BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

Before President Trump insisted on death for the truck driver accused of killing eight people in lower Manhattan on Halloween, he first mused about sending the suspect to Guantánamo Bay.

[CLIP]:

MALE REPORTER: Are you considering that now, Sir?

President Trump: I would, I would certainly consider that. Send him to Gitmo. I would certainly consider that, yes.

[END CLIP]

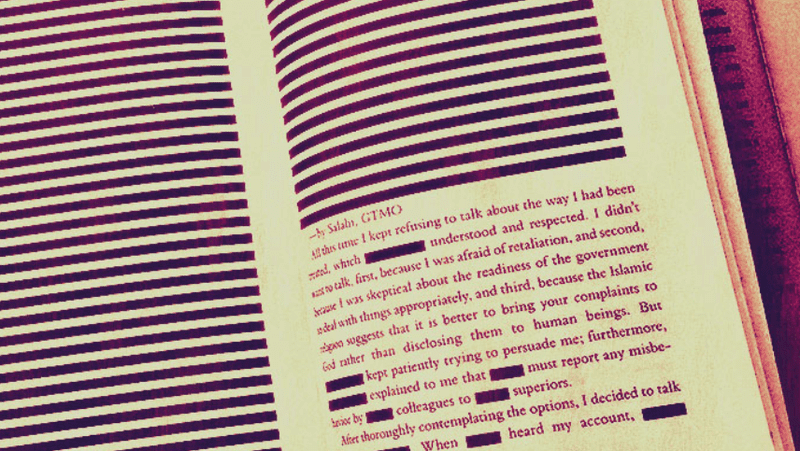

BOB GARFIELD: In 2015, the world got a peek inside, with the publication of Guantanamo Diary, the heavily redacted account of interrogation, imprisonment and torture, written by inmate Mohamedou Ould Slahi. A 29-year-old Mauritanian engineer, Slahi was first detained in 2000 for his supposed connections to the Millennium bomb plot. Though quickly cleared in that matter, he was, nonetheless, kept in custody at the prison for 14 years. Writer and human rights activist Larry Siems edited the book Mohamedou wrote while imprisoned. A year later, Slahi was finally released and he and Siems spent months unredacting the manuscript. Larry, welcome back to the show.

LARRY SIEMS: Thank you, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: Slahi was originally suspected of a connection to the so-called “Millennium bomb plot” to blow up LAX Airport. How so?

LARRY SIEMS: He briefly moved to Canada in 1999, got there just about the time that this guy named Ahmed Ressam was caught coming into the United States with a trunkload of explosives to try to blow up LAX Airport, And because they had gone to the same mosque, Mohamedou fell under suspicion. He actually was living and working peacefully in Mauritania through 9/11. After 9/11, the United States picked up Mohamedou and then on November 20th, 2001 put him on a rendition plan to Jordan, and that began his ordeal in US custody.

BOB GARFIELD: Fourteen years in Guantánamo, with neither evidence nor even a theory of connection to terrorism or anything else untoward.

LARRY SIEMS: He wasn't just mistreated in Guantánamo, he was one of the two most tortured people in Guantánamo, torture that included extreme isolation, deprivations, humiliations, sexual harassment, a fake kidnapping and death threats to his family. That happened between 2003 and 2004. By the end of that time, of course, they had decided that he wasn't who they thought he was, and they kept him in this isolation hut that they had dragged him into for this interrogation that was completely sealed off from the camp. But they began to give him, you know, writing supplies, and he had a new guard team come, come in that was much friendlier to him.

What he did during that time was remarkable. He sat down at this desk that he had in his cell and, over the period of about eight months, wrote in a series of segments that he sort of framed as letters to his lawyers so that they could be transferred to them safely and not destroyed, this manuscript for Guantanamo Diary, which was which was 466 pages handwritten in English, his fourth language.

BOB GARFIELD: And you edited this into book form and it was published but heavily redacted by the government. How heavily?

LARRY SIEMS: Well, there were about 2,400 black bars that had been imposed on the text. You know, his lawyers fought in sort of secret litigation that was connected to his habeas corpus case to get the manuscript declassified. Finally, in 2012, they called me and said, we have this declassified version of the book, handed it to me. It was a PDF file of this handwritten manuscript with these 2,400 redactions that vary from pronoun length all the way up to multi-page redactions. My job was to navigate the challenge of the censorship.

BOB GARFIELD: Okay, that was then, this is now. You have unredacted the redactions. How were you able to reassemble his narrative?

LARRY SIEMS: I got the word that he was being released a year ago and I got a phone call in from a Al Jazeera reporter, you know, who said he was going to the airport to meet Mohamedou. There had been no warning. He had been cleared for release earlier in the summer but, you know, this is the waning days of the Obama administration. Nobody knew whether he’d get out or not. And there he was, apparently, landed in Mauritania. And two hours later, I was driving and my phone rang, and it was Mohamadou, and he was exactly the voice that I knew from the book. He was relaxed. He said, hey, Larry, how are you doing? Two weeks later, I went to Mauritania and visited him.

One of the very first things he said was he really thought he owed his readers the whole story, is it possible to do an unredacted version? Now, the easiest way to do that, of course, would be to get the original manuscript back from the US government. But that was not gonna happen. That will probably never be publicly released. Of course, Mohamedou knows the information that's under those redactions.

BOB GARFIELD: That doesn't strike me as being an easy process. How were you able to reassemble his narrative?

LARRY SIEMS: We sort of went from short to long, so, you know, the short reductions he could just go through and he’d pencil them in. This is so-and-so, he knows who that is. But when you have a seven-page redaction that describes a polygraph exam, you know, how are we going to reconstruct that?

We were asking each other a lot of interesting ethical questions about memory. His commitment all along is to be quite straightforward, so when he couldn't remember something he was very honest with me. There were moments where he would say, I need some time with this one, I hadn't thought about this. You could see him remembering things.

BOB GARFIELD: What is there about the unredacted version of Guantanamo Diary that advances the story for the audience?

LARRY SIEMS: If you look at a redacted manuscript, your first question should be, who's hiding what from whom? If there's one thing that all of these years of looking at censored documents about Guantánamo has taught me, it’s that those reductions exist primarily to keep information from us, the American people. The process of the last 15 years, since the beginning of the torture program, has really been of trying to tear down these walls of censorship that had been built specifically to screen from the American people the crimes that have been done. To this day, no writer or journalist has ever been able to speak with a prisoner while they're in Guantánamo. I could have no communication with Mohamedou while I was working with the original manuscript and he was still in prison. The American public should be asking the question, well, wait, what am I not being allowed to see here?

BOB GARFIELD: Slavery is over but it isn’t over. It continues to reside in history and in the collective consciousness. The trail of tears, over but not over, Tuskegee, over but not over, McCarthyism, all of these horrific chapters of American history. And Guantánamo, which seems to belong in that conversation of our darkest moments, seems to me already to be fading from the public consciousness.

BOB GARFIELD: It does seem to me that we have a unique cultural challenge when it comes to accountability. I think it's partly because we’re a country that was founded on this notion of looking forward, not backwards. But we have compiled and accumulated many, many layers of secrets and crimes over the years that we’ve not fully addressed and we've not learned how important the process of addressing them is for us as individuals and as a culture. So I am worried about Guantánamo. Forty-one men are still incarcerated there. Thousands of American men and women are working there. And, like you say, most of the country is not even thinking about it. We should do better in confronting our mistakes because it'll make us stronger. These crimes are damaging to our character and to our soul. The process of illuminating this darkness is one of repairing something in ourselves.

BOB GARFIELD: Larry, thank you.

LARRY SIEMS: You’re welcome.

BOB GARFIELD: Larry Siems is a writer and human rights activist and editor of the Guantanamo Diary.