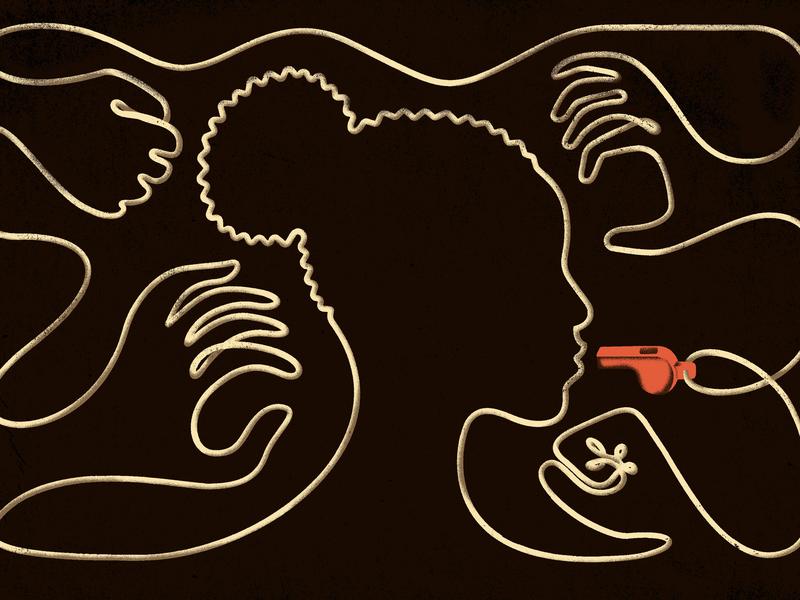

The Trials of a Whistle-blower

David Remnick: When we hear from a whistleblower, it often sets off frenetic news cycles. Think of the recent Facebook revelations first in the Wall Street Journal and then absolutely everywhere. Whistleblowers are insiders, and without them many abuses would never come to light. Often enough they're celebrated for a while for their bravery and then the story recedes. For those people who are brave enough to blow the whistle, the repercussions don't end with the news cycle. Sarah Stillman covers immigration for The New Yorker and she has this story.

Sarah Stillman: If you were paying attention to the news back in September of 2020, you probably heard about the really chilling allegations of medical mistreatment at the Irwin County Detention Center, which is a for-profit detention facility in Georgia.

News Anchor: Breaking news today, it's about an alarming new whistleblower complaint that alleges, "high numbers of female detainees, detained immigrants and an ICE detention center in Georgia received questionable hysterectomies while in ICE custody".

Sarah: Women were describing having experienced forced hysterectomies, heinous medical neglect in the midst of the pandemic.

News Anchor: Are failing to protect both prisoners and employees from the virus.

Sarah: One of the central faces you may have seen is the face of a woman named Dawn Wooten, who was a nurse at the facility where all of this was happening. She, along with a bunch of the women who had these experiences in detention, she spoke up about the really chilling things that she was seeing and experiencing. Recently, I got a call after all this time had passed from Dawn Wooten's attorney and she said so many people followed that story in the news, it sparked congressional investigations. It sparked a civil lawsuit and criminal investigation about all the misconduct that Dawn had helped to reveal, but what very few people know is what happened to Dawn after she blew the whistle on this.

Dawn Wooten: See the way I was sitting down [inaudible 00:01:59]

Sarah: Dawn is a mother of five kids and she lives in a small town about three hours from Atlanta in Tifton, Georgia.

Ms. Wooten: They're decorations. This year was rough, this year this whistle-blowing is rough. We decorated, I really was not Christmas spirited, but the kids were already and put things out. I told them, I said, "Get something in working motion then we can have a Christmas in July, maybe."

Speaker 2: What kept them from doing the Christmas just [inaudible 00:02:38]

Ms. Wooten: Finances. We were not [inaudible 00:02:42]

Sarah: There's not a lot of them for information about what whistleblowers go through after they come forward. Particularly for those who are low-wage workers, I think oftentimes the whistleblowers that we see who have made such a difference in our society, people like recently the Facebook employees who came forward or people who've come forward to reveal things happening at the upper echelons of the US government. We don't think as much about what is the cost of coming forward for those who have at a more precarious end of the economic spectrum? What are the emotional, but also even the basic financial effects on their ability to who get by?

Ms. Wooten: To be actually asked where am I? How am I faring? Means the world at this moment to us. I'm going to include the babies too because we've been on a topsy-turvy, downward spiral around the mountain world. It's like fruit basket turnover. I'm grateful, I'm grateful for the opportunity.

Sarah: I'm curious, like if you were talking to someone who you didn't know at that time and who was asking you what is your job? How would you have described your job to someone who knew nothing about the immigration detention context at that time?

Ms. Wooten: Describing the actual place that I worked at was not fit for my pet Chihuahua that I don't own and I'm being facetious when I say this and very sarcastic. It was more of a place of a kennel or I would say a animal shelter. It was not clean to the point they did not have adequate at times, adequate water there. It was not adequate for them. The food, I have seen maggots in the food.

Sarah: Oh my God. As appalling as that is to hear, Dawn started to learn things that she found even more disturbing.

Ms. Wooten: I have this young lady that I can see her, Sarah, to this day, I can call her name. We had a conversation because we always had conversations talking about her family and her kids and her children and when she gets out of here. She comes to me and she said, "Ms. Wooten, can you see what procedure I've had?" I brought back, "Hey, you've had a hysterectomy?" Other ladies, "Hey, you've had your tubes removed." "Hey, you've had your ovaries." "Hey, you've had a D&C." "Your uterus has been thinned." "Hey, you've had this surgical procedure."

In the midst of talking to these ladies from one person to 12, 12 to 24 requests at this time, I walked over to the pharmacy and I'm sitting at my car and I'm going, "What in the world is going on here? What in the hell did I walk into?" After I go through all of those emotions, Sarah, it's like I'm coming home one day in my truck and my eyes are full of water and I'm like, "Okay, God, what do you want me to do? You've got a sense of humor, this is not funny. What do you want me to do?" I'm 20 minutes home, I pull in my driveway and I sit and I was like, "Now I understand the assignment.

You want me to speak for those." Because my grandma told me that this model's going to write a check one day so big my blood couldn't cash so we always joked about it. It's like, "Now I see what it is." Now I get to work, I come back and I'm asking questions like my supervisor, "Oh, you going to leave that alone?" "Oh, you don't want to touch that." "Oh, you don't want to bother that." "Oh, you don't want to talk about that." Now I'm getting that type of treatment now coming through. I'm like, "It's got to be something that's going on here." Now I've turned in from LPN to Inch High, Private Eye because I just can't let this go.

Sarah: Do you remember what was the moment when you realized you were being retaliated against at work?

Ms. Wooten: The moment I realized I was being retaliated on when I was written up and I hadn't been written up out of the 12 years I had been nursing or I hadn't been written up out of the three cycles I had been through that place. I automatically knew that they were building a case with this write-up because I didn't have a write-up on my file. When she wrote me up bogusly for no call, no show, I've never been on no call, no show.

When I had the conversation with the deputy warden, he said, "Dawn, just take it. It's just a write-up. That's all you have to do." I said, "But it's a lie. It's not the truth." I have a doctor's excuse for the day, she's proclaiming that I was a no-call, no-show. I went outside of my car, came back with the doctor's excuse for the time, "Well, you might want to take this to the warden." I asked him, I said, "What is going on? I've never been written up. I've never had a problem in this place. You've never had any issues with me." He said he'll call me when he need me.

Sarah: Suddenly Dawn just stops getting work. They demoted her from full-time status to an as-needed employee and then essentially they just never call. Dawn's really struggling with that. She's floundering about what to do and then at that point she hears about this grassroots advocacy organization called Project South. They have been looking into these conditions at the detention center for years. They've been talking to many, many women who've been directly affected by it and organizing around it, and then together with a bunch of other groups, they all decide to fight a complaint with the Department of Homeland Security at the office of the Inspector General.

Dawn also files a separate whistleblower complaint. Those land in September of 2020, The Intercept picks it up, a small legal blog does too in an even more sensational way and suddenly the story just goes viral on social media. Suddenly Dawn is making appearances on the national news networks on Rachel Maddow, she's on Chris Hayes.

Chris Hayes: Ms. Wooten, I want to start with you and just ask you to tell us what you did. What was your job at this facility? When did you start working there?

Ms. Wooten: I was first employee at Irwin County Detention Center in 2010, I've been to this facility. It just exploded, September 14th, I'll never forget 2020. You can find me now on Google. You never could type my name in, but you can type my name in. This thing became live and I'm still brain fogged at this time like, "What is a whistleblower?" "What did I just do?" Never thought that I would wake up every day for a certain period of time and have to hear it and hear it and hear it and hear it and hear it and hear it. I never thought that it would be to this degree. I was everywhere. My emotions were everywhere. I was depressed.

I should have been excited

I had done a good thing. I'm angry and I'm fearful at the same time. If doing a good thing costs me my job and doing a thing cost me now my life. Now I also have people on the reverse end that want my throat. Now I'm messing with the commodity in a small hick town city that they make their money is the biggest industrial part of them flourishing in the city, now I'm messing with that economically. Now I don't know who wants my head on a platter.

[music]

David: That's Dawn Wooten, the whistleblower and the revelations about the Irwin County Detention Center in 2020. Our story continues in a moment. This is the New Yorker Radio Hour.

[music]

David: This is the New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. We're listening to a story about an extraordinarily brave woman named Dawn Wooten. Wooten is a nurse in her 40s, but she's got five kids. In 2020 she was working at the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia. It's an ICE facility run by a for-profit company. Wooten learned about medical maltreatment of female detainees at the center. Some truly heinous abuses were being committed. Working with an organization called Project South, Wooten helped file a complaint with the Inspector General of the Department of Homeland Security, but after that revelation became big news, Dawn Wooten's own ordeal just began. We'll pick up your story there.

Ms. Wooten: My baby was at school, and somebody called me and said, "We're going to kidnap your children." My son told me there was a car that hung outside of the school that they were attending every day for about a week. I don't know if somebody wants them or not or if somebody is after my kids to hurt me because they feel like I've hurt them because I spoke up for something that was right.

Sarah: You can imagine that this kind of blowback would be so hard to navigate. Frankly, Dawn was lucky in this case to have an attorney. She also had the support of grassroots groups she was working with like Project South, which arranged for security for her.

Ms. Wooten: We were whisked away under security for a couple of months. Live at hotel to hotel. Every so often we had to leave a hotel in Atlanta to go stay at another hotel. It was very, very depressing. With kids in the beginning, it's an adventure but by the time you get to the third hotel, they're tired of being in a hotel 24 just about 7. We only came out to eat and we're backing in. Then going to strange places to wash clothes. It was just not home. It was very, very depressing. I wound up on antidepressants and my child on antidepressants and anxiety. It was mortifying.

Sarah: Do you remember any of what they would ask you during that time or what they would say during that time?

Dawn Wooten: My daughter, she will be 20 next month. She's 19. 18 at a time, so she's got her first boyfriend at the time. They're having to talk by phone not being home. She's like, "I hate it. I really hate it." She's like, "Mom, I'm glad that you spoke up, but I hate this. I hate it." I had to sit down and talk with her and say hey, "Sometimes I feel like you. Sometimes I'm like, 'I should have kept my mouth closed.'"

Then I have to shake myself and say, "Wait a minute. What if it was you?" I brought it to her that way. "What if it was you wanting to bear children or you wanting to be heard? You wanting to know what was going on and nobody had any answers for you? That's kind of scary, isn't it?" She was like, "Yes ma'am." I brought them in that way and what we're really standing for in that moment.

[music]

Sarah: Let's talk about the effects that that's had on you financially. It sounds like you've gone through this stretch having a really difficult time finding work elsewhere.

Ms. Wooten: It has. When it started, there was a GoFundMe out there at first. That first GoFundMe did help me catch rent up. I was caught up with the rent here, a few bills, I was able to catch my vehicle up because they were getting ready to drag it or repossess it and then not knowing. I was not thinking that I was not going to be employed so pay things off, got things, bought things because I didn't want any overhead things and the kids need it. That money just went like the wind blowing a grain of sand.

[music]

Sarah: At this point, you might be thinking, "Don't we have whistleblower protections in place that would help someone in Dawn's position?" Maybe you've even seen in the news stories about whistleblowers who have made millions of dollars coming forward about corporate wrongdoing, but the truth is there is no single law that protects whistleblowers. It's actually a very complex patchwork of laws and protections and those protections really depend on what kind of employee you are, the kind of information that you're disclosing.

In Dawn's case, her main option was to file a whistleblower complaint with a incredibly backlogged system at the Department of Homeland Security, at the Office of the Inspector General. After that there was very little she could do but just wait and wait some more for the government to act. During this time she's trying to find steady work, she's applying to job after job. In fact, her lawyers actually sent me a spreadsheet that showed more than 100 jobs to which she'd applied, and that included COVID vaccination jobs, jobs doing COVID tests with the nasal swabs, jobs in palliative care, and nephrology.

Ms. Wooten: I was actually employed with the local hospital here, their nursing home facility 20 minutes from here. One of the nurses called me and said, "Dawn, they just took you off payroll."

Sarah: Oh, my God.

Ms. Wooten: My supervisor there at the time didn't even have the decency to call me and say, "Hey, Dawn, we took you off. You're a liability, whatever, whatever." I'm thinking, "Okay." Here I am going to McDonald's. I went to the McDonald's here in Tifton, I was going to flip some burgers as a nurse. The girl recognized, "You're so and so's mama." She calls my daughter's name, "Yes, [unintelligible 00:16:59]." The manager comes out and was like, "Well, I better call the main office." I never heard anything back from McDonald's. I was like, "Well, darn, I can't even flip burgers?"

Sarah: It's wild to think at a moment when our country so desperately needs nurses in the midst of this pandemic. It sounds like most of the time you just don't hear back at all?

Ms. Wooten: Or if I hear back from somebody they're calling me saying, "Hey, we can interview you." They do their research and somebody calls back and say, "Oh." Like I had the nursing home here in Tifton. I had them to call me and say that me and my daughter were hired. I'm like, "Yes, this was open last year. We're going to go to work." She calls me back on a Saturday and say, "I'm sorry, Ms. Wooten.

They did some hiring over the weekend. If anything comes open I'll call you." I waited a week and I call back and I pretended to be somebody else, and I said, "Hi, my name is Melissa. I'm calling from Tifton, Georgia, and I'm a LPN, I've been nursing for about 12 years, do you have any open positions?" "Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. We need nurses like today. We need nurses like today." Who can't put two and two together to realize that it's connected to the Irwin County Detention Center? [laughs]

I'm like, "I don't know what I'm going to do." I'm falling further and further and further and further behind financially. Family is like, "Well, we're kind of needy ourselves." It's not that you can go to family and say, "Hey, I need my [unintelligible 00:18:33]." $1,100 for rent is not a lot to come by. Now I'm back in the same boat with my truck $400 a month. Back at $1,300 in. I had to tell the lady, I was like, "Look, I'll park side of the road. You can come and pull it. Not even going to fight with it. Once I get back up on my feet I'll just get me something else." To the point to where, "Hey, I've got a vehicle. Now the motors blown up in it. That's where I am now. The motor’s gone in it."

Sarah: It sounds like right now you currently do have this nursing home job, but that you've basically been having to walk maybe even more than a mile to work. Is that right?

Ms. Wooten: It's probably about a mile. Probably about a mile and maybe an incline, a little over. Not much, but I know it's somehow there [unintelligible 00:19:20].

Sarah: This might be a hard question, but I wonder if you could take us to the lowest moment since all this happened for you.

Ms. Wooten: I was in a motel room dealing with security. Not that we had been arguing because, at one point, security became very unprofessional. They were cursing each other out and one day they want to take us here and I have these kids and we're hungry. We don't care if y'all have to figure it out, drive each other, we're hungry. At this point, it's like, "Forget it." We go back in the room and we sit.

It's like if I had just kept my mouth closed, we wouldn't be in this situation. This is my conversation out loud and my kids are sitting. I'm apologizing saying, "I should have never brought y'all. I took you out through this. I never thought that y'all would be going through this.

Hey, I never thought it was going to be this way." It got to a point, to where it was like if I disappear then y'all would be good, y'all would be good because nobody will talk about me, nobody will discuss me, I'll be a figment of their imagination, I'll be a memory. Then I sit about 20 minutes and I have to pull myself back in and I'm looking at my children going, "I can't die now. I mean not now. Dawn, you can't die now. Dawn, you can't get depressed now. Dawn, you can't clam up now." But I shake myself and I'm like, "Wait a minute." You lay down, you wake up the next day and it's like, "Okay, so who wants to hear my story today?"

Sarah: What do you wish people knew about your experience looking over everything that you have been through in this past year? What do you feel like people don't know about the long-term aftermath of what you've faced?

Ms. Wooten: It's okay to blow to whistle. It is okay. This is going to sound probably weird, but you need to prepare a readiness course. Life itself did not prepare me for, "You possibly won't be employed. If you speak out you won't be employed." I'm sort of glad you don't get that in the beginning because I probably would not have, but it's feasible, it's workable. In the long run, you're saving somebody's life. In the long run, you're saving somebody's productivity and mental welfare and wellbeing even if it means that you at some point pay a price for yours.

Sarah: In may of last year, the government made a really big announcement which is that they were terminating their ICE contract with ICDC, after the revelations that had been brought public by Dawn and by the detained women and by the activists who'd been fighting for this for so many years. As you can imagine that was a really big victory for all of them, but it was also very far from the end of the story because Dawn and the women are still waiting for justice. Many of the women have filed a civil lawsuit and that is still winding its way through the courts. For Dawn and her case, her whistleblower retaliation complaint has still not been resolved.

The government legally had 180 days to respond and they blew past that deadline, they asked for more time and then they blew past another. Dawn's lawyer Dana Gold at the government accountability project, told me that her team is fighting to change federal policy so that people like Dawn with a credible claim could get some temporary relief while they wait for the deeper investigation which can be a really long and costly process.

Gold stressed that the protections that are in place for whistleblowers, especially low-wage ones really just are not enough. The question that sticks with me is what would it look like if we actually created an environment in which a whistleblower who wants to step forward and do the right thing can feel protected to share information that really in the end protects all of us?

Sarah: It's like everybody's getting answers but me. Everybody's getting relief but these women. We're the only two left hanging in the balance. These women still have scars that they have to carry from here until the end of their time on this earth. My voice with their bodies paved the way for the decision to be made so what's holding up? Each day is lost time for me, it's lost time

David: Dawn Wooten is a nurse in Georgia. The company that operated the Irwin County Detention Center, LaSalle Corrections did not respond to our request for comment about Wooten's retaliation complaint. About the allegations of mistreatment of detainees, they previously issued a statement saying this, "LaSalle Corrections is firmly committed to the health and welfare of those in our care, we are deeply committed to delivering high quality culturally responsive services in safe and humane environments."

Sarah Stillman is a staff writer for The New Yorker and recently she reported for us about the migrant workers who go around the country repairing towns after hurricanes and other climate disasters. It's a really fascinating piece and you can find it on the podcast of the New Yorker Radio Hour anywhere that you go to, to find podcasts.

[music]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.