The Writer Dmitry Bykov on Putin’s Russia, the Land of the “Most Free Slaves”

[music]

Speaker 1: Listener-supported WNYC studios.

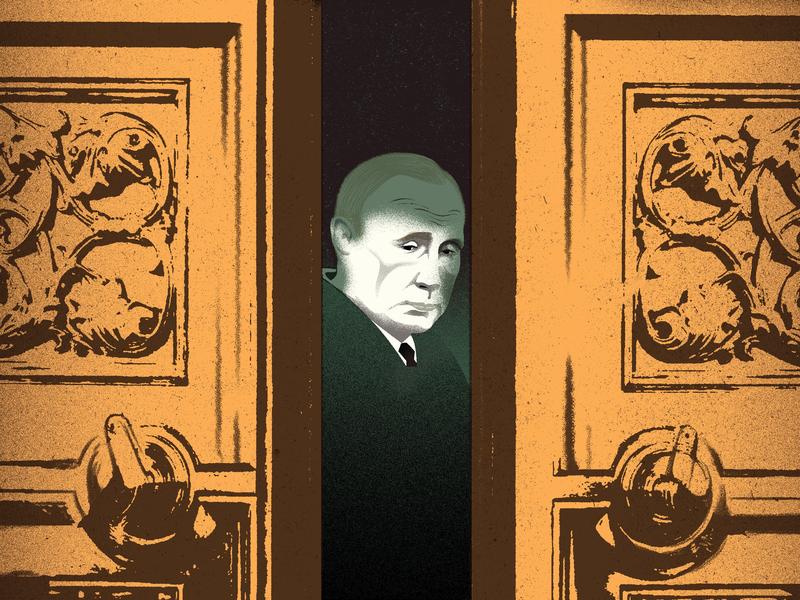

Interviewer: Until very recently, Dmitry Bykov was a big presence on the Russian literary scene. He's a novelist, a poet, a biographer, and a critic. He's also one of the most outspoken and brilliant critics of Russian life and politics. He was a frequent presence on Echo of Moscow, the liberal radio station that was finally shut down after the invasion of Ukraine. As a commentator, he pronounced scathing judgements, truly scathing on the nature and character of Vladimir Putin and the increasingly authoritarian regime he was building, and that never endeared him to those in power.

In recent years, Bykov has been teaching on and off in the United States at Cornell University, but because of his forthright opposition to the war in Ukraine, it's not at all clear that he'll ever return home. You were just in Ukraine, tell me about the circumstances of the trip and what you saw.

Dmitry Bykov: You can only feel it, that's really strange feeling of people who live after death. They have decided for them on the 23rd of February, the dead death, that everything is lost and now they're quite free. That's like Japanese school of Samurai. Imagine that you are dead and then act, you are living after death. Everything is finished, so feel yourself free and decisive. They are free and decisive. It's the carnival after death. It's very merry and very horrifying. The people who really decided to die for their country because they have no exit. They really feel the firm wall behind them.

Interviewer: That is no exit.

Dmitry Bykov: Yes, no exit and no place to run. Most of men before 60 just are forbidden to leave the country. By the way, there was so long lines to get arms to join the so-called territorial defense. You never could imagine such an active population, especially to compare them with Russian population, which prefers to spend its time in restaurants as if nothing happened. All Ukraine is mobilized and all the Ukraine is a kind of plasma which is ready for transformation in something unpredictable and maybe unimaginable.

Interviewer: Tell me how you received the news that Russia under Putin was invading Ukraine. Did it take you by surprise, or was this just an extension of what began in 2014?

Dmitry Bykov: I really complicate the problem because I was waiting for the war for a recent 20 years. I was predicting it in most of my books. For example, one of my books is just called The Chronicle of The Nearest War. I was ready for it, but I was sure that war between Russia and Ukraine would be delayed somehow and I was waiting for it maybe next year. Now, I came to continue my work in America after the winter vacations in the middle of February, by the way, just after my visit to Kiev. Then when I appeared here a week later, the war began.

Interviewer: It's hard to explain to people who have never been there, but for the past decades, people who were in your milia; writers, journalists, and then also business people and all kinds of people lived a double life, to say the least, in Moscow, which is to say it was distinctly post-Soviet, certain things existed that had never existed before. If I walked into a bookshop in Moscow or Petersburg or anywhere else, I could find books by Dmitry Bykov and many, many others that would never have been there in the certainly late Soviet period.

There were restaurants and there was a social life and a commercial life that had exploded, but at the same time, Putinism existed. Describe for us, for an American, what that deceptive semi-authoritarian, semi-democratic culture was before the war in Ukraine?

Dmitry Bykov: As for me, there was practically nothing. The dictatorship wasn't even in Russia, you couldn't feel it, for example. My books were not forbidden till March and you could buy them, but as for the position, they were always feeling the pressure. For example, I was banned as a teacher, as a lecturer. I couldn't, for example, teach in official university, only private schools. I had right to had the license to read lectures, for example, for adults, not for children, but only my private Victorian, The Straight Speech. I wasn't allowed as an official teacher. Then most of Russian oppositioners were always checked for their financial documents and for their non-extremism.

You know that extremism is a typical verdict for Russian oppositioners. The restaurants are open, so the life is normal. You see one of my friends said they go to restaurants because they have no other business, everything except restaurant is forbidden. Maybe the dictatorship wasn't evident for foreign guests and for Russian Philistines who waste their time in restaurants. There is no journalism, there is no normal business, only business which is allowed by the state, and so on. By the way, in one of Vasil Bykaŭ's novels, The Sign of Drama, The Sign of Trauma, he wrote, "My only freedom is to smoke because when I smoke, maybe that's the sign of free will."

For everybody who could see it in things, it was quite clear that dictatorship is not only near, dictatorship is here and we understood it. You felt being a poet, being a writer, being too sensitive maybe to be happy, you were feeling the horrifying pressure, which was strengthening all the time. Sometimes you could feel exceptionally being drunk. You could feel that this is your motherland and you are at home, but most of the time, I felt myself being at home in an American bookstore.

Interviewer: You felt most at home being in an American bookstore, did you feel that way in the early '90s and the first flush of the Post-Soviet period? How long did it take before it became evident that any glimmer of a democratic possibility in Russia was over?

Dmitry Bykov: You see only naive Americans could believe in democratic possibilities in '90s. I lived there and I could see it. There were no democracy, there was a new dictatorship, and so Yeltsin wasn't a Democrat at all. He tried to be Democrat, but he was a typical party leader who always creates external situations because he can act only in such situations, not in a peaceful world. As for me, I was quite sure, even in the end of '80s and I was writing about it in my young and non-experienced journalism, in the end of '80s, I was writing much. Then the destroying of the Soviet Union was an attempt to destroy a complicated system.

Maybe the complication of system is their only measure of freedom. The Soviet Union was not as simple and straight as it is described, for example, abroad or in the novels of Russian dissidents. There were many types of people and many types of communities in Soviet Russia. '90s were the decay of degradation, of the decay in all spheres of life, in culture and science, in social sciences, and so on. There were some perspectives for the Soviet Union. Like, for example, in a complicated chess part in chess game, but all the figures were thrown away from the board and that's the reason.

Interviewer: All the pieces were swept off the board.

Dmitry Bykov: Yes, and that's the reason that the Soviet Union was not transformed. It was not transformed. It could be transformed, sure but it wasn't.

Interviewer: What meaning does Putin therefore have? Was Putin a logical continuation of the Yeltsin you described from the '90s?

Dmitry Bykov: I must say that indeed Putin seems to be a real full over Yeltsin because Yeltsin's way of decision of salvation of our problems was to shoot like in Chechnya, for example, and in 1993. Soviet Minister of Defense [unintelligible 00:10:46] said that we can take Grozny for three hours. Russia maybe was killing its soldiers there for 10 years. They were sure that they'll take Kiev for three days. Now we understand that Ukraine appeared the giant swamp for Russian militaries and maybe this war is for years. They can't take even Lisichansk.

I think that Putin is just the final stage of Russian decline because he's maybe the simplest, the most primitive figure in Russian power. He's so much smaller than the country. Not only because he's small in general, but because his figure is comically and finally little.

Interviewer: Why do you say that? For years, much of the foreign press would talk about Putin as a master strategist as far more experienced in the ways of power in the Machiavellian sense than anyone else on the world stage. You're describing him as a pipsqueak.

Dmitry Bykov: Not a pipsqueak but a really primitive figure.

Interviewer: How do you mean?

Dmitry Bykov: You see, it's very simple to be a strategist in Russia. When the patience of people is endless and when you can do practically everything with them, including, for example, public executions, maybe there's the limit of their power, you can do everything. Maybe this strategy is right. This strategy is not wrong because Vyacheslav Volodin, the speaker of Russian parliament, said there would be no rush with output. Maybe he's right because in Russia, Putin is the only and the last version of Russians are. After him, there would be no legal governor of Russia.

He's the last person who can unite the country somehow. In Russia, they have just very clear choice to change the country, to change themselves, or to keep Putin. They prefer to keep Putin.

[laughter]

They're really ready to die, but not to change their mind.

Interviewer: You seem to say it's impossible for anyone to imagine a Russia after Putin, Putin is a mortal figure. Can you imagine Russia politically after Putin?

Dmitry Bykov: As for me, I can imagine, first of all, federal Russia. Russia will sell government with regions which can govern themselves without directions of the center, but in Russia, most of people will oppose you. They will say, "You call to the destroy of the system, you want to destroy the system." Most of them will run away from the central. I am sure that the only way to keep Russia as the whole Russia, as in Russia, as integrity, is to give all the rights to the government in places, for example, in cities, in republics and so on.

To make something like the United States of Russia, but in Russia, this idea is not popular because everybody believes only in centralization, only in central power and pyramid of power in the so-called vertical. I'm sure that after Putin, we wouldn't keep the vertical system of power, but most of people are sure that in paternalist, or maternalist state like Russia, nobody can be free because when you take decisions like voting, for example, you are responsible for it. Most of Russian population wants to make Putin responsible for everything. To say after him, "We didn't know, we couldn't prevent him." This system, this run away from responsibility is very comfortable for life.

Interviewer: Dmitry, you seem to hold the view that Americans mainly never permit themselves, which is to think of something as fixed and unchangeable. You seem to have the view that Russia is eternally doomed to some form of totalitarianism or authoritarianism and to have a faith that we'll never see it free.

Dmitry Bykov: By the way, it's not maybe a totalitarian power, it's some strange type of freedom. I'll explain. One of my students gave me a universal answer. I asked them in one of the groups teaching post-Soviet Russia, "How can you describe the system where nobody believes in totalitarian ideas, where everybody are joking about it and laughing at it, but nevertheless, they're obedient? Is it the country of slaves or the country of free people who are really free deep in their hearts?" One of my students said, "In Russia, slavery and freedom are not mutually exclusive."

That's quite right. Maybe we're the country of most free slaves, most obedient, and maybe sometimes most quiet, but deep in their heart, they never believe to the words they see. It means that real, true fascism in Russia is not possible because fascism is a type of intellectual discipline, but there is an imitative fascism. Most of the country is really serving Putin without any deep belief in his abilities or ideas. I'm quite sure that in Russia, there are maybe 5% who really hate Ukrainians for their idea of freedom and maybe 5% are liberals and 90% are just waiting for any unseen future, any unpredictable future.

Interviewer: Dmitry, do you have family and friends in Ukraine?

Dmitry Bykov: I have family only in Haisyn. My ex-family, for example, my oldest son lives in Russia. That's a strange thing, really, but, for example, during the night, I will come as a guest to most of my Ukrainian friends, they'll be happy to see me. I can't say it about my Russian friends, they wouldn't be happy. Not only because maybe they're Putinists, no, maybe sometimes they are my followers still, but in Russia, people are not happy when they see a night guest. They are afraid of him. Generally, maybe I found Ukraine about 100 or 200 close friends, really intimate friends, and in Russia, maybe 10 people.

Interviewer: Really? Only 10 friends in Russia?

Dmitry Bykov: Only 10, yes. Sometimes I feel a kind of nostalgia, and I want to call something just to call and to talk, but most of those people are dead, I'm old enough, and some of them changed radically and I can't recognize them, and only 10 of them would be glad to hear me.

Interviewer: You and I were emailing, and I asked you, do you think that you have seen Russia for the last time?

Dmitry Bykov: It's a national sport in Russia to imagine that you see everything for the last time. When I left Russia half a year ago, I was quite sure that I'll be back, and even now, I'm quite sure that I'll be back very soon. I'm sure that we'll meet the New Year as usual at Moscow, which is banned now. The same building at [unintelligible 00:19:18], we'll celebrate the New Year.

Interviewer: Whoa, whoa, whoa, wait, what you're saying is, by the end of the year, not only will you be back in Moscow--

Dmitry Bykov: Yes, by the end of the year because we'll have the radical change in August and the disappearance of Putin's regime in October. That's not only my prediction, I have a very professional predictor in Russia who agrees with me.

Interviewer: Who is that?

Dmitry Bykov: Just a girl from my class. I have talked with my friends, most of sensitive friends feel the nearing of catastrophe.

Interviewer: The catastrophe would be what?

Dmitry Bykov: I can't say, maybe it would be a typical Russian evolution, senseless as Pushkin said, and cruel. Putin's ideas are not very popular among his surroundings. I can't imagine how it happens. I only see the direction. Maybe I give 10% or 15% for peaceful development of this situation, but every of his step is worse, for example, than yesterday.

Interviewer: Dmitry Bykov, thank you so much for your time.

Dmitry Bykov: Thank you so much. Bye.

[music]

Interviewer: Dmitry Bykov, novelist, poet, biographer, journalist, and broadcaster, and now a man without a country. He's currently teaching in the US at the Institute for European Studies based at Cornell University.

Speaker 2: WNYC Studios is supported by the Guggenheim Museum pleased to welcome Taylor Johnson as its first poet in residence. Under the theme Temple of Spirit, Johnson

presents a suite of programs engaging the museum's architecture, exhibitions, and collection. Visitors of all ages are invited to pop up reading's talks and to interact with poetry and visual art throughout the museum and online. Register at guggenheim.org/poetry.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.