David Remnick: Do you feel like people are too easily offended these days?

Respondent: Oh, that's a loaded question.

Respondent: Yes,

Respondent: No, I don't.

Respondent: Oh, Jesus Christ. Compared to what, all of human history?

David: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. We're talking today about free speech and threats to free speech in many forms. That includes so-called cancel culture, what it is, and whether it even exists.

Respondent: That's a great question. The answer in my opinion is, absolutely.

Respondent: I don't know. I think the word cancel is oversaturated and I just don't like that term.

Respondent: I think most Americans don't think about this.

Respondent: I hate it. I hate people getting canceled and I think there're always a couple of sides and you can always catch people on a bad day.

Respondent: That being said, you deserve what happens to if you're a shit bag.

David: Now, these are questions I think a lot of people have been thinking about lately, myself included. I was struck recently by an article in a journal called Liberties by William Deresiewicz who taught at Yale and then at Scripps College in California. The article is called 'Birthrights' and it talks about the author's upbringing, which was in an Orthodox Jewish community in New Jersey.

William Deresiewicz: I grew up in a world that was divided as if by a thick black line down the middle of it, between us and them. Us was the Jews, them was the Goyim. The understanding was that there was an eternal fixed enmity between the groups that the Goyim were ineradicably other, that they were alien, that they were hostile, that we were better than them, and that it was necessary to remain always within the group and to live by the norms that the group dictated in order, well, to be safe, but also just to live the life that was appropriate for you.

I think this is common among people who grow up in groups that are that self-enclosed and especially groups that are that embattled, as the Jews have felt embattled historically. I don't think groups are evil. I don't think that you can't be an individual and be a member of a group at the same time, but groups often make extraordinary and, I would say, excessive claims on their members in ways that prevent them from developing as individuals.

David: When William Deresiewicz looks at college campuses now, he sees a kind of us versus them thinking pervading students' lives, a concern, maybe an over-concern with identity versus individuality. That, he says, affects the way students talk and write, and ultimately, how they go about learning. You've spent a lot of your life in academia as a student, then as a graduate student, then as a professor. Was there a moment when you felt like the rules around free speech started to change? What was it like before and what was the change?

William: Well, actually that change happened after I left academia in 2008, but I did go back in 2015 to teach a course at an elite liberal arts college.

David: Scripps College in California?

William: Right. In one of the Claremont colleges. It was clear-- I think maybe being away for that many years enabled me to see the situation more clearly because it was radically different. The first thing was that the person who had brought me there, who was the head of the writing center and who was very militant in the new speech codes, for lack of a better word, told me, "You're not supposed to say 'crazy' anymore."

You can't say 'crazy' anymore because it stigmatizes the mentally ill. She had a lot of other strictures as well. Then, once I met my students and started to talk to them in my office, they, without me soliciting this information, because I really still wasn't aware of what the climate was, started to tell me how afraid they were really to say anything, because they didn't know if they were going to say something that you weren't supposed to say anymore.

A student of mine, I think she wrote on a paper, that she was surprised to learn that a fellow student had been very close friends with her for three years now-- she was a junior-- was religious, and was not only religious, but went to church every Sunday. My student said, "Why didn't I know this yet?" Her friend said, "Because I don't feel comfortable being out as a religious person at Scripps."

David: The university that you were at for a long time, Yale University, a long time ago, generations ago, had a young undergraduate and then graduate named William F. Buckley who came along and wrote a book called God and Man at Yale. His argument sounds a little bit similar to what you're saying, is that there was a liberal consensus at Yale. It dominated the students, it dominated the faculty and conservatism was impossible. It was impossible to be a conservative Yale. This is decades and decades ago. What's change?

William: Well, it may be that some things haven't changed, or certainly that this is a recurring problem. In fact, I don't think I was even aware of this, but when I was at college, surveys showed that conservative students actually slightly outnumbered liberals, but both were far outnumbered by moderate students. This was early Reagan. It goes back and forth. It's, let's say, a perennially recurring problem on college campuses. I think right now we're at an especially bad point.

David: Is part of it also a reaction to the politics, the national politics that we've seen after the Obama era with the ascendance of Trump?

William: Oh, there's no question that part of what's changed is Donald Trump. There's no question that Donald Trump and his movement embodies evil forces in American society, a recrudescence of evil forces and that a vigorous response must be made. The question is, what is that response going to be? Is it going to be the enforcement of a progressive orthodoxy, or is it going to be what colleges are supposed to do, which is to help students think better? Not what to think, but how to think.

David: When you look at so-called cancel culture on social media, some argue it's effectively limiting people's free speech, but others argue it's just the opposite. It's democratization of expression. Aren't students who protest college speakers just engaging in free speech themselves?

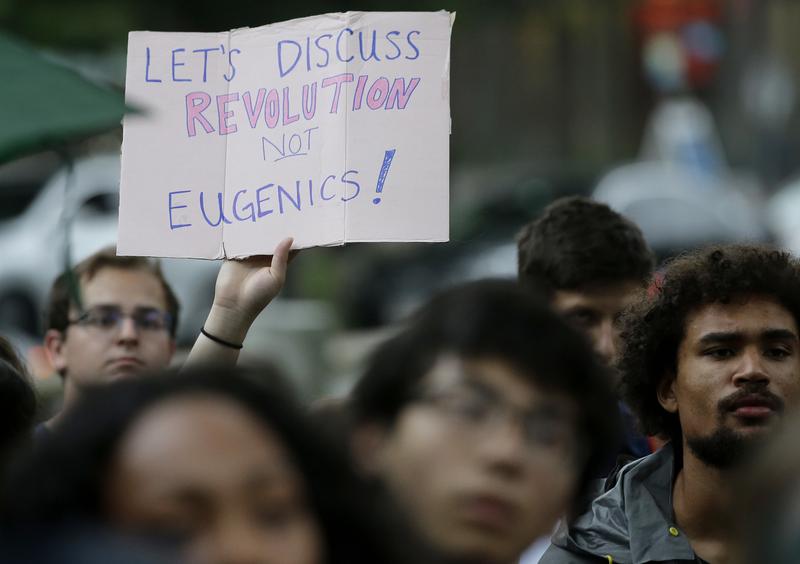

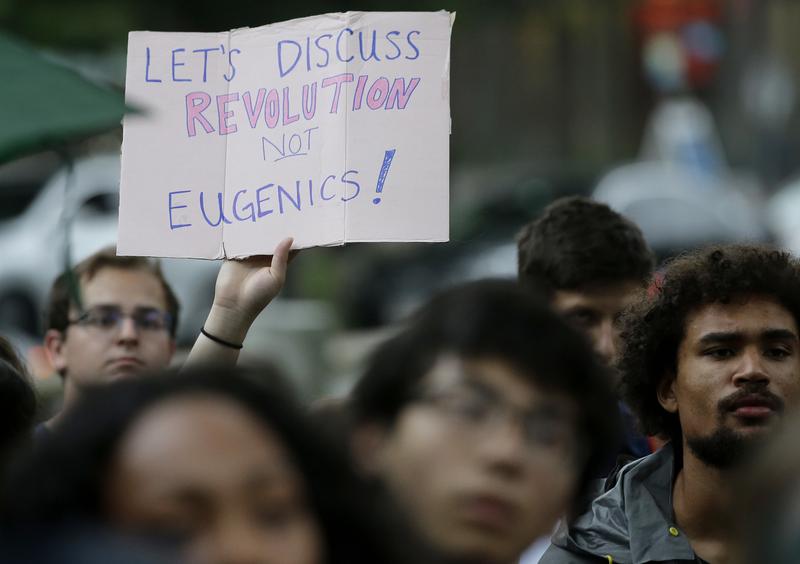

William: When somebody you don't like comes and speaks on campus and you picket outside and you protest or you organize a teach-in in opposition to their views, that's more speech. That's great. When you blockade the building and don't let people in, or when you flood the auditorium and then get up and march out or shout them down, that is speech or symbolic speech used to limit speech.

David: You and others have argued that the left is making academia inhospitable to certain ideas. At the same time on the right, there's a movement to limit what can be taught in classrooms. I'm thinking right now about the movement to ban critical race theory and certain perspectives on American history. Are there similarities, do you see, between these two currents?

William: Yes, absolutely. When one side says that we need to limit what teachers can say, then the other side is going to feel greater license to do the same.

David: William Deresiewicz is a writer based in Oregon.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.