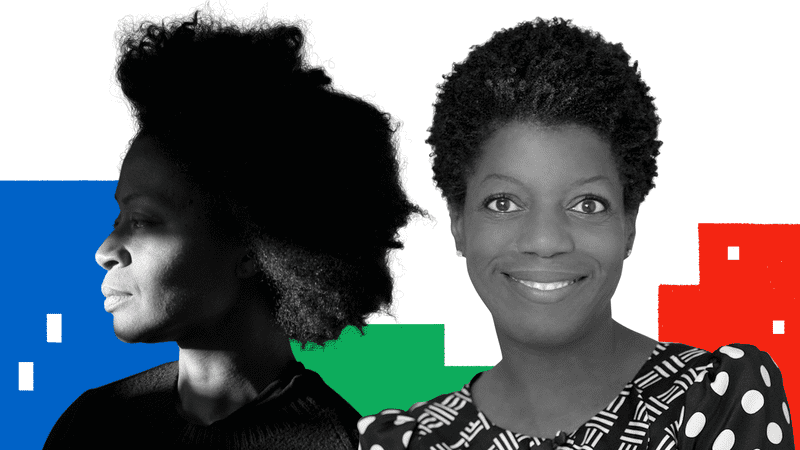

Kara Walker Talks with Thelma Golden

David Remnick: Since coming to prominence, the artist, Kara Walker has asked us to deal with some of the most insidious parts of our history. Walker became famous with paper cutouts in a style that seemed Victorian. She borrowed racist imagery from a past century to explore race, gender, violence, and power in our own time. While the imagery may be painful, Walker's work is also seductive, beautifully realized in forms that are uniquely her own. She joined us last week at the New Yorker Festival for a conversation with Thelma Golden, the director and chief curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem.

They discussed a work from a few years back, truly one of a kind with a title, A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby. It's a Sphinx made in sugar, constructed in a former sugar plant in Brooklyn. It was 75 feet long, really monumental. As the sugar fermented, the smell also became monumental. The line to see the work was sometimes at hours long. Here's Thelma Golden with Kara Walker.

Thelma Golden: The marvelous sugar baby very much seems to be a work on one hand, which calls into a moment that, I think, you have been in for some years, which really intersects with the conversation in this moment about monument making. So that your work seem to be, in some ways, responding to the effort towards monument but, in many ways, creating a corrective in them, but also, a subtlety. Also feels as if it's a work that really also talks about this relationship that you have through your work with audience. Could you talk a bit about that work in process, as it relates to its form but also its reception?

Kara Walker: Yes. The process was arduous, it was long. My brain doesn't work the way I wanted to when I needed to do things. There's drawing, there's crying, there's reading, there's writing. I was making PowerPoints that confused people that helped my mind sort of accumulate images, and ideas, and feelings. Ultimately, I realized, “Okay, it is really about the public. It is about creating a space, where I can take these ideas about slavery, about the new world, about sugar, about the thousand years prior to the New World discovery, where sugar was a refined treat for only the most special, a very-hard-to-get treat.

All the way into the sort of economics of slavery, the hardships of the sugar plantation, the botany of the sugar cane, and how to distill that or literally refine it into something that is iconic and easily digestible, but also speaks about the sort of destruction of humanity that this beautiful substance, tasty substance has come to represent and has come to be. I thought, “I actually have to think like the Havemeyer brothers. I actually have to think about like, “I have a sugar refinery, how do I entice and repel at once?” Ultimately, I started thinking about the Sphinx.

I started thinking about tourist attractions. I started thinking about ruins, and ruins, and ruins, and past civilizations, and that this place, this plant was about to be destroyed. It was emblematic of a past civilization, civilization that we are soon, no longer to be a part of.

Thelma: You spent some time there watching the audience engage in that work.

Kara: Yes, it was a big audience. I think they had 130,000 people over six weekends or something, crazy lines. I went a few times just to be there and see it, because it was the thing to be seen. I couldn't believe that I was responsible for it, because people had so many varied and amazing responses to the work, tears, and worship, and selfies, and rudeness, and tasting. It was really a sensory experience.

Thelma: Really digging into this idea of monuments, I'd love for you to talk about what it meant to grow up in the literal shadow of Stone Mountain.

Kara: Well, Stone Mountain just briefly is-- we moved from Decatur to Stone Mountain, when I was 15. The first thing that happened was we got a notice, an American flag and a notice in our mailbox about the clan rally down a Memorial Drive. This was in 1985. Because the clan at that time still owned a part of the land that-- Stone Mountain Park is occupied by the park. At the time that I moved there, I was not really keen on visiting the park, but it was there, and it was the destination for everybody in my school and neighborhood. It's been this looming, strange, permanent artifact that I've learned more and more about over the last 25 years, I guess.

Thelma: You've been making art since you were a child. I want to know, when you thought you were an artist, when did the idea occur to you?

Kara: It's funny, because I think, yes, I always kind of thought of-- “My father is a painter. I spend a lot of time as a child around people who said they were artists,” so I just thought I was an artist, but I didn't really realize that I wasn't an artist until I was in graduate school. I started to really take stock of my own privilege in a way, the privilege of being around artists. I thought, “Well, I want my work to have meaning. I want my work to have reach. I want my work to have range.”

The work that I was looking at that I really thought that really spoke to me was work that hit a very hard note, that talked about history, the German expressionists, for just the easy example. There were other artists. I mean, certainly, the work of the Black Arts Movement was really going hard at trying to right the wrongs of our history and to really sort of plumbed the depths of one's personal experience, but as it relates to social experience and social history that I think that I had to grow up into that.

Thelma: You, through your imagination and this engagement in history, have created for many an alternative narrative. So much of your [inaudible 00:07:38] [unintelligible 00:07:38] for me has been about the way in which you've taken a personal path through an imagining of perhaps the stories we haven't heard, or the ways in which perhaps they might not have been told. Can you talk about this role of narrative in your work?

Kara: Sure. I think, again, talking about influences and narrative, trying to understand, where narratives of Black womanhood exists there, primarily, at least in the past, in the form of personal slaves narratives and narratives of overcoming hardship, or trying to overcome hardship. The truth, the documentary, the personal documentary, the biography, the autobiography, and within the autobiography, I guess, there's this kind of problem of audience.

In the course of autobiography, you have unsavory elements that maybe an audience of good Christian abolitionists doesn't exactly want to hear, so then euphemism becomes key. Or a strong euphemism but key euphemism about rape, perhaps about a strange feeling of complicity that perhaps the narrator's trying to wrestle with. How did I wind up in this situation, while I was trying to protect my children, or was trying to set my children free, or whatever?

There's a complexity, I think, to the experience of a woman in slavery that is harder to narrate. That space is very interesting. The space of what's unspoken, what's unsaid, because it is both unsayable and very familiar. Just speaking abstractly, that's where the silhouette or the sort of as a blank space kind of becomes the representative of that.

Thelma: Yes. Can you talk a little bit about what led you to the silhouette as a form.

Kara: It was the blank space, really. I was thinking a lot, in part, about the blank spaces within these narratives and thinking about my own heart, and the stuff that I'm made up of. I was really thinking about the sort of compression of stereotypes, and ideas, and misrepresentations coming from outside of me that were building. Thinking-- just a part of it was an abstraction. Part of it was thinking about Blackness, thinking about skin, thinking about that being a covering rather than an identity.

Of course, I was looking at a lot of historical imagery. I was thinking about identity and I was thinking about my own growth, but I was also linking it with the identity of America. What is its representation? What does it look like? I thought it also looks like this kind of blank space.

Thelma: In so many ways, you mine the horror of what we know is the legacy of slavery, of racism, the violence of it. Can you talk about that part of your process and your practice? What it means to be mining such complexity in the work visually and through length and text?

Kara: I should be able to talk about it by now, but I think as far as part of the process, there's an aspect that just feels necessary. I think that mining my own depths, I dare say I've been accused in my childhood and other parts of my life of being too self-revelatory of, say, seeing the wrong thing in a joking way that is self-deprecating to a fault, or too revealing, or revealing in a way that upsets the group, so I did, I think, at some point you stop talking, and it shows up in the work sometimes without my even realizing it.

Thelma: Well, I think there's oppression to the work. The past moment you said, “My work is all about the now.” It seems to me that even when your work is cited in these historic moments that you are often commenting about what happens present.

Kara: Yes, exactly. I think that what I set out to do in a way worked too well with just to say, “Well, if I pretty everything up with hoop skirts and southern belles, then nobody will recognize that I'm talking about them.” Then they didn't. [laughs] It's like, “Oh, this is the past. It's so bad.” I'm from the past even if I make drawings that suggest that this is what I could have had access to, stylistically or something. It's not the case. I do live here now, and so do you.

Thelma: When I have encountered your drawings, I always think of the amazing Audre Lorde quote, which said of herself, “I am my best work, a series of roadmaps reports, recipes, doodles, and prayers from the front lines.” It feels to me, your drawing practice is somehow embedded and engaged in that idea, that it forms the connected issue between past and present work. Can you talk specifically about this moment of lockdown and then the ongoing period and what that has meant for your work and particularly your drawing practice?

Kara: Drawing, it's important to me just to know that I exist. I think it is the connective tissue between my mind and my feeling, my heart, and the outside. Being able to put it down on paper is really something that I feel is a blessing, a privilege. Also a burden, and a chore [laughs] to have to remember to do it and not forget. It's shocking, and it surprises me every time that, when a drawing feels good to me that I didn't have a thought. I didn't know that it was what was coming, but it makes perfect sense.

I've been doing a lot of sitting down, just very basic, nice sheet of paper, pencils, watercolors, maybe some ink. That's been keeping me going through this period of lockdown, through a lot of ups and downs emotionally, and some losses, and tragedies, hot points here and there. It's like the through-line for me is being able to sit at my table wherever my table happens to be and do some drawings.

[music]

David: The artist Kara Walker, speaking with Thelma Golden of The Studio Museum. Walker's work is on exhibit in Chicago, at the DuSable Museum. Their conversation was recorded at The New Yorker Festival, which is still going on. You can find out more at newyorker.com/festival.

[music]

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.