Block The Vote

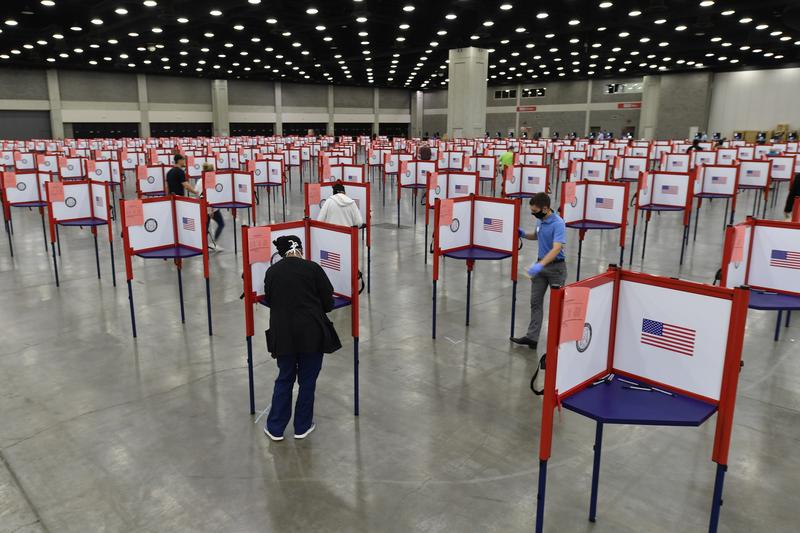

( AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley, File )

Trump, Inc.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: With a lawyer from the conservative Heritage Foundation whose theories about vote fraud have been discredited over and over again. Here's Mike Spies.

MIKE SPIES: A bare minimum what you need in this country is for everyone to believe in the validity of an election. That's the difference between a successful state and a failed state. And these meetings work directly against what makes a successful democracy and a successful election.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: We'll hear more about that story later this episode. Meg Cramer takes it from here.

MEG CRAMER: The first thing you should understand about vote fraud is that it is extremely rare. This has been documented over and over again. Even so for years, it has been common for Republicans to raise concerns about fraud as a justification for limiting access to the polls. ProPublica is Jessica Huseman covers voting. She'll be one of our guides this episode. Back in 2016, Jessica noticed that Trump was talking about vote fraud in a very different way.

JESSICA HUSEMAN: So Trump was really the first Republican candidate for president that took these concerns with him on the campaign trail and called into question the literal validity of the election and said well, you know, if I don't win, it's going to be because I was robbed and not because I lost the election.

(VIDEO CLIP PLAYING)

DONALD TRUMP: Illegal immigrants are voting. I mean, where are the street smarts of some of these politicians? They don't have any is right. right. So many cities are corrupt and voter fraud is very, very common. The following information...

JESSICA HUSEMAN: Like, that's a level of distrust and outward questioning of the Democratic process than we've ever seen in a president.

MEG CRAMER: Then Trump did win the election, but he didn't stop talking about fraud.

(VIDEO CLIP PLAYING)

DONALD TRUMP: You look at the dead people that are registered to vote who vote.

MEG CRAMER: Right after he was inaugurated, The Washington Post reported that in a meeting with congressional leaders Trump claimed without evidence that three to five million people had voted illegally inflating Hillary Clinton's totals. By telling this lie, Trump could claim that maybe he had not lost the popular vote.

(VIDEO CLIP PLAYING)

DONALD TRUMP: And we're going to do an investigation on it.

DAVID MUIR: Three to five 5 million illegal votes.

DONALD TRUMP: Well, we're going to find out, but it could very well be that much. You have...

MEG CRAMER: Trump formed the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity to bolster his fraud claim. It didn't last long. Here's Jessica.

JESSICA HUSEMAN: Trump disbanded it not even six months after he founded it, and it had its first meeting. It only ended up having two meetings before it embarrassed itself into oblivion.

MEG CRAMER: Did it ever publish any findings?

JESSICA HUSEMAN: No.

MEG CRAMER: Trump's claims about illegal voting persisted. Here he is in 2019 speaking at a student conference hosted by the conservative nonprofit Turning Point USA.

(VIDEO CLIP PLAYING)

DONALD TRUMP: They vote many times not just twice, not just three times. They vote - it's like a circle. They come back. They put a new head on. They come back. They put a new shirt on. And in many cases, they don't even do that. You know, what's going on. It's a rigged deal.

MEG CRAMER: There had been no evidence of widespread voter fraud in the 2018 elections either. In this election, Trump has a new story about voter fraud. It began to take shape at a coronavirus briefing on April 7 when he was asked a question about the Wisconsin primary.

(VIDEO CLIP PLAYING)

DONALD TRUMP: You know, mail ballots, they cheat, OK? People cheat. Mail ballots are very dangerous things for this country because they're cheaters.

MEG CRAMER: As states across the country, we're trying to figure out how to safely administer elections, Trump who votes by mail himself is dredging up his unfounded claims about voter fraud tailored to our new COVID reality.

(VIDEO CLIP PLAYING)

DONALD TRUMP: The mail ballots are corrupt in my opinion. And they collect them. And they get people to go in and sign them. And then they they're forgeries in many cases. It's a horrible thing.

MEG CRAMER: Vote by mail is not inherently fraudulent. Trump kept saying it was.

JESSICA HUSEMAN: People think that they understand how vote by mail works because they have both voted and mailed something.

MEG CRAMER: Yeah, that's me. I vote. I send mail. I feel like I know how those things work.

JESSICA HUSEMAN: And they don't see that there is like a whole organizational structure that is opaque for a reason. Like, they don't know how ballots are counted. They don't know how ballots are stored. They don't know how mail-in ballots are organized or the security protocols that our present every step of the process. And so when you break those things down for people and you explain it to them, then they're much less likely to believe all of this stuff about fraud and how possible it is.

MEG CRAMER: Turns out, if you want to convince people that your conspiracy theory is true, it helps if your conspiracy theory is about something that seems so basic we take our understanding of it for granted. This summer, Trump's campaign took his talking points about widespread voter fraud to a new venue court. On June 29, the campaign filed a lawsuit in Pennsylvania to prevent election officials from setting up secure drop boxes where voters can return mail ballots directly. The lawsuit calls the shift to mail-in voting, the single greatest threat to free and fair elections. Since June, Trump's campaign has gotten involved in at least a dozen voting lawsuits across the country seeking restrictions on mail-in voting. In Arizona and Ohio, plaintiffs have challenged barriers to vote by mail asking for more time to correct their mail-in ballots if they forget to sign the envelope or for more secure Dropbox locations. The Trump campaign went to court to get involved in these cases to defend restrictive voting laws. In legal papers, Trump's lawyers argued they wanted to ensure, quote, "fair and orderly elections conducted in accordance with established rules." In other states, the Trump campaign is challenging emergency election plans. In lawsuits filed in Montana and New Jersey, the campaign claims that plans to mail ballots directly to registered voters guarantee illegal voting, that fraudulent invalid ballots dilute the legitimate votes of honest citizens.

MYRNA PEREZ: It is disappointing that a presidential campaign has come on the side in a clear and unmistakable way of putting barriers in front of the ballot box.

MEG CRAMER: Myrna Perez is director of the Voting Rights and Elections program for the Brennan Center for Justice at the NYU School of Law. Documents show that Trump's re-election campaign has spent over $17 million on legal expenses so far, more than any past presidential campaign. We don't know exactly how much of that has gone to the voting lawsuits. But we do know that since June the campaign has paid over a million dollars to firms working on those cases, including $115,000 to a firm run by former White House ethics lawyer Stefan Passantino. It's his firm working on the Pennsylvania lawsuit. Joe Biden's campaign has spent $1.8 million on legal services. The campaign is not a party in any of the lawsuits about restricting mail-in voting. Perez says the Trump campaign is having a hard time making its voter fraud argument stick in court.

MYRNA PEREZ: Well, they're not having much traction in the courts because it's poppycock. It's rubbish. Like, they're not producing evidence that demonstrates that these concerns are well-founded at all.

MEG CRAMER: For example in Arizona, the campaign joined a lawsuit in which the Arizona Democratic Party wanted voters to have more time to correct their mail-in ballots if they forgot to sign them. The campaign wanted to maintain a tighter deadline. In that case, a judge ruled that state election officials have to give voters more time. There's no evidence the judge said that tighter deadlines prevent fraud. The Trump campaign and other defendants appealed. Another example, in Pennsylvania, a federal judge ordered the Trump campaign to provide evidence to back up its claims about the dangers of voter fraud, quote, "and if they have none state as much." That's the case where the campaign called the shift to mail-in voting the single greatest threat to free and fair elections. The campaign submitted a 524-page document, which according to the new site The Intercept did not include any examples of mail-in vote fraud. The federal judge put that case on pause until a similar case was decided in state court. In that case, Pennsylvania's state Supreme Court issued a ruling in favor of several provisions that make voting by mail easier, writing that claims of heightened election fraud involving mail-in voting are unsubstantiated. The pause on the federal case has been lifted, and the case is ongoing. There's also Nevada where the Trump campaign filed a lawsuit challenging that state's expansion of mail-in voting. On September 18, a judge dismissed the lawsuit calling the campaign's claims about the dangers of vote fraud impermissibly speculative. The judge wrote not only have plaintiffs failed to allege a substantial risk of voter fraud, the state of Nevada has its own mechanisms for deterring and prosecuting voter fraud. The Trump campaign has 30 days to appeal. Perez pointed out that these lawsuits have consequences beyond the resulting legal decisions.

MYRNA PEREZ: One, they're distracting to the election administrators who really need to be in the business of figuring out how they're going to provide voters good customer service on election day and not responding to lies about voter fraud.

MEG CRAMER: She says these lawsuits end confusing voters.

MYRNA PEREZ: The media, no disrespect intended, likes to publish them, likes to talk about them. And so voters end up not understanding what the state of the situation is and what the rules are and what it means for them.

MEG CRAMER: This has happened before. In 2016, a court case over a Texas voter I.D. law wasn't resolved until right before voting began. Voters and poll workers were confused about the details of the new law. Some polling places didn't have enough time to update their signage. It was bad enough without a global pandemic. Now almost every state is expanding access to mail-in voting to make voting safer.

MYRNA PEREZ: It bedraggles our election system. It bedraggles our democracy to have politicians at very high levels call into question practices that every state in the country uses and the country's been using since the Civil War. I really, really think that our democracy is going to be damaged by casting doubt on the outcome of an election that hasn't happened yet and discrediting a way of voting that many, many Americans will be using. Some of whom have been using that method for a really long time and some of them have to because of health concerns.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: The Brennan Center's Myrna Perez speaking with Trump Inc's Meg Cramer. The Trump campaign did not provide a statement for our story. There's such a high volume of messaging from Trump, his attorney general and his campaign that it's easy to forget that no president in modern history has assaulted the very mechanism of democracy like this before. We checked with ProPublica's Jessica Huseman. What role is the president supposed to play?

JESSICA HUSEMAN: The president really is supposed to play no role in any of this is the right answer to the question. Like, the president as the person who is in charge of American democracy should be reinforcing trust in the system because the system is inherently trustworthy. And that's really not overseeing. We're seeing a president sort of engage in the nitty gritty of ballot distribution, which is unique and then call into question the very system through which he was elected.

(MUSIC PLAYING)

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: We'll be right back.

(MUSIC PLAYING)

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: We're back. Around the beginning of the year, our colleagues at ProPublica set to work on a story about a lawyer from the Heritage Foundation who promulgates conspiracy theories on voter fraud.

(VIDEO CLIP PLAYING)

HANS VON SPAKOVSKY: All we have to do is look at the many cases, proven cases of absentee ballot fraud to understand that the problem with absentee or mail-in ballots is there the ballots that are most vulnerable to fraud, to being stolen. And they also...

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: Hans von Spakovsky who is well known to ProPublica's Jessica Huseman.

JESSICA HUSEMAN: Hans von Spakovsky is a longtime voter fraud conspiracy theorist, and he got his start like many people who are now doing strange things in the world of voting in the 2000 election.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: After that, he went to work for the Justice Department under President George W. Bush.

JESSICA HUSEMAN: He became such a controversial figure that towards the end of his tenure on at the DOJ he attempted to be nominated to a position on the FEC. And it went nowhere.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: It was after the Federal Election Commission post went nowhere that von Spakovsky joined the Heritage Foundation. Voter fraud was his main brief. He's been talking about it for a long time. Here he was in 2012, for example, at a debate over voter ID laws on PBS with host Gwen Ifill.

(VIDEO CLIP PLAYING)

GWEN IFILL: What is the problem that these new laws are attempting to fix?

HANS VON SPAKOVSKY: They prevent a series of things. For example, impersonation fraud at the polls, voting under fictitious voter registration names of people who've already died, voting by illegal aliens. And there's been plenty of cases...

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: So his work has been judicially discredited, right?

MIKE SPIES: Oh, yes.

JESSICA HUSEMAN: Oh, yes.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: In 2018, von Spakovsky was called in to be an expert witness in a federal trial over a Kansas law that required proof of citizenship in order to vote. Von Spakovsky was there to present data on noncitizen voting.

JESSICA HUSEMAN: The judge basically dismissed all of his testimony, called it cherry picked, called it biased. Said that he was more of an activist rather than an unbiased expert witness. And her opinion basically said that she gave his testimony no real credence in her decision.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: The judge, Julie Robinson, wrote von Spakovsky's statements were premised on several misleading and unsupported examples and included false assertions. She said his generalized opinions about the rates of noncitizen registration were likewise based on misleading evidence and largely based on his preconceived beliefs about this issue, which has led to his aggressive public advocacy of stricter proof of citizenship laws. Von Spakovsky maintains a database of what he calls some 1,300 cases of vote fraud.

MIKE SPIES: But to be clear, those 1,300 cases go all the way back to 1982.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: This is ProPublica reporter Mike Spies.

MIKE SPIES: So that means that we're talking about 1,300 cases over a period of time when literally billions, billions of ballots have been cast. Basically by his own data's admission, it is virtually a non-existent issue.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: The Heritage Foundation did not make von Spakovsky available for an interview. In a statement, a spokesperson said the Heritage Foundation is committed to making sure elections are free and fair. Every eligible voter's vote should be counted and not cancelled out by fraudulent acts. The Spokesman Greg Scott did not answer further questions. After the ruling in the Kansas trial, Jessica continued to report on voting. She noticed something. Even after the judge discredited von Spakovsky's work, at the twice a year conferences attended by most state level election administrators the most conservative members would disappear for a while to private meetings with von Spakovsky. This year as it became clear von Spakovsky remained influential, ProPublica began to try to learn more about these invitation only meetings. They started sending out Freedom of Information requests to certain pivotal states - Florida, Ohio, Nevada, Georgia, Missouri and so on.

MIKE SPIES: Then it was, like, really just a matter of days before - I think the first batch I got back was from Missouri. And it immediately showed that the meetings were real.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: Mike says early on he and Jake got a document that provided a roadmap for their research.

MIKE SPIES: And the thing that guided us was we had gotten a roster of attendees to one of his in-person events that took place in 2019, which gave us a pretty good indication of who was - I mean, these are people that are you know to be clear traveling all the way to Washington D.C.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: Von Spakovsky's meetings were attended by state, secretaries of state. These officials are often partisan but their job is to ensure the integrity of their state's elections.

MIKE SPIES: The purpose of the meeting was essentially to sort of jointly strategize.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: And, again, only Republican officials were invited to the meetings. Up until 2020, they met basically a couple of times a year in Washington. Republican congressional staffers sometimes came and on at least one occasion so did officials from the Justice Department, Trump appointees.

MIKE SPIES: That event that we had the roster, from the 2019 one, as it happened also included the two top officials in the Department of Justice's Civil Rights Division, which is responsible for essentially safeguarding the franchise. I mean, it's - I couldn't emphasize enough how crucial it is that that division remained apolitical.

JESSICA HUSEMAN: I think one of the things that concerns me most is that these meetings are so exclusive and that participants are told not to take notes. They don't want records of these meetings going around.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: But some officials did keep records. Jake and Mike got some of them.

MIKE SPIES: And then a few months later just out of curiosity, we just checked back in. And it turned out that there were new meetings that were happening.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: As the pandemic heated up and with it concerns about in-person voting, Mike and Jake found the meetings were occurring more frequently. One of the emails they obtained was from the Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. Yes, put it on my schedule, he wrote.

MIKE SPIES: So it seemed like there was an effort, an urgency, you know, like something had changed. Like, it was already important obviously to hold these yearly events. But now that we're actually getting close to election and this election is going to be carried out in a way that's different than other elections it seemed for von Spakovsky more important to make sure that everybody was on the same page.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: Mike and Jake found an example of what it looks like for elections officials to be on the same page as von Spakovsky. In July, a voting rights group in Ohio publicly advocated that more absentee ballot drop boxes be placed at schools, libraries and other public places across the state's 88 counties so that voters could vote more easily. According to a July 15 email, one of Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRosa's deputies immediately called and emailed von Spakovsky asking to discuss the matter. Weeks later, LaRosa announced he did not have the authority to add more than one ballot receptacle per county. Voting rights advocates say that will make it harder for people who want to avoid the crowds of a polling place to cast a vote. They're challenging the decision in court. Just this August, von Spakovsky invited officials to another meeting. The invitation said the convening would, quote, "gather the chief state election officials together to strategize on advancing their shared goal of ensuring the integrity of the elections they administer in their home states." This time, a new official joined the group, a Trump appointee from the Department of Homeland Security.

MIKE SPIES: This person is someone who had a longtime association with Hans von Spakovsky. They have worked together. They even taught classes together at George Mason University. And this person whose name is Cameron Quinn was presented as the, quote the email, "the new liaison to the election community." What makes that disturbing is, one, that was literally and continues to literally be not true. Two, she didn't have permission to be on the phone.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: She participated without her bosses knowing.

MIKE SPIES: And three, because the call is only for Republican secretaries of state, as far as this one group of secretaries knows, this person is the liaison to the election community.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: We don't know why Quinn represented herself as a channel for elections officials when people familiar with her role told Mike and Jake that wasn't her purview.

MIKE SPIES: That's really, really weird. And all the questions surrounding the weirdness of that event have not been answered yet.

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: A DHS spokesperson confirmed Quinn was not yet an employee of the division at the time she participated in the meeting but declined to answer additional questions. Other people at the meeting also declined to answer ProPublica questions. What are those questions?

MIKE SPIES: So the major question is for all of them, why are you participating in these meetings? If you know that his work is unreliable, if you know that the work has been undercut, if you know that much of it has been knocked down even based on his own data, what is the value in continuing to do this for years now? What is - what are you using information from Hans von Spakovsky?

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: There are just weeks to go until the election, and there is so much we still don't know.

(MUSIC PLAYING)

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: This episode was reported by Meg Cramer, Jake Pearson, Mike Spies and Jessica Huseman and produced by Katherine Sullivan. The editors were Jesse Eisinger, Nick Varchaver and Dan Golden. Jared Paul is our sound design and original scoring. Hannis Brown wrote our theme and additional music. Matt Collette is the executive producer of Trump Inc. Emily Botein is the vice president of original programming for WNYC, and Steve Engelberg is the editor in chief of ProPublica. I'm Andrea Bernstein. Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.