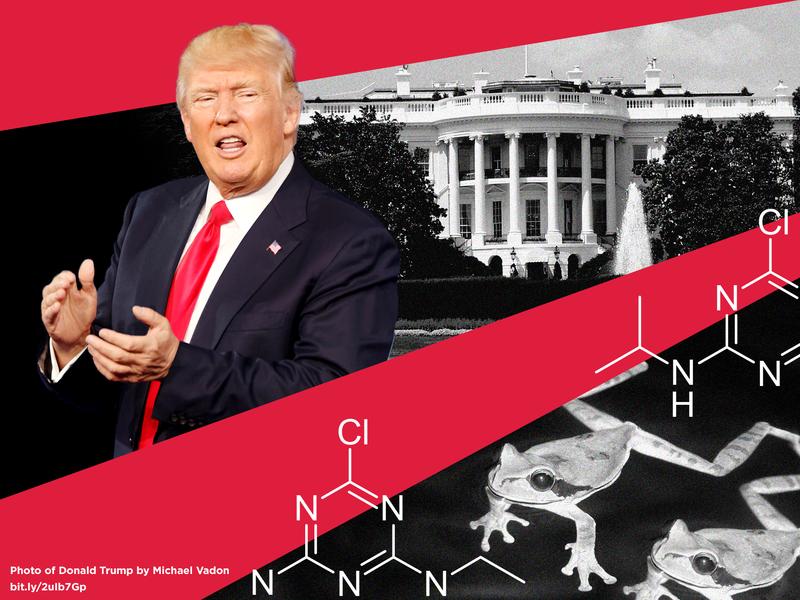

Trump, the Ex-Lobbyist and 'Chemically Castrated' Frogs

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: Here’s something we learned about the Trump administration, a lobbyist, and an herbicide that chemically castrates frogs.

[INTRIGUE-LADEN MUSIC PLAYS]

CLAIRE PERLMAN: The herbicide is named Atrazine, and it's made by this huge agribusiness company named Syngenta.

BERNSTEIN: This is Claire Perlman. She's a ProPublica research fellow — also, a former PI.

PERLMAN: And scientists have found that it's associated with low sperm counts in men.

BERNSTEIN: Atrazine has a more dramatic effect on frogs.

PERLMAN: Essentially, it can chemically castrate a frog and essentially turns it into a female frog. After they were exposed to Atrazine, the male frogs were able to give birth to frogs. Thus female frogs were …

BERNSTEIN: So it's been banned in Europe?

PERLMAN: It is banned in Europe. It's been banned in there since 2004.

BERNSTEIN: But it's not been in the U.S.?

PERLMAN: No. And the House of Representatives actually tried to pass a bill to ban it, but it did not get anywhere.

BERNSTEIN: One of the lobbyists who worked specifically to prevent that ban? A guy named Jeffrey Sands. He works for the Federal Environmental Protection Agency now. Claire found his lobbying records.

PERLMAN: And he was a lobbyist at Syngenta until the month he started at the EPA.

[MUSIC OUT, THEN, FROG RIBBIT]

BERNSTEIN: Like other Trump administration employees, Sands was required to sign an ethics pledge that's supposed to prevent him from working on any issues that he lobbied on in the last two years, or that relate to his former employer. But then he got an ethics waiver.

PERLMAN: He is allowed to work on issues that he's lobbied on in the last two years.

BERNSTEIN: He’s still not allowed to work on issues that substantially relate to his former employer.

PERLMAN: But, feasibly, he could work on Atrazine, which is also manufactured by other companies.

BERNSTEIN: The EPA initially did not disclose that Sands even had a waiver — until Claire asked about it. They gave a statement.

PERLMAN: [CHUCKLING] They said, “All EPA employees get ethics briefings when they start and continually work with our ethics office regarding any potential conflicts they may encounter while employed here.” Jeffrey Sands is no different.

[LOW DRONE PLAYS]

BERNSTEIN: In the 2016 campaign, Trump had a lot of disdain for influence peddling.

DONALD TRUMP: We are going to [CHANTING WITH THE AUDIENCE] drain the swamp.

BERNSTEIN: So did his supporters.

[THE AUDIENCE CHANTS, “DRAIN THE SWAMP”]

BERNSTEIN: A couple of weeks before election day, he put out a five-point plan to limit lobbying by former public officials.

TRUMP: Decades of failure in Washington and decades of special-interest dealing must and will come to an end. [CHEERING]

BERNSTEIN: Trump even told CBS’ John Dickerson during the campaign he'd look to ban former lobbyists from his administration.

JOHN DICKERSON: Will you say, “No lobbyists will work for me, and no big donors”? Just in keeping with your argument that people who give and who work the system are trying to corrupt the system. Do you have that kind of —?

TRUMP: I will have no problem with it, honestly, because, you know, for the most part, uh, the — the money that's coming in — you know how much I've turned down? I have turned down. I’ll bet you, if I wanted to do a super PAC … [FADES DOWN]

[TRUMP, INC. THEME MUSIC PLAYS]

BERNSTEIN: Hello, and welcome to Trump, Inc., a podcast from WNYC and ProPublica that digs deep into the mysteries of the Trump family business. I'm Andrea Bernstein from WNYC.

Today on the show, Trump Town. It's the created by ProPublica that Claire Perlman used to find out the lobbying history of Jeffrey Sands, the Trump EPA appointee.

[MUSIC OUT]

BERNSTEIN: And it's a tool you can use, too! More on that in a bit. This episode is a little different from what we've been doing so far. We’re going to focus more broadly on the many business interests tangled up in the Trump administration. Turns out, Trump hasn't banished former lobbyists. He's surrounded by them. ProPublica is working on keeping the count, and Eric Umansky is here to talk about what they've found so far and what we hope to find with your help.

[MUSICAL FLOURISH]

ERIC UMANSKY: Hello, Andrea.

BERNSTEIN: So, Eric, we're talking about Trump Town, which is a tool that ProPublica put together. It took you a year, really, assembling data from across the administration and it began on a Friday night about a year ago.

UMANSKY: Right. So, um, there's a phenomenon called the “Friday night news dump,” when administrations put out news that they'd prefer, all things being equal, you didn't really pay much attention to. So, one Friday night, uh, in the spring — I think it was late Friday afternoon, to be fair — we got a message saying that the White House was going to be releasing — in a great act of transparency — the financial disclosure forms for people who work at the White House. And this is a thing that White House employees have long been required to do, to literally fill out a form that lists what stocks you own, what investment you owns, what debts you have. And previous administrations — the Obama administration, uh, for example — put all that online.

The Trump administration decided that they had a new innovation, a new way of doing it. And what they announced on that Friday afternoon was that, instead of putting it online, they were going to create a form that you could fill out and request White House official’s financial disclosure forms by name. But there was a trick, and the trick was, they didn't actually release the names of the White House officials who filled out financial disclosure forms.

BERNSTEIN: Some of these are people that we know the names of, right? Like, people that are gone now.

UMANSKY: We know Spicy. We know —

BERNSTEIN: Steve Bannon!

UMANSKY: — the whole list. Yep!

BERNSTEIN: A lot of people, but we don't know a lot of these people's names, right?

UMANSKY: Right. There were — there were well over … I think the number was something like, you know, on the order of about 180. You know, you and I follow this stuff pretty closely. I don't know. We could maybe name — what? A dozen, maybe two dozen — if we were lucky. How are you supposed to ask for that financial disclosure forms of people you don't know who they are?

So Tracy Weber, an editor at ProPublica, had the idea, “Why don't we call up our friends at other news organizations and literally create a Google spreadsheet where we collectively list all of the names that we know? Maybe, you know, Eric Lipton at the New York Times knows some names of people we don't know, and vice versa. Put all that together, and put all of the disclosure forms there for everybody.”

BERNSTEIN: So you called this Transparency Battleship.”

UMANSKY: Yeah.

BERNSTEIN: We’re talking about the board game where you, like, have to guess where the battleship is.

UMANSKY: Right, ‘cause you would say, “John Smith?”, and they would say, “Miss.” And you'd say, “John Smithton?” and they would say, “Hit!” Right? I mean, you know, you just had to guess the names. And then you would — if you were so lucky — eventually — and by the way, this was, I wouldn't say the turnaround time on this broke any customer service records for, uh, speediness, right? But eventually you would get the names back, and then we would dig into them.

By the way, I just made up the name John Smithton. I don't believe there's anybody actually by that name in our database.

BERNSTEIN: So this began to result in some stories right away.

UMANSKY: Yeah, we — we had, um, a — you know, you started to get the sense sometimes, [IN A GOOFY VOICE] “Well, you know, we're the professionals, and we really dig deep, and we know what to look for.” And, you know, we were definitely looking through some stuff, but it was all out there for anybody to look at, too.

BERNSTEIN: And a reader pointed out that in one of the President's ethics disclosure forms, he had listed the sale of a condo on Central Park South for just a few hundred thousand dollars.

UMANSKY: Right, exactly. Yeah. And why would you be selling a condo there for just a few hundred thousand dollars? And so, well, who did he sell it to? He sold it to an LLC, which, uh, the key thing here is a way to often shield buyers and owners of things, right? So we didn't know who the LLC was.

BERNSTEIN: Turns out the shell company was actually Eric Trump's. He was looking to combine three apartments into one, and the citizen journalist found Eric’s signature on some documents in New York City's online land records system.

UMANSKY: So it turned out Donald Trump had sold a condo to his son at a major discount that would normally trigger gift taxes, because you're basically giving a gift to a family member. Totally legit to do. But, in this case, he didn't pay gift taxes —

UMANSKY: — and he basically had an end run such that it was legal, but a thing worthy of paying attention to.

[MUSICAL FLOURISH]

BERNSTEIN: So, you also began to tease out these broad themes — not just these specific stories, but things you saw patterns of. One of them is something we were talking about at the top of the show, these ethics waivers. Basically, people getting permission to work on things for the administration that they had lobbied for or worked on beforehand. Give us a broad sense of what you began to learn about these waivers.

UMANSKY: You know, the waivers are … Well, first, there are the ethics rules themselves, right? So that sounds like, [ANOTHER GOOFY VOICE] “Well, those are august things that, you know, exist in concrete, or chiseled in stone somewhere.”

PRESIDENT TRUMP: [OVER THE SOUND OF CAMERAS CLICKING] So this is a five-year lobbying ban. And this is all of the people. Most of the people standing behind me will not be able to go to work [LAUGHTER] but … [FADES OUT]

UMANSKY: He could then give people waivers on the own ethics rules that he had passed, right? So he passes ethics rules that, frankly, aren't so tight — they’re watered down from the previous administrations. And then, the administration gave out these ethics waivers without actually disclosing them.

So we reported on that, and on a whole bunch of people — in fact, we started finding so many cases on lobbyists who were hired to work in agencies that they had once lobbied that it became overwhelming. It was such a clear trend.

BERNSTEIN: So there was something else you told me about this week that made me go, “Wait, what?”

UMANSKY: That's your — that's your ‘mark phrase. That’s your phrase.

BERNSTEIN: And that's about Special Government Employees. So what is that?

UMANSKY: So, there's a thing called a Special Government Employees — SGEs — that have actually been around for 50-plus years in some form or another. And what it is, is a special provision that allows people to work in private jobs at the same time they're working for the government, right?

So we're talking about these, you know, people who used to work in industry and then go on to work in the federal government. These are people who are actually working in private industry while working in the government. And that's something that, you know, has been used before. We don't really know the scale it was used before. We actually, at ProPublica, wrote a story a number of years ago about somebody whose name you would recognize who was once a Special Government Employee. That would be Huma Abedin.

BERNSTEIN: She was, of course, a senior official in the State Department, then in Hillary Clinton's campaign. She is also famous for being married to Anthony Weiner. While she was at the State Department, she also worked for a private consulting firm.

NEWS ANNOUNCER: [OVER INTRIGUE MUSIC] Abedin worked for multiple private sector companies while working at the State Department, including work for a consulting firm run by a close Clinton ally and simultaneously getting paid by the Clinton Foundation.

UMANSKY: So it's a thing that's happened before. What we found is dozens and dozens of Special Government Employees working in various industries at the same time that they have jobs in the administration. Now, there can be reasons for that, right? But that seems like a thing that is particularly worthy of scrutiny.

BERNSTEIN: What’s an example of a Special Government Employee in the Trump administration?

UMANSKY: Well, the instance that I found most interesting is Wendy Teramoto, who used to work at now-Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross’ investment firm. And she now works at the Commerce Department. And for a long period — we actually don't know because the administration won't say exactly how long — she was working at both, at once. Now, Wilbur Ross’ firm has investments all over the world — in steel companies, in shipping — that have all sorts of partners in all sorts of places.

BERNSTEIN: And the Commerce Department, among other things, promotes trade abroad, and deals with things like trade PACs.

UMANSKY: So you are literally representing two different interests at the same time.

BERNSTEIN: And Ross, the Commerce Secretary, has actually credited her with negotiating some big deals.

NEWS ANCHOR: Who did this deal? Did you do it personally?

SECRETARY WILBUR ROSS: Well, I did, and Steven Mnuchin, the Treasury Secretary — we’re the co-heads of the economic dialogue. But, really, a lot of the work was done by Wendy Teramoto, my chief of staff.

UMANSKY: And when we reached out to her and — and Wilbur Ross, the Commerce agency, you know, said exactly that, that they've been quite careful and there haven't been problems. Again, there are roughly 70-odd cases of this. And those deserve to be looked at.

[MUSICAL FLOURISH]

BERNSTEIN: So, we have all these waivers, we have all these Special Government Employees. I think it's worth saying that this is happening in the context of an administration where, from the top — from literally the President on down — there's a sense that it is perfectly fine to, as President Trump says, “I could run the country and run my company at the same time.” His son-in-law, his daughter — there are a number of people in the administration who have not divested from their personal financial interests while also working in senior level government positions.

And now we're seeing a level below that, where there seems to be an attitude that there are certainly many instances where it's okay to work for a company and work for the country at the same time.

UMANSKY: Right. And it may be in fact that there are perfectly appropriate instances of that. It is not obviously immoral to, uh, come from an industry or obviously, um, uh, problematic or incorrect to come from an industry with — have industry expertise and then go to work for government and things involving that industry.

You might have, you know, particular skills — particular insights that could be helpful. The thing that I think is important to remember and — and keep in mind is, that can be perfectly the case. We should have the ability to look at each of these cases, to have each of these cases public, and to look for ourselves — to see what's happening, to see what the backgrounds are, and for the public to make their own judgments, right?

One — one of the things here has been the persistent secrecy and opacity that we've seen every step of the way. If the business of the administration is business and — and that that's a fine thing. “Remove the red tape and it's going to help the economy and so forth.” That is all a perfectly plausible argument and position to take. What you then should do is, let it be judged on its merits. Let's see what's happening, where it's happening, why it’s happening.

[MUSIC PLAYS SOFTLY UNDERNEATH]

BERNSTEIN: Okay. So this is where Trump Town comes in, because this is what you've done. You have made that possible for everyone to do, by gathering together all of these streams of information and disclosures and you have an ask now that you have gathered together all this information.

UMANSKY: We have multiple asks. So we took all of these documents that we were getting over the course of nearly a year — and of the financial disclosures and lobbying forms and all sorts of stuff — and put it all together so that you can search one name, in one place, find all the associated documents.

[MUSIC OUT]

UMANSKY: Um, or you could do things like say, “Show me all the Special Government Employees that you're aware of, or all the people in this agency and that agency.”

So it's an incredibly powerful tool in that there are, I think, something like 2,500 people in there. And 2,500 people is more than we can go through. So what are we talking about in specifics? I think there are three particularly useful things that people could do. We're actually publishing a — what we call a “reporting recipe,” so that you can sort of dig into this step-by-step.

But nevertheless, I'm going to lay it out right now. The three things in particular where you can find valuable information, we think —

BERNSTEIN: Don’t worry! You'll be able to find all of this online at TrumpIncPodcast.org.

[GUITAR-DRIVEN MUSIC PLAYS]

UMANSKY: One is to dig into people's financial disclosure forms and to figure out, um, you know, you'll say, “Well, they have a holding in XYZ, LLC. Well, who owns — who else is a part of XYZ, LLC? And what the hell does it own?” There are ways that you can pierce the secrecy of LLCs with not such complex Googling. And we have details on there. So that's one thing that you can do. And then you can simply share that with us, or dig in further and try to figure out the import of it.

Another thing that you can do is look up all the Special Government Employees that we were mentioning before, see what their backgrounds are, see their own lobbying records — which you can also pull up — and compare it to what their jobs are now. That would be enormously useful.

And then a third thing that you can do is get the waivers that we've been talking about — these ethics waivers.

So, go through and ask agencies what waivers — and, by the way, this is a thing that's like, you know, rinse, wash and repeat, right? But the situation could be different now. What’s to say that waivers weren't issued yesterday, or the day before? This is a thing that requires constant scrutiny and, frankly, accountability.

[MUSIC OUT]

BERNSTEIN: 2,500 mysteries out there. Help us solve them. Thanks, Eric.

UMANSKY: Thank you.

[CREDITS MUSIC IN]

BERNSTEIN: If you want to join us and do your own investigating, you can go to our website, TrumpIncPodcast.org. If you find something interesting, we'll share your scoop.

This episode was produced by Meg Cramer. The associate producer is Alice Wilder and engineers are Wayne Schulmeister and Bill Moss. The editors are Charlie Herman and Eric Umansky. Terry Parris Jr. is ProPublica's Editor for Engagement. Jim Schachter is the Vice President for News at WNYC, and Steve Engelberg is the Editor-in-Chief of ProPublica.

The original music is by Hannis Brown. Additional support for WNYC was provided in part by the Park Foundation. Huge things to ProPublica’s Scott Klein, Derek Kravitz, and Al Shaw for a year of Freedom of Information requests, document collection, and putting together the app Trump Town.

TRUMP: And they know this should be done, but they're not going to do it. But they'll do it if I get in. I'm going to, number three, expand the definition of lobbyists, so that we close all the loopholes that former government officials use by labeling themselves as “consultants” and “advisors.” When we all know that really what they are is lobbyists, right. Make a lot of money. There'll be a lot of pushback in that one, but I'm going to get it through. I really believe it.

[MUSIC OUT, AS A FROG QUIETLY RIBBITS]

Copyright © 2018 ProPublica and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.