Jane Mayer on the Rise of Conservative Orthodoxy

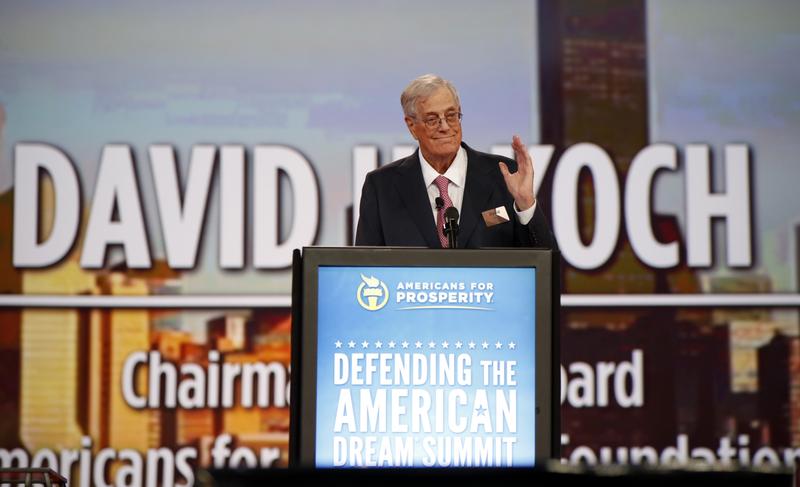

( Associated Press / AP Images )

BOB GARFIELD: After the House vote to repeal and replace Obamacare, the president and House Speaker Paul Ryan can both now claim they've kept their promise to deliver Americans from the tyranny of the Nanny State into the efficient hands of the free market.

[CLIP]:

HOUSE SPEAKER PAUL RYAN: …a real vibrant marketplace with competition and lower premiums for families. That's what the American Health Care Act is all about.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: The vote was also, at least superficially, a triumph for conservative orthodoxy, small government over big, low taxes over high, states’ rights over national government, and so on. But that orthodoxy did not spring fully formed into post-World War II America. It was painstakingly constructed over the decades as a means to achieve the ultimate goal, the preservation of capital for really rich people.

Jane Mayer is a staff writer at The New Yorker and author of Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right.

JANE MAYER: A lot of what you think of as the modern-day machinery of right-wing ideology all goes back to the imposition of an income tax in this country, which happens sort of around 1916. There was a great uproar on the part of some of the wealthiest families in the country who didn't want to pay income taxes, and a deal was struck. Congress told these families, if you give your money away to charitable organizations, we will give you a tax break but the gifts have to be in the public's good. And a lot of what you're looking at now, think tanks and, and much else in politics, actually, is set up a sort of an arm of philanthropy.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, we’re speaking of the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation and similar philanthropically-funded organizations.

JANE MAYER: Absolutely. The Rockefeller Foundation is the granddaddy of them all. When the Rockefeller family wanted to set up its own personal family foundation, it was incredibly controversial. There was bipartisan opposition from across the board. All of these congressmen and senators said, this is an undemocratic thing, to have a rich family be able to spend its money on public policy and get a tax deduction. They saw foundations as unaccountable to anybody but the super rich and playing a undemocratic role in the midst of our democratic society.

BOB GARFIELD: Were these big capitalists, indeed, figuring out a way to influence public policy?

JANE MAYER: Well, the first step towards politicized philanthropy, in the view of many people, was the Ford Foundation, and it wasn't for quite some time. It was really in the 1960s when it got involved in education policy, all tied up with teachers’ unions and with integration and all those issues, and the right wing made a lot of noise about it and the Ford Foundation backed off. But the right wing also learned from it and soon started pouring money into its own philanthropies that became intensely political.

BOB GARFIELD: The thrust of this conversation is going to be on the Heritage Foundation that undertakes to understand and promote conservative policy and ideology. But it wasn't the first think tank. Who were the first think tanks?

JANE MAYER: The early think tanks were Brookings, which was actually founded by a Republican who wanted explicitly to have people of different points of views gathered together to do scholarly work and try to solve society's problems. He wanted many points of view. The Russell Sage Foundation was also quite early. They were trying to put the best minds to work to solve society's problems.

BOB GARFIELD: Non-ideological, nonpartisan, presumably legitimate academic scholarship.

JANE MAYER: Right. And they thought of themselves very much as neutral and apolitical, really. Many of the solutions that the earlier think tanks, including Brookings, came up with involved answers that involved government activism of some sort or another. So when the right finally weighs in with its own version, they attacked these organizations as being liberal. But the organizations were not set up to be liberal or anything else, from their own standpoint.

BOB GARFIELD: So to the extent that the political right believed that think tanks like the Brookings Institution had aligned with progressive ideas, this gives us Heritage.

JANE MAYER: By about 1971, some of the leaders of the biggest businesses in America became alarmed. They watched the anti-Vietnam War movement taking on the companies that were involved in the defense industry, the consumer movement of Ralph Nader and the environmental movement that was beginning to call for all kinds of regulations on pollution. And you get this kind of call to arms by Lewis Powell, who was then a lawyer from Richmond; he wasn't yet on the Supreme Court. He wrote a paper for the Chamber of Commerce and he said, big business, if you don't get organized, we’re going to lose our way of life. The enemy is not the kids who are on the streets protesting, it's not hippies or yippies. The enemy is elite public opinion. And if we want to fight back, we have to change the way the elite public opinion is formed in this country, all of the instruments that form public opinion, meaning the media, the pulpits, academia, science, the courts and public policy. So the creation of right-wing think tanks, starting in the late 1970s, was an answer to Lewis Powell's call to arms.

The people who set up the Heritage Foundation were literally talking about this Lewis Powell memo and saying, we've got to do something, we’ve got to spend money, we've got to fight back. Joseph Coors, who was heir to a brewing company in Colorado, sent a letter to his senator, Gordon Allott and said, I've got money, how do I spend it? And an aide who was working for Allott saw this letter, and his name was Paul Weyrich, and he was one of the two founders of the Heritage Foundation and he said, I've got an idea. We’re going to set up this think tank.

BOB GARFIELD: And Richard Mellon Scaife, the archconservative Pittsburgh billionaire, came in at approximately the same time with approximately the same idea.

JANE MAYER: That's absolutely right. Coors came in with the first funding for the Heritage Foundation. Coors was a John Birch Society member and so coming from the far right, and people said at Heritage, he gives six packs but Richard Mellon Scaife gives cases. He was just overwhelmingly the, the major funder of the early Heritage Foundation. I think he gave $23 million in its, its first 10 years or so, at that time, just a phenomenal amount of money.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, there’s two ways for an institution that wants to influence policy to behave. One is to do bona fide scholarship and that scholarship should inform recommendations for public policy. Another way is to determine what public policy you want and then kind of manufacture the scholarship to suit. Is that what Heritage did?

JANE MAYER: Right. Eric Wanner, who was the chairman of the Russell Sage Foundation, said Heritage turned the model on its head. When the Heritage Foundation was started, there’s sort of a origination myth. Edwin Feulner, Jr., who was one of the cofounders and is now coming back to run it again, he was working in Congress as an aide and he and Paul Weyrich, his friend, there was some kind of legislation that they were unhappy with, and the current think tanks that had existed at the time only weighed in after the fact. The American Enterprise Institute was a conservative think tank that already existed but it didn't feel its place was to get involved and lobby the congressmen before the legislation was voted on. And these two young aides thought, well, that’s stupid, you have no effect if you're not gonna get in the congressmen's faces before they take the vote. And so, when they founded the Heritage Foundation, it was explicitly to lobby. They weren’t just a think tank. They were, as they called themselves, a “do tank.” It’s it's kind of an unfortunate [LAUGHS] term [ ? ],

BOB GARFIELD: [LAUGHS] You know, I have a friend who was, back in the day, a Soviet émigré, and back in Lithuania, in Soviet Lithuania, he was an econometrician. He had to fill his model with input-output data that was entirely invented by Communist bureaucrats.

[MAYER LAUGHS]

He was told what the outcome should be, then had to come up with the raw data to produce that outcome. Is it that bad?

JANE MAYER: People like Steve Clemons, who worked in sort of conservative think tank worlds, and David Brock, who was originally on the right and is now on the left but who was inside those think tanks, what these people who were first-hand observers inside would talk about is that the scholarship was corrupted, and they do describe that.

Now, I mean, I have to say, I’m not willing to think the liberal side has all the answers and that it's always academically honest, either. I'm sure that these things happen on all sides. It’s just that the think tanks on the right were built for political purposes. One of the areas where this matters the most, of course, is when it comes to issues like global warming, where there’s so much money on one side of the scholarship. The whole fossil fuel industry is trying to fund research that says global warming is either not real or, if it's real, it's not bad and nobody should do anything about it because the solutions are worse than the problems. There are just endless amounts of that kind of phony science, and it follows very much in the wake of the same kind of phony science that was paid for by the tobacco industry, which for years said that cancer is not caused by smoking.

You would out of these right-wing think tanks theories like supply-side economics, which claimed that if you cut everybody's taxes more money will come into the government, somehow because the economy will thrive. Well, I mean, we’ve had a few experiments in it now, and it hasn't worked that way.

BOB GARFIELD: And yet, remains an article of faith in conservative thought.

JANE MAYER: It's a zombie theory that can't be killed –

[BOB LAUGHS]

- because it keeps being revived by these think tanks, and also it serves the purposes of the donors to the think tanks.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, so let's just say I'm really mad about the Civil Rights Act and the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act and I want to build myself a great influence machine, how do I do it?

JANE MAYER: Well, that’s pretty much the question that faced Charles and David Koch, among others. And they were engineers who had graduated with both undergraduate and graduate degrees from MIT. And they looked at taking over American politics as a great engineering challenge, and they decided you couldn't really rely on just funding candidates ‘cause the candidates are just going to spout sort of conventional wisdom. And so, what they set out to do was change what the conventional wisdom in the country was by setting up think tanks, funding intellectuals, funding academic centers – they now fund something like 350 of them in universities and colleges across the country - funding media organizations and disputing science by coming up with counter-science studies. All of that is how you do it, and that's really how they did it.

BOB GARFIELD: I think it might be instructive to look at just one little point within the ecosystem to see how interconnected it all is. There was a time when Dartmouth was just one of the Ivy League colleges. Then there was a strategic investment in academic centers at Dartmouth, which became one of the hotbeds of conservative thinking, at least on the East Coast.

JANE MAYER: Dartmouth is a good example. The Dartmouth Review, in particular, started getting money from outside organizations, and it was an on-campus publication that became kind of an incubator for many of the more famous conservative propagandists and writers right now. Dinesh D’Souza came out of there and Laura Ingraham and many others. It was a directed effort by funders on the right to try to have centers in the universities that would cultivate conservatives, that would then go on and become leaders.

BOB GARFIELD: In your book, you quote Steve Wasserman, who is editor-at-large at Yale University Press, one of the bastions, I suppose, of the liberal coastal elites, [LAUGHS] lamenting that wealthy liberal donors simply aren't as keen to make intellectual investments as the right-wingers.

JANE MAYER: Well, I thought that was a really good point. You have to give conservatives some credit here. They funded an intellectual movement and they did it over four years. They played a long game, funding people writing books, people like Charles Murray, people like George Gilder. And the Democrats were much more short term in their thinking. They maybe put money into particular political races but they didn't really look at this whole thing as funding an infrastructure that was built to last and change the way the country thinks.

BOB GARFIELD: Because politics follows the money, it goes after the money, [LAUGHS] it secures the money and it does the bidding of the money, we now have a, a legislature that represents the interests of this dark money. Talk about being out of touch, it’s not the media, it’s the actual Congress that is out of touch with the thinking of mainstream America. Is that observation correct?

JANE MAYER: I think it is, in many ways. I would argue that part of the reason Trump got elected was he went in a different direction from what many of these think thanks, for instance, have been pushing. They were pushing free trade, open immigration and they were also pushing for privatization of things like Social Security. And, if you remember, I don’t know if he’ll stick to his promises but he promised to strengthen Social Security, rather than gutting it. He talked about infrastructure spending, which is very popular with voters and very unpopular with big right-wing donors who want to shrink big government, as they see it. So yeah, Trump saw an opening there and I would say he exploited it pretty well.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Jane, thank you so much.

JANE MAYER: Glad to be with you.

BOB GARFIELD: Jane Mayer is a staff writer at The New Yorker and author of Dark Money.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, how do you craft a message about climate change, for conservative skeptics?

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media.