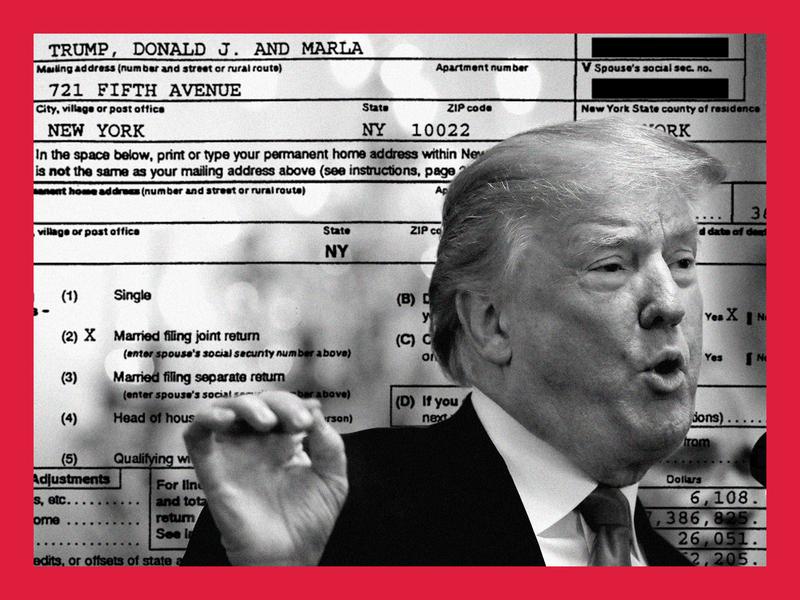

What We’ve Learned From Trump’s Tax Transcripts

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: Hey! How are you?

SUSANNE CRAIG: Good!

BERNSTEIN: So nice to see you! Great job!

CRAIG: Thank you!

[TRUMP, INC. THEME STRINGS PLAY]

BERNSTEIN: This is Susanne Craig, of The New York Times.

BERNSTEIN: Okay. I spoke to you, like, twice in the last two weeks and nothing — no hint. [BOTH LAUGH]

BERNSTEIN: Sue, with her colleague Russ Buettner, just did another story in their blockbuster series based on Donald Trump and his father Fred Trump's tax returns. This one showed how Trump claimed over a billion dollars in business losses from 1985 to 1994. That means he claimed more money losses, beginning even earlier in his career, than we previously realized. Also, Sue and Russ found, in some years Trump lost more money than any American taxpayer. In 1990 and 1991, he claimed he lost $250 million — more than twice the amount of the taxpayers who lost the second biggest amounts.

[TRUMP, INC. THEME PLAYS]

BERNSTEIN: Hello, and welcome to this Trump, Inc. podcast extra. I'm Andrea Bernstein. We thought you'd like to hear from Susanne Craig about how she got the story and what she found, so producer Katherine Sullivan and I took the subway up to The New York Times for a chat in one of their conference rooms.

We start with a bit of backstory about Sue's reporting on a 1995 tax return she received in a brown envelope during the presidential campaign.

[THEME OUT]

CRAIG: In 2016, within the last weeks of the campaign, I was mailed three pages of Donald Trump's tax returns, and that showed that he had a net operating loss that year of almost a billion dollars. It was stunning. It represented, like, a percentage point or plus of all the operating losses in the country that year — it was that large.

BERNSTEIN: So how does this new information that you have alter our understanding of how Trump has done business?

SUE: What we can see now is how that built. And if you would have asked me in the final days of the campaign in 2016, when I first got that, I would have said a lot of that came from the casino wreckage. And now we understand it came from years starting in 1984 as well, and it started well before the point where he has publicly said he was in distress.

[BACKGROUND MUSIC PLAYS]

BERNSTEIN: Were you surprised by the ways he accrued the losses?

SC: I have to say, as a reporter who's covered Trump for quite awhile now who’s pretty familiar with his finances, I would have picked the year in there — maybe two years — that he made some money. Maybe the year he wrote Art of the Deal in 1987. And it turns out that year he had core business losses were $42+ million. There's just never been a year that we can see in this period that he has — that he's made money. That's pretty incredible to think that that's the case, especially those early years. The narrative that he has created is that it was really 1990 where he crashed. His casinos went bankrupt. That was sort of the lowest point in his life financially. It turns out that the tides turned for him financially much earlier than previously known.

[MUSIC OUT]

BERNSTEIN: One of the things that is so striking to me about your story today is it shows how the business is the business. Which is to say, like, what ways can he try to make money?

CRAIG: His business model is sort of ever-shifting — kind of almost, you know, depends who calls him that day and what he gets involved in. I mean it's shifted from marketing golf courses, to real estate, to ventures like Trump University. There's just a lot going on. And you see some of this shifting going on with the numbers that we have.

BERNSTEIN: I — I think that the public perception is, “Okay. He was a real estate [A BREATH] guy and then he did The Apprentice and he did some licensing of things.” But there's such a variety of attempted money-making schemes that come out through these tax returns.

CRAIG: Yeah, I think that — yeah, he tries something. It works, it doesn't work, and he moves on to the next thing. And I think you start to see that and get a feel for that in the numbers that we have. We even see, you know, there's book royalties that show up in 1987 when he did Art of the Deal and we can see how much that was bringing in, and then in 1990 I think there was a board game, and you see that. But the — the losses are just staggering in there. Donald Trump has his often said to us — and he said it again in a Tweet after the story came out — that this is all depreciation and just, you know … Real estate guys get great tax breaks. I mean, there's some of that in there, but what we're seeing is not that. What we're seeing is a guy who ran businesses that — that were horrible. The depreciation accounts for a small fraction of it. You can't come up with a billion-plus dollars and core business losses simply through depreciation. I mean, he bankrupted companies and he lost money on other ventures. And that's the vast majority of what we're seeing.

[MUSICAL FLOURISH]

BERNSTEIN: His defense writ large is, this is normal, the way real estate works, and you — if you understood real estate, you'd never say this is normal. What does reporting tell you about that?

SC: Well, if it's normal, there would be other taxpayers of his ilk that have losses like this, and nobody does in the country. It's not normal. I mean, you can even look at his father's taxes — which we have! And Fred Trump [CHUCKLING] does not have tax returns that look like Donald Trump's tax returns. You don't lose this much money unless you're a really bad businessman.

BERNSTEIN: It is a striking — striking generational difference. I mean, because it's not necessarily the trajectory of New York real estate families, which is — they’re very dynastic. But the second generation doesn't always lose a lot of money.

CRAIG: Donald Trump didn't want to stay in Brooklyn and Queens and be a property manager. And so he decided to go his own way and came into Manhattan, and then just became his own person and sort of getting involved in all these different things. He never had to worry about money because, you know, whatever bet he was placing, Fred Trump pretty much had it covered in one way or another. So he just started branching out and all these different ventures.

BERNSTEIN: Is he rich?

CRAIG: How do you define “rich”? That’s, uh …

BERNSTEIN: It's one of the things is — he seems like he's rich. He acts like a very wealthy man. And, well, you touched on your story about how he makes other people take the losses that he —

SC: I think it's interesting because you say, you know, “Is he rich?” He has portrayed himself to be a self-made billionaire, and he's not. I mean, I sort of look more at the myth-making of that and, you know, he had a bit of a “Fake It Till You Make It” thing, and we saw that starting out with his father. And, you know, when he was growing up, he started working for his father. And, he — you know, famously, there's a 1976 article that The New York Times ran where he's telling the New York Times reporter he's worth $200 million. He starts showing the reporter all of his buildings and his jobs, and “I own this and that,” and pretty much everything that he took the reporter around in his limousine — which actually was his father’s — was his father's. He started out by appropriating his father's wealth and then he continued with that and he has been spinning this myth for a long time.

BERNSTEIN: This story that you referred to was just the one where the lead has to do with Robert Redford?

CRAIG: Yes.

AB: And it says he looks ever so much like Robert Redford?

CRAIG: Yeah, yeah. It says, “He's tall and lean and blond and worth 200 million dollars.” He says. [LAUGHS]

[MUSICAL FLOURISH]

BERNSTEIN: How did you — how did you piece the story together?

CRAIG: Yeah, yeah. Sure. No, it took us a while. We — we obtained a transcript an IRS transcript of 10 years of his taxes, and that is pretty much every number that flows onto the main tax forms called the 1040. And with that I could piece together, you know — I filled out a couple tax returns just so I could look at them, sort of hard copy. So we had that. And tax returns are incredibly difficult [EXHALE] to verify. So in this case we had the transcript. We asked the source who provided us with the transcript to provide us with a transcript of Fred Trump's tax returns. We're fortunate enough that we have a number of years of Fred Trump's tax returns, so we were able to verify that the transcript at least — the information that he'd given us on Fred Trump — was dollar-for-dollar accurate. And then we used a database that the IRS compiles and we were able to both look and contextualize Trump's taxes within that but also find his tax information in this anonymous database because we already had his taxes. So we were able to verify it through that.

BERNSTEIN: Must've been quite shocking to find out that his numbers were at the top of the losses.

CRAIG: I mean, it was, because you, sort of — you don’t see very many people's taxes in terms of businessmen and how they're doing, and to see that somebody you know that his losses — just year after year after year — were, you know, among the highest in America of individual taxpayers is pretty incredible.

BERNSTEIN: There’s a picture that he Tweeted of himself sitting next to this three foot-tall stack of tax returns. If you had that three foot-tall stack, what would you look at first?

CRAIG: I would look at his sources of income.

[MUSICAL MOMENT]

BERNSTEIN: And with what specificity will we know?

CRAIG: It depends on many of those returns we got. But you still have, you know, anything that he's told Uncle Sam in terms of the sources of income you're going to see it. I mean, you've got to start stretching back into his schedules of his different companies and stuff. But yeah. You'll get a pretty good view into it.

[MUSIC OUT]

BERNSTEIN: What does this tell us about what we should be looking for specifically now, if we ever get a look at his more recent tax returns?

CRAIG: I think you're going to understand how his businesses are doing, how well they're doing — or not. Tax returns don't answer the question of wealth, but you can get a sense of how much money somebody has and how much they're making through their tax returns. And I think that he doesn't want us to see that if he's not as successful financially as he has said he is. And we're seeing in, you know, at least tax information that we have now that he's a pretty bad businessman. So that could bear out in his modern tax returns. And you also see just his business mix. I mean, his golf courses — golf courses are a pretty tough business, how are they doing? Stuff like that. I mean, it'll be interesting. I think eventually they're going to come out in some form or the other. So we'll see. I don't know if we're gonna get every schedule though, but I think fragments will continue to leak out and this is going to be, you know, the next couple years.

BERNSTEIN: So, of this $1.17 billion, a lot of it — the majority — do we know? — was other people's money?

CRAIG: I would say it was probably the majority. I don't have a breakdown. We just don't have a breakdown of it, but a lot of it was other people's money.

BERNSTEIN: So he can take it as a loss on his tax return. He could take the whole thing, even though other people have given him the money, and he's actually losing other people's money.

CRAIG: It's incredible to think you can lose other people's money and then use it to shelter taxable income going forward for yourself. But that's the way it works.

BERNSTEIN: So, it’s kind of like if I'm a gambler and I borrow the money for you and, like, you only win if — if I win, [BOTH LAUGH] and I lose all the money, and I'm like, “Sorry.”

CRAIG: Well, there's a reason why the banks — most of them don't like Donald Trump.

[MUSIC CUE IN]

BERNSTEIN: I have a question from Ilya. Just really explain this for me. How is it possible to lose so much money and still be in business and still be rich?

CRAIG: I — I mean, his companies filed for bankruptcy, and he just kept going. So it's just it's the wonder of America I guess. Yeah.

BERNSTEIN: Susanne Craig of The New York Times. When The Times asked Trump officials about their findings, a spokesperson initially told them that, ”You can make a large income and not have to pay a large amount of taxes." Later, Trump's lawyer Charles J. Harder wrote that The New York Times tax information was "demonstrably false." He cited no specific errors.

Until 2016 Americans were used to getting tax returns from presidential candidates. These hints from Trump's earlier years underscore what's lost when that norm breaks down — and why Congressional Democrats and the New York Legislature are trying to have a look at the President's tax returns.

Remember, Sue isn't the only who likes to get brown envelopes with information. To find out how to send us tips, go to TrumpIncPodcast.org.

[MUSIC TRANSITIONS INTO CREDITS MUSIC]

BERNSTEIN: This Trump, Inc. podcast extra was produced by Katherine Sullivan and Meg Cramer. The technical director is Bill Moss. The editors are Charlie Herman and Eric Umansky. Jim Schachter is the Vice President for News at WNYC and Steve Engleberg is the Editor-in-Chief at ProPublica. The original music is by Hannis Brown.

[MUSIC OUT]

BERNSTEIN: So, I — I understand that you have, like, a secret document room with all the tax returns.

CRAIG: We did for the — for the project in 2000. Yeah. Last year. We don't anymore.

BERNSTEIN: You dismantled the room?

CRAIG: Yeah. Yeah, we did.

BERNSTEIN: Well, what’d you do for this one? You have another room?

CRAIG: No, no. We just sat at our desks. And, uh — we didn’t have quite as many documents. Yeah.

BERNSTEIN: I see. How — how many —

CRAIG: We were — we were in the hundreds of thousands for that one. For this one, just a few.

BERNSTEIN: So it wasn’t, like, feet tall. Wow. Did you read all those hundreds of thousands of pages? [LAUGHS LIGHTLY]

CRAIG: Yeah. We did. That's why it took us 18 months. [LAUGHS]

BERNSTEIN: Did you personally read them?

CRAIG: Yeah. The three of us did. Yeah. Just the three of us.

Copyright © 2019 ProPublica and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.