BROOKE GLADSTONE: Effectively depicting the violence and corruption around the war on drugs and the Mexican-U.S. drug trade is no easy task, even for those steeped in its ins and outs. For well over a decade, Charles Bowden has been covering North America’s unofficial capital of drug violence, the Mexico border city, Juarez. Bowden’s latest work, Dreamland: The Way Out of Juarez, takes a hybrid approach to convey the futility and the carnage, using reportage, poetic language, transcripts from police interviews and, woven throughout, medieval-looking illustrations by Texas-based artist Alice Leora Briggs. Taken together, it has the impact of a fever dream. At one point, Bowden writes, “The state persists just as astrology persists and many things persist, but the state has become a shadow on the wall that pretends to be in charge. The order now comes from the streets, and it is unruly but regular, unfair but as certain as a killing frost, and everyone decides this is the way it has always been.” Bowden goes on:

CHARLES BOWDEN: “Something, whiff of hellfire or of heaven. something of the future already arrived in the small condo on the side street in the city that causes fear to the heart, the city that cannot be discussed or examined, the city with dust in the air and men and women in the ground.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That small condo was the scene of many horrific murders, and Bowden says that when the story of the condo broke in early 2004, it was one of the first times the uncontained violence of Juarez was publicly acknowledged. By focusing on this one condo, Bowden tries to tell the story of the whole city, a city, he says, that’s dying.

CHARLES BOWDEN: An estimated 100- to 400,000 people fled it in the last 18 months. Twenty-five percent of the houses have been abandoned, 100,000 jobs have been lost. Forty percent of the businesses have closed. The city is dying. Violence isn't an incident anymore, it’s the actual fabric of life. It’s part of basic transactions there. Last Friday, 15 people were slaughtered in Juarez. This goes on every day. This book is about a house in Juarez. They would take people there, torture them, execute them and then they would bury them in the backyard and pour lime on them so they would decay swiftly. In a four-month period, they put 14 people in that back patio.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Describe what the death house was that you've built so much of your book around.

CHARLES BOWDEN: The death house was a very nice condo in a middleclass neighborhood six blocks from a sushi parlor in a high-end hotel. It was used by the Juarez cartel as a killing ground. These houses are all over the city. The drug organizations always have deals with legitimate government, and part of the deal is not to embarrass the legitimate government. And so, they disappear bodies. This house is simply a tactic to vanish people. In 2008, two more houses came to public notice. One of them had 9 corpses in it, another one had 35. But they're all over the city. I have maps of some of them gotten from cartel members. These people will never be excavated and they will never be acknowledged.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The point here seems to be one of relentless, inevitable injustice.

CHARLES BOWDEN: And corruption. In this case, the executions were done by state policemen who were hired by the drug organization in Juarez to do the killing. This is common. I have interviewed a professional killer, or sicario, who has killed hundreds of people there. But, in fact, he was a commandante in the Mexican state police in Chihuahua, in charge of their anti-kidnapping unit. Part of what you’re seeing on the border is a mutual fantasy or fraud perpetrated by both governments. On the U.S. side and these agencies are slowly being corrupted, and they're being corrupted because the money’s so big. I've interviewed gang leaders in Juarez, and I'd say, how do you move drugs to El Paso? And they'd say, well, we use the Border Patrol and the U.S. Army. I've interviewed cartel members, and I said, don't you ever worry about DEA and the FBI? And they'd say, no, we have people in there. Now, I don't think these stories are false, and certainly nobody in DEA has any trouble believing them. But they are buried. Nobody will talk about them out loud.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But why wouldn't reporters want to tell a story like this?

CHARLES BOWDEN: There’s two hindrances to the U.S. press. One, there can be an element of danger messing around the border. Secondly, it is far easier to take in a statement from an agency or a public official than to go investigate it. They take the easy way out. I mean, I have been baffled for over 20 years why one of the biggest stories in my country is underreported, both the explosion of drug money and the explosion of human beings. Mexico is collapsing. This is an exodus of human beings. This is a far more significant event for the future of the United States than the war in Iraq.

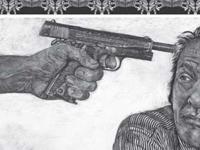

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now explain to me why you chose to take Alice Leora Briggs up on her suggestion that she illuminate this manuscript, almost like a medieval text.

CHARLES BOWDEN: When I agreed to do this with Alice Leora Briggs, I had never met her. She had sent me a, a CD with some of her drawings, and I looked at them, and what I saw instantly was that this person understands pain. I didn't want someone that would illustrate what I wrote, meaning I describe an execution, there’s a drawing of an execution. I wanted somebody who un - knew enough about life that they could capture the horror of what was going on. And so, I went with her. And, frankly, when this whole thing started, Alice had never been to Juarez. She went down there for about eight months, living on the line. But I feel my instincts were sound, that Alice brought the dead back, and now she makes the rest of us face what we've turned our backs on and have pretended isn't happening.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You wrote this book like a reporter traumatized by what he knows but can't write the way he'd like to write it. What was your frame of mind when you wrote Dreamland?

CHARLES BOWDEN: I wrote Dreamland in a fury, and the fury was at the American press and the U.S. government. I've been trying to leave the border for years because it’s damaging to me, because I'm tired of dead people, but I haven't been able to make it. I actually am, by some standards, a normal person. I feed birds, I garden, I like to cook. I don't need corpses. But what keeps bringing me back is I was - the way I was raised, you can't know this kind of slaughter is going on, you can't know that the destruction of a people is going on and pretend it’s not happening. When I wrote it, I hoped it would, you know, like get the demons out of my life. I guess you could say it was therapy on my part. Unfortunately, it didn't work, but it was a nice stab at it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I have to say I felt very shaken reading Dreamland. Now I can't read any stories about apprehended drug lords or recovered bodies in the same way. I do feel like if I haven't been down there, that your evocative prose has pushed my face into it, into the hopelessness. Was that your goal?

CHARLES BOWDEN: My dream is to invite a reader into a room and pour a nice cup of tea and then nail the damn door shut. I want him to look at a 40-year war of drugs that has created a police state in the United States, the largest prison population per capita on Earth, and slaughtered tens of thousands of Mexicans. I want him to taste it, not just have - read some policy statement. And that’s why it’s disturbing, because I want people to be disturbed. It seems to me it’s the only way things are ever going to change.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you consider Dreamland journalism?

CHARLES BOWDEN: I don't know. You know, I, I used to be a straight reporter. I worked for a Gannett newspaper. I've won a bunch of awards. I periodically revert and write what you'd call straight stuff. But I don't know if this is journalism, reporting or anything else. I know it is true, and I used whatever skills I have to make you not only understand what’s going on but for once to feel it, the way thousands and thousands and thousands of Mexicans have had to feel it. You have to be there. The kid’s on the ground, the blood’s pouring out of his head. He’s just been executed. And the women are screaming ‘cause it’s their son, their nephew. I've been there many times. And so, I tried to bring it home for other people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Charles, thank you so much.

CHARLES BOWDEN: Well, thank you. It’s been a pleasure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Charles Bowden is the author of Dreamland: The Way Out of Juarez, illustrated by Alice Leora Briggs.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP AND UNDER]