The Accountants

( Richard Drew / Associated Press )

SUPREME COURT BROADCAST: Oyez, oyez, oyez.

ILYA MARRITZ: Something new is happening in the United States Supreme Court — something that has never happened before. Oral arguments, broadcast live. Anyone can listen in.

SUPREME COURT BROADCAST: All persons having business before the honorable Supreme Court of the United States are admonished …

MARRITZ: It's a coronavirus thing. The justices, and the lawyers, and everyone — they’re in their homes or offices, connected through gadgets.

SUPREME COURT BROADCAST: [A GAVEL POUNDS DOWN] We'll hear arguments this morning in case …

[TRUMP, INC. STRINGS PLAY]

MARRITZ: On Tuesday, May 12th, the nine justices will hear arguments in a case arising from a group of lawsuits that we here at Trump, Inc. have been following closely for over a year. The lawsuits all relate to attempts to investigate the Trump family business, and to obtain Trump's tax returns.

Every step of the way, courts have ruled against Trump. Every step of the way, he's appealed. Now it's up to the Supreme Court to deliver an answer to the question: Does anyone have the power to investigate matters concerning a sitting US president?

[TRUMP, INC. THEME PLAYS]

Hello, and welcome to Trump, Inc., a podcast from ProPublica and WNYC about the business of Trump. I'm Ilya Marritz.

In the fourth year of the Trump Presidency, the chief executive is testing the limits of his power in new ways. He got to the other side of impeachment without being forced to disclose documents or allow witnesses he didn't want to be heard. Some of those who did testify were then removed from their jobs.

After Congress passed a $2 trillion coronavirus relief package, including robust, independent oversight, President Trump declared he could ignore certain provisions of the law, which said Congress must be informed about how the money is spent. And then, as if to underline that point, Trump fired an Inspector General who was set to lead oversight. He installed a White House lawyer in another key oversight job.

And there's this — to protect his business records from the time he was a private citizen and to thwart a criminal probe, Trump is asserting broad immunity from both Congressional and law enforcement investigations. His lawyers are arguing neither the United States Congress nor the Manhattan District Attorney has the right to investigate him. These cases also concern institutions like Deutsche Bank, Trump's biggest lender.

Today's show is all about a way less famous institution that is also connected — Mazars USA — which does accounting for Trump the man, and for Trump's businesses.

Trump, Inc. reporter Meg Cramer is here. Meg, how did you get interested in Mazars?

MEG CRAMER: So last year, Congress and the Manhattan DA sent out these subpoenas asking for financial information about Trump and his businesses. Congress is investigating, among other things, possible conflicts of interest, and whether or not Trump accurately reported his finances to the Office of Government Ethics. And the Manhattan DA has a criminal investigation which is related to payments to Stormy Daniels. The subpoenas went out to Deutsche Bank and Trump's outside accounting firm, Mazars USA. And right away Trump sued to block them.

MARRITZ: And Trump's argument here, in essence, is that his bankers and his accountants can't be compelled to hand over documents to investigators, so long as he's in office?

CRAMER: Exactly. And the thing is, before these subpoenas went out, I had never actually heard of Mazars, and I hadn't really given very much thought to the accountants who do Trump's taxes. So, at the beginning of the year, I knew the Supreme Court case was coming up, and I was like, “I want to figure out everything there is to know about this group of people and about their relationship with Trump.”

MARRITZ: So, tell me how you got started.

CRAMER: Well, first I went back to see, like, “Did Trump ever talk about his accountants? Did he ever mention this firm? Does their name come up anywhere?” And I want to play a piece of tape for you.

MARRITZ: Okay.

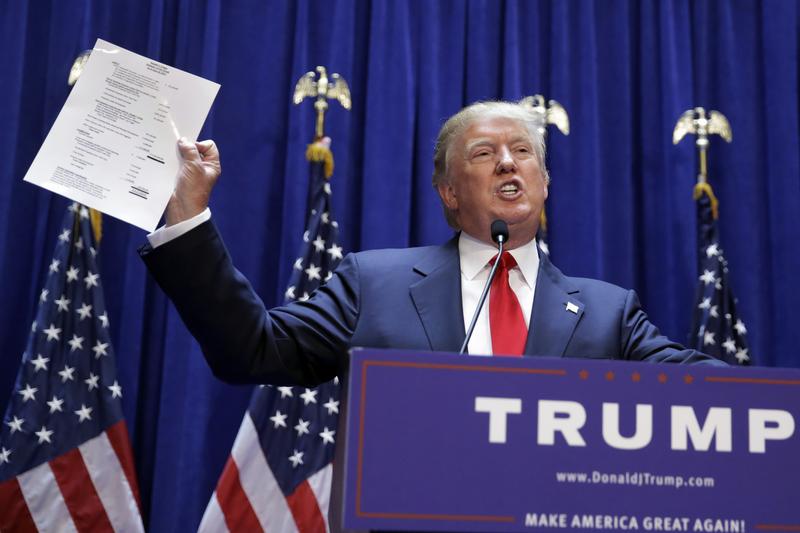

CRAMER: This is the day Trump announced he was running for president, and he actually mentioned his accounting firm that day, although not by name.

TRUMP: So a large accounting firm and my accountants have been working for months — because it's big and complex — and they've put together a statement, a financial statement.

CRAMER: So, that day, he brought this piece of paper with him. And in the video you can see that it looks like some kind of financial statement, but the words are too small to read.

TRUMP: And I have assets.

CRAMER: He holds up the paper.

TRUMP: … big accounting firm, one of the most highly respected. $9,240,000,000.

ONE PERSON FROM THE CROWD: Yeah!

TRUMP: And I have [PAUSE] liabilities.

CRAMER: So Trump said his accountants put this financial statement together. It's not actually clear whether or not that's the case. Their name is not on it, and the firm wouldn't comment when we asked.

MARRITZ: Okay, so one thing I noticed in this video is the way Donald Trump talks about his accountants. It’s as if they're the greatest accountants in the world. “They're very credentialed. Everyone knows them.” Um, are they well known?

CRAMER: Mazars USA is not particularly well-known. It's the US arm of a bigger company based in France. And Trump's accountants are part of this even smaller team within the firm. And his relationship with this small team goes way, way back — like, to when he was still a kid living in Queens.

This is the firm that was behind schemes that helped save the Trump family hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes, and the same firm that helped funnel millions of dollars to Donald Trump from his father Fred.

So I have been digging into this long relationship with another reporter, Peter Elkind, over at ProPublica. And we found that these accountants were enablers who helped Trump in these crucial moments in his career in a number of ways. And when we figured that out, we realized these subpoenas from Congress and the Manhattan DA aren't just asking for, like, clerical work from this outside accounting company that processes Trump's taxes. There is a long-term relationship here, and for the first time ever, outsiders might get a look at that relationship — depending on what the Supreme Court says.

MARRITZ: So, what else did you learn about Trump's accountants?

CRAMER: Well, we also learned that the firm has run into trouble with clients and regulators, and at one point they were operating without malpractice insurance. Also, the current CEO of Mazars was — for at least four years — barred from practicing before the Securities and Exchange Commission. In that case, the SEC found that the firm engaged in "highly unreasonable" and "improper professional conduct."

And there is another thing we found, which is a person who was there. We interviewed one of Donald Trump's accountants.

MITCHELL ZACHARY: Let me ask you this first — how did you get to me? How did you figure it out? Nobody else has ever figured it out.

CRAMER: This is Mitchell Zachary. He worked for the firm and did work for the Trump family from the late ‘80s through the early 2000s, and from about 1989 through the mid ‘90s he worked on Donald Trump's taxes. That was a while ago, but talking to Zachary opened up a window into this world we didn't know much about.

Mitchell Zachary runs an accounting firm in Florida. On the weekend he co-hosts a radio show with a local rabbi called “The Sunday Schmooze.”

[CLIP FROM “THE SUNDAY SCHMOOZE” PLAYS]

RABBI DOVID VIGLER: I want you to think about your zayde and bubbe. Do you remember building a sukkah as a child, Mitch?

ZACHARY: No, I lived in the city. We went to the shul.

RABBI VIGLER: Did you remember seeing sukkahs? Did you see other sukkahs?

ZACHARY: Yeah, of course.

[SOME CROSSTALK BEFORE THE CLIP ENDS]

CRAMER: So when I asked him if I could record our conversation, he was like, “No problem. I know how to do this.”

[‘80s MUSIC PLAYS]

CRAMER: So, should we go back to New York in the ‘80s?

ZACHARY: Sure, sure.

CRAMER: When I first called Mitchell Zachary, he told me he couldn't share confidential information about Trump's finances, but we could talk about what's already been reported on. And he could tell me, from his perspective, what it was like being Trump's accountant.

[MUSIC OUT]

ZACHARY: The first year I worked on Donald Trump's tax return — it might've been the ’88 return. And the way I did it was, I did it as if it was a company with a set of books.

CRAMER: Trump had just published The Art Of The Deal, and was spending money like he had a lot of it. This is the year he bought a hotel, refitted his yacht — the Trump Princess — and agreed to buy an airline.

ZACHARY: And I remember the first year I did it. Here, I'm working on Donald Trump's tax return, and at the end I'm like, “I'm accounting for his assets.” And there wasn't much there.

[MUSIC COMES BACK]

CRAMER: That year, he also sold shares in a casino company to the talk show host Merv Griffin.

ZACHARY: … and it was at the end of the year, and the only money he had at the end of the year was the money he got from that deal with Merv Griffin. And I went to Jack Mitnick, who was the partner in charge, and I said, “Mr. Mitnick, I — I must be missing something. There's nothing here!” And he just laughed, and went, “Well, you just figured it out.”

[MUSIC OUT]

CRAMER: The Trumps' relationship to their accounting firm goes all the way back to Fred Trump, as early as 1951. Back then, it was known as “Spahr, Lacher, and Berk.” Spahr did accounting work for Fred's business, and handled the family's taxes.

The firm was small, based in Queens, then Long Island. We couldn't find out much about the original partners. But we did find this …

ANNOUNCER: Every year, millions of Americans find themselves wondering whether or not they owe Uncle Sam any income tax and, if so, how much.

CRAMER: It’s a 21-disc set of educational records all about tax law that partners at the firm paid to produce.

ANNOUNCER: This annual effort by most people results in a frustrated gnashing of teeth. That's because the income tax law is intricate.

CRAMER: By the time this delightful series of records came out, Fred already had a close relationship with the firm. His own Chief Financial Officer came from Spahr.

When Donald Trump began building in Manhattan, he stayed with the firm. He even made the same move as Fred, hiring someone from Spahr to run accounting at the Trump Organization. The Spahr accountants continued to handle his taxes.

ZACHARY: Okay. So it's hard to imagine, but he was like, just turning 40.

[CLIP FROM DAVID LETTERMAN PLAYS. LETTERMAN: “My next guest has enough money to give everyone in the audience tonight a million dollars,” THEN CHEERING WHICH CONTINUES UNDER NARRATION]

ZACHARY: And here he was in all the press, and he had built Trump Tower, and he did the Grand Hyatt. And, you know, it was kind of exciting, you know? He was kind of glamorous.

[CLIP FROM LETTERMAN CONTINUES. TRUMP: “Most people love me, and a few really have great distaste for me.”]

CRAMER: Mitchell Zachary started working at Spahr in the late ‘80s. Soon, he was put on the Trump tax team and he took his first trip to Trump Tower.

[HI-HAT MUSIC PLAYS]

ZACHARY: It was, like, really impressive, you know? Like, I put on my best suit and my best tie, suit pants neatly pressed.

CRAMER: Right from the dry cleaner, or did you press them yourself?

ZACHARY: Uh, my wife used to help me with that. She wanted to save the dollar in dry cleaning at the time, so …

CRAMER: Donald Trump's accounting work was more technical than Fred's. Early on, they did everything by hand on sheets of green column paper. Their work on Trump's returns usually began the summer before they were due.

ZACHARY: By the time we got him the return, it was due that day. And it was boxes. It was literally boxes with all the attachments.

CRAMER: So there would be no way to read it. He wasn't reading it.

ZACHARY: No, he had this — no, he couldn't listen. He couldn't have gotten through it, even if he had more time, but he had no time.

[MUSIC OUT]

CRAMER: We learned later, from the New York Times' reporting, that by this time, Trump had begun reporting tens of millions of dollars in losses on his income taxes. Over time, the losses added up to over a billion dollars.

Most of that was other people's money — bank loans and investments into Trump's failing businesses. Even so, Trump was able use those losses to get a huge tax break. According to the Times, Trump was able to avoid paying federal income taxes for eight years between 1985 and 1994.

A lawyer for the President said the tax information in the Times' story was "demonstrably false," but cited no specific errors.

During the 2016 campaign, Trump bragged about his low tax bill.

HILLARY CLINTON: So, if he paid zero …

TRUMP: [FROM 2016] That makes me smart.

CRAMER: His campaign said it showed that he understood the tax code better than anyone who has ever run for President. In reality, it was guys like Mitchell Zachary doing all the work. I asked him if he handled any of those returns.

ZACHARY: Sure.

CRAMER: Did it seem normal to you, to be filing a return with such a big loss on it?

ZACHARY: No.

CRAMER: He says you can see from the Times reporting that Trump appears to have lost more money than anybody during that period of time.

ZACHARY: So naturally, it was very unusual.

CRAMER: He does not think Trump was pushing the envelope.

ZACHARY: Yeah, we were a little aggressive, but not, uh, pushing the envelope too far. The man lost a lot of money. We didn't need to push the envelope.

CRAMER: At one point, he put it like this: Trump had lost so much money, "he was a built-in tax shelter."

Trump was a difficult client. Zachary told me that collecting fees from Trump was awful. Eventually, Spahr negotiated a deal: Lower fees if Trump paid on time.

ZACHARY: Donald always made it clear. You get the privilege of saying you're Donald Trump's accountants, and you have to pay the price.

CRAMER: Mitchell Zachary worked under a partner at the firm, a man named Jack Mitnick. For decades, Mitnick was the accountant behind the Trump family's tax strategy. Zachary said Mitnick was known around the firm as a ‘Tax God’ — an accountant so gifted, you had to sit up and pay attention.

[HI-HAT MUSIC PLAYS]

ZACHARY: And what I learned from Jack Mitnick was keep researching until you find a way to do what you want to do. Don't give up. Just keep digging.

CRAMER: Zachary told me that Mitnick had an especially close relationship with the Trumps, that Mitnick was constantly on the phone with either Donald or Fred. He had tax ideas for them, they had questions for him — and that they wouldn't make a move without discussing it with Mitnick first.

[MUSIC OUT]

CRAMER: My conversations with Mitchell Zachary began in January, on the phone. At the very beginning of March, Peter Elkind and I flew to Florida to meet him. This was back before social distancing. Some of the tape is from our in-person interview.

[MUSIC COMES BACK]

ZACHARY: Okay. You have to understand, Jack … The — the aura around Jack Mitnick was that he was infallible. I mean, when I first came there — you might find this interesting or not — I couldn't call him Jack. I always called him Mr. Mitnick. That's part of his — his aura. You know, that he's the biggest tax expert in the world, and he's always right. And if he blesses something, you can do it. That was the feeling that everybody thought about Jack.

[MUSIC OUT]

CRAMER: He seemed to screw up again and again and again, though.

ZACHARY: Yeah. He didn't always win. His opinion wasn't always a winning position.

CRAMER: Do you think he really, like, took a lot of extreme positions?

ZACHARY: Probably. I think the court cases bear that out.

[DRIVING MUSIC COMES BACK]

PETER ELKIND: Well the first case is called Fresci vs. Grand Coal Venture.

CRAMER: This is Peter Elkind. Peter came across a federal appeals court opinion from 1985, involving Jack Mitnick and a group of investors. Mitnick was working for them, managing their investment in coal mining in North Dakota.

ELKIND: He was accused of deceiving the investors. That basically, even though he was the administrator of this operation, he told them that if this one coal mine that they were pouring their money into didn't pay off, if it wasn't productive, that he had another coal mine that would be productive and he'd guarantee that they'd turn out fine — that they'd make money.

CRAMER: Mitnick knew that was not the case. The investors accused him of fraud.

ELKIND: And after reviewing the record, both a district court — a trial court — and an appeals court concluded that that was justified. In fact, the appeals court, in a written opinion, said that the record amply demonstrates that he committed fraud, and even in the opinion said that the matter should be referred to the appropriate Professional Conduct Review Committees.

[MUSIC PLAYS FOR A MOMENT]

CRAMER: Mitnick continued working at the firm as a Senior Partner, and he continued to work closely with Fred and Donald Trump.

[BEAT]

CRAMER: The office building where Jack Mitnick and the Spahr accountants did Donald Trump's taxes for many years was this place. It's a blocky concrete structure with a sort of shabby, mid-century appeal. It's out on Long Island — a short drive from Fred Trump's home in Queens. Peter and I went there in January.

CRAMER: In the space, there’s kind of an atrium in the middle, with a central staircase going downstairs.

CRAMER: Inside, the offices have low ceilings and windowless hallways. We just went to have a look.

[ELEVATOR BEEPS]

CRAMER: It’s a squeeze to get more than two people in the elevator.

It makes sense that Fred Trump's accountants worked here. Fred himself worked out of a renovated dentist's office on Avenue Z in Brooklyn. But it's a long way from the marble and gold of Trump Tower.

Ultimately, by staying close to his father's accountants, Trump also stayed close to his father's wealth. Kind of, like, the rich-person version of staying on your family's cell phone plan.

We know now that, as Donald Trump's businesses were struggling, the Trump family accountants helped funnel millions of dollars from Fred Trump to his children.

[BEAT, THEN MUSIC SLOWLY COMES IN]

CRAMER: In 1992, the Trump Family set up a company called “All County Building Supply & Maintenance.” It was owned by Donald Trump, his siblings, and a cousin. The New York Times uncovered a number of suspect tax strategies that the Trump family used, and All County was one of them. Out of all of the schemes, The Times said All County was the "most overt fraud.” A lawyer for Trump called the Times' reporting “100% false, and highly defamatory."

I asked Mitchell Zachary about All County during our first interview.

ZACHARY: Yep. Know all about it.

CRAMER: Whose idea was that?

ZACHARY: Speci— Well, uh, it wasn't mine. I — I'll tell you that. I wish I could take credit for it — it was brilliant — but it wasn't mine.

CRAMER: Here’s how it worked. Fred Trump bought supplies for his buildings — like refrigerators, stoves, and boilers — from this company, All County Building Supply & Maintenance. All County sold Fred those supplies at hugely marked up prices.

But remember, All County was owned by Fred Trump's children, and they profited off those huge markups. The Times found that, over time, Fred was able to funnel millions of dollars to his children through All County, and could have avoided paying millions of dollars in taxes.

ZACHARY: I knew what that whole thing was about, you know. It was part of the estate planning strategy.

CRAMER: In the mid-‘90s, Mitchell Zachary left the Trump tax team, and began working on estate planning for Fred Trump.

Zachary told me that All County was implemented by the Spahr accountants, but that he wasn't part of the team that developed the strategy, and he didn't work on it directly.

ZACHARY: I wish I could take credit for it, but I only learned from it.

CRAMER: What did you learn from it?

ZACHARY: Uh, that if you plan properly [PAUSE] on a very, very large estate, then — if you have time — you could take steps to reduce the value of the properties. That was the main purpose of All County — to reduce the value of the properties for estate tax purposes.

CRAMER: A former Chief of Investigations for the Manhattan District Attorney's office, Adam Kauffmann, told the New York Times that the Trumps' use of All County would have warranted investigation for "defrauding tenants, tax fraud, and filing false documents." The statute of limitations for criminal prosecution has expired.

The Times reported on another tactic used to reduce the Trumps' tax bill: Dividing up legal ownership of Fred Trump's properties so that he lacked complete control. That helped an appraiser justify lower values, which meant lower taxes.

ZACHARY: So, at that time, uh, we brought in this appraiser and he took anywhere between 35% and 40% discount. This was a common technique we used, okay? Well, the IRS hated that.

CRAMER: After Trump's parents died, the IRS audited their estates and found they were worth 23% more than the Trump family had claimed.

All told, the Times found that Fred and Mary Trump transferred over a billion dollars of their wealth to their children — which could have meant paying over $500 million in taxes. The Trumps paid a fraction of that.

Mitchell Zachary defends the firm's work for the Trump family, saying it was aggressive but within the law. He said Donald Trump's taxes were frequently audited, and pointed out that the IRS reviewed their work on the estate taxes.

ZACHARY: Yes, it was a — maybe aggressive, some might say, but that's not — that's not unusual.

You know this, I've come across clients, Meg, that say, “I never want to get audited,” and I tell them, “I'm not your guy.” There's nothing wrong with wanting to take advantage of loopholes or, um, things that aren't specifically not allowed that — Meg, I would never sign a return where I didn't feel I could sit across from an auditor and defend my work.

[A BEAT, THEN HI-HAT MUSIC]

CRAMER: As I was reporting this story, I realized I did not fully understand what role an accountant is supposed to play when it comes to making sure their clients follow the rules.

LYNN TURNER: Yeah. So let's talk a little bit about tax schemes, tax fraud.

CRAMER: So I called up Lynn Turner. He's the former chief accountant for the Securities and Exchange Commission.

TURNER: The tax positions that, uh, a client takes are the responsibility of that client. The professional standards make it very clear that for a CPA to sign a tax return that has an aggressive tax position in it, the CPA has to have what's known as a, quote, “reasonable basis for that position,” and that it, uh, would be supportable under the tax law.

[MUSIC OUT]

CRAMER: That means there's room for interpretation.

I think a lot of us think of accountants as auditors, that their role is to double-check the numbers, and that their work is black-and-white. In many cases, though, they're working with numbers that come directly from their clients.

Lynn Turner thinks the professional standards for certified public accountants who sign tax returns are too low. He said, quote, "I think those low standards result in CPAs turning a blind eye when their clients take very risky and dangerous tax positions."

CRAMER: In 1994, Jack Mitnick got sued again. A client accused Mitnick of malpractice, and accused Mitnick and the firm of trying to cover it up.

ELKIND: They cited missed filing deadlines, false statements to the IRS — they alleged that this cost the family millions in taxes and penalties.

CRAMER: Here’s Peter Elkind again.

[INTENSE MUSIC PLAYS]

ELKIND: And one of the reasons they cited for this was, they said that Mitnick and the firm were too preoccupied with doing the Trumps' work.

CRAMER: A trial judge found that Mitnick was the primary wrongdoer in the case.

ELKIND: In that case, ultimately, the firm settled for about $500,000.

CRAMER: This was yet another time Mitnick got into serious trouble.

[MUSIC OUT]

ELKIND: I mean, accountants get sued. There are unhappy clients for an assortment of reasons. What was striking about these cases is that judges found him culpable. And it wasn't just a matter of them paying some money to make this thing go away. They paid a substantial amount of money, and courts also found that he had engaged in wrongdoing. It tells us that the guy who was masterminding the Trumps' tax schemes was, for years, operating on the edge, and, at times, clearly crossed over the line.

CRAMER: In 1996, Mitnick was ousted from the firm.

He didn't want to be interviewed for this story. Over the phone, he declined to comment on his work for the Trumps and his legal trouble.

When Mitchell Zachary became a partner in 1998, he was told the firm did not have malpractice insurance. He put his assets in his wife's name, in case the firm got sued again.

The Trump family stayed with Spahr. By then, Donald Trump's accountants were at a turning point — not just because of the malpractice insurance. The firm's senior partners were aging, its clients were aging. So, the partners began to make plans to merge with a larger firm. They checked with Donald Trump first.

ZACHARY: He was so important to us as a client for a lot of reasons. If, for whatever the reason, he said, “I have a conflict with that accounting firm. I had bad dealings with them. I don't want you to do this merger,” we would have had to walk away from the merger.

CRAMER: Confidentiality was more important with Trump than with most clients. At Spahr, the policy was: You couldn't leave Trump's documents out overnight. You had to lock them away in a cabinet.

ZACHARY: More than any other individual [BEAT] that I've ever seen, he was very big on promoting that he's this super-rich billionaire. That's not what you see when you look at his personal tax returns.

CRAMER: Donald Trump basked in the perception that he was money. In interviews with journalists, he sometimes produced papers, compiled by his accountants, which he said proved his wealth. Trump sued the journalist Tim O'Brien after O'Brien published a book claiming Trump was not a billionaire. Trump lost.

In the end, Donald Trump cared a lot about one other thing: his fees. The firm promised Trump his fees wouldn't go up after the merger, and he gave the okay. The merger went forward.

[LIGHT MUSIC PLAYS]

MARRITZ: Mitchell Zachary left the partnership in 2002. Not long after that, Trump's accounting firm faced accusations of "improper professional conduct" and "highly unreasonable conduct,” and was called in by regulators to defend its work. We'll be right back.

[MIDROLL, MUSIC OUT]

MARRITZ: And we're back. Let's just recap where we are.

One of Donald Trump's former accountants, Mitchell Zachary, has confirmed that Trump was not the super rich guy he presented himself as in The Art of the Deal. To protect that image, Trump's accountants applied a high level of secrecy and security around his finances.

Despite its big-name client, the accounting firm was still small. And the partner in charge of Trump's taxes was accused of malpractice, and was found to have committed fraud. The firm lost its malpractice insurance.

Meg picks up the story now, with Mitchell Zachary out of the picture, and Donald Trump branching out from real estate to branding and entertainment.

[THE APPRENTICE THEME SONG PLAYS IN THE BACKGROUND FOR A BEAT]

CRAMER: In January of 2004 — one week after The Apprentice premiered on NBC — the Securities and Exchange Commission formally reprimanded Donald Trump's accounting firm for willfully aiding and abetting misconduct.

Peter Elkind read through the documents, which focused on work done for another client, and the conduct of a partner named Victor Wahba.

ELKIND: Wahba had been hired to supervise a financial advisory firm that was already operating under a cease and desist order for securities fraud, so it was supposed to be under heightened scrutiny.

[DRIVER PERCUSSIVE MUSIC PLAYS]

CRAMER: The accountants' job was to make sure the financial advisory firm followed SEC rules.

ELKIND: But they failed to do their job. And the SEC concluded that they had engaged in highly unreasonable and improper professional conduct. So the sanction for Wahba was he was suspended from practicing before the SEC for at least four years.

CRAMER: In an agreed settlement, Wahba did not admit or deny wrongdoing. He declined to be interviewed for this story through a spokesperson.

In 2010, Trump's accounting firm joined a bigger firm, and eventually became Mazars USA. The accountants moved to a newer Long Island office. This one is owned by the company that makes Arizona Iced Tea. The parking lot is decorated with cactus sculptures.

Victor Wahba got a promotion.

ELKIND: In January 2012, which was just fifteen months after he was reinstated by the SEC, Wahba was named co-CEO of the entire firm, with responsibility for all its US operations. Three years after that he was named Chairman and CEO of Mazars USA, in charge of the firm all by himself.

[BEAT, MUSIC OUT]

TURNER: For that to happen -- get censured, and then prohibited from practice for four years by the SEC — is a very serious, confidence-destroying enforcement action.

CRAMER: Here’s Lynn Turner again, former chief accountant for the SEC.

TURNER: For that person to then become the CEO of a CPA firm, in my opinion, speaks loudly with respect to the confidence one would have in that firm. Better yet, the total lack of confidence one would have in that firm. And it would certainly make me wonder about the culture of that firm, and whether or not that firm acts with integrity.

[BEAT]

ELKIND: The firm wouldn't give us an interview. But they did issue a statement, saying that under Wahba's leadership Mazars has become a national leader. It defends his work and his reputation and his charitable efforts and notes that he now remains in good standing with the SEC and industry regulators.

CRAMER: When Congress requested Trump financial documents from Mazars last year, the letter was addressed to Victor Wahba, Chairman and CEO.

[HI-HAT MUSIC BACK]

CRAMER: There is another Mazars accountant mentioned in the letter from Congress, a man named Donald Bender. After Jack Mitnick was ousted from the firm, Bender took his place, as the accountant closest to Trump.

During my first interview with Zachary, over the phone, I asked him, “What did you make of Donald Bender?”

[MUSIC OUT]

ZACHARY: I don't know if that's something that I should really get into.

CRAMER: No problem.

ZACHARY: You know what I mean? Let me just say this: Donald Bender was brilliant. Very, uh, black-and-white — I'm a kind of grey accountant. So, you know, the two of us made a good combination. Personality-wise we were night and day, that’s why it's a little tricky. But I had tremendous respect for how well he knew the tax law at a time when it was very complicated.

CRAMER: Bender’s signature begins appearing on Trump's tax documents — including tax filings for the Trump Foundation. The firm audited the Foundation's financial statements for 2016 and 2017.

The following year, the New York Attorney General filed a civil suit alleging a "pattern of illegal conduct," including self-dealing, and using the charity for political purposes. Bender and the firm were not accused of wrongdoing. The Foundation agreed to dissolve, and in 2019 President Trump was ordered to pay $2 million in damages.

We reached out to the White House and the Trump Organization with questions about the President's tax strategies and his relationship to his outside accounting firm. They did not respond.

[A BEAT]

For 15 years, as Trump's businesses grew from New York real estate development into international licensing deals, Bender kept track of where Trump's money came from. He knows more than almost anyone about Trump's finances in the years leading up to his presidency — information that, so far, Trump has managed to keep private.

Bender has never spoken publicly about his work, or his relationship with Trump, and he wouldn't speak to us for this story. Of all the people involved in Trump's taxes, other than Trump himself, Bender is the person I am most curious about.

He has what so few people seem to have: a lasting, loyal relationship with Trump. After more than 30 years, it's one of the longest professional relationships Trump has ever had.

[A LONG PAUSE]

MARRITZ: Mazars USA faces huge document requests from Congress and the Manhattan District Attorney, Cy Vance Jr., for Trump's business records.

Vance is investigating potential violations of New York business law: declaring hush money as a legal expense in the Stormy Daniels affair. It is not clear what Mazars, in preparing the Trump Organization's tax filings and auditing its books, knew — or should have known — about this.

Mazars said in a statement, "Mazars USA will respect the legal process and will fully comply with its legal obligations. We believe strongly in the ethical and professional rules and regulations that govern our industry, our work, and our client interactions."

Last fall, in a Manhattan courtroom, Donald Trump's lawyers asked a panel of judges from the Second Circuit Court of Appeals to block District Attorney Cy Vance's investigation. They said Vance's probe into their client's finances was politically motivated, its basis flimsy, and that Presidents enjoy absolute immunity from state criminal proceedings while in office.

Judge Denny Chin asked, “Does that principle apply even when the possible crime being investigated is plain for anyone to see?” He picked a hypothetical — raised by Trump himself during the 2016 campaign.

TRUMP: [IN THE CAMPAIGN] I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn't lose any voters, okay? It’s, like, incredible. [CROWD CHEERS]

JUDGE DENNY CHIN: What's your view on the Fifth Avenue example?

CRAMER: Judge Chin.

JUDGE CHIN: Local authorities couldn't investigate? They couldn't do anything about it?

CRAMER: Trump attorney William Consovoy gave the answer.

ATTORNEY WILLIAM CONSOVOY: I — I — I think once the — a President is removed from office, any local authority … This is not a permanent immunity.

JUDGE CHIN: Well, I'm talking about while in office.

CONSOVOY: No.

JUDGE CHIN: That’s the hypo.

CONSOVOY: There — I …

JUDGE CHIN: Nothing could be done? That is your position?

CONSOVOY: That is correct.

[SERIOUS PIANO MUSIC PLAYS]

CRAMER: The appeals panel rejected that argument. They noted that the Supreme Court in 1974 ruled against another President trying to draw a line around his records. In that case, it was President Richard Nixon's taped conversations with advisors. The decision was unanimous.

[A BEAT]

On May 12, the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in Trump v. Mazars USA, LLP, and Trump v. Vance. Their decision, or decisions, could redefine the limits of Presidential power, for decades to come. We'll be back with a new episode soon after oral arguments.

[MUSIC PLAYS FOR A MOMENT, THEN SLOWLY PLAYS OUT]

CRAMER: This episode was reported by Meg Cramer and Peter Elkind with Doris Burke. Production help from Katherine Sullivan and Alice Wilder. It was edited by Nick Varchaver, Eric Umansky, and Andrea Bernstein. Jared Paul does our sound design and original scoring. Hannis Brown wrote our theme and additional music. Special thanks to Heather Vogell, Kyle Welch, and the National Archives at New York City. Also thanks to Jalen Hutchinson, the University of Alabama Libraries, and New York Public Radio's Director of Archives Andy Lanset.

Matt Collette is the Executive Producer of Trump, Inc. Emily Botein is the Vice President for Original Programming at WNYC and Stephen Engelberg is the Editor-in-Chief of ProPublica.

I'm Ilya Marritz. Thank you for listening.

[PIANO-DRIVEN MUSIC COMES BACK AND PLAYS OUT]

Copyright © 2020 ProPublica and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.