Talking to Conservatives About Climate Change: The Congressional Climate Caucus

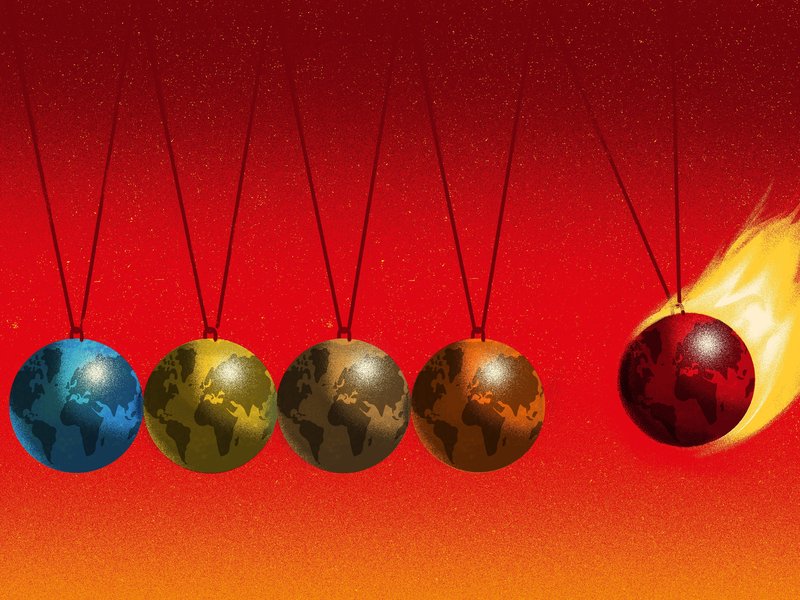

David Remnick: With the record-breaking heat of this summer, record after record after record. We didn't need any more evidence of the appalling consequences of climate change. Now we have the tragedy on the island of Maui in Hawaii, a rainy state that rarely had wildfires until recently. The question on a lot of minds is this, will this hottest summer in recorded history be a wake-up call, an opportunity to put aside some of the partisan fighting and begin at last to face the reality as frightening as it is? Or are we just going to keep sleepwalking, to further self-immolation?

I'm joined now by a leader of the Conservative Climate Caucus, a group of about 80 Republicans in Congress. Iowa Representative Mariannette Miller-Meeks who was elected in 2020. She's an army veteran, a physician, and she formerly ran the Iowa Department of Public Health. Miller-Meeks serves as vice chair of the Conservative Climate Caucus. Now, the leading presidential candidates in the Republican Party tend to downplay the climate crisis if they refer to it all, certainly on the national level.

On the campaign trail, Donald Trump has said climate change might affect us in 300 years. He used to say that it was part of a Chinese hoax. Ron DeSantis has said we're politicizing the weather. How do you feel about that? Are they wrong? What are you doing to get top members of your party to care more about the climate issue?

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: One of the reasons I started speaking on the issue in 2017 and 2018 was because I didn't think Republicans were engaged enough in the conversation. I thought that we had not been involved. I can't control what the presidential candidates say.

Interviewer: I guess what I'm asking is, "Do they disappoint you by their lack of urgency?"

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: No. Again, I'm a member of Congress, and we're trying to work on bipartisan solutions. I think perhaps where there's a difference among individuals is with what urgency people believe there needs to be change. I believe that having rapid change without having affordable, available energy is not a solution. We're trying to bring some pragmatic sense to the discussion of climate, environment, and energy. Our mission is to advance, I think, common sense solutions that allow our economy to grow, allow our economy to strengthen, and compete globally around the world, but that are common sense solutions that afford us.

We have to have affordable energy. Energy demand is going up. It is not going down. It's going on.

Interviewer: I hear you say repeatedly the phrase common sense. No one's against common sense. It's hard to argue against common sense. Let's get that out on the table. Can you explain what the conservative approach to climate policy is, and how does it differ from what we might hear from the Democrats?

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: I don't think there's a vast consensus on what's common sense policy is. Hydropower, clean energy. To me, it would be clean energy, but yet you have a state, Washington state that's trying to shut down their hydroelectric dams along the Snake River, but yet it would be clean energy. Iowa is a state where 50% of its energy is from renewables. Now almost 60% of our electricity is from wind. We are a net exporter of energy. We've done all of that without mandates or without emission standards.

I haven't heard my colleagues on the other side of the aisle until recently talk about nuclear energy.

Interviewer: A lot of people, Democrats, and others, have changed their minds about nuclear energy. Despite the risks, you support it?

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: I think if you're trying to electrify an economy and reduce emissions, first and foremost, every energy generation source should have a lifecycle carbon analysis. Things that may be without emissions when they produce electricity may have a significant carbon footprint through their production to their disposal, first and foremost. Secondly, I understand the fear of nuclear, but I also think that the fear, in some ways, was unwarranted. Like many people, we saw what happened at Three Mile Island. Were there any deaths that occurred there?

Interviewer: They sure were at Chernobyl.

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: Chernobyl, yes.

Interviewer: And Fukushima.

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: At Chernobyl, it was bad reactor design. Didn't have the right coolants. We have a nuclear power plant in Iowa, Duane Arnold nuclear power plant in Palo. Even in 2008, when we had the massive flooding that flooded downtown Cedar Rapids, the Duane Arnold nuclear power plant was a source of electricity for the eastern part of our state. Was never flooded, was an excellent facility, well managed, well done. What we're seeing with the small modular reactors, number one, that they're safer.

We certainly have other countries that have a track record, a great track record. I think nuclear is certainly an option. It's unfortunate that the Biden administration has taken offline land near the Grand Canyon, which is a source of a lot of high-grade uranium for this country so that we can mine our own uranium. How can you have domestic energy production if you're not allowing mining? If you want to have an electric grid, because you need to have longer power lines in order to take wind or solar energy from one area of the country to another area of the country, you need copper.

The Duluth copper mine in Duluth, Minnesota has been trying to get permitted for over a decade. You have an Inflation Reduction Act, which on one hand says you need to domestically support source minerals, but yet we won't allow permitting. Permitting reform, liability reform when it comes to energy production, those are things both Republicans and Democrats agree need to happen to allow us to be able to have a cleaner energy future. Our mining practices are more environmentally friendly than the mining practice is in China.

Do you know how much earth you have to move in order to get the rare earth elements? Do you know how many children read cobalt red, which is akin to blood diamonds, about children that are put into mining Cobalt? I think those things--

Interviewer: I can't disagree with that.

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: Those things have to be brought into consideration too.

Interviewer: Congresswoman, the Inflation Reduction Act was the most significant climate legislation ever passed in the United States. Why do you oppose it?

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: I think there were pushes toward such as when the EPA puts forward its guidance on tailpipe emissions, such that it's pushing to have electric vehicles to be 67% of vehicles on the road within about eight years. Those policies that mandate and takeaway choice are not policies I could agree with. Had they been individual bills, had we been involved, I think you would have seen that there would have been more participation and more bipartisan support.

Interviewer: Let me ask you this. The fossil fuel industry gives campaign donations at some very high multiple to Republicans and some Democrats, like Joe Manchin, far more than Democrats. Do you think the fossil fuel industry puts its thumb on the political game in such a way that it influences things for the worse?

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: Do radical environmentalists put their thumb on and influence politicians on the Democrat side?

Interviewer: Are you going to compare the fundraising of radical environmentalists to the fossils to Mobil and ExxonMobil?

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: My viewpoint on carbon-based fuels and liquid fuels would be as it is now, based upon the research I've done, regardless.

Interviewer: Congresswoman, when you talk about climate change with your constituents, what's the conversation like? I just want to get a sense of what that back-and-forth is like.

Mariannette Miller-Meeks: I talk to my constituents the same way I talk to you. I had a town hall last night in Iowa City, where the University of Iowa is. It's a county that votes about 80% Democrat. The majority of people who attended were Democrats. The Citizens' Climate Lobby was there. They had several questions. They appreciate the fact that I've gone to both Cop 26. Cop 27. I will be going again this year. I'm glad to see that the International Panel on Climate Change has finally recognized American agricultural's contribution to reducing emissions.

We have farmers in our state that are doing truly amazing, groundbreaking things, young farmers that are doing sustainable regenerative agriculture and training other farmers how to do it, mentoring them. I don't try to scare people or frighten people or lead them to believe that the world is coming to an end. If we don't adopt policies which I know are going to lead to a lack of electricity, a lack of heating and cooling, a lack of an ability to drive your vehicle to work, lack of the ability to recreate and lead to higher energy prices and less energy.

Interviewer: I guess what people would say who respectfully disagree with you from the other side of the aisle is that you talk about what's realistic. Given what we know about the destructiveness of climate change, the deaths, the property damage, the cost of rebuilding after disasters, that a gradualist, incrementalist approach like you are describing, however well-intentioned is in fact not realistic. That's the argument.

Marionette Miller-Meeks: I understand your position, but I'd respectfully disagree. Isn't it important that people are able to drive from a job to a job? Isn't it okay for people to live in a rural area? Are we going to be able to have farmers be able to farm? I'm in an area where it has the highest unemployment and the lowest wages of the state, and you're going to tell me that I should be okay with $4 gasoline because you want an electric vehicle on the road. I reject that premise. My job is to look out for my district and my state.

How do we lower emissions while allowing the United States to compete economically around the globe? If your narrative is that the world is going to end, I think we were going to end in 10 or 12 years, and we're now six years into it. Every time someone advances a narrative that it's a crisis if we don't do something now. I think Al Gore said that what we were going to have no Antarctica and no Arctic by 2013.

Interviewer: The year might be off by this or that, but our Antarctic ice is plunging into the ocean. We see it on film. This is not some made-up narrative.

Marionette Miller-Meeks: I didn't say it was a made-up narrative, sir. I just said that every time we advance that there is a crisis and there's doom, and it doesn't materialize, scientists, and we as political leaders, and people who are advancing policy, lose credibility.

Interviewer: Congresswoman Miller-Meeks, thank you so much. I appreciate your time.

Marionette Miller-Meeks: You're so welcome. Thank you very much.

[music]

Interviewer: Marionette Miller-Meeks is vice-chair of the Conservative Climate Caucus, and she represents Iowa's first congressional district.

[00:12:04] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.