BOB GARFIELD: Hubbs is author of Rednecks, Queers and Country Music, and she says that generic assumptions about country betray an underlying discomfort with and misunderstanding of the working class in America.

NADINE HUBBS: It really takes the working class seriously in a way that no other major culture form in America does. The songs, the lyrics about normal people's concerns and joys and sorrows, whatever comes up in ordinary life very often comes up in a country song. So a kid spilling his orange drink in his car seat [LAUGHS] all over the upholstery, that comes up in a country song.

[CLIP/’WATCHING YOU”]

RODNEY ATKINS SINGING:

A green traffic light turned straight to red

I hit my brakes and mumbled under my breath

As fries went a flyin’ and his orange drink covered his lap

NADINE HUBBS: There are all kinds of really banal topics that may come up in country songs because, indeed, they do represent everyday life of people who would call themselves “normal folks.” What has been happening over the past several decades is that there is an ever-wider chasm between the upper middle class and the working class, and that plays out geographically, where folks get educated, who they hang out. We don’t rub elbows anymore and we may not rub elbows with working-class music. Whatever its actual contours are, we keep our distance.

BOB GARFIELD: You never do have to look far for a country music song that plays directly to the stereotype. Just before the Iraq War in 2002, Toby Keith, "Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue.”

[CLIP/TOBY KEITH SINGING]:

And you'll be sorry that you messed with

The U.S. of A.

'Cause we'll put a boot in your ass

It's the American way

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

NADINE HUBBS: Country is often read as even jingoistic. I think that that has to be read not as a political position but rather a familial gesture, given that one study showed that about 80% of US military casualties in Afghanistan were working class. It’s more about country music's constituency actually knowing people who were in the military, unlike many of us. The Toby Keith song started life as a song that he wrote and performed on his USO tours. The troops loved the song and kept asking him, why don’t you record this song? And then he did, perhaps ill- advisedly. [LAUGHS]

Understood in the context of a bunch of 18- and 20-year-olds who are about to be sent into harm’s way, it's very different from the context in which I may hear that song come over the radio in my car.

BOB GARFIELD: What else in this vast genre is not so easily dismissed by people with a different worldview? What has it to offer that tells us more about its audience than people like me understand?

NADINE HUBBS: I could give two examples. One would be the hillbilly humanism that features in country songs, one after another for 70 years, and another more challenging theme is the antibourgeois theme that features in a lot of country songs, too. So hillbilly humanism is what really many country songs boil down to, and it's a very simple message: Nobody's better than anyone else. Hank Williams, Sr. is one of the earliest sources of hillbilly humanism, so a song like "Pictures from Life's Other Side.”

[CLIP/HANK WILLIAMS, SR. SINGING]:

… from life's other side someone has fell by the way

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

NADINE HUBBS: Even like I’ve got “Friends in Low Places” --

[CLIP/GARTH BROOKS SINGING]:

'Cause I've got friends in low places

Where the whiskey drowns

And the beer chases my blues away

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

NADINE HUBBS: -- a Garth Brooks song. It’s about him being pissed off with an ex-girlfriend, it seems, and now she’s marrying a fancy guy and he thinks about how he, [LAUGHS] he went over and threw a wrench into the fancy wedding and then went back over to the bar and joined his friends and spent the rest of the night drinking and having fun. That song has, I would say, both a hillbilly humanism theme in it. It also has the antibourgeois theme in it, that is thumbing the nose at those who look down on, on us. Sometimes they're funny, sometimes they're really angry. Those are the kinds of songs that when a non-country fan would happen to hear one of the songs, they might be really offended, confirming their negative stereotypes. One of those songs is “Redneck Woman,” a very big hit by Gretchen Wilson in 2004.

[CLIP/GRETCHEN WILSON SINGING]:

Some people look down on me

But I don't give a rip

I stand barefooted in my own front yard with a baby on my hip

'Cause I'm redneck woman

I ain't no high class broad

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

NADINE HUBBS: She’s talking about how, yeah, her lingerie doesn’t come from Victoria's Secret, it comes from Walmart, but she’s still sexy. It’s really clever, and the entire song is just about telling off the people who look down on her and people like her.

One of the things that we could hear in country music, if we listened, is that, while we’re often in denial that we have class differences, country songs every day are showing us otherwise. I mean, you know a song from the ‘70s like “Take This Job and Shove It.”

[CLIP/JOHNNY PAYCHECK SINGING]:

Take this job and shove it

I ain't working here no more

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

NADINE HUBBS: He’s having a fantasy about telling off his supervisor who’s a superior, kind of a middle-class person.

BOB GARFIELD: I’m glad you brought up “Take This Job and Shove It” because the author of that song, an outlaw country artist named David Allan Coe, wrote another song, which we can't play much of here. [LAUGHS] Tell me about that song, [CHUCKLES] to, to the extent that you can on public radio, and explain why it's actually significant.

NADINE HUBBS: Well, I think you're talking about David Allan Coe’s 1978 underground track, “F—Aneta Briant.”

[CLIP ]:

F-Anita Bryant

Who the Hell is she

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

NADINE HUBBS: Anita Bryant was a 1958 runner-up in the Miss America Pageant. She was a middle-of-the-road singer who had some Top 40 hits, and then she became the spokeswoman for the Florida Citrus Growers Association in the ‘70s. As a resident of Miami-Dade, she opposed a local ordinance that would have extended some equal rights protection to what we would now call LGBTQ citizens. Only months after she first spearheaded that campaign, David Allan Coe, of all people, this outlaw country star, wrote a song, “F—Aneta Briant.” It was certainly nothing that was playable on country radio or any other kind of radio. And in the song, he makes it clear that he's [LAUGHS] very familiar not only with men who had sex with men in prison, he implies pretty strongly that he's familiar with it in every way and that, actually, those people she calls homosexuals are a lot more diverse than she imagines. [LAUGHS] In his lyrics, he goes through a whole list. Some are yellow bellied, that some are mean.

[CLIP/DAVID ALLAN COE SINGING]:

Some are killers

Some are thieves

And some are singers too

In fact, Anita Bryant

Some act just like you

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

NADINE HUBBS: The problems of a lot of our assumptions about who has been the hero and savior of liberal causes, such as LGBTQ rights, for the first 100 years of homosexuality, from around 1870, when that label was devised, to about the 1970s, the sin of the working class was not that they were queer haters but that they were queer lovers. It’s only been since the civil rights era when tolerance rose in importance, then the middle class became the owners of queer acceptance and the working-class sin was suddenly that they were queer haters.

BOB GARFIELD: Maybe, at this point, we should also discuss a song from Merle Haggard, the very person who turned “Okie from Muskogee” into a sort of anthem, actually --

NADINE HUBBS: Uh huh.

BOB GARFIELD: -- in defense of -- interracial marriage.

NADINE HUBBS: He released “Okie from Muskogee” in 1969. It catapulted him into a level of stardom that he had not known before. He gained lots of new fans who were suburban conservatives. His fan base had previously overlapped with Dylan's fan base, you know, songs about social justice, songs about the downtrodden. After Haggard had such an enormous hit, his record company asked him, okay, what's gonna be your follow-up? And back then, in any pop musical category, if you had a big hit, you would try to strike while the iron is hot and launch another song. Often it would sound the same. It might have, more or less, the same chord changes or the same groove. Merle Haggard's answer was he wanted to release “Irma Jackson.”

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

It was the antithesis of “Okie from Muskogee.” The narrator sings to a woman he has loved since childhood and who he will love “’til I die” who is forbidden to him because she's black.

[CLIP/MERLE HAGGARD SINGING]:

There's no way the world will understand that love is color blind

That's why Irma Jackson can't be mine

NADINE HUBBS: The record company said, no, Merle, we want another song that’s gonna appeal to the same people who are lovin’ “Okie.” And the song that he did release was another song that appealed to those who didn't like hippies and didn't like Vietnam War protesters. It was called “The Fightin’ Side of Me.”

BOB GARFIELD: If our goal is to really understand not just country music as a genre but its audience and a wide swath of America, what do we do?

NADINE HUBBS: The problem is confirmation bias. If you already hate the sound of country music and country music is something you’ve learned to associate with this group of people who you think of as -- the phrase I coin in my book, “the bigot class,” the racist people, the homophobic people, the sexist people -- it's a nice fantasy that takes the middle class, upper middle class off the hook, despite the fact that they actually have their hands on the levers of institutional power that could really make changes in society. To blame America's social ills on some of its least influential citizens is distortive wishful thinking. So how do we stop or slow down a stereotype? I'd be happy to share a playlist [LAUGHS] that could give you a broader picture of country music fans but the problem would be maybe you would wince at [LAUGHS] every song.

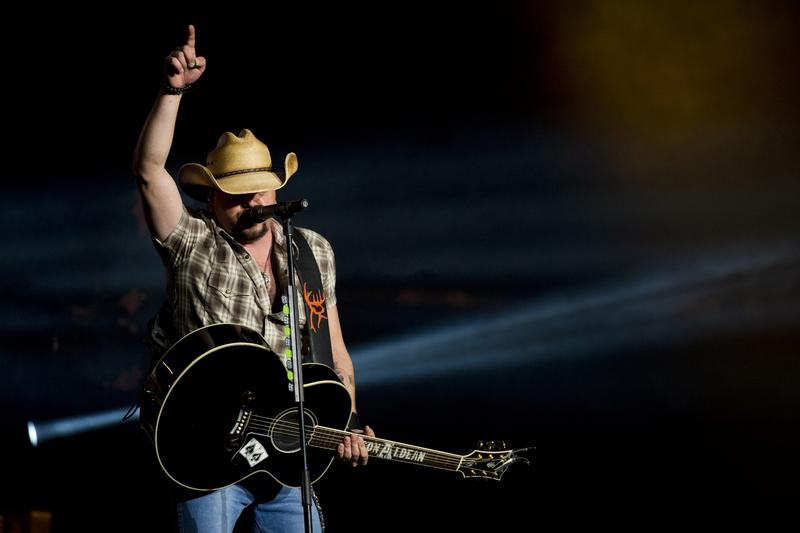

BOB GARFIELD: You know, one of the sad ironies of this conversation is that there is a song that is about exactly what we’re discussing. It’s called “They Don’t Know” and it's by Jason Aldean --

NADINE HUBBS: Uh huh.

BOB GARFIELD: -- who was the artist performing --

NADINE HUBBS: Yeah.

BOB GARFIELD: --- in Las Vegas when the shots rang out.

[CLIP/JASON ALDEAN SINGING]:

But those folks ain’t lived in our lives

They ain’t seen the blood, sweat and tears it took to live their dreams

When everything’s on the line

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

NADINE HUBBS: Nowadays, in country music, this theme comes up again and again. It comes up with melancholy. It comes up with rage. Being judged, being misunderstood, “they don't know.”

BOB GARFIELD: Nadine, thank you very much

NADINE HUBBS: Thank you, Bob. It's been a pleasure.

BOB GARFIELD: Nadine Hubbs is a professor of women’s studies and music at the University of Michigan and author of “Rednecks, Queers and Country Music.”

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, the new Blade Runner. Like the original it examines the slippery concept of memory.

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media.