Christmas in Tehran: Bringing the Holidays to Hostages

David Remnick: Today we've got an unusual holiday story to share with you. It starts back in 1979.

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: On the 22nd of December, which was a Saturday, your mother and I had been out grocery shopping. When we returned, we found the telegram. I read the telegram aloud to her. It said something like the Revolutionary Council of Iran is pleased to invite you to conduct Christmas services with the Americans in the US Embassy.

David Remnick: That's the Reverend M. William Howard, Jr. He received that telegram as the Iran hostage crisis was unfolding. Howard was a prominent minister, the president of the National Council of Churches. He also happens to be the father of our senior producer, Adam Howard.

Adam Howard: When this came across your mail, and you're reading it with Mom, did you even hesitate for a minute, or did she raise any concerns, or reservations about you going?

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: Well, as you know, I've done some pretty daring things in my younger days. One of the things she often said when I was given invitations to go to various places like Syria or Guatemala, she would look at me and say, "Is this what you think you need to do?"

Adam Howard: During the hostage crisis, revolutionaries in Iran invaded the embassy because of America's ties to the Shah. The Shah was the country's corrupt last monarch, and he'd been propped up largely by the CIA. Now by that point, the Shah was in the United States receiving treatment for terminal cancer. The revolutionaries had vowed to occupy the embassy until the US sent him back, something that the United States was refusing to do.

Reporter: The US Embassy in Tehran has been invaded and occupied by Iranian students. The Americans inside have been taken prisoner, and according to a student spokesman will be held as hostages until the deposed Shah is returned from the United States.

Adam Howard: They had taken more than 50 hostages. My father got his invitation seven weeks into the crisis. Now I wasn't even born yet, my older brother Matthew was two.

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: Shortly after I received the telegram, it came on the news that American clergy had been invited. They mentioned that William Sloane Coffin who was leader of the Riverside Church in New York, and Bishop Thomas Gumbleton of the Roman church were going to also go.

Adam Howard: My father and the other clergymen were asked to be there because of their reputations within their religious communities, but they were also known to be progressive-minded people, which didn't hurt.

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: We agreed to meet the following day at Riverside in New York. We met and we thought about the implications of this, we began to call around and speak with people who could give us some kind of orientation. We talked with then Secretary of State Cyrus Vance.

Adam Howard: What was his perspective on what he thought was happening here?

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: Frankly, they were delighted that we had been invited, because up to this time, no American had been allowed to see the Americans that were in captivity there at the embassy. Of course, there was a lot of speculation, but no one had actually seen them. We were in no way discouraged from doing this. It never really occurred to me, and this was a striking question, a surprising question I received for many people who presumed that there was a level of risk that we might be taken hostage.

Adam Howard: I was going to ask, was that a genuine fear that you had?

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: No, I don't think either of us who traveled to Iran had that feeling.

Adam Howard: Why?

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: Number one, we'd been invited. Number two, from the beginning, there was a sense of genuine respect for the religious heritage of the hostages. A unitary-- There were people there who were Orthodox, there were non-believers, but there was a presumption that they were Christian. Remember, the Iranian government was overwhelmingly Shi‘ite Islam, and they wanted to show respect for the Christian faith. Now keep in mind that prior to that time, a lot of the public discourse, news media, they referred to these people as communists. See, they were very devout Muslims from all that I could tell before, and during this event.

Adam Howard: I didn't want to touch back on Matthew because he was about my daughter's age, almost at that time. I'm assuming he was far too young to understand any of what was happening. Did you explain to him that you were going away? Were you concerned about his well-being while you were in this pretty scary situation?

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: Well, yes, of course. I'm not recalling the exact thing that Mom and I said together. Remember, this is at Christmas and mom was responsible for assembling toys and things like that while I was away. She made me aware that she had quite a struggle getting him ready for Christmas. The interesting thing about this is that the Iranian hostage crisis was the breaking news all day, you see, and Matthew literally could watch his father on television. It didn't feel, I guess, to him that I was so far away.

[music]

At this moment, there are 50 Americans who don't have freedom, who don't have joy, who don't have warmth, who don't have their families with them, and there are 50 American families in this nation, who also will not experience all the joys and the light, and the happiness of Christmas.

Adam Howard: How concerned were you about the fact that this was probably as much a PR move as it was a genuine act of kindness?

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: Well, let me just say, I think propaganda is always part of something like this. On the other hand, we had a public that was quite riled up. Who knows what might have resulted if this issue were not somehow addressed, in other words, might there be an American invasion, an attempt to rescue the hostages in a militaristic way? Frankly, I saw this as an opportunity to reduce that possibility. This thing just kept going on and on. A lot of vigorous protests, I don't know if you would recall-

Speaker 5: I wasn't alive.

Speaker 6: -or if you may have read it-

Adam Howard: I have read it. I've seen the footage.

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: -when you read the yellow ribbons, that thing I think it was taken from a popular song.

Adam Howard: There were a lot of t-shirts with the Ayatollah on it mocking his name.

Protestors: They invaded a sacred part, the embassy, an embassy is a sacred part of any nation. That's what they invaded, the Ayatollah is condoning this and we want them.

Reverend M. William Howard, Jr.: As I recall, we went to the airport, JFK. It was evident that we were getting-- I'm not sure who was giving us this assistance, I thought maybe the airport authorities because we were taken through a private entrance to the airport and held in a very lovely private lounge, not in the normal place until our flight left. It's like you enter a situation, it's ordinary in some ways, but the gravity of it unfolds as you are in it.

We arrived in Iran. We were escorted to, I think, the Hilton Hotel and we walked in the door and there must have been 200 or more press people. It was a circus. People from the United States but from all over the world wanting to meet these clergy who were about to go into the embassy. I'm a Protestant clergyman. I'm thinking Christmas, that's tomorrow because this was in the evening of Christmas Eve. I had staff people accompany me, and one of them came to the door of the hotel, knocked on the door, and said, "Bill, you better get dressed. We have to be at the embassy at the strike of midnight. for the midnight mass." and that's what the Muslim hosts knew about the Christian. We dressed quickly, and literally, at midnight, we were at the embassy driving to the embassy from the hotel. You talk about paparazzi, my lord, just speeding cars, reporters hanging out the window of cars with TV cameras, and you're wondering, "Is there going to be some kind of-

Adam Howard: Accident.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: -accident here?" We arrived at the embassy, and the moment we arrived, and we were expected,-

Adam Howard: I would hope so. [chuckles]

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: -that's when the--

Adam Howard: That would have been awkward.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: Yes. [chuckles] We didn't surprise them. What happened at that point really became interesting. They blindfolded us.

Adam Howard: Did they at least give you a warning that they were going to do that?

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: They explained to us why we were being blindfolded.

Adam Howard: Sure.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: They weren't mean to us,-

Adam Howard: Right.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: -but we were completely at their mercy.

David Remnick: Reverend M. William Howard Jr., recalling his visit to the US Embassy in Tehran during the Iran hostage crisis of 1979. Our story continues in a moment. This is The New Yorker Radio Hour.

[music]

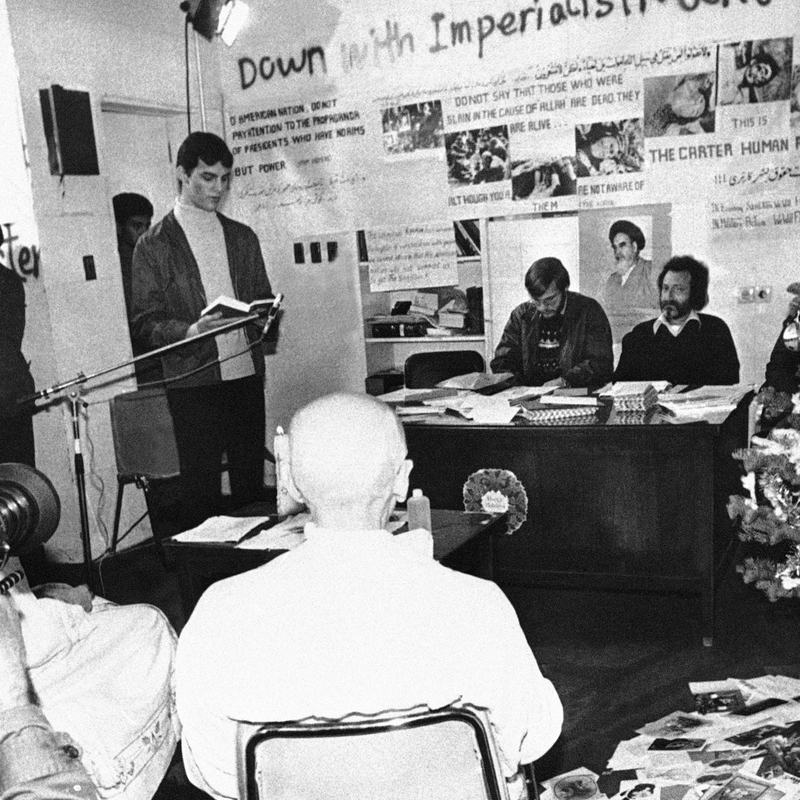

This is the New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. We're hearing a story today about the Christmas of 1979 when a young pastor traveled to Tehran during the Iran hostage crisis. At the time, the diplomatic staff of the US Embassy had been held by revolutionaries for about seven weeks. Their captivity would ultimately last 444 days. Reverend M. William Howard Jr. received an invitation to Iran by telegram, along with another Protestant minister and the Catholic Bishop of Detroit. The date was December 22nd. Just two days later, Christmas Eve, the three clergymen were ushered into the embassy to meet the hostages.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: They escorted us to a place, sat us down. Once we were inside, they removed the blindfold. Now, each of us were taken to a different location. We didn't know where the other people were, our colleagues. I was brought to a large room, well lit, and there was a table there with desserts, like cookies and cakes and so forth. That was the Muslim understanding of how Christmas was celebrated.

Adam Howard: What was it, sugar cookies and things?

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: I think it was sweet stuff. I don't know. I didn't explore it because I didn't dare eat any of it.

Adam Howard: Sure.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: I didn't.

Adam Howard: Was there a Christmas tree there and all that stuff?

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: Oh, yes. It was like what the Shi‘ites imagined, maybe what they had seen on-

Adam Howard: The movies or TV.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: -TV and movies. In walks a stream of people, obviously, hostages. Some of them were wiping their eyes and looking around. Of course, they are looking at me like, "Who the hell is this guy?" They looked as if they had been kept in maybe a place not so bright. They didn't look disheveled or abused or anything. One of the students-- and let me just say, the hostages, were taken by and held by university-age students. One of them said to the incoming people, "This is Reverend Howard. He's going to conduct Christmas services."

Adam Howard: How did they take that? Did they say--

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: Oh, with a lot of reluctance. You might say suspicion. Like, "Who is this guy?" Once they were all seated, I said, "Look, if I were in your situation, I would be suspicious of me, too." I said, in so many words, "Look, I have a family. I'd rather be at home, but doggone it, I agreed to come over here because the nation is concerned about you," and then they began to warm up because I was not kidding around with them.

Adam Howard: Sure.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: I'd said, "Look, if you don't want Christmas, we could just sit here until they come and get you." Then at some point, one or two of them would say, "No, Reverend. We respect what you're doing. What do you have planned?" I said to them, "Look, I don't know your religious affiliation, so I'm not going to come and impose my own religious tradition on you, so you need to talk to me about what your needs are." I remember very early in the conversation before anything that we might consider religious began to happen, they asked me about the NFL playoffs.

[laughter]

Adam Howard: That's to test if you're really an American.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: Are you really who you say you are?

Commentator: 11-yard line. Denver will be moving on offense from their own 11-yard line. That punt covering some 33 yards. 8:43, that is the time remaining in the first quarter. It is Denver 7, Houston 3.

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: Then, at some point, someone asked if I would offer a prayer, and we had a prayer. The prayer was a culmination of the conversation of acquaintance. It was a prayer of contrition, a prayer recognizing the need for the intervention of a divine spirit, and so forth, and so on, but it was not long.

[MUSIC - Holy Night]

My colleague, Bill Coffin, was quite the musician, and I learned later that he actually played the piano for the people he was with. There was a piano there, and they sang church hymns.

[MUSIC - Holy Night]

Well, I had no facility of that kind, but we did something that I think personally was quite affirming of the people. I said to them, "If you have, as individuals, something you want to share with me of a personal nature and so forth, pastoral counseling, if you will, I'm going to sit here and you can come over." There were a few people who came over. We talked about how they were being treated. They wondered, for example, if there was a way for me to communicate with their families and was there a way for us to make an appeal for their release. Sure enough, on Christmas afternoon, a representation of our group went back to the embassy to pick up letters that were being written by the hostages, and they were subsequently delivered to the family members when we returned.

That is essentially the first link the family members had with their relatives who were being held captive. Then, at some point, the times ended, and they were escorted out of the room. My colleagues and I eventually wound up in a common room that felt like a basement to me. The students, who actually had invaded the embassy, taken the hostages, were there. By the way, around the wall of this room were very young men. They could have been teenagers from all that I could tell, very much armed with semi-automatic rifles or automatic rifles, standing around the wall of this little room. That's when Dr. Coffin said something to the effect, "How many of these folk are you going to allow us to take home?"

Adam Howard: Now, when he said this, had he given you and your colleagues any warning that he was going to do this?

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: No, he did not [crosstalk] anything about what he was going to say.

Adam Howard: Did you think this is completely crazy what he's doing and dangerous?

Reverend M. William Howard Jr.: Well, I said right away, "Bill, it's not that kind of situation." He was associating this with Vietnam. The Vietnamese were not driven by religion. These were people of real conviction about Islam. There was a female leader of these students, and she was known in the American media as Mary. When she spoke to him very sternly, you heard the young men cock their rifles, [ka-ka] that kind of sound. I said to him, "Bill, you'd better leave that alone." He backed down right away. After that experience in that room, we also were taken to meet with the Mullahs, in the Shia tradition, the clergy or Mullahs.

Adam Howard: Did you get a sense that anybody was trying to, I hate to use the word indoctrinate, because it's so loaded, but trying to get you to be persuaded as to either the message of the captors or some other alternative perspective about what was going on to bring back to the United States?

- William Howard, Jr.: No, but let me answer that in two ways. One, the students were always clear, not appearing to try and influence us, but they were very clear about the role of the US in supporting the Shah, the presence of the US in Iran, the role of the US and overthrowing Mohammad Mosaddegh in the 1950s. They knew all of that in ways that most Americans did not, but when we went to visit the Mullahs, after visiting the Foreign Ministry, there were so many checkpoints, armed checkpoints, and it was evident at that point that we were going to visit the real power, not the government guy, but these clergy.

We were clergy, they were clergy, so we sat in this little room, I mean a little room. If a Mullah was sitting here, and I'm sitting here, our knees were almost touching. That was when they really poured out all of their suffering. Some of them were crying, they told us stories. I'll give you one really iconic story about American teenagers riding motor scooters into the mosque at prayer time, and the leaders were unable to do anything about it because the Americans were so much influential of the Shah, that the Shah would not allow anything untoward to happen to the Americans. These kids could just disrespect and so forth, and they cried. There was some guy there with one eye, and he told the story about how he lost his sight. The brutality of the Shah.

Now, we had some general knowledge of this, but this was like detailing. Now, on the image and indoctrination thing, because many people in the United States were assuming that if you guys could get in there and see the hostages, you must be a little bit biased towards these folk. That was going around. What we decided, because we got some word that the Ayatollah was going to invite us for a conversation. We had seen these conversations on the television.

Adam Howard: Really more of a dictating to people.

- William Howard, Jr.: He's telling them things, and you were sitting there quietly. We did not want to be in that situation. We literally planned our exit from the country in some forethought that this may transpire, so we were successful--

Adam Howard: I'm sure he maybe would have used it for propaganda purposes.

- William Howard, Jr.: Oh, yes. It would have been on American television before you could imagine.

Adam Howard: Speaking of American television, when you came back, obviously, there was quite a lot of press coverage, quite infamously in our family memories, you appeared on the Donahue Show. What are your memories of that, in terms of what the reception was when you came back?

- William Howard, Jr.: It was virtually every major outlet. One thing I would say especially the live shows is how uninformed the people in those audiences were about the history of Iran.

Speaker 9: I'm tired of seeing my flag burned.

Speaker 10: That's the issue. That's precisely the issue. [crosstalk]

Speaker 9: I'm tired of seeing and hearing these people killed President Carter. [applause] I'm not saying to go in and militarily take them over, but I think that you better understand that we are tired of everywhere in this world that people that we have helped, turning around and allowing them to destroy our flag, our self-image, and I for one--

- William Howard, Jr.: Oh, wow. People were angry, they were uninformed. When you put those two combinations together, man, that's a pretty dangerous combination.

Adam Howard: I wonder, when you reflect back on this, what do you think about what took place? Did this experience in any way change your perspective on the holiday of Christmas?

- William Howard, Jr.: I'm from the school of religious thought that doubts whether the average worshipper has fully understood the tradition that they claim. I think in this period of 2023, we are seeing, for example, how the void certain sectors of the American religious community is of basic Christian principles and ethics, how they behave in politics, and so forth. I knew deeply the religious significance of Christmas, of course, but I knew that Christmas had evolved into and still is an overwhelmingly commercial enterprise. It's about giving gifts. I understood that.

What I did understand in this experience was what it meant for the first time really, and you know very well that I grew up in the Jim Crow South, where there were many instances of not necessarily knowing how much control you really had in your life because of external forces, meaning segregationist and so on. It was in the Iranian hostage crisis that I understood how alone we are and how powerless we are when other people take control. Really, it's in that setting that one can develop faith. If you think you have other options, you often don't turn to faith. When you have no other options, you turn to faith.

[music]

David Remnick: That's M. William Howard, Jr., the former president of the National Council of Churches. He went on to be active in the anti-apartheid movement and was president of the New York Theological Seminary. Reverend Howard was interviewed by his son, Adam Howard, who's a senior producer of our program.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.