David Remnick: It's not every year that begins with front-page headlines about copyright law.

[music]

But 2024 is not just any year. At long last, Mickey Mouse has entered the public domain. Now this is actual news because Disney has been waging a legal campaign for decades to keep its characters under copyright. In fact, one copyright extension law is commonly known, and I'm not making this up, as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act, but time catches up with all of us. Even Mickey Mouse and even the Disney company.

With Mickey now in the public domain, one filmmaker is already putting him in a horror movie. When Mickey Mouse was still new and the biggest pop culture craze ever seen, The New Yorker profiled the mouse, and the man who created him. It's a piece by Gilbert Seldes from 1931, and here's an excerpt.

[whistling]

Chris Kipiniak: In the current American mythology, Mickey Mouse is the imp, the benevolent dwarf of older fables. Like them, he is far more popular than the important gods, heroes, and ogres. Over 100 prints of each of his adventures are made, and of the 15,000 movie houses wired for sound in America, 12,000 show his pictures.

Mickey Mouse: [unintelligible 00:01:22]

Chris Kipiniak: So far he has been deathless. As the demand for the early Mickey Mouses continues, although they are nearly four years old. It is estimated that over a million separate audiences see him every year.

Mickey Mouse: [unintelligible 00:01:35]

[dogs bark]

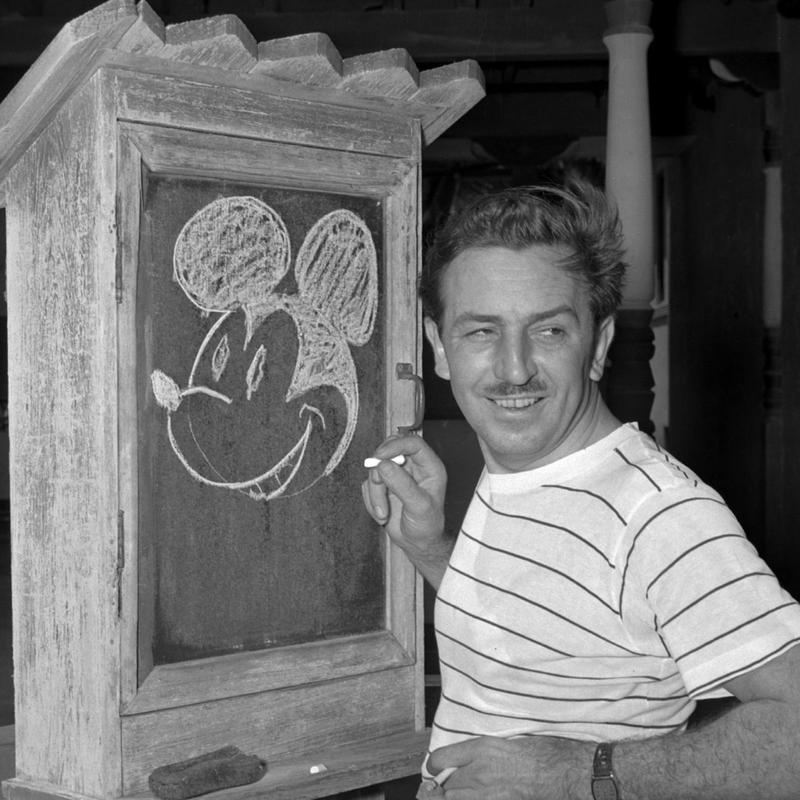

Chris Kipiniak: 13 Mickey Mouses are made each year. The same workmen produce also 13 pictures in another series, the Silly Symphonies so that exactly 14 days is the working time for each of these masterpieces, which Sergei Eisenstein, the great Russian director, called with professional extravagance, "America's most original contribution to culture." The creative power behind them is a single individual, Walt Disney, who happens to be such a mediocre draftsman in comparison with the artists he employs that he never actually draws Mickey Mouse. He has, however, a deep personal relation to the creature. The speaking voice of Mickey Mouse is the voice of Walt Disney.

Mickey Mouse: Hello, Minnie. There is a great big [unintelligible 00:02:27] you better watch out. He's hoping to get you, Minnie.

Chris Kipiniak: Mickey Mouse pictures are talked into being before they are drawn. Talked and cackled and groaned and boomed and squeaked and roared and barked and meowed, with every variation of animal sound with appropriate gesture and with music. If strange outcries and queer noises waken Mrs. Disney at night, it is only Walt working on a new story.

[dogs howling]

Chris Kipiniak: When a mouse or a silly symphony is finished, the business side and most of the artists watch it carefully for commercial value. For those mysterious qualities which they think or guess will make it popular. They find their congratulations to Walt Disney accepted without enthusiasm. He is not putting on artistic side. He is not indifferent to profits. What he is frequently doing is referring each finished picture back to the clear idea with which it started. The thing he saw and heard in his mind before it ever came to India ink and soundtracks.

In the process of making the pictures, something often escapes, and Disney wanders moodily away from the projection room grumbling, "Where did it go to?" Often, will begin outlining the original idea again with gestures and sound effects to prove that he is right. He is a slender, sharp-faced, quietly happy, frequently smiling young man, 30 this month. He is a simple person in the sense that everything about him harmonizes with everything else. His work reflects the way he lives, and vice versa.

Mickey Mouse is far removed from the usual Hollywood product with its sex appeal, current interests, personalities, studio intrigue, and the like. Disney, living in Hollywood, shares hardly at all in Hollywood's life. He goes to pictures, but rarely to the flash openings. He neither gives nor attends great parties. Outside of the people who work with him, he has few friends in the industry.

The only large sum of money he ever spent was $125,000. It was the cost of his new studio. Everything he earns and everything his brother earns on the 50/50 basis they established years ago, is reinvested in the business.

[music]

Leaving the distribution of the films to others, the Walt Disney Corporation concentrates commercially on the creation of movie audiences. Disney's own connection with the vast enterprise, which now enrolls three-quarters of a million children in Mickey Mouse clubs, is not close. The clubs are an invention of an enterprising member of the business staff, and Disney's only interest in them is as a source of knowledge. He learns from them what children like.

The club members attend morning or early afternoon performances at movie houses led by a Chief Mickey Mouse and a Chief Minnie Mouse. They have a club yell, an official greeting, a theme song, and a creed. As I find myself a little unsympathetic to this activity, I shall limit myself to an exact quotation of the creed.

Children: I will be a square-shooter in my home, in school, on the playground, wherever I may be. I will be truthful and honorable and strive always to make myself a better and more useful little citizen. I will respect my elders and help the aged, the helpless, and children smaller than myself. In short, I will be a good American.

Chris Kipiniak: I have kept Mickey Mouse in the foreground because in general, it is with Mickey that Disney is identified, but I belong to the heretical sect, which considers the Silly Symphonies by far the greater of Disney's products. Although there is a theme in each one, Disney's imagination is freer to roam. The symphonies have no central character and no clearly defined plot. In them, the animals and vegetation purely incidental to Mickey Mouse are brought into the foreground.

Mickey Mouse: [sings] La, la, la, la. La, la, la, la, la. La, la, la, la.

Chris Kipiniak: The symphonies reinforce what the Mouse tells us about Disney's character. His delight in quick surprises, his uncomplicated sense of fun, his keen observation, Mickey Mouse has correctly four fingers, not five. In addition, they suggest his passion for all animals. Disney once dropped his work and ran all over the vacant lot near his studio when he heard that a Gopher snake had been seen there.

He watched some sparrows for hours while they beat off a hawk and set up their nest, and he likes enormously the kind of laughter he himself creates. Laughter at absurdities and impossibilities. Out of these natural simple interests, backed by enormous files of pictures, cross sections, and data on every animal extent, he creates the Silly Symphonies.

In one of these occurs a moment typical of Disney's method. A frog dances on a log, its shadow following in the pool below. Presently, the frog moves to the opposite end of the picture, the shadow stays where it is, but continues to reflect the dance. Then it joins the owner. Perhaps 15 seconds cover the incident. It is a grace note of wit over the broad humorous symphony of the whole picture.

With a picture to make every two weeks, both Disney and his associates have to use certain formulas like the dancing of animals and chairs, chases, and the sudden elongations of necks and legs. The freshness of picture after picture proves that the creative force behind the formula is still powerful, and the combination of ingenuity and innocence, which was typical of pre-war America, can still give pleasure.

At the end of three and a half years, Disney's ingenuity seems more fertile than ever, and his innocence is attested by the fact that he can think of nothing better to do with his time, his talent, and the 5,000 a week or thereabout which he earns, than to put all of them back into the work he enjoys.

David Remnick: That's from Gilbert Seldes's profile, Mickey Mouse Maker, published in 1931. Chris Kipiniak read the excerpt for us, and Mickey Mouse, at least his early incarnation, entered the public domain just this month.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.