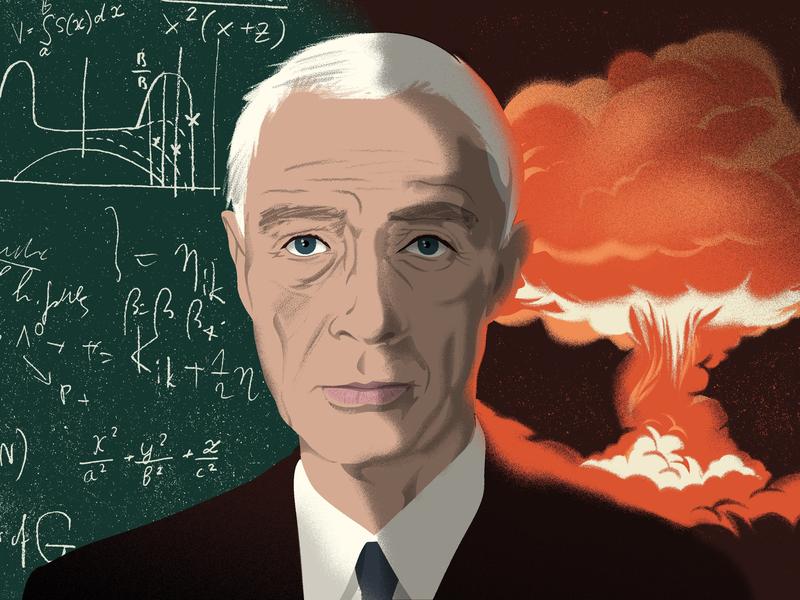

Adapting Oppenheimer’s Life Story to Film, with Biographer Kai Bird

David Remnick: This week, Christopher Nolan's film, Oppenheimer, which is about the father of the atomic bomb. Its director Christopher Nolan worked on science fiction movies like Interstellar and Inception, as well as the World War II epic and I think his best movie until now, Dunkirk. To make Oppenheimer, Nolan relied on the astonishing biography, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer written by Kai Bird and the late Martin Sherwin. American Prometheus won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize. Nolan took some artistic license as you might expect, but Kai Bird is credited as a co-writer of the film, and he told me that no one stayed pretty faithful to his book. I spoke with Kai Bird last week.

Now, Kai, Christopher Nolan, the director of the film has called Robert Oppenheimer the most important person in the history of the world. As his biographer, along with Martin Sherwin, of course, is Nolan right or is he just kind of hyping the film?

Kai Bird: Well, when I first heard him say that, I thought that's a little bit of a hype quite frankly, but the more you think about it and the more I revisit my 18-year-old book, it's true. Oppenheimer gave us the Atomic Age, and we're still living with it was a revolutionary thing. What really makes it an incredibly fascinating story is the arc of his triumph in 1945 and then nine years later, his humiliation, the tragedy of his downfall.

David Remnick: Exactly. Both in your book and in the film, Oppenheimer's role at Los Alamos is, if anything, the narrative midpoint of the story almost exactly in the book, the prosecution of Oppenheimer as a person to suspect to hold a security clearance suddenly, and then his horrific ruin in which we see him almost waste away is in many ways, the harder thing. Why was he prosecuted? Why was he prosecuted the way he was?

Kai Bird: Well, he had a sketchy background. Marty and I debated amongst ourselves about what does the evidence show, and we concluded that he was pink but not red, [laughs] that he was a fellow--

David Remnick: For the younger listeners who aren't used to the vocabulary, what does that mean?

Kai Bird: That means that he was a fellow traveler, that he was a man of the left at Berkeley in California in the 1930s in the midst of the Depression, not surprisingly, capitalism seemed to be failing. The Spanish Civil War was raging. Fascism was rearing its head in Europe, and he met a young woman named Jean Tatlock, who was a member of the Communist Party. He fell in love with her, and she railed at him for being a nerdy, a political university professor and urged him to become more politically involved, and so he did.

We examined the evidence very carefully and argued amongst ourselves, and we concluded that he never became red, he never joined the party, he never had a party card. He did contribute money to the Communist Party-sponsored causes like integrating the public swimming pool in Berkeley and raising money for an ambulance to send to the Spanish Republic but that he was not the kind of man to submit himself to party discipline.

David Remnick: But surely the authorities, the military establishment, the national security establishment, before they installed Oppenheimer as the head of Los Alamos, a job of immense consequences, and remember, he's only in his mid to late 30s, they must have known about his political background then when they installed him.

Kai Bird: Absolutely. When General Leslie Groves hired him as the scientific director at Los Alamos, he had read his FBI file. He knew that Oppe had all these associations.

David Remnick: Why was it okay in 1943?

Kai Bird: Well, they needed him, and this was quite common. Many of these university professors that they were recruiting into the Manhattan Project had been politically active, had been on the left. What changed was, after the war, Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, begins to go public with his criticisms and his worries and warnings about relying--

David Remnick: His ambivalence, yes.

Kai Bird: His ambivalence about the bomb.

J. Robert Oppenheimer: I have been asked whether in the years to come it will be possible to kill 40 million American people in the 20 largest American towns by the use of atomic bombs in a single night. I'm afraid that the answer to that question is yes. I have been asked whether there are specific countermeasures against the atomic bomb. I know that the bombs that we make in Los Alamos cannot be exploited by such countermeasures. I do not think there is any foundation for the hope that such countermeasures will be found.

Kai Bird: He gives a speech three months after Hiroshima, in which he says in Philadelphia, "You might think that this is an expensive weapon because it costs $2 billion, it's actually cheap, and any country, however poor, anywhere in the world that decides they want to build this thing will be able to do so. You may think that it's a weapon for defense, it's actually a weapon for aggressors. It's a weapon of terror." Then he goes on to even say it was a weapon that was used on an essentially already defeated enemy, so he's--

David Remnick: That phrase is key, the already defeated enemy. He came to believe, and I don't know if he believed it while he was at Los Alamos, or said so, but that perhaps the bomb should have been used as a demonstration weapon to scare the Japanese government into submission rather than dropping it on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Kai Bird: Well, before Hiroshima, this was debated. Oppe actually took the position that it could not be demonstrated on an uninhabited island or in the Bay of Tokyo, that he feared and he believed, actually that it had to be demonstrated in combat.

David Remnick: Why?

Kai Bird: Because otherwise, no one would understand the terrific horrendousness of this horrible weapon. This is precisely the argument that he used in the spring of 1945 when he faced a near revolt among his own physicists at Los Alamos. There was a public meeting inside the barbed wire facility in which they discussed, "Why are we working so hard to build this thing when Hitler is dead, Germany is defeated?" He stepped forward at the end of the meeting and said, "Well, I want to remind you that when Niels Bohr arrived in Los Alamos on the last day of 1943, he had one question for me. He said, 'Robert, is it big enough? Is it big enough to end all war?'"

Oppenheimer had convinced himself that this was a necessity to end all war. All war. His hope was that this weapon was going to be so terrific that it would convince people that we could never have World War like they were engaging in at that moment.

J. Robert Oppenheimer: A short time ago, an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima and destroyed its usefulness to the enemy. That bomb has more power than 20,000 tons of TNT. It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe.

David Remnick: There is a remarkable scene in the film, and it's certainly elucidated at length in the biography. Oppenheimer is invited to the White House, and he's brought to see Harry Truman, and Oppenheimer expresses words of remorse. He says he has blood on his hands, and he uses the word sin. Suddenly, Harry Truman, who thought he was going to be congratulating him, is disgusted. He calls him a crybaby and tells his aide he never wants to see that guy again. Never wants to see him again.

What are we to make of Oppenheimer's ambivalence? On some degree, you think it's almost as if he wants the glory, and he also wants to express this ambivalence in a very public, moral way. How do you assess his moral choices there and the way he behaved?

Kai Bird: Well, he's very complicated, and he's highly intelligent, so he's capable of understanding and holding in his head contradictory ideas. Let me answer your very good question with this anecdote. I discovered late in our research that Oppenheimer's last secretary at Los Alamos was still alive. Her name was Anne Wilson. She was living in Georgetown. I tracked her down, and we had a terrific interview, which at one point she told me that she was walking to work one day with Oppenheimer. It was just after the Trinity test [crosstalk]--

David Remnick: The great test of the atom bomb for the first time?

Kai Bird: Right, on July 16th, 1945. Suddenly, she hears Oppenheimer is muttering to himself, "Those poor little people. Those poor little people." She stops him and says, "Robert, what are you talking about?" He says, "The gadget was successfully tested. It is now going to be used on those poor little people, a whole city because there is no other target. There's no military target large enough. It has to be a city."

When I went back and told Marty Sherwin about this interview and this story, he remarked, "Look at the chronology. This had to happen in the very week that Oppenheimer was meeting with the bombardiers that were going to be on the plane. He was instructing them at exactly what altitude the bomb should be detonated to have the maximum destructive effect and that it should be dropped on the center of the city." Here, he was doing his duty, presenting this weapon of mass destruction to the politicians in Washington for them to decide how to use it, but he knew it was going to be used.

Yet, he was also capable of extreme empathy for the victims, and yet he feared-- I think he just felt that the world would not understand unless it had been demonstrated on a target. He feared that if it was not used or the war ended without the use of this weapon, the next war was going to be fought by two nuclear-armed adversaries and it would be Armageddon. He also fell in love with the notion that his status as a celebrity scientist after Hiroshima that he should use it. Use it to educate people about the dangers of this weapon and to educate the politicians.

Of course, that's why he began speaking out more and more. He came out against the building of the hydrogen bomb after the Soviets tested their own atomic bomb in 1949. By then, he was saying exactly the opposite of what everyone in the national security establishment wanted to hear. The Army, the Navy, the Air Force, they all wanted to spend more money on more of these weapons, and here, the father of the atomic bomb is saying, "No, no, we should be talking about international control and disarmament and regulation of this new technology."

He was a threat, so he had to be brought down. In the words of Edward Teller, he had to be brought down, defrocked in his own church. This is what happens with the security hearing in '54. On the very eve of the 1954 hearing coming to that, he has to go down the hall to Albert Einstein's office at the Institute for Advanced Study-

David Remnick: At Princeton?

Kai Bird: -at Princeton and explain to Albert that he was going to be absent for a few weeks because he was being hauled before this security hearing and his loyalty to America was going to be questioned. Einstein just reacted desperately and said, "Robert, you're Mr. Atomic, why should you subject yourself to this witch-hunt? You should walk away."

David Remnick: What were his options? Could he have walked away as Einstein was suggesting?

Kai Bird: He could have walked away. In fact, ironically, his security clearance was expiring in just a matter of weeks, and he could have just let it expire.

David Remnick: And go on leaving the Institute for Advanced Study in relatively tranquil circumstances?

Kai Bird: Yes, right, but Oppenheimer was being foolish and naive. He had no idea what he was walking into. Oppenheimer always, he never said that he regretted what he had done during the war. He thought that the atom bomb was going to be discovered someday. His fear was that the Germans were going to get it first, so that motivated him to work harder to get it in 1945. He argued that you can't stop the science but you can try to figure out how to use it, how to integrate it, how to live with it.

In this case, he and Sakharov both believed that it was insanity to rely on these weapons as weapons of defense. They're not defensive weapons. We see this now with the war in Ukraine, where loose talk is made about using tactical weapons as if they were really military weapons.

David Remnick: Tactical nuclear weapons.

Kai Bird: Tactical nuclear weapons. They're not battlefield weapons. They're simply weapons of terror. If Putin ever used one, he would use it in a psychological fashion to try to change the dynamics in the halls of Congress and the White House but it wouldn't change anything on the battlefield.

David Remnick: You've talked about Oppenheimer as a public intellectual and a dissident. Do you see any parallels in the contemporary world of a figure like Oppenheimer and how scientists do or do not speak out?

Kai Bird: This is one of the lessons that's very current about the Oppenheimer story. What happened to him in 1954, I believe, sent a message to several generations of scientists here in America but abroad that scientists should keep in their narrow lane. They shouldn't become public intellectuals. If they dared to do this, they could be tarred and feathered. If they dare to speak out about politics, that would somehow muddy their integrity as scientists.

This is odd because we live in a very complicated society drenched in science and technology, and yet, you'd think that we would have well-respected scientific figures who are speaking out and debating in a civil manner the way forward, how to make rational decisions about artificial intelligence, for instance, or some of the biomedical breakthroughs that are happening. Yet, we seem to leave that conversation to non-expert politicians. It makes no sense. Yet, I think this happened because partly of the seeds that were planted in the '54 hearing against Oppenheimer.

David Remnick: At the screening, we were both at the other day for this film, at a conversation afterwards, the name Tony Fauci came up. Explain what the context there is in the comparison.

Kai Bird: Well, it's just, the same thing that happened to Oppenheimer, in a sense, happened to Tony Fauci. Tony Fauci is a dedicated public health official, who in the midst of the pandemic was trying to give scientific advice to the average citizen on how to cope. Of course, his advice had to sometimes change because new facts became available. Of course, this is what happens in science. We're constantly testing our theories against experimental facts. It's a shame that Fauci's integrity was questioned by our politicians.

David Remnick: Kai Bird, thank you so much.

Kai Bird: Thank you.

David Remnick: Kai Bird is the co-author of American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. The book won the Pulitzer Prize, and Bird is credited as a writer of Christopher Nolan's film, Oppenheimer, which is just out.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.