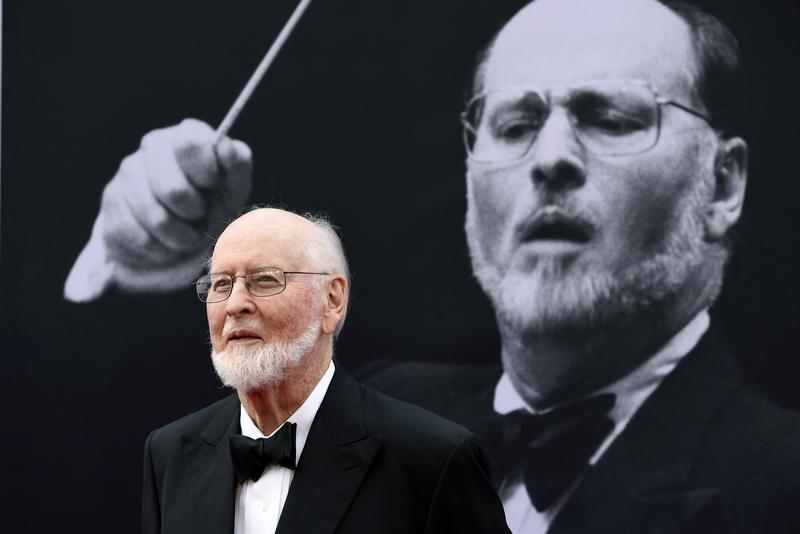

Film Composer John Williams Returns to “Raiders”

David Remnick: Generations of us have grown up listening to John Williams. He's been composing film music for 65 years. That's more than half the history of the cinema. He's got over 100 credits under his belt and five Oscars. But it's not the quantity so much that makes Williams extraordinary, it's the impression that his music makes on us. Whether it's a series, drama or a blockbuster, Williams doesn't just lurk in the background.

MUSIC - Jaws theme music.

David Remnick: Okay, even I know that. I feel a shark circling my feet. That's Jaws. Am I right?

Alex Ross: I think it's actually Ingmar Bergman's Wild Strawberries.

David Remnick: [laughs] All right, so it’s either Jaws or Wild Strawberries. We haven't decided which. The other day, I sat down with The New Yorker's music critic, Alex Ross to talk about the legendary John Williams, and Alex wanted to jog my memory a little bit.

MUSIC - Superman theme music

Alex Ross: I'm thinking one of the many Star Wars films. One of the many Star Wars films? No, it’s actually Superman.

David Remnick: Oh my God.

Alex Ross: It’s a very kind of Strauss Übermensch Zarathustra kind of sound there. But yes, that's also William's in his high '70s Korngold mode.

MUSIC - Raiders of the Lost Ark theme.

David Remnick: That's Raiders Of The Lost Ark. Right? Come on.

Alex Ross: Right, yes. What I love about this is you've got the catchy theme on top, but the thing, you have this stuff underneath in the trombones and timpani, which is somewhat syncopated and just creates this substratum of a different kind of activity, this drum [makes drum beat sounds] and it destabilizes the march aspect of it. This happens in Star Wars too. The themes that everyone remembers are simple enough, but the way he frames them, orchestrates them, fleshes them out is actually very tricky, difficult to play, and just fun to go back to and experience again. You just hear new details popping out of you.

David Remnick: The reason we're talking about John Williams now is because Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is about to come out. That's the fifth Indiana Jones movie and of course, it stars the tireless Harrison Ford. This is probably the last original film score that Williams will write. He said something to that effect recently. Alex, how old is John Williams?

Alex Ross: He's 91.

David Remnick: God bless him.

Alex Ross: But I wouldn't rule it out. He's slightly hedged on whether he's going to ever write another one, and he says that it's hard to say no to Stephen Spielberg.

David Remnick: Let's just stipulate that he's maybe on the back nine of his career. Can you assess for us just to start, his place in the world of film composers?

Alex Ross: He is really the last great living representative of this long tradition of orchestral film scoring that goes back to the Hollywood Golden Age of the 1930s when all these emigrated composers like Max Steiner and Eric Wolfgang Korngold were writing for Hollywood, and he's really the last one. The knowledge that he contains, just of the orchestra, there's no one alive, I think, who knows more about how orchestras work than John Williams does.

David Remnick: As much as or more so than classical composers and conductors?

Alex Ross: I think on a practical level, he knows as much as anyone.

David Remnick: Wow. This is his latest score for Indiana Jones. What about some early examples of his very best work? He started his career headed into the ‘60s, am I right?

Alex Ross: Yes. He originally came out of the jazz world, but he first made his name as an arranger. When he moved into film scoring, he was doing a lot of comedies. His first movie was actually some kind of racecar comedy called Daddy-O. As the years go by, you began to hear, even in some of these early scores a kind of John Williams voice emerging.

David Remnick: Let's talk about that. You've got a score to one of the more emblematic movies for him early on, and that's How to Steal a Million, which starred Audrey Hepburn and Peter O'Toole, and it came out in 1966.

MUSIC - How to Steal a Million theme.

Alex Ross: This is one of William Wyler's last movies. It was on TCM and I was half watching it. The credits were going by and I didn't see the name of the composer. I was about to go on Google and look up the composer when something happened in the music and I knew. These little quick sculling brass figures and it was just totally John Williams. This is the same kind of just very agile, active, brilliant kind of music that you hear in Star Wars and a lot of other cues. I think about the fact that Schubert, when someone's telling Schubert about a new musician, composer on the scene, Schubert would ask, "[German language]? What can he do? What's he got?'

John Williams has it. He can do anything. Any style that you throw at him, any cinematic situation that you put him in, he can cope with. It's just an incredibly diverse group of scores. He was also doing disaster movies like Towering Inferno into the '70s, Towering Inferno, Black Sunday, Earthquake, and a personal favorite of mine, The Poseidon Adventure.

David Remnick: The best.

MUSIC - The Poseidon Adventure

David Remnick: Something bad is going to happen, something horrible.

Alex Ross: It's also rather grand and romantic.

David Remnick: That’s right.

Alex Ross: It has a kind of slightly William Walton British feeling to it. He really elevates these pretty kitchie, although lovable movies, these disaster movies with the nobility that he can't help bringing it to bear. It's never bombastic either because he doesn't pile it on. His orchestration is actually very clear and lucid. It's not heavy romantic stuff, and so it dances around the images on the screen and in a great way.

David Remnick: You're a teensy bit younger than I, but not tons. We've been going to concerts together for a long time with The New Yorker. We're talking about music for a long time. When we first started, I would not have guessed because your tastes are pretty highbrow, even when it crosses over into rock and roll. I would not have guessed you were a fan of John Williams. Was I being unfair?

Alex Ross: I've had a slightly checkered journey, history with appreciating John Williams over the years because I was a kid when these classical movies came out in the mid-late '70s, Star Wars, Close Encounters, Raiders Of The Lost Ark and Empire Strikes Back, huge events for a 12-year-old kid, even one as weird as I was. I was especially obsessed by Close Encounters, the movie and the score.

David Remnick: It plays an incredibly important role in the film.

MUSIC - Close Encounters theme.

Alex Ross: There it is. There it is. Yes, so this is the theme that he wrote for the communication between the people on the ground there that station at Devil's Tower and the spaceship, the aliens when they land. The music is a dramatic player in the narrative.

David Remnick: Was it just in the script, “Insert theme from John Williams here, figure out later,” or how did it work?

Alex Ross: He came up with the theme. There was an idea that there had to be some simple, recognizable theme that could blast through space and reach the aliens and serve as the language of communication. I went to visit him not long ago, and he showed me the original score for Close Encounters, which reduced me to slack-jawed nine-year-old self. He writes everything out. There's this tremendous moment later on where the human keyboard player gets onto this crazy duet with the spaceship.

David Remnick: And it's faster and faster.

Alex Ross: Yes, intensely contrapuntal and dissonant.

MUSIC - Close Encounters.

Alex Ross: In the score he showed me, he wrote it all out. But the amazing thing was there's also a piece of paper slipped into the middle of this score and it was an array of, I don't know, 12 or 14 different attempts at that five-note theme. He told me, “I haven't seen this in a long time,” and he was looking at them and humming a few of them. [laughs] It was funny because some of them just didn't seem to work at all.

David Remnick: It's like Beethoven going, “Da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da.”

Alex Ross: Yes, exactly. Yes. Some would just be these little squiggles like, ah, that wouldn't have worked at all. Then toward the bottom, there was the five-note one that we know and it was circled. What he told me in general was that it just takes a tremendous amount of work to come up with these themes. They need to be short, they need to be memorable, they need to kind of cut through the mayhem of these action and sci-fi movies with this just kind of storm of noise happening all around.

And I think this is very important for his compositional process, they need to be malleable, because he doesn't just plop the theme out and leave it at that. His scores are this kind of very complex string of variations on these little motifs. Then when you go over the whole Star Wars cycle over nine films, it's a massive series of variations on these light motifs.

David Remnick: One of the things that you like about him is this, what you call an old Hollywood scoring technique. You've made reference to the 1942 film King's Row, which starred a former president if I'm not mistaken, and that was scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Let's listen to that and maybe try to relate it to John Williams.

MUSIC - King’s Row.

David Remnick: Fantastic.

Alex Ross: You can hear where Star Wars-

David Remnick: Sure.

Alex Ross: -comes from. When Williams went to George Lucas on Spielberg's recommendation, Lucas supposedly was planning to issue the film with a lot of classical selections imposed in the picture the way Kubrick did with 2001. John Williams went to Lucas and said like, "I can do all this for you. I can write new music that echoes the kind of old-fashioned Hollywood afternoon serial adventure kind of atmosphere." I think Williams deliberately looked at these scores, learned from them. There is a family resemblance between that Korngold theme and the Star Wars theme.

David Remnick: Absolutely.

Alex Ross: There's a fifth and then it goes down a couple of steps. It's pretty amazing that this body of music exists. There's nothing quite like in a music history, a composer working on a-- not even Wagner wrote a cycle of nine works spanning 40 years.

David Remnick: Has there ever been in the history of cinema, a director-composer collaboration that even approaches the Spielberg-John Williams relationship?

Alex Ross: Oh, no, definitely not. I mean there were sustained relationships between Hitchcock and Bernard Hermann. I think Takemitsu had great relationships in Japanese cinema, but this has gone on for almost 50 years, almost 30 movies with Spielberg going back to Sugarland Express in 1974-

David Remnick: That's his first feature.

Alex Ross: -I think it was. Yes.

David Remnick: Alex, what should we go out on? You want to pick something maybe a little lesser known from this gigantic body of work?

Alex Ross: I think I might choose a score which is atypical of the most familiar John Williams style, which is music he wrote for Robert Altman's Images. It's somewhat dissonant or off-center in terms of the musical language, but it also has its lyrical side.

MUSIC - Images.

Alex Ross: He actually brought up the score as one of his favorites and signified for him the kind of career he might have had if he hadn't gone into film music at all, but gone into the concert music arena. I think when you step back, you might see that this whole body of work really hangs together. It is all one personality appearing through different media and in different styles. That's probably more and more how we're going to think of John Williams as the years go by.

David Remnick: Alex Ross, thanks so much.

Alex Ross: Thanks so much, David.

MUSIC - Images.

David Remnick: The New Yorker’s Alex Ross talking about the work of John Williams. Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny with Williams's score comes out next week. Alex's books about classical music include The Rest Is Noise and Wagnerism.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.