The Photographer Who Documented a Long-Forgotten Pan-African Festival

David Remnick: 46 years ago a young photographer named Marilyn Nance got the opportunity of a lifetime. Nance was a 23-year-old student at the Pratt Institute, an art school in Brooklyn. She had never left the country, but she became one of the official photographers to document a festival called FESTAC '77, which was held in Lagos, Nigeria. FESTAC was huge, an arts and culture festival featuring artists from across Africa and the diaspora. Nance spent a month soaking up the atmosphere and preserving its spirit in photographs that are only now being published in a book called Last Day In Lagos. Marilyn Nance talked with our staff writer Julian Lucas about her experience and why so many of us have never heard of FESTAC '77.

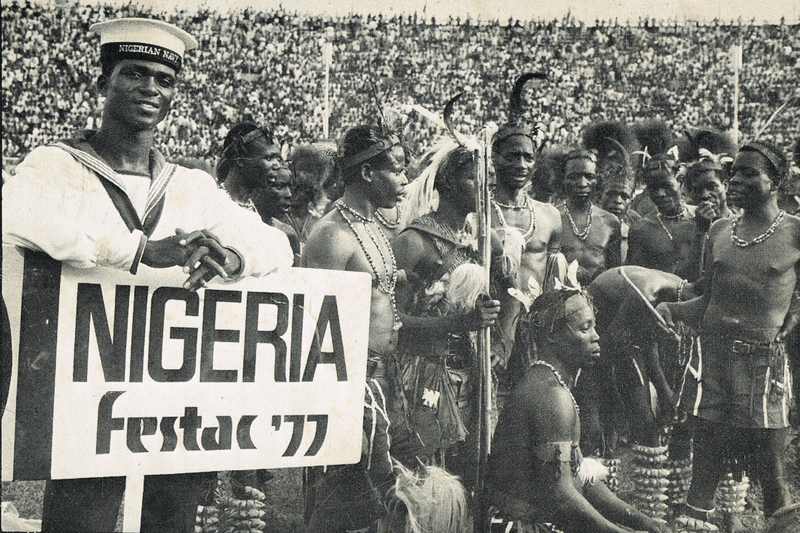

Marilyn Nance: FESTAC '77 was like Woodstock. It was like a biennial. There were art exhibitions. It was like the Olympics because we all marched around a stadium in our national dress. It was a meeting of African folks from all over the world. All our roots and our part in Black culture and African culture was incredible. I looked around at the sea of Black faces and I had never seen a collection of Black people larger than New York, larger than America. This was the largest collection of Black people I had ever seen in my life and I felt the earth move. I felt that there was a place there for us and we are not Nigerian. We are not African, but we are an African people. This is the motherland and it's taken me all--

Julian Lucas: You were involved in the Black arts movement from a young age and I wonder if you had a sense of the significance of this festival before you went?

Marilyn: I did, but I never thought that I would get to be this age. I thought that I would be talking about FESTAC in 1978 and not in 2022. I did not know then that it would be disappeared from history. I thought it was something that was so big to me into all the other participants that surely this would be something that would resonate for years and years to come. I think that if there's some tragic something that happened, everybody would remember, but it was a joyful thing. I guess maybe there was no investment in celebrating Black joy.

[music]

Singers: Welcome, welcome, ladies and gentlemen. You are welcome to Nigeria. We are the FESTAC is taking place here Nigeria in Africa. Welcome, welcome, ladies and gentlemen. You are welcome to Nigeria.

Julian: It's really extraordinary how much it's been forgotten when you see your photographs and you see Stevie Wonder, Miriam Makeba, Sun Ra in this wonderful procession of nations.

Marilyn: I've been witness to a lot of extraordinary events and it points to the fact that a lot doesn't get said. I knew that even as a youngster. I knew the way that our lives were regarded and I knew differently. I think that's why I set upon becoming a photographer because there are things that I saw that I just wanted other people to witness as well, but making the photographs is one thing. Getting them seen is quite another thing.

[music]

Queen Mother Moore: They want the oil, but they don't want the people. They want the oil, but they don't want the people. They want the oil, but they don't want the people. Thy want the oil, but they don't want the people. They want the oil, but they don't want the people.

Julian: I wanted to ask you about a great photo you took of Queen Mother Moore.

Marilyn: I love that picture.

Julian: I wonder if you could tell us a little bit about her and why it was so significant that she was there at the festival.

Marilyn: At the making of that photograph, Queen Mother Moore was making some exclamation, which I wish I remembered, but I have the photograph. I don't know what she said.

Julian: It's a really regal photograph of her and what I loved after reading about her was this is someone who had been an activist since the Scottsboro Boys, who had been part of Marcus Garvey's movement, which of course was so centered around returning to Africa. Then decades later, here she is in a very different cultural political moment.

Marilyn: Well, I wouldn't say different. I would say it's a continuum. She talked about reclaiming your African personhood. She talked about reparations. She was the connecting thread. There were numbers of distinguished elders, that was her position. Joseph Delaney was there, who was part of the Harlem Renaissance. There was Ernest Critchlow, Noddy Kamar, elder musicians, young people. There was a whole continuum of the Black creative spectrum in the visual arts, the spoken word. Jane Cortez was there, Melvin Edwards.

Julian: Since you're mentioning all these artists and performers, I remember reading that at one night in the FESTAC Village where the delegates were staying, Stevie Wonder came and-

Marilyn: Just showed up.

Julian: -just hung out with the delegation.

Marilyn: He showed up.

Julian: What do you remember about that?

Marilyn: I don't even remember how we knew that he was there, but there he was. It was almost like a campfire situation except for there was no fire. I don't remember what he said, but we were just like, "Oh, Stevie Wonder, Stevie Wonder."

[music]

Stevie Wonder: Music is a world within itself. There's a language we all understand.

Marilyn: All of the action was in FESTAC Village because all of the delegations, all of the contingents were there and there was music. I would lay down like I'm exhausted, but then you'd hear drums over here and music over there. You could not rest in FESTAC Village and maybe Stevie heard about that. Showed up with Samella Lewis and Louis Farrakhan and Jeff Donaldson.

[music]

Singer: East or west, Africa is my home.

Marilyn: It's not like I have a fantastic memory, but I do have photographs and that's how I remember. I astound people with my 'memory,' but I see these images a lot.

[background voices]

Reporter: There was Mozambique, uniformed and military outfits reflecting their difficult armed struggle for independence. The sneakers they wore lightened their feet as they did traditional dances. From Europe came the Afro-Swedish and the Afro-Irish. Several hundred Blacks from the United States participated. For the most part-

Julian: I wonder if you could take us to the Parade of Nations, the opening ceremony? Some of the most immediately spectacular photos in your book are from that 54 countries. You have Malian kora players, traditional masquerade performers-

Marilyn: It wasn't in a-

Julian: -singing groups.

Marilyn: -a book. We've only seen those images in books, but there we are and they're real people. They're looking at us like we've only seen these people in movies or in books. We were just all staring at each other like, "We're here."

Julian: An element of culture shock, I'm sure.

Marilyn: Yes, and it wasn't like I was looking at the Parade of Nations. I was part of that Parade of Nations. We were just amazed at each other.

[music]

Singer: [foreign language]

Julian: I know it wasn't just a Black cultural festival. It was Black and African. Could you explain that?

Marilyn: Algeria was represented, Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia. These are countries on the continent of Africa that may not have claimed Blackness, but they're African and then there were people from the diaspora who claimed Blackness including, I was really surprised to see the Australian contingent because-

Julian: Right.

Marilyn: -we had been educated to-- believe that Australians were Asian. I don't know what we were told, but here they were, dark-skinned people at a Black and African festival and I was like, "Hmm."

Reporter: On stage in the Nigerian National Theater, Sun Ra and his orchestra.

[music]

Julian: There's a great picture of Sun Ra's rehearsal shed in the book with people just climbing on ladders, crawling-

Marilyn: Under.

Julian: -to look underneath the wall, standing on tires. To me, that really gets at what the festival was about and what your method of photography is about this. There's not really a boundary between the spectator and the action. You're part of it all.

Marilyn: I was one of those people. I don't think I got on any ladders or anything, but I got down low to make some photographs. People crowded around the rehearsal shed just to see what folks were doing. That one image points to maybe three or four rolls of film [chuckles] of that one rehearsal. It was amazing just to see acrobatic troops.

Julian: The Flying Souls.

Marilyn: The Flying Souls, but there was a troop-- and I'm not sure what country they were from- where this man was doing things with his body and bending and I'm looking underneath and finding a space. No one made space for me because I had a camera.

[laughter]

Marilyn: I had to find a space like everyone else had to find a space.

Julian: I wonder if you could say something about how this book came together? How did Last Day in Lagos get made 45 years after you flew back?

Marilyn: Wow. Well, first of all, Last Day in Lagos came out of my knowing that I had work that I wanted to share with a younger audience. There was a group called the Brooklyn Photo Salon, young photographers in Brooklyn. I was like, "Brooklyn Photo Salon? Young people doing? Let me see what's going on." I started going to some of the meetings and introducing my work. I did a lot of networking, a lot of talking, and going places. I wasn't sitting waiting to be discovered, but it was in Johannesburg. I was presenting the FESTAC photographs at the Black Portraitists Conference in 2016. I was there with my husband, Al Santana, my archive fellow, Valerie Caesar and the artist, Valerie Maynard. We did the panel on FESTAC and there was a panel of young people, and Ole Remi, Onabanjo was on the panel.

Julian: This is your editor?

Marilyn: Right, my editor. I introduced myself to her after the panel was over and I said something about FESTAC and she was like, "Of course, I know what FESTAC is. I'm Nigerian."

[music]

Marilyn: Anyway, when she looked at the work, she said like, "I want to do a book."

Julian: She recognized its importance.

Marilyn: Right, right away. My joke to her was like, "Remi, I'm going to let you discover me."

[laughter]

Speaker 4: You are still taking. It's true. Where will the whole western world be without be without Africa? Our cocoa, our timber, our gold, our diamonds, our platinum, our whatever? Everything that you are is us. I am not saying it. It's a fact and in return for all--

Julian: Well, there's something elegiac about your title Last Day in Lagos because this was the last festival of its kind. A high point of this Pan-African spirit that wasn't repeated. It's been 45 years, as you mentioned, since FESTAC. I wonder if you could say something about what happened? Why didn't these photos come out?

Marilyn: That's not my business. I did what I did. Ask them, whoever them is. Ask the historians. Ask the publishers. Ask all those people who ignored the work. I did the work. I didn't hide it.

Julian: Did you try to have them published when you came back?

Marilyn: Yes.

Julian: What happened? How did people respond?

Marilyn: I can't tell you how they responded, but I had to go on living, so I started working in advertising. I've taught school. I've worked as a teaching artist. I pretty much know my worth. I know the worth of this culture. I know the value of this event. Even if you don't know it, I know it. I just had to wait until like a new generation came. I think things happen and roll out when they're going to happen and maybe this is the right time for this.

[music]

[laughter]

Julian: Well, I think that's a great place to end.

Marilyn: You have a good radio voice.

Julian: Thank you.

Marilyn: Yes. You'd think you--

Julian: You have a great radio voice, though.

Marilyn: No.

Julian: Make me sound good, too.

Marilyn: [laughs]

[music]

David: Marilyn Nance's photos of FESTAC '77 appear in the Last Day in Lagos, which came out recently. Julian Lucas is a staff writer covering culture of all kinds for the New Yorker. The music and clips we heard are from a FESTAC '77 mix tape compiled by Chimurenga in 2020 and reproduced courtesy of Chimurenga.

[00:16:20] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.