’ve got a central committee, and so on, speaking in a foreign accent coming in and crudely bossing everyone around and is completely unaccountable. But you can have systems that are nonprofit that are run, that are accountable and that are effective. The BBC is nationalized, right? The US Post Office is nationalized. Public schools in most cities are municipalized.

And Simons’ point, as a conservative economist, was that if you allow private monopolies to go really large, they will distort capitalism, the system he loved, and make it incapable of being a functional system because they will dominate the whole economy and the government and turn the governance very corrupt. I think he’s raising issues that we’ve got to take very seriously. I’m going back to Louis Brandeis of the Supreme Court, to Clarence Darrow in the great battles over the railroads and Standard Oil. And we can’t put our head in the sand about them. We’re gonna have to deal with them at some point.

BOB GARFIELD: Well, let's just say that, without putting our head in the sand, that it – it’s a political nonstarter for the next decade at least to really consider taking these juggernauts of Silicon Valley and somehow rendering them into public utilities. Is there another way to approach media concentration that is more politically practical?

ROBERT McCHESNEY: Yeah, there is, and I agree with you. The idea is not politically feasible at all in our times, in our media times, for the reason Simons and Brandeis outline, which is these companies have immense political power with both parties, and so challenging them is going to be extraordinarily difficult. That doesn't mean you can't do anything. We can enforce network neutrality on the cartel that offers Internet service provision, on Comcast, AT&T and Verizon. They still keep all their money, their profits, their power but they can’t abuse their power to such an extent that they can discriminate against websites. We’ve stopped that.

And there are a number of other measures we can do against surveillance, for privacy that would keep the system intact but also protect our interests. And then finally, for the issue that, Bob, you and I both care about so much, we can do a lot to promote and extend journalism that these companies could then help us, you know, distribute the material through their various algorithms and services. They are not an impediment to that, whatsoever.

BOB GARFIELD: Are, are you suggesting that they can and should defeat the central populism of the newsfeed, giving us more and more of the, the yummy stuff that we like to consume and force-feed us broccoli and green vegetables and legislative votes on redistricting and so forth?

ROBERT McCHESNEY: The last thing I want is Facebook or any other company patronizing us, and nor do I want someone enforcing that on those companies either. And I also am a big believer that people will demand information as it’s important to the world they see and to the world they want to be in. And part of the reason why it seems like people would regard information about the economy or politics as to be broccoli, as opposed to apple pie or pizza, is that they feel somewhat powerless, so it’s sort of like boring information that doesn't really have any value to them ‘cause they have no control over those sort of decisions for that world. So it’s better to learn about the New England Patriots’ defensive secondary than it is about, you know, trade policy. And I think as people get more interested in politics, the, the taste grows and they’ll start demanding more information of value to them.

BOB GARFIELD: Public policy is an acquired taste. You don't actually have any evidence of that, have you?

ROBERT McCHESNEY: Yeah, I do. I think it's all around us right now. It’s one of the most interesting stories of our times right now, is that there’s been a real surge of interest in politics among young people in this country in the last – it’s grown gradually over the last 15 years but especially in the last 3 to 5 years, much greater than what I saw when I was in the - a young person in the late 70s or in the 80s or 90s. And as this happens, there’s a lot more interest in learning more about the world. And so, I think you see that on social media. I’m, I’m experiencing it. I see it in my classroom. So I think we’re at a moment right now where there is actually a genuine hunger to learn more about the world and a frustration with the lack of information people are getting.

BOB GARFIELD: Bob, thank you so much.

ROBERT McCHESNEY: My great pleasure.

BOB GARFIELD: Robert McChesney is an author and professor of communication at the University of Illinois.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Coming up, accountability the analog way. This is On the Media.