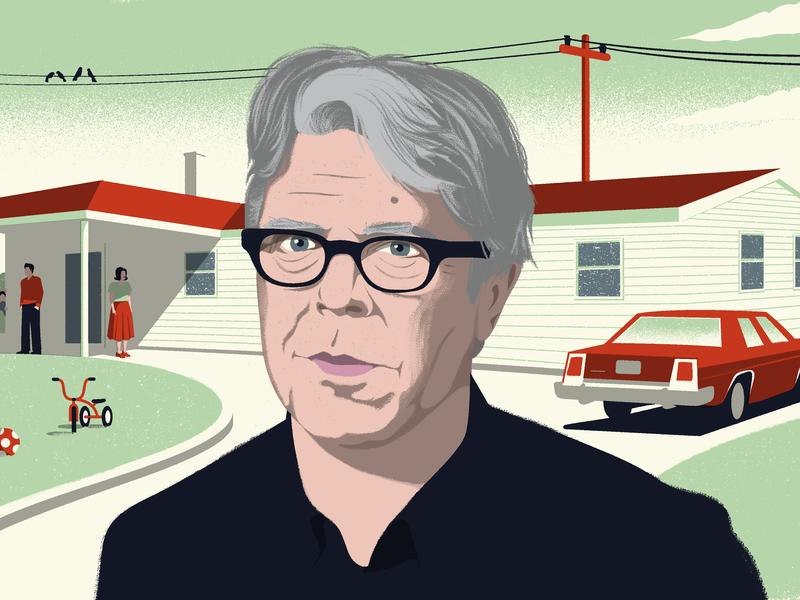

Jonathan Franzen Talks with David Remnick About “Crossroads”

Interviewer: Jonathan Franzen's new novel is called Crossroads, and that title hits it pretty much on the nose. The story is about a Midwestern family at a pivotal moment in all of their lives. It takes place in 1971, which was another kind of crossroads for the entire nation. The utopian ambitions of the '60s seem to have foundered, we were heading toward Watergate, and what Jimmy Carter would later describe as a crisis of confidence.

Crossroads is the first book of a projected trilogy. I spoke with Jonathan Franzen, and we began pretty much, inevitably, talking about the pandemic.

Jonathan Franzen: I was finishing Crossroads during the first four months of the pandemic, and I had an office I could still go to, and we did no socializing, so I could go to bed at 9:00 every night and get up at 5:30, which was fantastic for a writer. More recently, I haven't gotten COVID yet, that's really all I can say.

Interviewer: Well, is that ideal for a writer that, despite the tragedy of it all, and taking that aside, which is very, very hard to do, is that kind of solitude and lack of interruption ideal for you?

Jonathan: Oh, it's perfect. Yes, it's perfect. I try to keep quiet about that, because I know that the millions of people who are suffering, and I just go la, la, la. [chuckles]

Interviewer: Well, let me ask you this, my understanding from talking to our mutual friend, Henry Fender, your editor and mine, is that sometimes in your writing life, the way it happens is, you think and think and think, and that process can go on for a long time, and maybe you're doing other things, and then an idea kicks in, and then in the space of a relatively short period of time, a pretty ambitious novel emerges, is that the way it's happened, now, with this new book, Crossroads?

Jonathan: It's a little different this time. I had a very ambitious project for a single-volume novel with three parts set 25 years apart, each of them, and then when I started writing, I realized I had a whole lot to say about the 1971 portion of the novel, so it turned into a whole book. Maybe it would have been smart for me to say-- There will be a second book with two parts, but for whatever foolish reason, I decided to say, "No, there are going to be two more books."

Interviewer: Just in terms of process, what you say is very interesting, that for years, you're basically thinking.

Jonathan: Yes, it's occasionally, I will take a stab at writing some pages, but these books really are icebergs. There is this 90% below the surface, which is all about figuring out the characters.

Interviewer: Why, at this point in your life, you're in your early 60s, why explore the question of faith at this point in your writing life, it's so central to this book?

Jonathan: For a person who's never been a believer, never had a religious experience worthy of the name, I've spent a lot of time thinking about religion. I was part of a church for 12 years as a kid, I explored that path again in my 30s when my life had fallen apart, seeing whether there might be something there, something to get me through a divorce, the illness of my father, the commercial failure of my second novel, and some other things.

It didn't take. I went to some Catholic church services with a girl I was pursuing, but it didn't take, and yet between that upbringing, my engagement with writers like Dostoyevsky and Flannery O'Connor, and frankly, just a familiarity with the Bible, and a sense that those were somehow in spite of my self-foundational stories, and finding the message of the gospel, if you read it carefully, and actually listen to what Jesus is saying, finding that not only-- Well, not only did it make sense to me as a set of ethics, it is the foundational ethics for much of Western culture, and we were seeing that when I was growing up in the leadership, the Christian leadership of the civil rights movement, the Christian leadership of the anti-war movement, so it's always been there, and it's been present. At this point in my life, as you say, I'm in my early 60s, I just turned 62, you start to look around for things you haven't gotten into yet.

Interviewer: Then, set out what the ambition for the trilogy is if you fully know it at this point.

Jonathan: In the course of doing some interviews for the book, I've realized that trilogy is maybe not the best word, it calls to mind the Lord of the Rings or something, which is--

Interviewer: Books that you loved, by the way, if I remember right.

Jonathan: Oh, my God, yes. How many times have I read Tolkien? Many, although none of those recently, but you could bind them all as a, "One ring to bind them all," [laughs] one publisher to bind them all. [chuckles] You could bind them all in a single volume, and you wouldn't notice that you are in a new book, and that is not something available to me. I wrote Crossroads to be a freestanding book, and the other two need to be freestanding books.

I do intend to have common characters to take up many of the Hildebrandts later in life, and also to take up their children, maybe in some cases, even their grandchildren. That's what you get when you do a [unintelligible 00:06:03] '50s family story, but so I prefer to think of them as a trio of novels that I'm attempting, with an overarching theme having to do with mythology, with irrational belief, which we're certainly still seeing plenty of in the present, and also with a single-family kind of at the center, but how I'm going to pull that off, I don't know yet.

That's actually-- Painful as it is, that's the place I need to be. I think it's a good place for a writer to be knowing nothing, needing a new idea. I jokingly said to someone a couple of weeks ago, maybe the third of those volumes is going to be a 500 page, single-paragraph stream of consciousness. I've never done that. I was saying it completely joking, I realized that, "Hey, that might be interesting." [chuckles]

Interviewer: It'll take you back to your roots a little bit of the avant-garde. Jonathan, there's been a hell of a lot of discussion, especially, in the last couple of years, three years, whatever it's been, and even longer than that about who can write what, how a White writer can or cannot write about characters of color, men about women, women about men, and I wonder how you engage with that conversation? Can anybody write about anything and anybody, or are there limits to it?

Jonathan: Some years ago, I said something that I'm told was misinterpreted. I think with enough love, you can write about anything, but love is not something I take lightly, love is something that implies deep familiarity, profound connection, and it's rather easy for me to write about fathers, because I have love of a father always to draw on. It's easy for me to write about female characters, generally, because I've experienced beginning with my mother, very powerful love of my mother, and with that love, and part of love is a sense of shared self, an intense concern for what is really happening inside the other person's head, if you've had that experience.

Love is demanding too, you are in fact required to understand what's happening in the other person's head. If you've had that, I think there should be no limit, but that experience of love is not-- You don't have that with everyone, and you don't have them with all groups, so I would never in a million years attempt to do the point of view of a Navajo character. There are some Navajo characters in the book, but they are exclusively seen from the perspective of a White consciousness encountering them, I don't--

Interviewer: You have a scene early in the novel, as I recall, about a White do-gooder in confrontation with a Black woman, and tell me about writing that scene, where this conversation fits in?

Jonathan: I think, in this country, White writers should be very, very careful about how they write about Black characters, and even if you're being rigorous about sticking in a White point of view, you still have to make decisions about how the Black characters come across. I feel as if, obviously, it's incumbent not to traffic in racial stereotypes. It's also important not to err in the other direction, and out of a sense of guilt or deference portray Black characters only as noble and virtuous.

That becomes a conversation in the book, Russ Hildebrandt, the pastor, although completely deplorable in many ways. I think he does have genuine sensitivity about the limits to understanding someone else's culture. He has fallen in love with a younger White parishioner, who he's implacably pursuing, although it could cost him his job. She is the clueless White lady.

For me, the solution to-- It was simply realistic that a White suburban church would have a Southside Chicago urban partner church. That people from the suburbs would be coming in and working there. That happened all the time in the '70s, at least. The way I negotiated that was to give Russ something like a contemporary sensitivity about cultural divides, and then have him play off against somebody who didn't get it.

Really, the effort there was to demonstrate that I'm not unaware of the problem, and that, not by way of virtue signaling, but just to try to make the reader feel less uncomfortable. I don't want readers thinking about anything but the characters. If they start thinking about, "Whoa, the author has waded into this," then I have failed. That's a long answer to your question.

Interviewer: No, not at all. It's hard to have this conversation about a book that you've written, I've read, but it's just out, and therefore, the listeners haven't read, and they're not familiar with the terrain quite yet. There's one thing I think is fair to ask even advance of people having read this novel, is that your work has traveled a long road stylistically.

When you started out in your first couple of novels, they were coming out of a tradition, I don't know what you would call it loosely, but more of avant-garde. There was a very concerted change, certainly, with the corrections and thereafter. I'd argue, even now, it's still changing. There are fewer moments of deliberately hyper conscious bravura descriptions, and yet the characters are shaped by language and language alone in the most vivid and profound ways. I get the sense of a writer that, that is central to his project is this way of going about language. I'd love to know how you think about that.

Jonathan: I do think about it. I think about it a lot. There were many projects in the corrections. One of them was just to show what I could do linguistically. Bravura is a good word. I still enjoy picking up that book and reading a few pages. I say, "Hey, I was pretty good in my 30s" Also, I bump on language that calls attention to itself. Beginning with Freedom, I wanted that not to happen.

I wanted to get out of the way, and to create the same sentence-by-sentence reading experience, where every sentence counts, every sentence is doing something strong, ideally, but to do it with more traditional means I guess. The traditional means are capturing in words, something that a reader might recognize. Particularly, animating sentences with thoughts. If you're pursuing a thought, you actually don't need the bravura vocabulary, spectacular metaphors, all of that stuff, because the thought itself is interesting.

I proceeded in Freedom and Purity to try to become more transparent. Then, finally, with this book where I threw away all of the kind of PoMo high-jinx, and the grand plot elements, and focused on five fairly ordinary characters, certainly in an unexceptional middle-class world. I thought here I might finally, A, really becoming invisible as an authorial presence. Also, not coincidentally, finally writing the book that most clearly represents who I am.

It's really only in the course of writing crossroads that I have said to myself, "What I am is a novelist of character and psychology. I'm not of the avant-garde." I am not of the formalists. Although formal things interest me intensely and are incredibly important, that it's not about formal experimentation. It's certainly not about changing the world through my social commentary. Yes, I'm aware of it. I'm probably too self-aware as a writer. That's my elite college literature study background, with all the theoretical reading I did. I'm super aware, but that's the story.

Interviewer: You said on an interview on French radio recently, and I didn't quite get this, I want you to explain it if you would, that you don't write for the extremists. You write for human beings trying to make sense of things, and make sense of what to do. Who are the extremists, and why don't you write for them?

Jonathan: Who are the extremists? I didn't mean that in a denigrating way, first of all. It's just when I'm imagining someone reading me, I would say somebody who is extremely political, who cannot entertain the idea of a flawed character, but has to jump in with political judgment and condemn that character for the flaws, might be primarily who I had in mind.

Interviewer: Is that a problem in modern reading, do you find?

Jonathan: Oh, it calls to mind an email from a, I think a young man. I have a public email address and somebody wrote to me as the phrase goes, "Writing for a friend, asking for a friend." He said he had a friend, and I believe he said "she", who told him not to read Freedom because it was a tear book filled with objectification of women. I wrote back and said, "You know what? If you're going to hold the characters in literature to a political standard and find the characters not worthy of sympathy, and the author not worthy of reading? You're going to have a very, very sad little list of books you can read."

That has always been, or for a couple of centuries, the project of the novelist, which is to render the full complexity of characters. Moral ambiguity, particularly in the 20th and 21st centuries, that's a central artistic principle. There are people who are so angry and so political that they cannot tolerate the notion that a person can be both good and bad, and that some situations do not have a clear structure of this is right and this wrong. Yes, I think that's the extremism I had in mind.

Interviewer: When you teach or lecture, or meet readers, do you see this as an increasingly dominant strain that people want characters that either, I don't know, justify them, or carry certain political banners in a way that's distorting to reading?

Jonathan: A couple of years ago, you were kind enough to publish a short piece called "What if we Stopped Pretending", that I wrote about climate change, and there was friends with long faces, or who sounded like they had long faces, and their emails to me said, "Oh my God, that was very brave of you. You're the most hated person in environmental circles in the world, and how can you stand to write a piece that gets just slaughtered like that?"

Interviewer: Just to be clear, you got this negative reaction, because you were seen to some degree as fatalistic, is that right?

Jonathan: In my view, I was being realistic about the likelihood that we will solve the problem of climate change, which strikes me as zero likelihood, for good reasons and the data is there for anyone to look at if they care to. Yes, so that was not received well in professional circles, particularly on social media, and it was really weird to hear from these concerned friends, because the response I got was overwhelming, and it was 99% positive.

Those are the people I'm-- The thing is, there are a lot of people out there who want nuance, and who want realism, and who want honesty in nonfiction and in fiction. I would go so far as to argue that it is a silent majority of American readers who want that, but we don't hear from them because they tend not to be hate tweeting, and they don't want to participate in that discourse.

We get the skewed notion of people being unable to read complex texts, being unable to leave their politics behind and entertain ideas that might not be exactly their own. We get that idea, because the minority who reacts that way is so loud, and they have these incredibly compelling platforms for it.

Interviewer: I read in The Wall Street Journal that somebody came to you with the so-called Harper's letter. This was a kind of petition in which a lot of writers and intellectuals signed on to a letter that described an atmosphere in the country in which open dialogue is somehow constricted by what would you say, Jonathan, getting shouted down, and you decided not to sign that Harper's letter? What was your decision based on?

Jonathan: Whether it's a very immediate thing, which was that, I think, I was asked to sign it in June of 2020, and there was just no way, it was not going to be taken as a comment on the protests following the murder of George Floyd, and I just thought it was bad timing that we were in the midst of a renewed reckoning with systemic racism in this country.

Although there are, of course, well-publicized incidences of people who say something seemingly innocuous and lose their job, or are canceled in some fashion, which is to say the Harper's letter didn't come out of nowhere. I felt that it was just terrible timing, that we ought to honor the moment, and also honor the understandable impatience and anger of Black Lives Matter. It was kind of a no-brainer in that sense.

Interviewer: I think with a very broad question, is this a good time to be an American writer?

Jonathan: Well, gosh, is this a good time to be an American writer? I think the argument that the Harper's letter people made was that this atmosphere is having a chilling effect on young writers, that the people are being encouraged to identify what they are politically and stick to the program, and that this is somehow cramping careers, young careers. I have no way to know if that's true. I actually suspect it's not. It's a weak writer who's going to knuckle under, in that sense. I would say, honestly, David, it's a much better time to be an America writer than I would have guessed 25 years ago.

Interviewer: Why do you say that?

Jonathan: Well, in the '90s, when the internet arose and was added to TV and to movies, the three screens, it seemed as if the world of letters would soon be extinct, it would be chamber music.

Interviewer: The attention span argument.

Jonathan: The attention span argument, and the fact that the new technologies really are so designed to be so addictive. It's not just the attention span, but also the attention drain. Not coincidentally, I was writing at a time when my second novel hadn't sold well. I thought, "This must be the end of literature," but I really, really meant it. I really was worried, and it seemed I kind of gave it 10 years.

The fact that the literary world continues to thrive, and I would argue, has become more inclusive and a great way. I think we're hearing from voices of all kinds, particularly people of color and non-male writers, non-cis male writers. I think there's a lot of energy there, and it's like I said, so much better than I would have guessed.

[music]

Interviewer: Crossroads comes out this week. It's the sixth novel by Jonathan Franzen, and you can find some of Jonathan's essays and reporting and more at newyorker.com.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.