Ian Frazier’s Tour of “Paradise Bronx”

David Remnick: This is the New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. Ian Frazier has been writing for the New Yorker since the '70s, when he was fresh out of college. Ian, or Sandy, as most of us call him, is a writer of tremendous range. He's written some of the funniest pieces we ever published, but also a tremendous body of deep and sensitive nonfiction reporting. He's got a unique gift for capturing the essence of a place. He's written about the Great Plains, about Siberia, about Staten Island, and we just published a piece by Ian Fraser about New York City's sometimes most overlooked borough, the Bronx.

Ian Frazier: The Bronx is a hand reaching down to pull the other boroughs of New York City out of the harbor and the sea. Its fellow boroughs are islands or parts of islands. The Bronx hangs on to Manhattan and Queens and Brooklyn, with Staten Island trailing at the end of the long tow rope of the Verrazano Narrows bridge and keeps the whole business from drifting away on a strong outgoing tide. [music]

David Remnick: That passage is the opening of Ian Frazier's new book, Paradise Bronx. It came out of 15 years worth of long walks through the city streets of that borough, and on a recent very hot morning, Fraser invited a colleague to join him, the editor and writer Zach Helfand.

Zach Helfand: He told me to meet him at the 170th Street station underneath the elevated tracks on Monday at 9:30, and he said to bring comfortable shoes, sunblock and water. Hi, Sandy.

Ian Frazier: Hi, Zach. How you doing?

Zach Helfand: Like many people in the New York metro area, I know of the Bronx mainly from driving through the Bronx across Bronx Expressway or the Major Deegan or the Bruckner. That's not how Sandy sees it. Sandy sees it at street level, on a human level, and that's the Bronx that he wants to show me. The first stop is we're going to walk west to the High Bridge, the pedestrian bridge that spans the Harlem River. All right, should we head off?

Ian Frazier: Sure enough.

Zach Helfand: What percentage of the streets or blocks would you say you've walked at this point?

Ian Frazier: I have no idea. I mean, I have tried to cover it pretty thoroughly, and I set out to walk a thousand miles. I don't think I did, but I walked a long way up here. I've walked a lot up here.

Zach Helfand: There's so many senses in the book. There's so many sounds, and you started walking in the Bronx because of your nose, right? You were following your nose?

Ian Frazier: Yes, yes. The first big piece I did about the Bronx was about the Stelladoro Bakery, and that was on 236th and Broadway. The Major Deagan runs right behind the Stelladoro bakery. When I told people-- I had this happen a few times- where I would say, "I'm doing a piece on the Stelladoro bakery. People who had driven on that would go, "Oh, yes, we could smell it when we went behind it," going up to wherever they were going.

One woman told me when they went someplace, she lived in the Bronx and when they smelled the Stelladoro cookies, she knew she was almost home when she was a little girl. The smell of cookies in a neighborhood is an amazing resource. It makes it a nicer place. I wanted to find how far that smell extended from the bakery, and so I would just walk along and walk a few blocks, and, Yes, I can still smell it. A few more blocks, yes, I can still smell it. Sometimes it would be like a mile and a half, two miles. If the wind is right, you're still smelling those cookies way far from the bakery.

That bakery was crushed by a private equity company that bought it and then lost money on it and sold it to a company who moved it to Ashland, Ohio.

Zach Helfand: Why from that, write a book that's basically a love letter, in some ways, to the Bronx?

Ian Frazier: Well, my first book of this kind was Great Plains, which is about the middle of the country. People would say to me, "Oh, yes, I flew over it. There's nothing down there." People flying from New York to LA, they say, "There's nothing down there," or people were calling it the flyover country and that got my backup. This is one of the coolest places in the world. Dodge City is out here, for heavens' sake. There's all kinds of cool things out here. I like to look at places that people aren't seeing, and the Bronx is not only people don't know about it, but what they know is wrong, or is just really a gross oversimplification. There are places in Europe where a Bronx means a slum. I just wanted to know this should not stand, because this is a really cool place.

Zach Helfand: Shall we make our way over to the hybrid?

Ian Frazier: Absolutely.

[music]

Zach Helfand: Oh, so this is it right here. It's just you're at the bridge.

Ian Frazier: You're at the bridge, and you got to go this way because bicycles go down that way. I have come close to being run over a number of times.

Zach Helfand: I've seen the High Bridge a million times, usually driving on the Harlem River Drive in Manhattan and it's really striking. It's got these stone arches really high. It looks like a roman aqueduct, and it turns out it actually was an aqueduct back when it was first built. Now, from this approach where we're walking, it looks entirely different. We're going up this long ridge, and then all of a sudden, you can see the hills of Manhattan in the distance and this big sky. There's this long promenade leading from all those things that invites you to walk on it.

Ian Frazier: First, we're going to look this way. When I come out here, I think about Edgar Allan Poe. Poe moved to the Bronx in 1844 with his wife, who was also his cousin, Virginia Clemm. They moved there because she had consumption, which is now called TB. They thought that the good Bronx air would be good for her lungs. Well, that was then. They lived on Kingsbridge Road in a house where you can still visit, and she died there. Poe was just grief-stricken. This is another walker in the city. He walked all over the Bronx in his grief and misery. He would come out here and just stare down at this wild scenery, which then was wild scenery.

Zach Helfand: Right now, it's busy and not very pretty to look at, but you can imagine when he was here. It's a nice place to be sad and forlorn and melancholy.

Ian Frazier: Right.

[train honking]

Ian Frazier: I just love that. It was not only a wild place, this was an architectural wonder that this was built. The High Bridge was running. The aqueduct was working and running water across it by 1842. It was a really important improvement in New York City's infrastructure because New York City then was just the tip of Manhattan Island. It had really poor water. It had water that people would catch cholera from. It also didn't have enough water to fight fires. It had a cholera epidemic in 1832, a very bad fire in 1835, and they built the aqueduct system up to the Croton River in order to take water down to the city.

The reason this bridge is high is that the whole thing is a. It's a gravity feed, so it just flows downhill to the city. The water, when it gets there, has enough pressure to go up four or five stories, and so now we can look north.

[music]

Zach Helfand: Looking down, we're right on top of a roadway, very busy roadway. There's train tracks on the other side and fencing, and then farther off in the distance is just this tangle of infrastructure, loops and helixes and cloverleafs kind of all jumbled on top of each other.

Ian Frazier: You're looking at all of this infrastructure just like, wow, all just together. When they were building the connections, all these things, when they were unfinished, the engineers referred to them as chicken guts. It was so confusing and weird to look at. When you see a picture of this, like an aerial photo, it's astonishing all the ways that they managed to hook all these things up together. Up here, I'll show you where we can walk.

Zach Helfand: We've talked about the wonder of the infrastructure and just how much of a technological marvel it is, but it also came at a great cost. Right?

Ian Frazier: Well, it is funny because when I look at the High Bridge and think about the High Bridge, it's just like the highest achievements of man. It's like, "Isn't this great?" but the Cross Bronx, the bridges that lead to the Cross Bronx and the Cross Bronx were also engineering achievements, but at an enormous cost to the people who live in the Bronx. What it did was it brought this rush of traffic and just changed how you thought about the place. It made it a place that you drive across. It made it a place that you drive through. Any place that people pass through going to and from suffers.

If you're on a highway and you're going somewhere, I believe that things in motion have disdain for things that are not in motion. I think that when you look out your car window, you're like, "So long, sucker." You know that that's a natural attitude for people to have, and it inflicts harm on places.

Zach Helfand: There's the obvious harm. There's the noise and the traffic and the entire neighborhoods that were uprooted to make way for these roadways. Then there's the less visible harms. There's the air quality. The asthma rates in the Bronx are higher than anywhere else in New York City.

Ian Frazier: We're going to go down these stairs, and we'll walk along Cedric Avenue, and we will be in the historic sites in the 1970s era of the Bronx.

Zach Helfand: The route we're taking along Sedgwick Avenue begins as a service road that takes us right through those chicken guts that the engineers were talking about.

Ian Frazier: Now we're seeing what this is like at kind of river valley level, and see, I just love these. It's like this is the foundation of the Earth.

Zach Helfand: These are the pylons underneath the bridges.

Ian Frazier: These are the pylons that hold up the Hamilton bridge.

Zach Helfand: There's no sidewalk down there, and the side of the road is overgrown with all this plant life. Sandy is walking ahead and parting these weeds so we can walk through. [music]

Zach Helfand: Okay, so we're bushwhacking right now. We're on the side of a fairly busy road on a dirt path, and we're sometimes raising our arms above our waist to get through the overgrown weeds. You call the book Paradise Bronx. What and when was the paradise?

Ian Frazier: Well, I mean, as I broad brush view of Bronx history, the Paradise Bronx was when you had all these paved streets after the Bronx was built up in the 1910 and 1920s. Not very many cars and kids would just play in the street. If you look at the pictures, some of the paving was just smooth. It looked beautiful, and so you could draw on it. You could draw hopscotch squares on it. You could play marbles on it, so that period, which is like 1920 to, I don't know, I say until the completion of the Cross Bronx Expressway, which was 1963, that was a time when that people who lived here just remember it with such fondness. Where everybody was just on their stoops and hanging out.

Zach Helfand: Then what happened?

Ian Frazier: Well, the buildings got old, which was a real problem. The buildings had gone up in a rush in the building of the Bronx that followed the subways. The subways came here from 1905 to, like, 1930, but all the Bronx was just built up in a real estate frenzy. Tthose buildings aged, fell apart, and they started burning, and that's kind of what happened.

Zach Helfand: The story that I had always heard growing up was that people were just burning the buildings, but you said there was some arson. In most cases, that wasn't the case. Right?

Ian Frazier: Reports by New York City fire marshals said that only a small proportion of the fires were started by arson. They burned because they weren't well maintained. They burned because they needed new wiring. They burned because too many people were in a building, and there wasn't enough heat and somebody was using a space heater. There were just all kinds of reasons, but it did become a plague. It just happened it was just one building after the next.

Zach Helfand: What did the government or the greater civic world do to help or not help the situation?

Ian Frazier: Well, at first, they did not help. The idea was that this was going to just kind of disappear. There was an idea called 'planned shrinkage.' The plan had moved industry out. The basic idea of the metro area was the industry wasn't going to be in the city anymore, and the city would be more of a white-collar place. The Bronx lost hundreds and hundreds of businesses. Once you didn't have businesses, then you've lost a tax base, which means that you don't have the money to sustain all the stops on the number six train, and so you would just close some of those stops.

Disastrously, they did it by closing firehouses. They closed firehouses right at the time that the fires were starting to get really bad. This was a time when there's still half a million people living in the South Bronx. I mean, like 400,000, so it went through a really tough period, and people assumed that that was something about the people who lived here and about the place. It wasn't about that. It was about decisions that had been made elsewhere. "Well, that place, we can sacrifice it," and that was more or less what happened here. It gave the Bronx a bad reputation and an undeserved reputation.

It's a place where a lot of poor people live. It's a place where people live when they're starting out. For the city to do what it does, which is to make immigrants into Americans, there have to be places where you can start where you don't have to have a lot of money. You do have a lot of people with precarious lives live here, and that makes for all lots of different difficult social situations, but the Bronx is successful, I think, at bringing people into the city and being a place where lots of different people can live.

Zach Helfand: Our route on Sedgwick Avenue has morphed from this kind of underbelly, under all this infrastructure, a nowhere zone. All of a sudden, it becomes residential, pleasant, these high-rise buildings with these nice river views. Okay, where are we now?

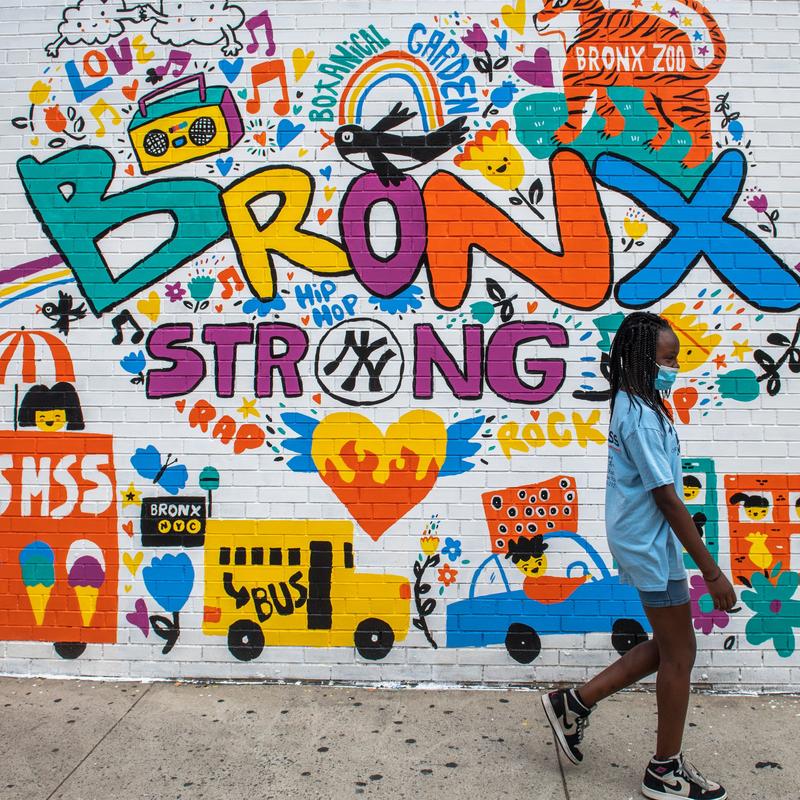

Ian Frazier: Well, we are at Cedar Playground, and this is where some of the early hip-hop jams took place as early as 1974.

[music]

Zach Helfand: It's kind of hard to imagine from the bench where Sandy and I are sitting, but if you know anything about the beginnings of hip-hop, you know that one of its creators was a man named Clive Campbell, also known as DJ Kool Herc. This was his stomping grounds. This is where he was doing the creating.

Ian Frazier: What Kool Herc would do is bring his massive amplifiers here, and they would plug into the streetlights. These amps were so powerful that when they got really cranked up, the streetlights would go dim. There is a description by Grandmaster Flash in his book, The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash, where he talks about coming here because he's heard about this. This is in May of 1974. He comes here, and he says he could hear it thundering blocks away. When he gets closer, he says that it was not only the loudest music he had ever heard, it was the loudest sound he had ever heard.

Zach Helfand: There's so many sounds in the book. There's dynamite, fires, cars, horns, train whistles, cannons. This was a different kind of sound, but almost kind of a reaction to some of those sounds, in a way.

Ian Frazier: Yes. I see it as a reaction, and I see it as what it is based on. What is it based on? It's based on the heartbeat. It's like, "We're still here." It's just that it's a really powerful sound. It's kind of like, if you ever hear the song South Bronx by Boogie Down Productions, that's like a war cry. It's just like South Bronx, South Bronx, South Bronx, South Bronx.

[MUSIC -- Boogie Down Productions, South Bronx]

Boogie Down Productions. South Bronx, the South-South Bronx, South Bronx, the South-South Bronx, South Bronx, the South-South Bronx, South Bronx, the South-South Bronx. Many people tell me this style is terrific. It is kind of different.

Ian Frazier: If you see what you're looking at, you're looking at all of this. There's the Major Deegan, and beyond that are the railroad tracks. Beyond that is the river as you're looking west. This is just blasting to the skies. It's not surprising that music that began with that kind of an environment would go around the world. I mean, you could practically hear it around the world. I like to think that, like, some of the jams where they did it over on the Taft High School playing fields, which are just wide open, that you could see them from space. These are important moments, and I consider it the Bronx's response to all the infrastructure that we were seeing. Just powerful machines came here and plowed and tore down and bulldozed and crushed, and then the Bronx answered back with hip-hop. That's how I configured the beginning of hip-hop and why I think it's got a real heroic element to it.

Zach Helfand: By now, what had looked like just a little bit of drizzle was starting to get more serious, so it was time to wrap it up.

Ian Frazier: It is pouring, I would say.

Zach Helfand: Yes, out of nowhere, it's. Well, the thunder was a clue.

Ian Frazier: The thunder was a clue, but it did look like it was going to go that way, but it didn't.

[music]

Zach Helfand: Do you plan on continuing your Bronx walks now that the book is done?

Ian Frazier: Probably not. I'm like an actor who plays a role, and then I'm on to the next. I'm sorry, but I feel such an attachment to it and I'm so happy to have the geography of the Bronx in my mind because it's a complicated geography. I'm really happy at the people I met here, the people that I went on walks with here. Those people, I want to continue to go on walks with my friends here, but probably I'll move on to something else.

David Remnick: Ian Frazier's new book is called Paradise Bronx, and you can find so much writing by Ian Frazier@newyorker.com. humor, reporting, and so much else. He spoke with editor and writer Zach Hellfan.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.