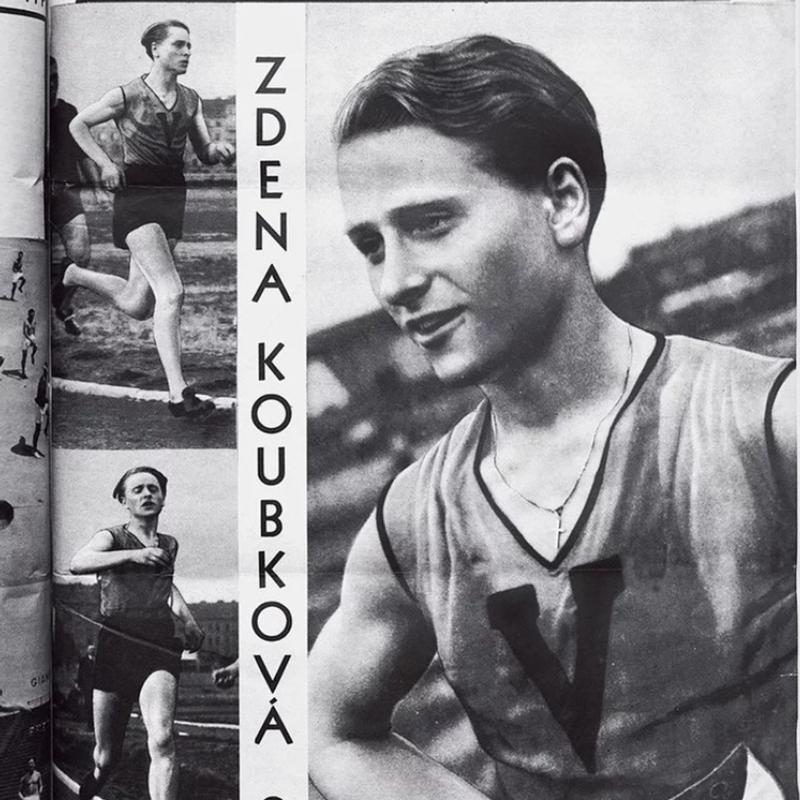

The Trans Athletes Who Changed the Olympics—in 1936

Host: In 1934, Zdeněk Koubek, a track star from Czechoslovakia, set the women's world record for the 800-meter dash. A year later, Koubek shocked the world by declaring that he was now living as a man, an announcement that gained him international celebrity. He eventually gave back the medals that he'd won in women's competitions.

Speaker 2: [foreign language] Well, he's going to work now in the French casino, you see? Then, he'll start the game maybe like a athlete, you see?

Speaker 3: He's going to train and compete against men?

Speaker 2: Yes. That's it.

[music]

Host: Around the same time, a popular British track star who held titles in women's competitions also transitioned. Both these stories contributed to panic over trans athletes, and remember, this was all the way back in the 1930s. These stories also led to sex testing policies that still define sports today.

That's the subject of a new book by Michael Waters called The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports. Michael Waters has written for The New Yorker and other magazines. He talked about the other Olympians with our sports columnist Louisa Thomas.

[music]

Louisa Thomas: Can you tell us a little bit about Zdeněk Koubek?

Michael Waters: Yes. Koubek is born in 1913 and what would eventually become Czechoslovakia. He's born before World War I, before it becomes independent, and the capstone of his career is in 1934 when he participates in something called the Women's World Games, which for just a slight bit of context, basically, the early Olympics had incredibly few sports for women, and track and field sports for women in particular was stigmatized.

The Women's World Games was actually the highest level of competition for someone like Koubek, especially for the Women's 800 Meters, which was his main sport. In 1934, the Women's World Games is in London, and he both wins gold and sets a world record. That puts him on the map, and then really what catapults him to fame ultimately is a year later in December 1935, when he does decide to transition.

Louisa Thomas: We're talking about gender here, it was using that word gender-- I mean, in the book you used the word sex as opposed to gender, and I was just wondering if you could explain that decision a little bit.

Michael Waters: Yes. It's a tricky thing to talk about. I definitely wrestled with it, still wrestle with it, but essentially, at the time in the 1930s, there was no concept of gender and sex as distinct things. Today, we think of gender as this psychological socialized identity, and sex as this assigned identity roughly based on physical traits of some kind. It's an imperfect assignment, but that's what it is. In the 1930s when people were talking about transitioning, they were only talking about sex.

Louisa Thomas: What was the media coverage like when he announced this transition?

Michael Waters: It was pretty sensational, but I really think through all of this reporting, what you see is this genuine sense of curiosity about Koubek, and about what it means to transition gender, and so, pretty quickly, after the initial wave of coverage, you have different sexologists and scientists of different kinds, doctors writing into magazines, including some really prominent sports magazines of the era, describing what this means and what it means to move between these categories, which I'm calling gender transition, but they would say something about sexual metamorphosis, which doesn't really translate to us today.

I think through it all, you see-- For all of the boldfaced headlines that feel a little ridiculous in retrospect, you see this genuine-- just interest and intrigue about Koubek and what he meant for what they were calling sex and the possibilities of sex. It really was an era in which there seemed like such potential for sex and gender as we would describe it today.

Louisa Thomas: Obviously, in 1935, 1936, especially in the sporting world, but also [chuckles] in the broader world, these are loaded years. What else was happening? The newspapers were also full of news of the rise of fascism. Could you talk a little bit about how Koubek fit into that story as well?

Michael Waters: Yes. In 1935, the biggest sports story is not Koubek but is rather the Berlin Olympics, which are happening the following year in the summer of 1936.

Speaker 6: Berlin's great day dawns with the arrival of the Olympic flame at the end of its 2,000-mile journey from Greece. Meanwhile, a packed stadium and flag-draped cheering streets greet Chancellor Hitler on his way to perform the opening ceremony.

Michael Waters: The Berlin Olympics, I think today are quite famous, but they are especially famous because they were hosted in Nazi Germany. In 1935, a lot of the coverage in the US around the Olympics was talking about this really intense boycott movement that was happening where a bunch of American athletes and officials and activists were saying we shouldn't glorify the Nazis in this way. We shouldn't give them this platform through which to showcase their power and ideology in the form of the Olympics.

This is an era in which fascism is rising throughout Europe. You see it really directly trickle down into the sports world. While the public, as we're describing, was quite receptive to Koubek, I think this is an era of fascism in Europe, and you start to see that in how actually policy gets crafted in response to him.

Louisa Thomas: There seems to be a disconnect between the public responses to these transitioning athletes. How did the sporting world respond?

Michael Waters: Ultimately, what happens is that a small group of sporting officials have this backlash to him, and they see the story of Koubek transitioning gender, and they say that it is a harbinger of things to come in sports and that there has to be policy instituted. I should say for context also, Koubek only wanted to play men's sports. Koubek was like, "I just want to play with other men." It was like a false conflation in the first place that these sports officials were making.

Louisa Thomas: Right. It's a bit confusing because Koubek's transition-- What he inspired was actually a fear that men were disguising themselves as women and competing in women's sports in order to win, and so this policy that we're going to talk about, it wasn't originally aimed at trans athletes.

Michael Waters: Yes. Absolutely. Ultimately, what happens is that the IAAF, the track and field organizing body in August 1936 at the Berlin Olympics passes this early, really rudimentary form of sex testing. The policy is very vaguely worded as a lot of reporters actually did note at the time. The IAAF couches sex testing in this first form under its protest rule. Basically, what it says is that if a competitor wants to lodge a protest against another athlete--

There's this vague allusion to something doubtful about their bodies or something. They describe it as "abnormal women athletes." If a competitor wants to lodge a protest against a fellow athlete, they can, and then a doctor would physically inspect that athlete. They didn't define what the doctor was looking for. They didn't define who would qualify as being allowed to participate in women's sports.

I mean, it really seemed to be a policy of, "Oh, we'll know it when we see it," but yes. This first form of sex testing was basically an athlete could say, "This person who beat me, I have questions about," and then that person would be subjected to kind of like a strip search, a really gross physical examination. The IAAF at the time didn't even spell out what they would be looking for and who would qualify.

Louisa Thomas: Right. It's like this person has what? Hairy legs or muscular arms? I mean, that's-- [chuckles]

Michael Waters: Yes. No. For sure. In this era, you see lots of fear-mongering and panic around just cis women who looked masculine, who had big biceps, or there was this American sprinter named Helen Stephens, who had a deep voice because of a childhood accident, who was constantly a subject of these rumors and fearmongering about sex testing, and so-- Someone like that could be caught up in this, too. There wasn't really clear policy. It was just anyone who didn't fit this very normative idea of femininity in the first place.

For further context, this is an era, too, when there's so much fearmongering about just women playing sports and especially playing track and field in the first place, and so masculine women, in general, were just subject to scrutiny and critique. Then essentially what happens is that sex testing expands and you first start to see letters back and forth from the IAAF in 1939 calling for the sex testing of all women in women's sports.

Then after World War II, essentially, all women are required to showcase a medical certificate proving that they had gotten some kind of gynecological exam that "proved" that they were a woman or they fit this definition created by the IAAF.

Later in the century, you could be randomly tested by the IOC, but the idea was that this wouldn't be testing just based on a protest from a fellow athlete, but this was the default of anyone who wanted to compete in the women's category had to undergo some form of testing, or had the threat of testing. Today, all women athletes are governed by these rules, but only certain women end up to be tested.

As we talk about sex testing today, we often are forgetting where these policies come from in the first place, that they are the result of the Berlin Olympics in 1936, and they are the result of these very specific officials who were certainly swayed by certain fascist ideas, and just that history of where these policies even came from in the first place has largely been forgotten.

Louisa Thomas: Let me ask you about Koubek. Koubek transitions, what happens to him?

Michael Waters: Yes. In 1936, a few months after Koubek first announces that he's living as a man, he becomes a global celebrity, and a producer on Broadway, in New York, reaches out to him, and asks him to come to New York to perform in this variety show that he's putting on.

In August 1936, as this discussion is happening in Berlin around sex testing policy, Koubek is taking the steamship from Czechoslovakia to New York, and then he has this weird perfunctory role in this Broadway show for a couple of months in New York. Then after that, he goes to Paris to perform in this variety show where he danced alongside Josephine Baker. He's this global celebrity for this moment in 1936.

He eventually gets a driver's license that identifies him as a man, and shortly thereafter, he gets married to a woman. This is an era in which the far right is rising in Czechoslovakia. The Nazis eventually take over. Koubek, I think, by nature of having these documents that identify him as a man and by nature of just receding from the spotlight, he ultimately does survive this fascist era in which many other queer and trans people are being sent to death camps and having these really extreme interventions by the Nazis.

Then in 1944, he enrolls in this local team, and for the first time gets to play in men's sports. He seemed to do it for a number of years throughout his life. It's really this conclusion to his story that he gets to do what he always wanted, and he's doing it above all else for just the love of competition in the first place.

Louisa Thomas: The discussion around sex and the Olympics and sex segregation in elite sports and elementary school sports obviously is a major culture war front today. No longer are athletes required to do a strip test, but how is that category defined right now?

Michael Waters: Yes. Really what you saw since the 1930s is after all these strip tests got a lot of criticism, you see sports officials and the IOC eventually move into chromosome testing, with the idea that we can see who has the right chromosomes. You see that happen in the 1960s and then that got a lot of criticism from athletes themselves, from other officials, from doctors who were talking about how chromosomes, even themselves don't neatly map onto sex. You can have a mosaic of chromosomes and not identify as intersex, for instance.

After all of that criticism, eventually, the IOC moved to this hormone-based testing, which similarly, there's not like a cutoff between when a hormone level switches from female to male or something like that. There is this spectrum of hormone levels regardless of who you are.

Today, most recently, what has happened is that now the IOC doesn't set an overarching policy, and so, it's up to these individual sports federations, like World Athletics, to set their own policies. It's kind of this haphazard slapdash set of policies that are quite punitive to especially trans-feminine and intersex women in sports. Of course, what is lost in all of this discussion is just the human toll and just the lack of respect for these really successful trans and intersex athletes themselves, who have just become these political pawns, and who just want to play their sport.

Louisa Thomas: There's a book that you cite at the end of yours, by Katie Barnes, Fair Play, which I think does a pretty good job of laying out some of these-- the evolution of the understanding of some of these debates around trans people in sports. They basically described sex as the result of the interplay of chromosomes, sex hormones, internal reproductive structure, gonads, external genitalia, being this very complex thing, and yet, it is complicated because certainly among elite athletes, there is a demonstrated effect of going through testosterone-driven puberty. Times in men's events at the elite level tend to be 10% to 12% faster in track, let's say, or in swimming, than in women's events.

I think that part of what makes it complicated for even people who are sympathetic to the fact that there is this human element that want to see trans people just play their sport, and willing to admit that the categories are complex and more complex than our current conversation allows. Yes. There is just a demonstrated effect like the times are what they are. I'm wondering what you think of that.

Michael Waters: Yes. It's a complicated subject that I don't think that l, as a historian, want to be the one ultimately trying to litigate. I think to me, what is striking about reading the contemporary policies is the fearmongering that has been focused on these trans women and intersex women in sports. If you are a successful transwoman athlete, you can't play in most of these Olympic sports. You can't play in the sport that corresponds with your identity.

Louisa Thomas: One of the things that's so striking to me is that a lot of the policies, certainly in the United States, are actually not targeted at Olympic athletes. We're talking about children often. Barnes's book, for instance, Fair Play, is not any kind of structured as an argument, but at the end, they do say, "Well, here's my opinion," and they say, "Maybe we should end sex segregation," for elementary school, let's say, while acknowledging perhaps some restriction at the elite level is appropriate. They made it very clear that there should be a path toward inclusion and that not only should trans people be allowed to compete, but they should be allowed to win, which is a lot of-- A lot of people have no problem with trans people competing as long as they're finishing last. [chuckles] The question arises when they start to win.

Michael Waters: All of these other invisible advantages that we don't talk about in sports, like, class, for instance, just having the money to afford trainings in the first place, has such a strong correlation with their level of success in these competitions. That's something that we're not regulating. We've accepted that there's these advantages. There are all kind of physical advantages around heights, et cetera, et cetera, that we don't try to regulate in this way.

I hope that even just by seeing where these policies come from in the first place maybe allows us to add some nuance to this conversation, too, and see that sex testing itself is a very subjective policy that was created in a very specific moment, and maybe doesn't have to be inevitable in sports, at least in the way that it's structured currently.

Louisa Thomas: Thank you so much for joining us today.

Michael Waters: Thank you for having me.

[music]

Host: Michael Waters is the author of The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports, which comes out next week. Louisa Thomas writes our column The Sporting Scene at newyorker.com, and she'll be joining us soon to talk about the upcoming Olympics.

[music]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.