9/11 Enters the Realm of Museum

( Meara Sharma

)

Transcript

BOB GARFIELD: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. If journalism is the first draft of history, “museumification” probably is the last. So, OTM producer Meara Sharma and I went down to mark that moment for 9/11, on the opening day of the museum in its name, built on the footprint of the twin towers.

[SOUND OF WATER/VOICES]

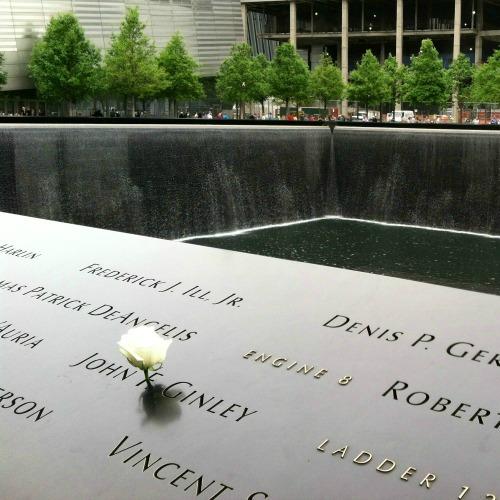

You’re hearing one of two huge fountains, each one roughly the size of a tower. The water flows down from long straight walls, across a black square, into a smaller square with no visible bottom. Surrounding the fountain is a black granite flat form where the names of the dead are inscribed, arranged not alphabetically or chronologically, but in accordance with something called “meaningful adjacency.” Essentially, the friendships and personal relationships were mapped and then an algorithm linked together the names. It means that someone who helped a stranger, but they both died, will be next to each other on the wall. Inside, you first encounter the sight and sound of those who saw 9/11 from afar, an estimated one-third of humanity.

[VOICES IN BACKGROUND OF THOSE WHO SAW FROM AFAR]

WOMAN: September 11th, 2001.

WOMAN: I'll never forget where I was.

MAN: I was in a coffee shop in Knoxville, Tennessee.

WOMAN: I was watching my grandchild.

WOMAN: I was driving to work at 5:45 local time -

MAN: The first thing I thought of was my parents. I wanted to talk to the people that I loved the most

MAN: So I started to call all my friends.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I go to the end of the hall, the broad swath of the blue tiles. And in the midst of those tiles is the saying in raised stone, a quote from Virgil, “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.”

CHILD: My Dad, Michael, Joseph-

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Then people reciting the names of those they personally lost.

[VOICES SAYING THOSE THEY LOST]

[VOICES UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There are walls of glossy 8 x 10s of the dead, and a database.

QUESTION: Is there something helpful about looking up your cousin on this database?

PATTY ANN: Well, I just told my cousin’s wife that we were coming here, so I told her that I would see if I could find anything. And I just happened to walk in and the picture was right there.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Is it strange that someone you know is going to be enshrined in a museum for as long as this museum exists?

PATTY ANN: Yeah. It brings it more to home, probably, you know.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: More to home?

PATTY ANN: Well, ‘cause I, I grew up in Yonkers. You know, we could see the smoke down the Metro North train station after, so that was home. And I had a lot of cousins that worked down here, and they – you know, they did survive, but knowing that my cousin’s cousin didn’t, you know, it’s hard.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I just wonder how weird it must be to have living history.

PATTY ANN: When you are living. Yeah, no, it’s true. Everything we’re seeing here, you know, I saw it live on TV, you know, so it’s, it’s, it’s – it’s strange.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you think you’ll come back?

PATTY ANN: I might, yeah. I might, you know, come back with other family members or what-not, but yes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So it’s working for you.

PATTY ANN: Yeah, they did a good job, and it came out – it’s beautiful, I think.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you so much.

PATTY ANN: You’re welcome.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Can I ask your name?

PATTY ANN: Patty Ann.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thanks.

PATTY ANN: You’re welcome.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You don’t want to, on this first day of this museum, approach people who’ve experienced devastating loss. On the other hand, of course, I do. I’m a radio reporter.

This wall of pictures was created with resources contributed by family members and friends of those killed in the attack. Wow, wedding pictures, Jill Marie Campbell, looks beautiful. Charles R. Mendez, the fireman. He looks really young. Patricia Ann Cimaroli Massari is wearing a tiara. She looks like she won a beauty pageant.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Across the hall, there’s a balcony and down the stairs the concrete stuff of toppled temples and soaring blades of twisted metal. Meara, this is the most stunning piece of bent metal that I’ve ever laid eyes on.

MEARA SHARMA: Almost like arms reaching.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

MEARA SHARMA: Limbs kind of twisted.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah.

MEARA SHARMA: It’s incredibly majestic, actually.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It says that it’s the section of the steel façade, North Tower, floors 93 to 96.

MEARA SHARMA: The underbelly of the aircraft actually mangled this section of wall. There’s something so oddly kind of sculptural about everything, curved and bent metal and just the weight of it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This looks like something John Chamberlain might have made. A lot of this stuff does, crushed metal, a confusion of chaos and intention, you know, abstract expressionism, spontaneous and yet designed to evoke feelings in others. This whole event was designed to evoke feelings in others. Does this museum mean that the terrorists lost or won? You know, it’s a stupid question, anyway. I hate that question.

[MUSIC IN BACKGROUND/UP & UNDER]

The World Trade Center, by the numbers: Approximately 50,000 people worked in it. Each tower had 110 floors. Each floor was an acre in size. On windy days, each tower would sway 12 inches side to side. There are 198 elevators in the twin towers and 15 miles of elevator shafts. On a clear day, you could see 45 miles in each direction from the Observation Deck.

[VOICES IN BACKGROUND]

There’s a place where they keep the toughest stuff, not the world’s witnesses nor even the bereaved, but the perspective of those on the ground in the moment.

WOMAN: What we did was we made a little alcove and we made a warning saying that this is what’s in here. If you want to come in, go ahead. We also suggest not to bring kids in here, so it’s, it’s not completely displayed. We, we give warning about it. And it is a little difficult to find, so I’ll just walk you over there as well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you.

WOMAN: Mm-hmm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: We go through a revolving door.

[RECORDINGS]:

MAN: Building One and Building Two. Roger, evacuate all buildings in the complex, you got that, all buildings in the complex.

[TELEPHONE RINGING]

MAN: Fire Department. They’re through – they’re coming through the building, sir. I got almost every fireman in the city coming to help you. I understand. Just, just sit tight. That’s what we got – we’ll get to you as soon as we can.

MEARA SHARMA: It’s a series of assaults, you know, the texts, the images, the audio playing. It’s like being inside this kind of horror vortex or something.

MAN: My first thought was that I’m dead. And then I started to smell smoke. I felt above my head there was a slab of concrete that had fallen at an angle, and at that point I heard someone behind me say, “Don’t leave me.” And he grabbed my ankle, he moved behind me, and I just started digging.

MAN: The next thing I remember was just a bright, bright light and somebody saying, “If you see the light, come to the light.” I’m hearing noises and I’m hearing, “Help me” and it’s just so surreal, like I’m in a dream or something.

WOMAN: I just now started picking people up and saying, “Wait here, I’m gonna step out and look up and when I tell you to go, you need to go like you’ve never gone before.”

MAN: Twenty minutes later I saw a little peephole of light. I was able to make a small hole, and so I said to the man behind me, “I’ll squeeze you through the hole.” I pushed him up and I squeezed myself through the rebar. I scraped my body down completely.We were on a pile of rubble. It was red hot. My shoes began to melt into the gutter as I was standing there. All around me was like being in a blizzard; it was just paper, gray smoke, everything swirling.

WOMAN: As we were going along, you’re like kind of picking up people that are just wandering. People are disoriented because nothing looks the way it did an hour ago. Just the whole area was gray. Even when you looked up, all you saw was gray.

[END RECORDINGS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: CeeCee Lyles was a flight attendant. She leaves a message for her husband.

[RECORDING]:

CEECEE LYLES: Hi baby, I'm – baby, you have to listen to me carefully. I'm on a plane that's been hijacked. I'm on the plane, I'm calling from the plane. I want to tell you I love you. Please tell my children that I love them very much and I'm so sorry they - um, I don't know what to say. There are three guys, they've hijacked the plane. I’m trying to be calm. We're turned around, and I've heard that there's planes that, that – that flown into the World Trade Center. I hope to be able to see your face again, baby. I love you. Bye.

[END RECORDING]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There’s an alcove with photos of those who chose to jump, rather than burn, both at the moment of decision and then plummeting, floating. There’s also quotes from those who watched, like James Gilroy. “She had a business suit on. Her hair was all askew. This woman stood there for what seemed like minutes and then she held down her skirt and just stepped off the ledge. I thought, how human, how modest, to hold down her skirt before she jumped. I couldn't look anymore.”

MAN: Sir we have seven patients and more patients are coming to us, Park Place and West Broadway.

[RECORDINGS CONTINUE/UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Though the visitors certainly were solemn, there were no tears. Maybe after more than a decade of anniversaries, the national mantle of mourning no longer suits the time. After all, the city and the nation have seen many catastrophes. This was a huge one but perhaps more important, it was our catastrophe. Fifty years from now, it will be a catastrophe. And it’s in places like these that future generations will experience it. What that experience will be like for them, we can’t possibly know.

[SOUNDS OF REVOLVING DOORS]

JAKE BARTON: I’m Jake Barton, principal and founder of Local Projects. We’re the media designer and production firm for the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What was the hardest thing?

JAKE BARTON: The hardest thing about the project was trying to balance between the emotional safety of the visitors, a young adult, a 15-year-old who knows literally nothing about this day, and, on the other side, first responders or people that ran out of the burning buildings for their lives. And so, trying to make an authentic and, frankly, meaningful experience for both audiences was an incredible challenge.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: When you walk in, you hear this montage of voices, people who experienced it from a distance, but when you go through the revolving doors you are then put in the path of the direct experience of the people on the site at that moment.

JAKE BARTON: We gathered voices from all around the world, through the internet, through phone, through a story booth that we have here on site, and it brings us back onto our own memories.When you go into the historic exhibition, you are literally placed into the moment, and it frankly is a moment of confusion and of revelation. You hear some people repeating misinformation, claiming on the news that this is just a small Cessna plane; it’s clearly an accident. We actually place people inside of that moment of revelation, to remind people that at that moment 9/11 was impossible, until it happened.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The museum's role is to create an experience for a generation that has no contact with it, like the Lincoln Memorial.

JAKE BARTON: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How do you go about imagining how that might be experienced in 50 years?

JAKE BARTON: I think the – both the memorial and certainly the museum have a very interesting relationship with time; 9/11, it's not history, right, because it's still unfolding and its effects are literally being played out in headlines today, whether it’s about Guantanamo, the Middle East, personal security and freedoms, all of these ways in which the post-9/11 world is continuing to evolve and change. And yet, it’s definitely not current events. It’s somewhere in between. And so, the museum’s job, I think, is both to preserve the memories, to tell the full story but, frankly, to do what it can to play a productive role within all of the conversations that are literally defining this post-9/11 world.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The whole of history doesn't tell us about what was going on in Afghanistan in the eighties and doesn't talk about America's role in, frequently over the decades, supporting unpopular leaders in the region and generating hostility, thereby.

JAKE BARTON: So it’s a big museum, there’s a lot in it. There’s, actually really strong overt references to the history of the Middle East, to the rise of the radical fringe that led to al Qaeda, including America's role within the Middle East, and certainly within the –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It is? I’m, I’m just appalled that I seem to have strode right by that section. There are certain things that you really can't avoid passing through.

JAKE BARTON: No question.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You know, this sort of historical part, I guess it was a decision not to make it an obligatory walkthrough.

JAKE BARTON: Yes, definitely, definitely. We opted for a museum experience where there are different levels of disclosure, and so, we don't necessarily have a, a children's exhibit but we do have a general interstitial space, which is actually the majority of the museum, that is really absent of the toughest parts of the story. It has a crushed fire truck and it has pictures of the towers there and gone, it has missing posters, it has the last column. But you have to actually enter through those revolving doors into the historic exhibition to get the story of the day and the day before and the aftermath. And then even within there, there are different alcoves that tell even tougher parts of the stories, from inside the towers and from inside of Flight 93. It’s essentially allowing people to, again, make the choice to go in and to be confronted with the most difficult material inside the museum.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So much of this – I mean, I am a big art museum goer.

JAKE BARTON: Sure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I would see a Chamberlain sculpture-

JAKE BARTON: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - and, and a Richard Serra structure and things that look like religious iconography.

JAKE BARTON: Yep.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Did any of that strike you? I mean –

JAKE BARTON: Yeah, there was a ton of conversation during the planning and design process about how to distinctly actually avoid aestheticizing different parts of this experience, because the artifacts themselves are so powerful it’s just not appropriate to try and put something on top of them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Our natural tendency to anthropomorphize makes you see arms reaching up to heaven or –

JAKE BARTON: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - twisted limbs. There’s a lot of pain that’s evoked by those inanimate objects, even if we saw them entirely absent at 9/11, as a context.

JAKE BARTON: No question. I think the context though, because you're inside of essentially the largest artifacts, the void that the museum fills, the original infrastructure that held the towers, and you’re on the site, this hallowed ground, it charges the atmosphere in the mind, so that when see the fire truck that we have inside the historic exhibition, one part of it that you encounter is completely pristine; it’s almost untouched. And then when you turn a corner, you see the front, which is completely charred, completely destroyed. We couldn’t help but notice that’s essentially a metaphor for the day.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

You turned left, you lived. You turned right, you perished. And that was simply the fact of that day, just based on how the towers went down and on the lives that were lost

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Jake Barton, of Local Projects, the media designer and production firm for the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A word about that controversial gift shop, it had lots of books ranging from collections of photos, to personal recollections, to the 9/11 report, to histories like The Looming Tower. There was an NYPD jacket for your dog. In fact, there were a lot of tributes to search and rescue dogs. There were "I Love New York More Than Ever" mugs. Images of that survivor tree found living in the rubble on mugs and t-shirts. There was a sweatshirt with the saying "In darkness, we shine the brightest." Seems a delicate notion for a hoodie, but we were offended by none of it. The reality is, 9/11 was commodified long ago. Now it lives in a museum, and people may want a little something to remember it by.

BOB GARFIELD: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. If journalism is the first draft of history, “museumification” probably is the last. So, OTM producer Meara Sharma and I went down to mark that moment for 9/11, on the opening day of the museum in its name, built on the footprint of the twin towers.

[SOUND OF WATER/VOICES]

You’re hearing one of two huge fountains, each one roughly the size of a tower. The water flows down from long straight walls, across a black square, into a smaller square with no visible bottom. Surrounding the fountain is a black granite flat form where the names of the dead are inscribed, arranged not alphabetically or chronologically, but in accordance with something called “meaningful adjacency.” Essentially, the friendships and personal relationships were mapped and then an algorithm linked together the names. It means that someone who helped a stranger, but they both died, will be next to each other on the wall. Inside, you first encounter the sight and sound of those who saw 9/11 from afar, an estimated one-third of humanity.

[VOICES IN BACKGROUND OF THOSE WHO SAW FROM AFAR]

WOMAN: September 11th, 2001.

WOMAN: I'll never forget where I was.

MAN: I was in a coffee shop in Knoxville, Tennessee.

WOMAN: I was watching my grandchild.

WOMAN: I was driving to work at 5:45 local time -

MAN: The first thing I thought of was my parents. I wanted to talk to the people that I loved the most

MAN: So I started to call all my friends.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I go to the end of the hall, the broad swath of the blue tiles. And in the midst of those tiles is the saying in raised stone, a quote from Virgil, “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.”

CHILD: My Dad, Michael, Joseph-

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Then people reciting the names of those they personally lost.

[VOICES SAYING THOSE THEY LOST]

[VOICES UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There are walls of glossy 8 x 10s of the dead, and a database.

QUESTION: Is there something helpful about looking up your cousin on this database?

PATTY ANN: Well, I just told my cousin’s wife that we were coming here, so I told her that I would see if I could find anything. And I just happened to walk in and the picture was right there.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Is it strange that someone you know is going to be enshrined in a museum for as long as this museum exists?

PATTY ANN: Yeah. It brings it more to home, probably, you know.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: More to home?

PATTY ANN: Well, ‘cause I, I grew up in Yonkers. You know, we could see the smoke down the Metro North train station after, so that was home. And I had a lot of cousins that worked down here, and they – you know, they did survive, but knowing that my cousin’s cousin didn’t, you know, it’s hard.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I just wonder how weird it must be to have living history.

PATTY ANN: When you are living. Yeah, no, it’s true. Everything we’re seeing here, you know, I saw it live on TV, you know, so it’s, it’s, it’s – it’s strange.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you think you’ll come back?

PATTY ANN: I might, yeah. I might, you know, come back with other family members or what-not, but yes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So it’s working for you.

PATTY ANN: Yeah, they did a good job, and it came out – it’s beautiful, I think.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you so much.

PATTY ANN: You’re welcome.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Can I ask your name?

PATTY ANN: Patty Ann.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thanks.

PATTY ANN: You’re welcome.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You don’t want to, on this first day of this museum, approach people who’ve experienced devastating loss. On the other hand, of course, I do. I’m a radio reporter.

This wall of pictures was created with resources contributed by family members and friends of those killed in the attack. Wow, wedding pictures, Jill Marie Campbell, looks beautiful. Charles R. Mendez, the fireman. He looks really young. Patricia Ann Cimaroli Massari is wearing a tiara. She looks like she won a beauty pageant.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Across the hall, there’s a balcony and down the stairs the concrete stuff of toppled temples and soaring blades of twisted metal. Meara, this is the most stunning piece of bent metal that I’ve ever laid eyes on.

MEARA SHARMA: Almost like arms reaching.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

MEARA SHARMA: Limbs kind of twisted.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah.

MEARA SHARMA: It’s incredibly majestic, actually.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It says that it’s the section of the steel façade, North Tower, floors 93 to 96.

MEARA SHARMA: The underbelly of the aircraft actually mangled this section of wall. There’s something so oddly kind of sculptural about everything, curved and bent metal and just the weight of it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This looks like something John Chamberlain might have made. A lot of this stuff does, crushed metal, a confusion of chaos and intention, you know, abstract expressionism, spontaneous and yet designed to evoke feelings in others. This whole event was designed to evoke feelings in others. Does this museum mean that the terrorists lost or won? You know, it’s a stupid question, anyway. I hate that question.

[MUSIC IN BACKGROUND/UP & UNDER]

The World Trade Center, by the numbers: Approximately 50,000 people worked in it. Each tower had 110 floors. Each floor was an acre in size. On windy days, each tower would sway 12 inches side to side. There are 198 elevators in the twin towers and 15 miles of elevator shafts. On a clear day, you could see 45 miles in each direction from the Observation Deck.

[VOICES IN BACKGROUND]

There’s a place where they keep the toughest stuff, not the world’s witnesses nor even the bereaved, but the perspective of those on the ground in the moment.

WOMAN: What we did was we made a little alcove and we made a warning saying that this is what’s in here. If you want to come in, go ahead. We also suggest not to bring kids in here, so it’s, it’s not completely displayed. We, we give warning about it. And it is a little difficult to find, so I’ll just walk you over there as well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you.

WOMAN: Mm-hmm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: We go through a revolving door.

[RECORDINGS]:

MAN: Building One and Building Two. Roger, evacuate all buildings in the complex, you got that, all buildings in the complex.

[TELEPHONE RINGING]

MAN: Fire Department. They’re through – they’re coming through the building, sir. I got almost every fireman in the city coming to help you. I understand. Just, just sit tight. That’s what we got – we’ll get to you as soon as we can.

MEARA SHARMA: It’s a series of assaults, you know, the texts, the images, the audio playing. It’s like being inside this kind of horror vortex or something.

MAN: My first thought was that I’m dead. And then I started to smell smoke. I felt above my head there was a slab of concrete that had fallen at an angle, and at that point I heard someone behind me say, “Don’t leave me.” And he grabbed my ankle, he moved behind me, and I just started digging.

MAN: The next thing I remember was just a bright, bright light and somebody saying, “If you see the light, come to the light.” I’m hearing noises and I’m hearing, “Help me” and it’s just so surreal, like I’m in a dream or something.

WOMAN: I just now started picking people up and saying, “Wait here, I’m gonna step out and look up and when I tell you to go, you need to go like you’ve never gone before.”

MAN: Twenty minutes later I saw a little peephole of light. I was able to make a small hole, and so I said to the man behind me, “I’ll squeeze you through the hole.” I pushed him up and I squeezed myself through the rebar. I scraped my body down completely.We were on a pile of rubble. It was red hot. My shoes began to melt into the gutter as I was standing there. All around me was like being in a blizzard; it was just paper, gray smoke, everything swirling.

WOMAN: As we were going along, you’re like kind of picking up people that are just wandering. People are disoriented because nothing looks the way it did an hour ago. Just the whole area was gray. Even when you looked up, all you saw was gray.

[END RECORDINGS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: CeeCee Lyles was a flight attendant. She leaves a message for her husband.

[RECORDING]:

CEECEE LYLES: Hi baby, I'm – baby, you have to listen to me carefully. I'm on a plane that's been hijacked. I'm on the plane, I'm calling from the plane. I want to tell you I love you. Please tell my children that I love them very much and I'm so sorry they - um, I don't know what to say. There are three guys, they've hijacked the plane. I’m trying to be calm. We're turned around, and I've heard that there's planes that, that – that flown into the World Trade Center. I hope to be able to see your face again, baby. I love you. Bye.

[END RECORDING]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There’s an alcove with photos of those who chose to jump, rather than burn, both at the moment of decision and then plummeting, floating. There’s also quotes from those who watched, like James Gilroy. “She had a business suit on. Her hair was all askew. This woman stood there for what seemed like minutes and then she held down her skirt and just stepped off the ledge. I thought, how human, how modest, to hold down her skirt before she jumped. I couldn't look anymore.”

MAN: Sir we have seven patients and more patients are coming to us, Park Place and West Broadway.

[RECORDINGS CONTINUE/UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Though the visitors certainly were solemn, there were no tears. Maybe after more than a decade of anniversaries, the national mantle of mourning no longer suits the time. After all, the city and the nation have seen many catastrophes. This was a huge one but perhaps more important, it was our catastrophe. Fifty years from now, it will be a catastrophe. And it’s in places like these that future generations will experience it. What that experience will be like for them, we can’t possibly know.

[SOUNDS OF REVOLVING DOORS]

JAKE BARTON: I’m Jake Barton, principal and founder of Local Projects. We’re the media designer and production firm for the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What was the hardest thing?

JAKE BARTON: The hardest thing about the project was trying to balance between the emotional safety of the visitors, a young adult, a 15-year-old who knows literally nothing about this day, and, on the other side, first responders or people that ran out of the burning buildings for their lives. And so, trying to make an authentic and, frankly, meaningful experience for both audiences was an incredible challenge.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: When you walk in, you hear this montage of voices, people who experienced it from a distance, but when you go through the revolving doors you are then put in the path of the direct experience of the people on the site at that moment.

JAKE BARTON: We gathered voices from all around the world, through the internet, through phone, through a story booth that we have here on site, and it brings us back onto our own memories.When you go into the historic exhibition, you are literally placed into the moment, and it frankly is a moment of confusion and of revelation. You hear some people repeating misinformation, claiming on the news that this is just a small Cessna plane; it’s clearly an accident. We actually place people inside of that moment of revelation, to remind people that at that moment 9/11 was impossible, until it happened.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The museum's role is to create an experience for a generation that has no contact with it, like the Lincoln Memorial.

JAKE BARTON: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How do you go about imagining how that might be experienced in 50 years?

JAKE BARTON: I think the – both the memorial and certainly the museum have a very interesting relationship with time; 9/11, it's not history, right, because it's still unfolding and its effects are literally being played out in headlines today, whether it’s about Guantanamo, the Middle East, personal security and freedoms, all of these ways in which the post-9/11 world is continuing to evolve and change. And yet, it’s definitely not current events. It’s somewhere in between. And so, the museum’s job, I think, is both to preserve the memories, to tell the full story but, frankly, to do what it can to play a productive role within all of the conversations that are literally defining this post-9/11 world.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The whole of history doesn't tell us about what was going on in Afghanistan in the eighties and doesn't talk about America's role in, frequently over the decades, supporting unpopular leaders in the region and generating hostility, thereby.

JAKE BARTON: So it’s a big museum, there’s a lot in it. There’s, actually really strong overt references to the history of the Middle East, to the rise of the radical fringe that led to al Qaeda, including America's role within the Middle East, and certainly within the –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It is? I’m, I’m just appalled that I seem to have strode right by that section. There are certain things that you really can't avoid passing through.

JAKE BARTON: No question.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You know, this sort of historical part, I guess it was a decision not to make it an obligatory walkthrough.

JAKE BARTON: Yes, definitely, definitely. We opted for a museum experience where there are different levels of disclosure, and so, we don't necessarily have a, a children's exhibit but we do have a general interstitial space, which is actually the majority of the museum, that is really absent of the toughest parts of the story. It has a crushed fire truck and it has pictures of the towers there and gone, it has missing posters, it has the last column. But you have to actually enter through those revolving doors into the historic exhibition to get the story of the day and the day before and the aftermath. And then even within there, there are different alcoves that tell even tougher parts of the stories, from inside the towers and from inside of Flight 93. It’s essentially allowing people to, again, make the choice to go in and to be confronted with the most difficult material inside the museum.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So much of this – I mean, I am a big art museum goer.

JAKE BARTON: Sure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I would see a Chamberlain sculpture-

JAKE BARTON: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - and, and a Richard Serra structure and things that look like religious iconography.

JAKE BARTON: Yep.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Did any of that strike you? I mean –

JAKE BARTON: Yeah, there was a ton of conversation during the planning and design process about how to distinctly actually avoid aestheticizing different parts of this experience, because the artifacts themselves are so powerful it’s just not appropriate to try and put something on top of them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Our natural tendency to anthropomorphize makes you see arms reaching up to heaven or –

JAKE BARTON: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - twisted limbs. There’s a lot of pain that’s evoked by those inanimate objects, even if we saw them entirely absent at 9/11, as a context.

JAKE BARTON: No question. I think the context though, because you're inside of essentially the largest artifacts, the void that the museum fills, the original infrastructure that held the towers, and you’re on the site, this hallowed ground, it charges the atmosphere in the mind, so that when see the fire truck that we have inside the historic exhibition, one part of it that you encounter is completely pristine; it’s almost untouched. And then when you turn a corner, you see the front, which is completely charred, completely destroyed. We couldn’t help but notice that’s essentially a metaphor for the day.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

You turned left, you lived. You turned right, you perished. And that was simply the fact of that day, just based on how the towers went down and on the lives that were lost

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Jake Barton, of Local Projects, the media designer and production firm for the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A word about that controversial gift shop, it had lots of books ranging from collections of photos, to personal recollections, to the 9/11 report, to histories like The Looming Tower. There was an NYPD jacket for your dog. In fact, there were a lot of tributes to search and rescue dogs. There were "I Love New York More Than Ever" mugs. Images of that survivor tree found living in the rubble on mugs and t-shirts. There was a sweatshirt with the saying "In darkness, we shine the brightest." Seems a delicate notion for a hoodie, but we were offended by none of it. The reality is, 9/11 was commodified long ago. Now it lives in a museum, and people may want a little something to remember it by.

Hosted by Brooke Gladstone

Produced by WNYC Studios