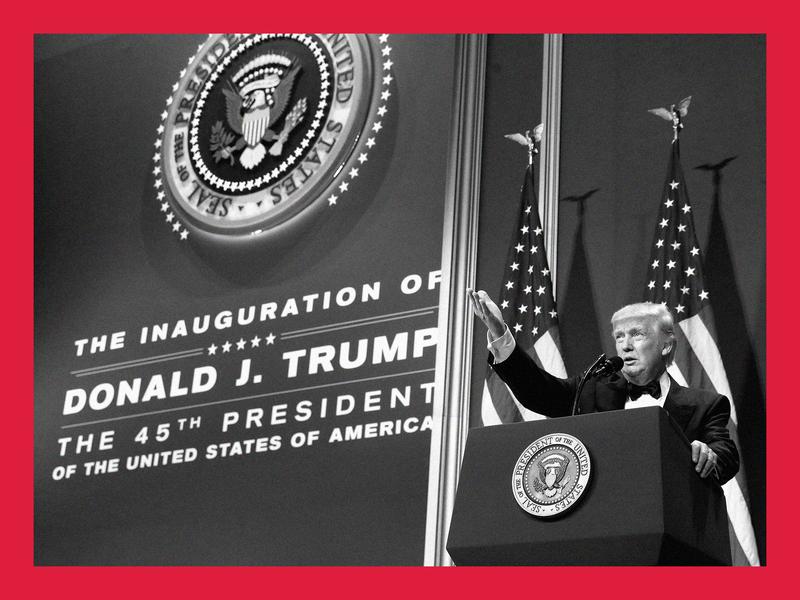

Trump’s Inauguration Paid Trump’s Company — With Ivanka in the Middle

[PLUCKY STRINGS PLAY]

ILYA MARRITZ: Hello, it's Ilya Maritz from WNYC, here with a Trump, Inc. extra. As you know, Trump, Inc. is the podcast from ProPublica and WNYC that digs deep into the business conflicts-of-interest around the Trump administration. And if you've been listening for a while, maybe you remember this man: Greg Jenkins, a planner of George W. Bush’s second inauguration, wondering how in the world Donald Trump's nonprofit Inaugural Committee managed to spend over a hundred million dollars.

GREG JENKINS: So they had a third of the staff and a quarter of the events, and they raised — what? — at least twice as much as we did. So, there’s the obvious question: where do they go? I dunno.

MARRITZ: No ideas?

JENKINS: No ideas.

[MUSIC OUT]

MARRITZ: That’s from an episode we ran back in March. If you haven't heard it, please go back and listen. This extra will make a lot more sense to you that way. Well, I am pleased to tell you, we do have some answers now. Some of the money went to the Trump International Hotel at 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C.

My colleague, Justin Elliott at ProPublica, and I — we just published a story about it on the Trump, Inc. website. Some of you have asked why we didn't do an audio story to match the online one. The answer is, this is an open investigation, and sometimes the news cycle nudges you to publish faster than planned. But we have more inauguration reporting to come, so stay tuned.

In the meantime, we wanted to bring you this conversation I had with WNYC’s Brian Lehrer. It's about the inauguration, but we also talked about General Mike Flynn and special counsel Robert Mueller. And you'll also hear Tony Romm, from the Washington Post, talking about Russian election interference using social media.

Here's Brian.

[MUSICAL FLOURISH PLAYS]

BRIAN LEHRER: Another wrinkle: WNYC and ProPublica are reporting, in recent days, on a previously unknown relationship between Trump's Inaugural Committee and the Trump D.C. hotel. Basically, Trump's company may have tried to overcharge his own inaugural committee to make more money for Trump himself, from the donors, to his swearing-in as President of the United States.

You can't tell the players without a scorecard these days, and helping us keep track of some of it today are WNYC’S Ilya Marritz, who reported the inaugural and Trump hotel story, and Washington Post correspondent Tony Romm, who reports today on this new Senate report about even more Russian interference before and since the 2016 election.

Hi, Ilya and Tony. Welcome to WNYC.

MARRITZ: Good to be here.

TONY ROMM: Thanks for having me.

LEHRER: Ilya, the Trump Organization did what?

MARRITZ: [LAUGHS] The Trump Organization, uh — [PAUSE] made money from the Inauguration. Uh, they held events. Uh, during inaugural week, there was a leadership luncheon, uh — I believe — a day before the inauguration. There was a — an after-party for the balls on inauguration evening.

Those events were paid for by the Presidential Inaugural Committee. And before that, as we documented, uh, there were large numbers of people working for the Trump Inaugural Committee, which is a nonprofit organization, basically formed quickly to put on a party for the president's inauguration — it’s done every four years.

Uh, there were people working for the “PIC,” as they call it, for the committee, staying at the Trump hotel. Now, we don't know what the — the Committee paid the Trump hotel ultimately. Uh, we'd like to get that number. But it was more or less acknowledged by Ivanka’s, uh, spokesman when we reached out to him. Uh, and he said she, uh — she sought a fair market price.

LEHRER: The headline on your story says, “Trump's inauguration paid Trump's company with Ivanka in the middle.” Tell us more about Ivanka Trump's role in your story.

MARRITZ: Yeah, this is so interesting and it was surprising to me when I got my hands on these emails, because I was not aware of Ivanka playing any role in the inaugural committee.

You have to remember, December 2016, there was talk that she might move to Washington — maybe her husband, Jared Kushner, would become an advisor to the President. That was sort of what we knew. What these emails show is that the inaugural committee was planning some events at the Trump hotel, and there was already some concern about the price.

And so Rick Gates — if you sort of reverse-engineer the chain — Rick Gates got in touch with Ivanka Trump. She connected him with a manager at the hotel who quoted back a price to the inaugural committee. That price was $700,000 for a ballroom and some additional spaces spread out over four days.

What's really interesting in this correspondence is that one of the key inaugural planners — how she responded to that price quote. Stephanie Winston Wolkoff is her name. And, uh, I’m just gonna quote from her email. “I wanted to follow up on our conversation and express my concern. These are events in the President-elect’s honor at his hotel. And one of them is with and for family and close friends. Please take into consideration that when this is audited, it will become public knowledge,” uh, public knowledge that some other venues were gifted and that this one charged — and may have charged a hefty fee.

LEHRER: And did they in fact, or did that email result in a negotiation downward?

MARRITZ: [CHUCKLES] We don't know.

LEHRER: Huh.

MARRITZ: We do not know. What I do know from other documents that I've seen is that, as late as early January, the inaugural committee still had — didn't have a final price from the Trump International Hotel. That was very late in the game. As far as I can tell most — or almost all of the other venues had already agreed on a price with the inaugural committee. You would think the easiest — the easiest negotiation would be with the President's family's own hotel, or you might really think that they would avoid his own hotel, just for appearances sake. That's not what happened.

LEHRER: And before we bring in Tony Romm from the Washington Post on some of these other moving parts, your story, Ilya, the WNYC-ProPublica story, came a day after a Wall Street Journal story about the inaugural committee now being the subject of a federal investigation. Do your two stories connect?

MARRITZ: I think they do. Uh, and I think that the place that they connect most closely is around this woman, Stephanie Winston Wolkoff, who had warned of, uh — of that high pricing at the Trump hotel, because it appears that the way that, uh, Southern District of New York investigators got onto this was from the Michael Cohen raid. Do you remember, back last April?

One of the things that investigators pulled out one of the spot — Michael Cohen places that they raided was a recording of a conversation between him and Stephanie Winston Wolkoff, the inaugural planner, in which she expressed concern over inauguration spending. That seems to have become the basis for this probe. Uh, the New York Times says that the probe is looking into foreign donors. The Wall Street Journal says it's a cash-for-access thing.

We still haven’t answered the question of where this $40 million or so — that’s not accounted for in the public filings — where it was spent and, frankly, there's now concerns about where it came from. So, my co-reporter on that story — Justin Elliott from ProPublica — he and I are definitely still looking into this. If you have tips, please find us. Get in touch.

LEHRER: And that's a criminal investigation?

MARRITZ: That — that's my understanding.

LEHRER: Tony Romm from the Washington Post, you’re a technology reporter. What’s this new Senate report, and what does it have to do with social media?

ROMM: Yeah, the new Senate report that came out this week is a really breathtaking look at the work on the part of Russian agents to try to manipulate the conversation on social media before, during, and after the 2016 election. Now, we knew from the past two years of investigation that Russian agents took to Facebook and Twitter and YouTube to spread messages with the goal of sowing social and political unrest.

What the reports show us, uh — released this week — is that it was well beyond these social media sites. It touched practically every property on the internet. And, in many cases, that content was viewed and interacted with at a much higher rate than we previously understood.

Instagram is a great example of this. We knew that there were millions of people who saw Russian-generated content on Instagram, but we didn't know until yesterday that that content had more than 187 million interactions. Those are things like likes on photos, and comments on those photos. And so it really just affirms the fact that Russian agents spread messages throughout the election. And in the minds of some lawmakers it signals that there are a lot of problems still to address in elections still to come.

LEHRER: Part of this story is of Russia targeting African Americans specifically, in what I think we can call a Russian effort at voter suppression to help Donald Trump. Yes?

ROMM: That’s exactly. Right. They really seem to have two goals when it came to African Americans — and, by the way, that wasn't even the only group targeted. In some cases, it was about sowing social and political unrest online by getting folks to fight over issues around race. And, in other cases, it was about — once they got those folks to interact with the content — deterring them from voting, whether it was suggesting that they shouldn't turn out to vote, or saying that their votes wouldn't count. or that voting itself wasn't a helpful way to affect political change.

Now we don't know at the end of the day if this actually had an effect on what people decided, whether they went to the polls or not, and so forth, but we do know that the content was pretty widely shared, and that it continued well after the 2016 election, as these Russian agents continued to push narratives that were favorable to Donald Trump while trying to stoke social and political conflict.

LEHRER: And listeners, we can take phone calls — any questions or comments you have, or, even as Ilya was inviting, uh, to help us report this story about the Trump Inaugural Committee and the Trump hotels, or maybe you want to help report the other story that, uh — that the Senate received a report on yesterday, um, about how maybe you realize now that you were targeted during the social — during the 2016 presidential election, um, on social media, or even since, as the Senate report says those Russian efforts to sow division in the United States are ongoing via social media.

212-433-WNYC with a question, a comment, or a story. 212-433-9692 for WNYC’s Ilya Marritz, who’s also the host — cohost of our Trump, Inc. podcast, and Tony Romm, technology policy reporter for the Washington Post.

Um, Tony, let me — let me stay with you. What's the part of this report that the Senate received about the ongoing needs nature of this since the 2016 election?

ROMM: Yeah. One of the important conclusions of this report was that the operations on the part of Russia continued after folks turned out and voted for Donald Trump. And it occurred in a few ways. In some cases, we saw Russian agents using those masqueraded accounts — using those bots and so forth — pushing narratives that the investigation launched by Robert Mueller was essentially a fraud, and that Mueller was compromised. There was even one post that was pretty resonant on Facebook that linked him to radical Islamic groups, which, obviously, is certainly not the case.

Uh, and in other cases, we saw Russian agents trying to stoke political and social conflict offline. You know, they weren't out there talking, uh, in favor of Hillary Clinton during the election, but after the election, they appeared to see an opportunity among her voters who are preaching the resistance — people who actively wanted to fight Trump's agenda on issues like immigration.

So they would take to a site like Facebook. They would join the — or create these protests around Trump's agenda. They would recruit real Americans to join those events, and then to spearhead the actual protests. And, in some cases, we know that the protests were carried out, whether it was outside the White House or out at Trump Tower, because we can see photos of those protests that were shared by the real participants.

And so it's an example to the researchers — and to many folks on Capitol Hill — that a lot of the conflicts that Russians tried to stoke online very much migrated offline. And so here we are in 2018, we just wrapped up a midterm election. We've got the 2020 election that seemed to start the day after the 2018 election. And there's a lot of concern that many of the troubles that were spotted in 2016 haven't been resolved, and that they could continue to get worse unless tech companies do better.

LEHRER: Steven in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Steven.

STEVEN: Hi, Brian. Thanks for taking my call. You are a national treasure. Um, I wanted to, uh, go more into this idea of, uh, that Russians were targeting, um, uh, the Black demographic. Uh, how would they know — I'm very curious how they would know exactly how and why to target, uh, the Black demographic. They must've gotten that information from somewhere, whether or not it's someone in a campaign or someone in a private business and, um, is — is that being investigated?

LEHRER: Tony?

ROMM: Actually, you actually don't need to know a whole lot to do that kind of targeting. And we see brands — like companies that want to sell you shoes, for instance — that take advantage of these tools in social media. If you want to target your message to a particular demographic online, the tools exist on these social media sites to focus your message and your ads. And in many cases, we saw them doing this on Facebook with advertisements.

You know, maybe they would put up an ad, uh, about a particular issue of importance to the Black community. Something like police brutality, for instance. A user would click on that ad, or they would hit the “Like” button on a particular post that resonated with them, and then they would continue to see more of that content. It's like, they — they — they — they hooked you in, and then you continued to see that.

Now, in other websites, you can't do a whole lot of targeting like that. Take YouTube, for instance. When you put up a video on YouTube, anybody who goes to that YouTube page is going to see it, unless you purchase an ad elsewhere that directs users there. But in that case, it was just putting together content that might be resonant with those communities, uh, with the hopes that eventually they would keep coming back to those channels.

So in many ways, this very sophisticated Russian operation took advantage of these targeting tools in social media that are available to practically everybody, that many businesses and many individuals have used to target their messages very specifically.

LEHRER: Does the Senate report — and Steven, thanks for your call — does the report suggest some of the brand-name tech giants were even less forthcoming to the government about how they were used by Russia than previously known?

ROMM: There’s a lot of frustration around that. I mean, remember, two years ago, when Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was asked about social media and its role in the 20— in the 2016 election, he said it didn't think that it swayed the outcome of the election. And now we know, two years later, that the posts that were put up by Russian agents most certainly had an effect on what people were sharing on the sites.

So, in one camp, you have lawmakers who say that those three companies were slow to spot what happened, and haven't turned over enough information for researchers to fully make a determination of what went down. They would like to see more data from those companies.

And in certain circumstances, lawmakers feel that companies just weren't sufficiently forthcoming. That's definitely the case with Instagram, where Congressman Adam Schiff, the incoming Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, says he doesn't think that any of the evidence suggested — that had been previously provided to the Committee — had suggested that the problem was as bad as it is.

And then you have an entire other stable of sites, like Tumblr and Reddit and Medium, things that folks maybe haven't even heard of, that had opera- had been operationalized as part of this effort. So there's a lot of concern that we've only really scratched the surface.

LEHRER: Ilya, Michael Flynn’s sentencing is today, for lying to the FBI about Russia, with this last-minute drama of Flynn and Trump saying Flynn was interviewed unfairly by the FBI in the interview in which he lied. And yet he's still pleading guilty to that lying. What will you be looking for in court today?

MARRITZ: Well, he's already entered the courtroom. I saw the footage this morning. Uh, so that should be coming down — actually really momentarily, is my understanding. Uh, the thing that's most interesting to me is actually the, uh — the charging document yesterday for two of Flynn's associates, which really spells out in great detail this Turkish influence campaign that Michael Flynn participated in in the summer of 2016. At the same time that he was becoming a prominent surrogate for Donald Trump, he was also strategizing with these two associates, uh, who were acting on behalf of the government of Turkey, uh, strategizing around how to get an extradition order for a Turkish cleric who is a legal resident in the United States. His name is Fethullah Gülen. Um, this document just — I mean, Mike Flynn is not referred to by name, but he's called “Person A,” uh, but if you read it, you get a very —

LEHRER: You can have a great lunch with Donald Trump. “Person A” and —

MARRITZ: [CHUCKLING] “Individual-1”!

LEHRER: — “Individual-1.” And, uh, who knows what, um, they may call Mike Pence by the end of dinner. Anyway, go ahead.

MARRITZ: Well, it just spells out in — in — in really breathtaking how, um, involved Mike Flynn was in this process, at the same time he was one of the most prominent people representing a major party nominee for president — president, and then transitioning to National Security, uh — uh, nominee. Um, he had — he had an opinion piece in The Hill on Election Day 2016. It's just breathtaking.

And so, you know, it seems that the special counsel, uh, is not asking — special counsel is not asking for jail time for Mike Flynn. And I think, today, a lot of people are asking, uh, “Why not, if he — if he did all this stuff?”

LEHRER: In your Trump, Inc. podcast, you basically follow the money that attaches itself to Trump's business interests. Here — and I don't know if it's tangential to Trump, Inc., or if it falls under your purview — but you have Paul Manafort — who you've you've reported on a lot, uh, because of his business dealings — Paul Manafort being paid by a foreign interest — the pro-Russia Ukrainians — at the same time that he's campaign manager for the guy who's about to become President of the United States.

And you have Michael Flynn, who's being paid to be an agent of Turkey at the same time that he's about to become National Security Advisor of the United States. It's incredible. And I'm sure it's never happened before.

MARRITZ: This is one of the big themes for us and it’s — it's really hitting me kind of hard this morning actually — is how open-for-business people in Trump world appeared to be in the summer of 2016. It's worth reminding ourselves that most people didn't think Trump was gonna win. So what they were playing for probably was influence in Hillary Clinton's Washington. Uh, the sense that a guy with a lot of popular support, um, was associated with some of these people, and those people were not going to be tarnished because at the time nobody knew that all of this was going to come to light and there was going to be a Robert Mueller. But it’s — it’s really breathtakingly similar. In fact, uh, the Turkish influence campaign — similar to an influence campaign that Paul Manafort set up for the Ukrainian government — flowed through — it's sort of a disguised entity. Like, they took steps to set up an entity in the Netherlands, so it would look like this money that was flowing towards Michael Flynn — I think it was close to $600,000 — that it would — that it would appear as if it was not from the government of Turkey. That’s straight out of Manafort's playbook.

Now. I don't know what kind of history those two men have together. I've never heard that they did, but you can see it's — it’s almost like a bat signal went out that summer that the rest of us couldn't see that said, “Yeah. Open for business. Come talk to us.”

LEHRER: You know what I don't know. Did Flynn's guilty plea also cover him covering up that he was a Turkish agent while entering as National Security Advisor of the United States?

MARRITZ: He only pleaded guilty to false statements to the FBI. He did belatedly register as a foreign agent, though, so that may have covered it. I'm not an attorney there. Um, this seems to be sort of the end of the line for Mike Flynn. And I think a lot of us are really curious to know what exactly are the beans that he spilled, because he had 19 interviews with the special counsel, and we know that he helped out with, uh, “redacted matters,” as the court filings show. There’s a lot of black redactions there.

[CREDITS MUSIC IN]

LEHRER: And consistent with how Robert Mueller has been working all along so far, none of it has leaked.

MARRITZ: WNYC’s Brian Lehrer with Tony Romm of the Washington Post and me. One note of housekeeping. Trump, Inc. is taking a short break from publishing new episodes while we work on a new season of reporting. We’ll be back in the beginning of next year. In the meantime, you can — no, you should — sign up for our newsletter to stay up-to-date with what we're working on. Just head on over to TrumpIncPodcast.org to get signed up.

I’m Ilya Marritz. Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC OUT]

Copyright © 2018 ProPublica and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.