Julianne Moore Explains What She Needs in a Film Director

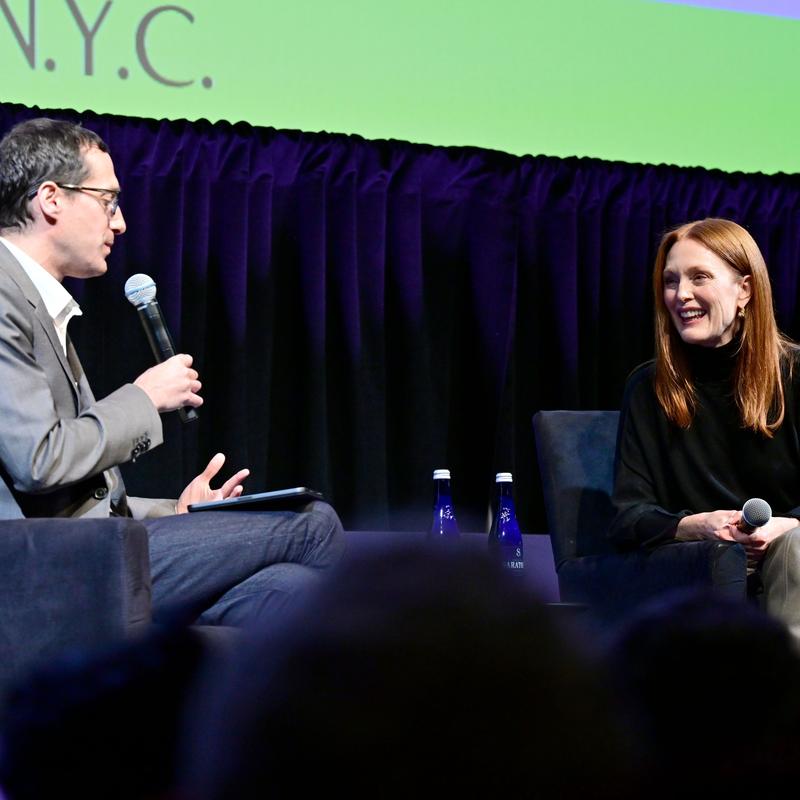

Speaker 1: At the New Yorker Festival recently, we were joined by a film actor we can legitimately call a legend.

Michael Schulman: Whether she's playing a 1950s housewife, a 1970s adult film star, a linguistics professor losing her memory, or Sarah Palin, she brings depth and humor and tragedy, and incandescence to all her roles. She's the author of the bestselling children's book Freckleface Strawberry.

Speaker 1: Staff writer Michael Schulman sat down last month with Julianne Moore.

Michael Schulman: The following is only a partial list of the directors she's worked with. Robert Altman, Louis Malle, Todd Haynes, Paul Thomas Anderson, Lisa Cholodenko, Steven Spielberg, the Coen Brothers, Ridley Scott, Stephen Daldry, Alfonso Cuarón, Rebecca Miller, Jesse Eisenberg, Tom Ford, Kimberly Pierce, David Cronenberg, Julie Taymor, and George Clooney, and she's just added to the list Pedro Almodóvar in his first English language feature, the Room Next Door, co-starring Tilda Swinton.

Speaker 3: Have you decided where we're going?

Speaker 4: That's why I called. It's near Woodstock. It's about two hours from the city. It looks fantastic. It's a bit expensive, but, hey, the occasion calls for it.

Michael Schulman: Please welcome the gigantically gifted Julianne Moore.

[applause]

Julianne Moore: God, I'm so flattered. Thank you very much. Thank you.

Michael Schulman: Let's start with that list because, my God, that's just an incredible roster of people. I'm curious, when you choose roles, how important is the idea of wanting to work with someone or wanting to work with someone again versus a particular character or the script? Do you have a life list, a birder, or something of directors?

Julianne Moore: First of all, we don't have as much choice as you think. That's what's interesting. As you were going through that list, I thought, "Wow, I never ever thought in my life I would work with that roster of talent." My film career didn't even start until I was 30. Before then, I was really working in television. I started on a soap opera, and I did lots of-- Yes, right on. Let's hear it for As the World Turns. I just got the jobs I got.

I came to New York thinking that I was going to work in the theater. Then I also thought that somehow I could work at a regional theater for the rest of my life, which is difficult to do, and ended up mostly doing television stuff and auditioning for Broadway things and not getting it and feeling frustrated by not getting any film work. Then when the independent film world started in the early '90s, suddenly my life changed. One of the people who changed it was Robert Altman.

Michael Schulman: Right. Shortcuts.

Julianne Moore: Right. He saw me in a production of Uncle Vanya that became Vanya on 42nd Street, which Louis Malle filmed. At that same time I also auditioned for Todd Haynes' For Safe. Those three movies came out at the same time in the early '90s and completely changed my life. It wasn't intentional. I didn't seek these. It was just this weird confluence of opportunity and I suddenly had this film career.

Michael Schulman: Yes. However, when I look at this list of directors and I've been throwing myself at Julianne Moore Film Festival over the last couple of weeks, which I've really enjoyed, what's striking is how these are all very visionary, auteur directors that you've worked with. They're all very different and yet you're able to really fit yourself into all of them. I can only imagine that an Altman film is completely different than being in at least a Cholodenko film or a Cronenberg film.

How do you figure out what that means for each director? Are you going back and watching their previous movies? Are you just sitting down and discussing with them what is the style that you want or is it more intuitive?

Julianne Moore: That's an interesting question. I think that the most important thing about a director is point of view. When people ask me, they'll say, "Why is Ridley Scott so special?" or "Why is so and so different from this other director" I'm like, "I don't really see the differences. What I see is that through-line of point of view. All of them have a really distinct way of telling a story." A lot of them write their own scripts as well. That's something I've been very drawn to, people who are also writers.

I can find tell in the language, especially with first-time directors, what they're trying to communicate. That's really important to me, the language, and then you see it in the frame. Todd and I, when we did Safe, we didn't have a lot of time. We didn't have any time to really talk. We had a little bit of rehearsal. I felt like the language was very specific, but then I would always ask him to show me the frame. He had a lot of storyboards too.

Then I could see from the way he was looking at it in combination with the language where I was supposed to be in it, how he saw me. I was always searching for, once again, his point of view. Where does my character exist in this narrative?

Michael Schulman: See, but this is totally fascinating to me because a lot of the actors who I have spoken to absolutely will not watch themselves on playback. Someone like Adam Driver, for instance, I profiled him. He won't ever watch anything he's in. If you try to make him, he'll run to the bathroom and throw up. How does that not make you get inside your own head? Self-conscious? What are you getting out of watching yourself as you are shooting?

Julianne Moore: Interesting enough, I don't like to watch the final product. Back in the day when we had dailies, I hated dailies because dailies are-- That's the footage that you shot that day, so you've already shot it. It used to be that people would watch their own dailies. Then I don't know. It made me feel sick because I can't change it at that point. I've done it. I love playback because playback, I'm like, "Oh, there's the frame, there's the camera movement. That's where I am. Oh, that lens is-- I'm bigger than I thought. Oh, I'm further away. I need to do--"

Playback helps me adjust. Storyboards are fantastic. I like to look through the lens. All of those things inform what I'm doing. Once it's done, forget it. I don't want to see that. That's a mess, but in the process of making it, it's very exciting to watch it.

Michael Schulman: That's partly why you're such a director's actor because that's a kind of directing of yourself. Analyzing how you look in a frame and figuring out what to change.

Julianne Moore: Yes. I feel like it's a tool. I'm always like, "What do they see? What are they communicating?" Everything in film is a communication. That's why I always hate that, "Let's see what happens," kind of directing, because I'm like, "No," or the script is a blueprint. I'm like, "No, the script is not a blueprint. It's Specific." Shots are specific. All of those things add to our understanding of a story.

Michael Schulman: Without naming names, are there other things that directors have done that have turned you off or made you alienated you from their process, where you're like, "I can't really work like that?"

Julianne Moore: When they don't have a shot list, that's really, really hard, because then I'm like, "Well, wait." If you get to the set and the director hasn't prepared and they don't know how they want to shoot something, I feel lost because I'm like, "Well, wait." Then I don't understand how you see it. How am I supposed to do my work, too? It feels too general to me, actually.

Michael Schulman: What was Altman's process like? He seems like it was very freewheeling in a way. Maybe I'm thinking of Nashville, which is a sprawling [crosstalk].

Julianne Moore: Exactly. I don't think I mean you have to be strict with your shots so that they have to be tight or something, but Altman first of all, he was a person that made me want to be a film actor, because I made it all the way to college without ever having seen an Altman film. I missed everything in the '70s, and it wasn't until the '80s when I got to college and I saw three women in a revival house that it woke me up. I'd never seen that kind of acting before, and I'd never seen that point of view before.

I'd never seen this naturalism to it. I was like, "That's what I want to do. I want to work with him. I want to do that kind of work." He had such a generous viewpoint of humanity. He so loved individuality and flaws and just everything that was weird about us. He put all these people in a room, and everyone thought it was chaos, but it was very-- Even with the improv, you might say something, and then the next one he'd go, "Okay, now you say that, and you say what you said before."

It was like there was this incredible shape to it with the way he was shooting it and with language. We were all in this pen that he controlled, but you knew where the boundaries were. He always created a boundary.

Michael Schulman: What about Almodóvar? What struck you about just-- Obviously talked about somewhat, the point of view, is a very strong one. What stood out to you about just his process of directing?

Julianne Moore: What I didn't understand about Pedro was that everything in his movies is so intensely personal that I think I thought, because I'm an American, too, when I first saw Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, I was like, "Oh, Spain must be like that." I know. Then I learned. I was like, "No, that's not Spain," but when we were there and Tilda and I walked into his apartment, I saw every single one of his movies in his apartment.

All of the stuff. The red kitchen and all the little figures and the stacks of books and DVDs and their opera was on. The lights were low. I was so overstimulated, I was like, "I don't think I can concentrate," but that's his world. Then after working with him and meeting his producers and other people on the crew, I realized I'd seen them all in his movies, too. Even the people are in there. Everything that he does is drawn from his life.

He would bring jewelry to the set that he said, "If anybody wants to wear this pin, you can put that on today," and be like, "Okay." All of it, that's his language. That's his imagination. You're in it. I think he also has seen everything in his head. You're always thinking, "Okay, how do I fulfill this vision that he has of this film?"

Michael Schulman: My colleague John Lahr wrote a profile of you in the New Yorker in 2015, and there's a quote in it from Wallace Shawn, who is in that Uncle Vanya production with you. He said, "She comes from a military background. She takes a military approach to her very unusual job. Her orders are to turn into a complete maniac on Tuesday at three o'clock in the afternoon, and so she guiltlessly does that." Is that right? Is that how the military brat life rubbed off on you in a way?

Julianne Moore: No. My father was the person who was in the army, and he was a paratrooper and a helicopter pilot. A really smart, wonderful person who's very liberal and not rigorous about behavior or anything like that. I think I love to learn. I like to read. I like to ask people about what's going on. I like all of those things, but yes, I love structure because I think that I can do all that kind of stuff, and then when the camera's rolling, I'm free, and it's safe.

One of the things that always rubs me the wrong way is when somebody calls an actor brave. We're not brave. We're having a great time. We are pretending and that's wonderful. You've created all these circumstances to be free and have that moment to think, "What would that feel like? How can I make myself fee that? How can I engage in that?" The minute you say cut, you're like, "Oh, I did that." It's a little bit like back with Bob Altman. He made you feel safe. He gave you a container so that you can explore this.

I think the instinct to act or for any creative endeavor, I think there's pleasure involved. Why are we attracted to it? We don't have to do this, but you start doing it and you're like, "I like this. It feels good." There's plenty pleasure in it.

Michael Schulman: As you mentioned earlier, your first big break was on As the World Turns. My impression of being on a soap is that it's like you get in there, you have to cover 30 pages in a day, and it's just like, "Go, go, go, go, go." Is that what the process is like?

Julianne Moore: It's really, really fast, and you learn to be prepared. Know your lines, know what you want to accomplish, and then try to-- I actually would watch myself on television to see how bad I was, and it helped.

Michael Schulman: That was like an early version of watching yourself in the playback?

Julianne Moore: Yes, it was, because I was stiff. I had a terrible voice. I had a voice like this on television.

Michael Schulman: Todd Haynes, who you've made, I believe, five movies with at this point. Of course, there's Safe, Far From Heaven, most recently, May December. We have a clip from Safe. Basically, you're playing Carol White, who is a woman living in LA in the '80s, and she's redecorating her living room and stuff. Suddenly she starts experiencing these bouts of mysterious affliction, like a coughing fit or a runny nose, and she's not sure what's happening with her. This is a scene with her and her psychiatrist. Let's take a look.

Psychiatrist: Do you work?

Carol White: No, I'm a house-- I'm a homemaker. I'm working on some designs for our house though in my spare time.

Psychiatrist: You have one child?

Carol White: My husband's little boy. He's not my son, he's my stepson, Rory. He's 10.

Psychiatrist: How long have you been feeling unwell?

Carol White: About two months, three. I've been under a lot of stress lately. Then my friend Linda and I, she's probably my best friend. She lives down the-- Anyway, we started this fruit diet together. I think that set it off.

Julianne Moore: Poor old Carol.

Michael Schulman: I know. It's a great movie. Do you remember anything about that particular scene? About being inside of that scene and how you approached it?

Julianne Moore: I think that was Todd's mom's suit that I was wearing.

Michael Schulman: Oh my gosh.

Julianne Moore: We shot a lot. We shot in his grandparents' driveway. We shot at his uncle's house at the beach. It was a million dollars making the movie.

Michael Schulman: Wow. You can tell obviously the breathy voice. Why was that the thing you-- Was it instinct or did you have an intellectualized reason for that?

Julianne Moore: It was instinct, I think when I first read it, but I also thought this is a person who's not comfortable in her body. She can barely make contact with her own throat, her own vocal cords. She doesn't want to make any sound. She talks about her son. It's not her son, it's her stepson. She doesn't like to take up a lot of space. She wants to be attractive and offensive and doesn't want to offer herself. He's like, "We want to hear from you," and she's like, "What?"

She's been completely defined by the world that she lives in, by consumerism, capitalism, by her marriage. She not working, she's absorbed. She spends her time on a fruit diet and at aerobics and buying her couch. Then suddenly, she feels terribly ill. The fabric on the couch makes her feel sick. She has a seizure at the dry cleaner and she's confused. Everything that tells her who she is makes her sick and she doesn't know why.

Michael Schulman: That choice about where her voice lies reminds me a little bit of In May December, your most recent Todd Haynes film, where you had a lisp. Did it come and go a little bit? I noticed it at certain moments more than others.

Julianne Moore: We were very specific about it because people only lisp on certain sounds. There are sounds where the lisp will be more pronounced, but Todd and I talked about that, and what I wanted with the lisp is that a lisp is often a characteristic of childhood because it can be like a tongue that's not quite developed yet. Now, obviously, when people have actual speech issues, there could be a lot happening that's not addressed, but with this particular character, I wanted it to be a signifier of how she thought of herself.

This is a person who thinks of herself as a child and thinks of herself as a princess. She's not the queen. She's still a little girl. She's still the princess. He's the prince who rescued her. In order for him to rescue her, she has to be the princess. This was another manifestation of the way she felt in the world and what she was projecting in the world. Todd and I talked about it, and we talked about the specificity of the lisp, too. It made sure it was always really, really specific.

Michael Schulman: It's interesting to see that clip where she stumbles over the word housewife because you've played a lot of great housewives. Of course, I remember the year when you were nominated for two Oscars for playing two different unhappy 1950s housewives in The Hours and Far From Heaven. Is that a fluke, playing people who are stuck in the domestic realm, or is it something that you sought out that you were interested in for a particular reason?

Julianne Moore: I think that was a fluke. That year in particular was frustrating to me because those parts were so different.

Michael Schulman: Oh, absolutely.

Julianne Moore: I don't know that I seek out things in the domestic space, but I do think I'm really drawn to ordinary lives. I like people. I've never been like, "I'm going to play an astronaut next." I don't think that way. I always think, "What is this emotional dilemma? Why is this compelling to us?" I always think of that thing in the New York Times, My Sunday Morning, and we all read it avidly like, "Oh, she gets up at 8:30, and then she has one cup of coffee and then a banana, and then she goes for a run."

I read it all the time, and I'm like, "Why do I care about the banana?" I care because she's a human being like me. I'm really interested in how she approaches her life and what she does and what she thinks. All of these things hopefully give me a deeper understanding of what it is to be a human being. A lot of these domestic stories, that's the biggest story of our lives. How do we live? Who do we love? Where do we live in our communities? Those are the things that we all know about. We know about that.

I don't know what it's like to be a queen. I've never met a queen. Maybe I'll try to meet a queen. I don't know, but I do know about this. We all know about this. It's fascinating.

Michael Schulman: You are yourself an ordinary person.

Julianne Moore: Yes.

Michael Schulman: One other interest of yours, which is the Knicks. You're at Knicks games all the time. How did you get into basketball? What do you see when you're watching the Knicks?

Julianne Moore: Frankly, it's not me. It's my family. It's my husband and my son who are here with his fiance. Not my husband's fiance, my son's fiance. They're big basketball fans. It's a family thing. I didn't know. I grew up with a dad who watched football and I never really watched basketball. What I love about watching basketball is that you can see their faces and there is so much drama. You see their faces and you see their bodies.

All these other sports, I feel like in baseball and in football, I don't know what's going on but they're so exposed and I really like that. I love the drama of it. Sometimes it's heartbreaking, really.

Michael Schulman: Julianne Moore, thank you so much for doing this. It's such a privilege to be able to talk to you.

Julianne Moore: Oh, thank you. Thank you so much.

[Applause]

Speaker 1: Julianne Moore, at the New Yorker Festival last month. She's co-starring in the room next door alongside Tilda Swinton, and it just opened.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.