Judith Butler Can’t “Take Credit or Blame” for Gender Furor

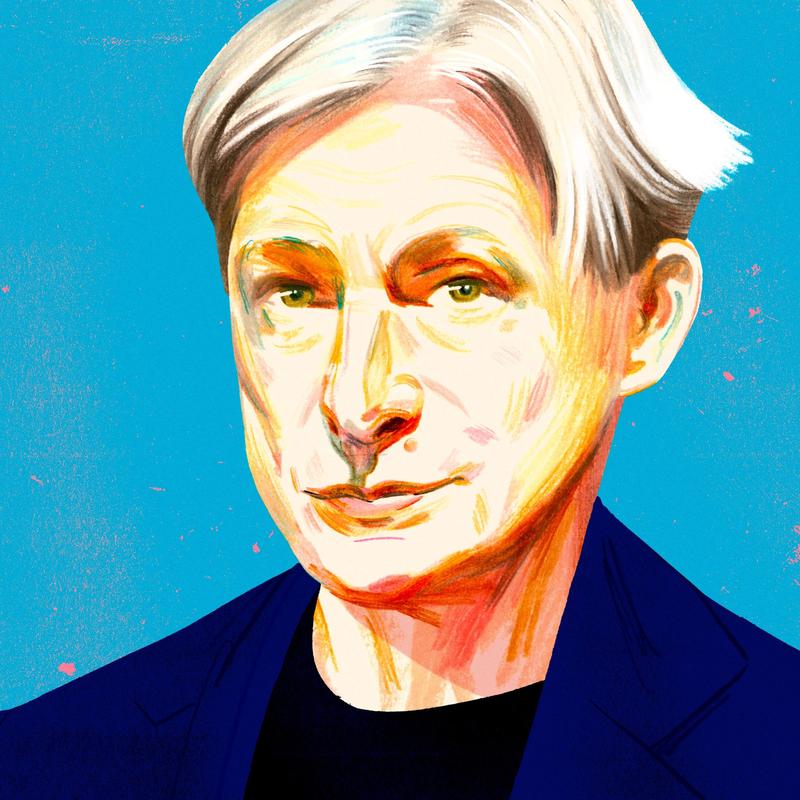

David Remnick: Now, long before gender theory became a real focus, a real target for conservative lawmakers, it existed largely within academia. If you were interested in gender, one of the people you were definitely reading was Judith Butler. Butler is a philosopher, and in 1990, they published Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. This is a crucial book. It began popularizing the idea that gender is a social construct or a performance to use Butler's terms. In that view, gender is not just a matter of biology, but is determined by a set of behaviors that are learned as part of culture.

Those ideas of Butler's proved extremely influential and are now widely held by a younger generation of Americans, whether they've read Butler or not. Those ideas are also furiously contested by major conservative political forces around the world, from the Vatican to Vladimir Putin. Judith Butler addresses that backlash in a new book called Who's Afraid of Gender? Professor, an important part of any philosophical or political discussion is defining terms. What would the definition of gender be in the context that you are using it?

Judith Butler: Well, in general, I would say that gender is a way of organizing society. We start with a general question like, "How is gender organizing public life, healthcare, education?" Then we go about trying to understand it. Sometimes we start with a binary notion of gender that is an assumption that there are only two genders. Of course, what we then discover on the basis of that hypothesis tends to be that there are two genders [chuckles]. Sometimes we have to open up the hypothesis in order to see the mosaic of gender differences and the complications that have been introduced by the consideration of third genders or neutral pronouns or other kinds of categories that seem to describe better how people understand themselves and how they present in society.

David Remnick: One of the central concepts of your book, Gender Trouble, again, 1990, is the notion that gender is in many ways performative. That's a crucial word in that book. What do you mean by that and what was the state of play of the discussion that you were responding to when you published that book in 1990?

Judith Butler: Performativity was a concept that interested me, but it's hard to talk about now, because when people say something is performative now, they mean it's fake. It's just a show.

David Remnick: Right. That it's put on.

Judith Butler: That it's put on or empty. That was not my meaning at all. At first, I tried to correct people like, "No, that's not what it means." [laughs] Of course, it's totally out of my control. It's out of everyone's control. It's hard for me, because then people think, "If gender is performative, it's all show," but of course, it's not. All I meant to say was that we enact social norms in and through our body and our ways of comporting ourselves in this world, and that these social enactments that we're involved in, in a daily way, come to constitute our sense of who we are as a gender.

David Remnick: People in their teens and their 20s seem to have a markedly more complicated view of gender. Yet, I mean this with respect that very few of them are likely to have read Judith Butler's books in middle school or in high school, and yet ideas like yours somehow seep into society to some degree or another. To what degree do you feel a sense of responsibility for that?

Judith Butler: I don't think I can take credit or blame [laughs] for all that young people are doing with gender these days. You have to remember, there's a lot of gender play in the media. There's a lot of gender discussion online. There are many people who've written on gender. I was not in any sense the first. I also described some of what I was seeing in social movements and in gay, lesbian life.

David Remnick: Something central in your book is the role of the Vatican, the papacy, and also the church hierarchy when it comes to gender. Why is that so crucial?

Judith Butler: Well, the anti-gender ideology movement can be dated back to Joseph Ratzinger's work before he became Pope.

David Remnick: He became Pope Benedict and became co-Pope for a while, too.

Judith Butler: That's right. He became alarmed by the theory of gender because he understood there to be a natural law that established men and women, both as different from one another and as situated within a hierarchy in which men were supposed to be doing certain kinds of work in the world and women had domestic and reproductive functions to fulfill. There's a creationism, we might say, that the Vatican was defending over and against gender ideology.

David Remnick: Does Pope Francis differ from Benedict?

Judith Butler: Pope Francis has been so much more progressive than his predecessors, certainly has said--

David Remnick: To the agony of much of the Vatican.

Judith Butler: Yes, to the agony of the Vatican, he certainly accepted homosexuality more fully. At the same time, he's distinguished between two forms of feminism. He says there's sexual difference feminism that accepts that the human always comes in a complimentary fashion. There's a male and a female. Then there's a gender feminism, he says, which seems to think that you don't have to be either or that whoever you become in this world, man, woman, or something else, is not necessarily based on that natural distinction.

He was clear that gender was a diabolical force and even at one point, says that we should think of Hitler Youth when we think about gender or an atomic bomb. In other words, not just Pope Francis, but the evangelical church as well, especially in Latin America, has produced a notion of gender as a demonic ideology that has to be expelled from this world. This phantasm, this demon, this is being used to put fear into the hearts of people, to make them flock back to the church, its authority, but also to authoritarians who are very often fed by this kind of anxiety and fear.

David Remnick: The title of your new book is Who's Afraid of Gender? I see that fear all around me politically, large and small. For example, I have a deep interest in things Russian and I follow the pronouncements, and many of them are horribly scary, by Vladimir Putin, and he uses in ways of asserting difference from the West, a newly Christian conservative Russia, and part of that is that gender is seen purely traditionally and that he's mocking about the notion of there being an unlimited number of genders, and he plays with this. What is he reacting to?

Judith Butler: Let's remember that when he says, "Oh, these gender ideologists will take your sex away from you, or you won't be able to call yourself mother or father," he's actually saying something in the exact same words, as a number of other leaders, mainly authoritarians, who have decided that gender is a threat to the nation, to the natural family. Gender has become for him something of a phantasm, quite frankly. Obviously, nobody who is thinking about gender or uses gender in their work or their policy or their politics is saying, "You can't be a mother, you can't be a father, and we're not using those words anymore, or we're going to take your sex away." No, no one is saying that at all.

David Remnick: As I understand it, you decided to write this book, Who's Afraid of Gender?, after an incident occurred in 2017 in Brazil. Can you describe what happened there?

Judith Butler: I was part of a conference on the future of democracy, actually, and we were at a community center in Sao Paulo, and I was told that there were people gathering outside who did not want me to speak and who in fact wanted me to leave the country immediately. I was sequestered in a room. I saw, at least through pictures, that they had burnt me in effigy outside, and that there was a fair amount of, well, political hysteria, frankly, saying that they were against gender, the ideology of gender, that they were against pedophilia. Somehow, gender was associated with pedophilia, which was new to me, I had never had that before, and that I would destroy the family and I would indoctrinate or seduce the children.

David Remnick: Your book is--

Judith Butler: I'm not going back to Brazil, even though it has a government and there are a lot of wonderful people there, but I won't go back.

David Remnick: Because you think that you'd be in danger and enough is enough?

Judith Butler: Well, those people are still there. They're in the minority, but they're still there.

David Remnick: Your book explains the importance of sex in legal frameworks, like the Supreme Court's decision to extend discrimination protections to include gay, lesbian, and trans people. Why make the distinction between sex and gender on a theoretical level?

Judith Butler: I used to make that distinction more than I do now. It turns out that the act of sex assignment itself, which takes place in hospitals or according to legal authorities, that that's already a way of socially organizing who we are. Maybe gender is happening at the very beginning. We're being gendered.

David Remnick: Isn't biology organizing the way we are?

Judith Butler: We take into account biology when we give a sex assignment. That seems right. There are also a set of exceptions to binary divisions. I'm not against sex assignment, don't get me wrong. I'm not against it at all. I just think people should be able to assign themselves a sex later in life. I don't dispute biology, but an infant can be assigned a sex on the basis of perceived biological differences. That makes sense. I don't have anything against that. If we think that that has to stay the same through all time, then we might be making a mistake.

David Remnick: This is not a discussion that's limited to authoritarians and people on the far right, as well. Even in liberal communities, wherever they might be, parents who think themselves very hip and up-to-date and politically progressive suddenly come home and they're told that in their kids' classes, that a lot of the kids in the class will identify, again, a term that might be new to them after all these years, they identify in ways that they would not have anticipated. A large number of kids in the class. How were they meant to think through that?

Judith Butler: Well, I think probably with interest and compassion, that would be a good start [laughs].

David Remnick: Their job is to love their kids, there's no question about that. As the song goes, "Something is happening here, but you don't know what it is." What is it? How general is it?

Judith Butler: It ain't exactly clear.

[laughter]

David Remnick: That's the other song.

Judith Butler: Yes, there's a revolution in the elementary school.

David Remnick: Do you mean that? If so, what's the nature of the revolution?

Judith Butler: No, I don't think it's a revolution, really. I think that so many kids have conformed to gender norms quickly and with some fear. We know that in non-supportive environments, kids can suffer a lot. I think if they seek to change their identity, if they seek to call themselves a non-binary, or maybe they want to take on a new gender altogether, they're trying to say something. What are they saying exactly? They're trying to say that living under certain kinds of constrictions is not okay, that they can't live that way, and that they need room to define themselves.

Now, I don't know, it seems to me we have to listen closely to kids who say that and stay with them, stay close to them. I think there's nothing more important than having an exploratory period of life where you're allowed to play and decide how you want to play and in what way. I think there's so much parental anxiety, that it sometimes ends up being repressive, it shuts down the conversation, or it accelerates it in a way that's probably unnecessary. Maybe we just need to spend more time with kids, listening to what they're trying to tell us about who they are and how they want to live, and what's livable for them.

David Remnick: I read an interview with you in the Financial Times. The reporter was pretty much freaking out about the notion of pronouns, and he was going to get the pronoun wrong or right, or whatever it was, and only in recent years have you started using 'they' and 'them' pronouns. What was that decision like for you? How important is this, I think, detail in the entire discussion of gender?

Judith Butler: It is sometimes extremely awkward to have to relearn someone's pronoun, especially if you've known them your whole life. If that person asks you to call them by a particular name or pronoun, they're asking for some recognition about who they are and how they feel, and how they want to be addressed in this world. It's one of the few ways we have of saying, "Treat me like this, please. If you want to treat me well, if you want to treat me with respect, then please accept the pronoun that I use for myself."

I think it's a basic question. I remember in the Black Power Movement, and even in the Civil Rights Movement, there were major discussions about how Black or African American people should be referred to. There were always people who said, "Oh, why do I have to relearn? Why do I call them this?" White people who were in a state of resistance, and they were bothered and it was frustrating, or in the feminist movement somebody wants to be called a woman rather than a girl and people complain. Why do I have to change my practice?

David Remnick: Yet in this interview, you were very forgiving and good-humored about this guy's anxiety, but underneath that, does it anger you when somebody screws it up?

Judith Butler: No, it doesn't anger me unless somebody is trying to do it on purpose in an effort to put me back in my place, or just deliberate refusal of recognition. That's like, "Oh, why is that person doing that? They actually know." I do. I struggle. I err. I find it difficult to always keep clear who wants to be called what and I have to ask people and sometimes I have to ask them a couple of times. Especially as one gets older, one has to ask many things [unintelligible 00:16:37].

David Remnick: Let's not discuss that.

[laughter]

David Remnick: That's for another day if we're still around.

Judith Butler: I think we should be compassionate about people who err. I don't want to become the police. "I'm not called that. You've misgendered me. Don't do that again." I will gently say, "Yes, I do prefer that." I think the young people gave me the 'they'. Maybe I helped to give it to them. I have no idea.

David Remnick: How do you mean?

Judith Butler: Well, because it's a non-binary. It's a position outside the binary. At the end of Gender Trouble in 1990, I said, well, why do we restrict ourselves to thinking that there are only men and women? Maybe there's some other kinds of genders. This generation has come along with the idea of being non-binary. It never occurred to me. Then I thought, well, of course I am. What else would I be? It fits perfectly. I just feel gratitude to the younger generation. They gave me something wonderful. That also takes humility of a certain kind, like, okay, I'm an older person who needs to be called by this now and wants to be, and I like it. It seems right.

David Remnick: You use the word phantasm throughout the book, which I read as a notion of a dark fantasy that's created by and aroused in certain people about gender. Could you explain it more specifically?

Judith Butler: If we look at the charges made against gender, that it will indoctrinate or seduce young people, that young people will read a book and see an image and then they will become homosexual or they will want to change their sex or they will-- as if they will somehow be contaminated by this thing called gender.

David Remnick: Brainwashed, yes.

Judith Butler: Sometimes it seems as if they oppose the freedom itself that they associate with gender. The cluster of fears around gender are not always internally consistent with one another. I think many people do believe that their sex assignment is given from God or that it's natural and that everybody has one and that there are only two in the world and that fact is universally shared. When your idea of natural order gets challenged by new ways of thinking about gender and sexuality, it can be very frightening for people.

David Remnick: I fear that it works. I fear as a matter of politics that it's easier for Donald Trump to go on about a trans swimmer than it is about tax policy. It's a more electric gathering the base strategy.

Judith Butler: It is true but my sense is that Trump watched DeSantis try to use gender and race to scare the people of Florida, but also in the United States more generally, and he saw that it wasn't quite working [crosstalk]--

David Remnick: Is this because DeSantis is bad at it and Trump is better at it?

Judith Butler: [chuckles] I think that Trump decided that anti-migrant discourse works better. I think if you count how many times he'll say something about migrants versus trans people, you'll see that the anti-migrant discourse is for him more promising as a way of stoking fear, but it is--

David Remnick: An ugly contest.

Judith Butler: Yes, it's the same method.

David Remnick: I don't mean to change the subject too abruptly, but you are engaged in any number of other political arguments over time. I want to set the record straight here because it seems to me there's a lot of confusion about this. You originally described what happened on October 7th in Israel as an armed resistance, saying that it was "not a terrorist attack, and it is not an anti-semitic attack". You later described October 7th as a terrifying and revolting massacre. Have your views on that attack changed over time? I just want to give you a chance to set it out.

Judith Butler: Oh, well, I think it's the other way around. I publish something in the London Review Books.

David Remnick: London Review Books, right?

Judith Butler: I did certainly condemn Hamas and described just how anguishing it was to see the massacres that occurred on October 7th. As a Jewish person, my first feeling and my continuing feeling is that the atrocities committed by Hamas are certainly not justifiable. They should be condemned, and they remain appalling and anguishing to me. Nothing in my view has changed.

David Remnick: Did it change your view-- I'm sorry to interrupt--

Judith Butler: Yes, go ahead.

David Remnick: Did it change your view expressed in the past that both Hamas and Hezbollah are progressive, you used the word progressive movements, which also got a lot of flak?

Judith Butler: Yes, they did get a lot of flak, but in both of those instances, we're talking about extracts from a longer discussion, that people who oppose my views circulated on the web. An [unintelligible 00:22:15] discussions, because I am someone who has published a book on non-violence and I am always in favor of non-violence, I was asking, how groups such as these can be brought to the diplomatic table.

Rather than call them terrorists, which means that they can't be spoken to, they can't be dealt with, why don't we understand what the aims of their movements are? Put them in conversation with people who are committed to a non-violent resolution of that conflict, and get them to lay down their arms. Now, that is what I said about Hezbollah and Hamas. I made that very clear, and I actually likened it to the Irish Republican Army. I said, "How did that work, such that those folks agreed to put down their arms? Who reached out to them? Who made it possible for them?"

I actually see it as an obligation of the left, let's say. You want equality for Palestinians, you want political self-determination for Palestinians, or you want Israeli Jews and Palestinians to live on the basis of equality in a single state or a two-state solution. The only way you're going to get that is through a transformation of power, the end to the occupation, and the end to the siege of Gaza and the bombardments and the forms of imprisonment that we're seeing.

I have always been in favor of non-violent modes of achieving equality and justice in Palestine. I believe that it is possible to understand something like Hamas as part of a liberation struggle with a hideous tactic, with an unjustifiable tactic. Those who are in favor of that liberation should be speaking to them and working with them, as I believe they are now, to persuade people to move to non-violent modes of reconciliation and forms of justice.

David Remnick: What is terrorism, then? Is that something that you think is a term just used as a cudgel?

Judith Butler: Well, it can be used as a cudgel.

David Remnick: Was Al-Qaeda a terrorist group or part of a liberation movement?

Judith Butler: No, Al-Qaeda is a terrorist group without any question. When we talk about Hamas as terrorist, when people call it terrorist, they're talking about the militaristic wing of Hamas and the atrocities that it has committed, but if we're going to say that it has no political aim, that it's just pure evil, then we are missing the opportunity to understand what is in that political aim that is worth retrieving and affirming and what in that political aim is not worth retrieving and affirming. I just worry that when we revert too quickly to the word 'terrorist', we no longer have a political analysis of the situation, and we're not interested in a political solution.

David Remnick: Professor Butler, thank you very, very much.

Judith Butler: All right. Take care.

David Remnick: Judith Butler is a professor at the University of California at Berkeley. Their books include Gender Trouble from 1990, and the new book, Who’s Afraid of Gender?, which addresses the global backlash against LGBTQ rights.

[music]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.