“No Other Land”: The Collective Behind the Oscar-Nominated Documentary

David Remnick: In a week of astonishing headlines, maybe nothing was more astonishing than Donald Trump's proposal that the United States take over Gaza, ethnically cleanse the region of Palestinians, permanently exiling a population already traumatized by war, and then turn the whole thing into what Trump calls the Riviera of the Middle East. Was this a serious proposal? It certainly put a smile on the face of Benjamin Netanyahu, who's not only intent on obliterating Hamas in Gaza, but at the same time making Israel's control of the West Bank irreversible.

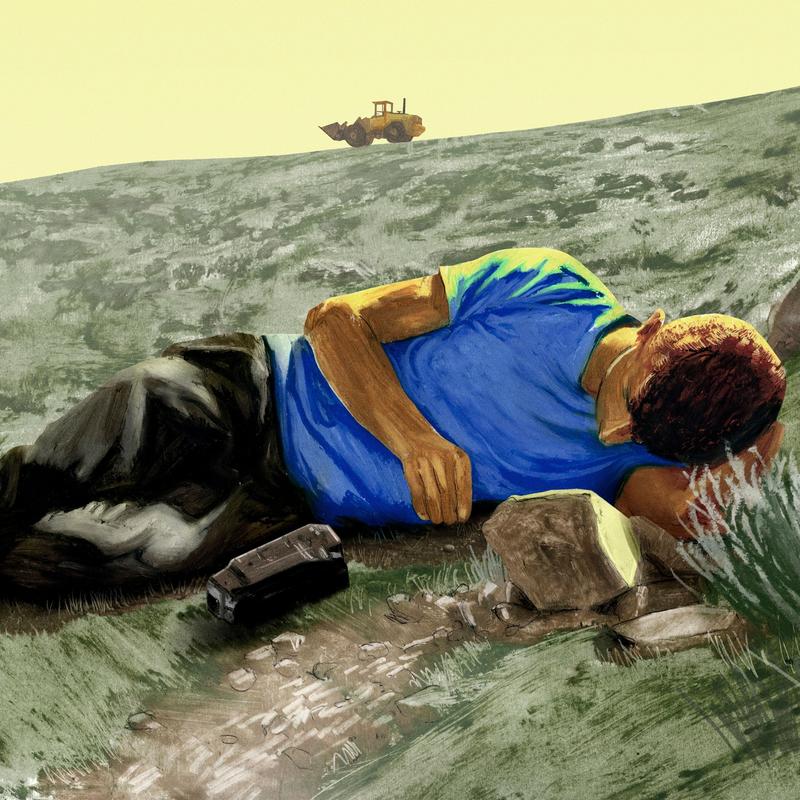

Even if Trump's proposal was merely part of his strategy of flooding the zone, the reality is no less troubling. To understand what that reality is, particularly in the West Bank, there's a new documentary film that you should see called No Other Land. In one scene, Palestinians are protesting the demolition of their homes. They're walking down the road carrying balloons and banners, but the protest is banned under Israeli law, and the army is at the ready alongside them with combat gear, rifles, and stun grenades.

[bakcground play from No Other Land]

David Remnick: No Other Land is opening in just a handful of theaters around the country this week. It's been nominated as Best Documentary at the Academy Awards. Two Palestinian and two Israeli filmmakers collaborated to make No Other Land. I spoke over Zoom with two of them. Basel Adra, who lives in the West Bank, and Yuval Abraham, who lives in Jerusalem. Because so few people have seen this film, I'd like to begin, first of all, this, first and foremost, begins with Basel's life. Tell me where you were born and what was the impulse to make a film about your life and the circumstances of the people all around you.

Basel Adra: I was born in a small community in the southern occupied West Bank, Masafer Yatta, in my little small village called At-Tuwani. I was born and raised there. My parents, like the other families in Masafer Yatta, are farmers, like keep sheep and cultivate the land. This is how the people lives in our area. Today, their life, it's different, for sure, because we don't have access to majority of the land due to the settlements and military bases are built on our land for this past decade. My parents all the time were like activists and were trying to change the reality that we are living in, as you saw a little bit of the stories in the No Other Land documentary.

David Remnick: You wanted to make a film about your community, about the West Bank for a long time?

Basel Adra: For me, it wasn't the idea from the beginning. I started when I was teenager to take a camera and document what's going on around me and to me, to my family, to the community that I live, in order to have the evidence. As well, I was like a bit angry and want the world to know that we face what we face and we're living in these conditions and people should care about what's happening to us and it should not continue.

[background noise]

Basel Adra: This is what's happening happening in my village now. Soldiers are everywhere.

David Remnick: Where were you sending this evidence?

Basel Adra: Some of them used for social media. All of them are in archive on our hand. Some of the footage that we got helped different people in court cases as evidence and as a proof against the claims of the settler soldiers when they try to lie about certain incidents. We would have evidence that we filmed that incident to show to the judge or to the court. This is what we do mainly, to film what's going on and to move in the field with families, with the school students during demolitions. Then Yuval and Rachel came to Masafer Yatta five years ago.

David Remnick: This is Yuval Abraham and Rachel Szor, who were Israeli and started coming to the West Bank.

Basel Adra: Then Yuval and Rachel kept coming to Masafer Yatta almost weekly. The relationship became stronger because we spend more time together and in the field, in the house. Then Hamdan actually had idea and said, when we were like sitting together, like, "Guys, let's make a movie documentary about all the footage that we have." We didn't have the experience in doing so, all of us, but we all agreed in the idea. We started this project five years ago together and we released the movie February 2024.

David Remnick: It seems that as filmmakers, Basel, one of the great assets, advantages that you had, and I don't say this as a joke, is your ability to run really fast with a camera away from dangerous situations. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Basel Adra: Yes. Actually, you're right. I remember now in 2021, it was, to be honest, maybe the biggest settler physical attack against the community that ever I filmed in my life. I got a phone call and there was almost something 60 to 80 masked settlers with guns. They were smashing windows and throwing rocks inside the houses at the people, at cars. People were literally fleeing from their homes to the valleys and to the fields and trying to run away from the settlers. I stood less than 50 meters in front of about 15 to 20 masked settlers. They were smashing a home and two cars near it. One of the settlers saw that I'm filming and he called others and they start to run after me. I was in flip flop, even, not in good shoes to run. For real, it was so scary. I was faster and I made it and I escaped from them.

Yuval Abraham: I hate being with Basel on the field because I'm much slower than him. He always runs. I'm behind him. I smoke more, so I'm less in shape.

David Remnick: Yuval, when you started working on this film alongside Basel and the others, you came to this from what background? You're an Israeli citizen, am I correct? Jewish?

Yuval Abraham: I actually came to this through journalism. To even go even a step backwards, in a way, I came to this through the Arabic language, I think, because when I was younger, I studied Arabic. I grew up in quite a mainstream Israeli town, not meeting Palestinians, not knowing a lot about what is happening in the West Bank. After I began studying Arabic, it really changed my life. It changed me politically, but I think also emotionally. My grandfather, who is a Jewish person, born in Jerusalem, and his family is originally from Yemen, he spoke fluent Palestinian Arabic. Then after this family connection, I began also meeting Palestinians first, Palestinians who are citizens of Israel. Gradually, I began going more and more into the West Bank. I think the knowledge of Arabic and Hebrew is what's made me a journalist.

David Remnick: A lot of the footage that you gathered with your colleagues and a major focus of the film is on home demolitions conducted by Israeli military or Israeli crews. Could you explain what that's about, Yuval?

Yuval Abraham: Wherever you look in the West Bank and also inside Israel, for example, in the Negev, you see Palestinian houses being bulldozed. You see Palestinian villages where they have no connection to water or electricity, and they are unable to obtain a permit. The Israeli military declines. It's almost 99% of Palestinian requests for building permits, according to data that the military has supplied to organizations like Bimkom and others, Israeli human rights organizations that are researching this issue.

When I looked in the Israeli media or I began talking to Israeli friends from where I grew up or my family, the response I always got was, "Well, they're building illegally. This is a legal issue. They did not obtain a permit, and it's illegal." When I began researching and looking at documents and looking at statistics, you very quickly realize that it's a political issue, that there is a systematic effort to prevent this acquisition of building permits.

I think, for me, what was most important and shocking when I first met Basel, this is like the first day that we met, I remember there was a house demolition happening in Basel's village, and we ran to it. I remember the soldiers threw stun grenades and they kicked this person out of his house and destroyed the house. There was so much violence there at that moment. I remember the children looking at it, and the family then not sure what to do, and where will they go and where will they sleep. I felt it's very wrong that this is happening. I felt a certain responsibility, I guess, to communicate that first and first most to Israelis. I began writing mainly in Hebrew. Something about that experience really drew me back to come back to Masafer Yatta and to basically witness this happening over and over again.

[background noise]

Speaker 4: It's 2:00 in the morning and you're demolishing our houses?

Speaker 5: They are refusing to give us permissions or master plans for our village, but they come and demolish our homes and keep saying to the media that we are building illegally.

David Remnick: What can a film do? What can a independent film like yours do? What kind of effect can it have?

Yuval Abraham: I can tell you what I know for sure, that films have effects on individuals and they change the hearts of individuals. The only reason why I know this for a fact is because it happened to me. When I was younger, I remember I watched a documentary called 5 Broken Cameras, which was also nominated for an Oscar and was created by an Israeli Palestinian team. It really, really touched me, and it really made me question some of the beliefs I grew up with.

David Remnick: Because what kind of narratives were you raised on about Palestine and Palestinians as you were growing up?

Yuval Abraham: I grew up 25 minutes away from Basel's village, near the Be'er Sheva area, which is in the south of Israel. I lived my life. You don't know or you don't see, or maybe you see, but you tune out of the realities happening in the West Bank and what Basel's community has been going through. I would always hear about Palestinian teenagers in the West Bank throwing stones at Israeli soldiers or at Israeli settlers. When you don't know anything about the context, when you imagine that they're just living normal lives like your lives, the explanation that you put on these acts of violence is always going to be, they're doing that because they hate us, because they are evil.

David Remnick: Do you extend that understanding to something like October 7th?

Yuval Abraham: No. Look, I do believe that, and I'm not the only Israeli, Israelis talk about this all the time, that part of the conditions, which allowed for October 7th was an Israeli right-wing policy for decades that set to empower Hamas in Gaza. We can more moderate Palestinians keep a separation between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank to prevent a Palestinian state. I do believe that people retain moral agency. I think horrible war crimes were committed on October 7th. Three people that I knew were killed on October 7th. Even people who are oppressed still have moral agency. Kidnapping children or massacring civilians is wrong. The people who are committing that have a moral responsibility.

I see this tendency both in the Palestinian side and also in the Israeli side to not assume responsibility for crimes or actions because the other side has committed crimes. Looking at October 7th, it's almost a year and a half since, where if 38 Israeli children were killed on October 7th, each one of their deaths is a crime. We have now in Gaza 17,000 children, 10,000 children who are missing. When you talk with Israelis about this, they have this mirror image of justification where they point to the crime of October 7th and say, "Well, this justifies everything that we have done since."

David Remnick: Yuval, do you feel like a stranger in your own land politically? Because the polls would suggest, my interviews would suggest, the Israeli press would suggest that the way you look at the situation now is utterly alien to Israeli society.

Yuval Abraham: My views are a minority view in Israel.

David Remnick: I don't mean a minority, I mean a vanishingly small minority, no?

Yuval Abraham: You're right. Recently, there was a vote in the Knesset about a statement where the Israeli Knesset said there will never be a Palestinian state. There are 120 Knesset members, parliament members. The statement passed, and only 8 parliament members, I think it was 8, or maybe it was 9, opposed out of 120. Most of the eight were Palestinian Israelis. There was only one Jewish-Israeli parliament member who opposed that. This is a pressing issue and it's very terrifying for me because I think that you are right. There is no discourse here locally that could lead to a political solution, and we are hungry for hope.

David Remnick: Basel, there's a very powerful scene in the film that shows a peaceful protest against the destruction of your village and other villages. Can you describe how dangerous peaceful protests can be in the West Bank? It's not really legal to protest, is that right?

Basel Adra: No, under the military law, it's illegal. We can't have any protest against the occupation. It's very, very dangerous sometimes not just in Masafer Yatta. All over the years, many Palestinians lost their life protesting against the occupation on those kind of protests. In our documentary, you can see the story of Harun Abu Aram, a guy like our age who was shot in his neck by Israeli soldiers, just because he tried to protest the soldiers taking the generator that his family used for electricity. He was paralyzed for two years and then passed away due to his injury.

David Remnick: Basel, you have been showing this film all around the world. What has been the result of your touring this film?

Basel Adra: Yes, around the world were very emotional. A lot of them would cry and also stand up and greet us. It's amazing, I think. We didn't thought, to be honest, when we were working in this movie that we will get this amount of awards and be nominated for the Oscar, which is all important for the movie and the story itself. On the other side, it's sad because we made this movie from a perspective of activism to try to save the community, to try to have political pressure and impact for the community itself. Unfortunately, all the reality today is changing at the opposite side, which is to be more miserable and bad.

David Remnick: The reality on the ground?

Basel Adra: Yes.

David Remnick: One of the difficult things for a film like this, and look, I feel it sometimes, too, is that you're sometimes preaching to the converted, Yuval. You're showing your film to people who already are inclined to agree with you or in your political camp, and that to reach people whose mind you want to change most profoundly, they're not turning it on, they're not entering the theater, they're not clicking on your film, they're watching something else.

Yuval Abraham: I think this is why the Oscars help, because when a film is nominated, then suddenly-- I see this now in Israeli society. We released the film now online in Israel and Palestine. Of course, it's challenging. I'm beginning to read comments from Israelis who are not necessarily like me. As you said, they're not part of the-- did you call it a dying minority or a small minority, which I hope changes. Because, for me, I feel this is my main responsibility as an Israeli, is to work with the Israeli society and to try to-- I'm going to have a bunch of interviews on mainstream Israeli media and to try to show people the way in which I see the world and to try to convince them to come closer.

David Remnick: I sometimes think that Israeli contact with the West Bank, much less Gaza, is almost solely through the military. I was once writing a piece about Haaretz. I was talking with the owner of Haaretz, Amos Schocken. I asked him about what his experience of the West Bank had been. He said, "I've never been there. I read about it in Haaretz."

Yuval Abraham: Wow.

David Remnick: That is the owner of the most left-wing paper in Israel.

Yuval Abraham: This is a key issue, David. If I look at the few years that we had leading to October 7th, that had the protests against the judicial overhaul, against the weakening of the Israeli judicial system and the Supreme Court, which were policies that Netanyahu had tried to promote, this was something that was led by, let's say, the Israeli center left, the liberal community in Israel, many of them live in Tel Aviv. I would attend those protests because I thought they were important. One word that was missing there, because people were chanting democracy and democracy, that was missing from the mainstream side of this protest was occupation, was Palestinians, was a political solution.

I think that for far too long, the Israeli liberal side has allowed, not only allowed, but had contributed for things that were happening in the occupied West Bank and in Gaza. There's a contradiction here that we are seeing today. I mean, things are related. Many people on the left have warned for many, many years that what is happening to the Palestinians will eventually seep through into the Israeli society. Of course, the Israeli right is getting stronger and then the oppression of Palestinians is getting bigger, and then Hamas is getting stronger, and then by attacking Israeli civilians, the Israeli right is getting--

There is this loop that we are seeing where it's like a win-win for those who do not want a political solution. I think it's really important to understand it's not some binary thing. It's not like either the Palestinians win or the Israelis win. In a sense, it's either we all win or we all lose. I hope that the Israeli liberals, to get back to my previous point, will not continue to protect the occupation or apartheid. We will try to work to have an alternative because we really need this. We need this like water, really. There will be no other way forward if there is no political horizon.

David Remnick: Basel, for many, it's very hard to imagine how things can get any worse in Palestine and Gaza, West Bank, and in the political atmosphere of Israel as well. What do you hope that this film inspires in the people that take the time to see it?

Basel Adra: Well, we did this movie, again, from perspective of activism. For real, we want to change people's minds because many of the people that are going to watch this are somehow responsible because this is their money, this is their government, this is their countries that's supporting this reality and supporting the ongoing occupation, even if in their words, will not say it, but in their actions, this is what they do. We want these people to understand and to inspire them and to encourage them that they should take part in this, in any kind of action, small, big protest, pressure.

David Remnick: How do you imagine the Academy Awards ceremony? If you had that opportunity, very short opportunity, before the music starts and they chase you off the stage, what would you like to say to the world in that brief time?

Yuval Abraham: We have 45 seconds. Basel needs to speak first, I think. If I were to say something concrete about the current moment, I think for me, what is the most urgent thing is that all stages of the ceasefire will be implemented and there's a very high risk. I think in the short term, the pressure should really be on moving and doing all the stages of the ceasefire agreement so we can get out of this current bloodbath that we are in and begin, hopefully, working for political solutions.

[music]

David Remnick: Basel Adra, Yuval Ibrahim, thank you so much.

Yuval Abraham: Thank you very much.

Basel Adra: Thank you.

David Remnick: No Other Land opened in New York and it's coming to a few major cities this weekend. Also on the filmmaking team for No Other Land are Hamdan Ballal and Rachel Szor. The film has been nominated for Best Documentary at the Academy Awards, which are next month.

[music]

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.