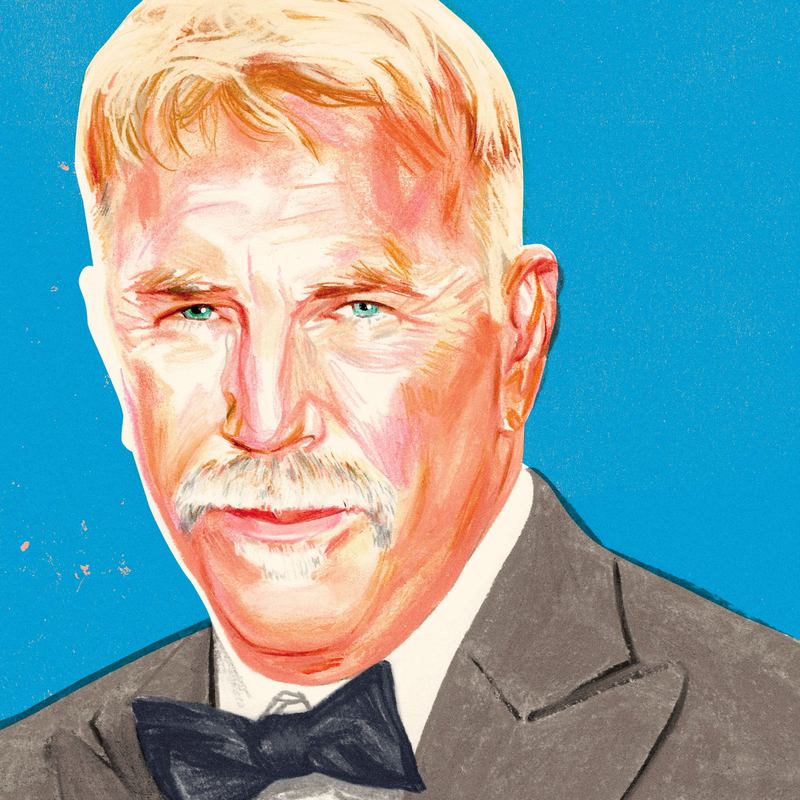

Kevin Costner on “Yellowstone,” “Horizon,” and Why the Western Endures

David Remnick: Kevin Costner has been a leading man for 40-odd years, and he's been in all kinds of movies during that time--crime, romance, drama, comedy, thrillers, baseball. If there's a constant in that long filmography of Costner's, it's the Western. One of his first big roles was in Silverado, alongside Kevin Kline and Danny Glover. In 1990, he directed Dances with Wolves, about a renegade soldier's relationship with a group of Lakota Indians. Thirty years on, Costner starred in the very successful Montana epic, Yellowstone.

[movie clip plays]

John Dutton: "You see that fence? That's mine. Everything this side of that mountain, all the way over to here, mine, too. They're trespassing."

[music]

David Remnick: All along, he's been working on a project called Horizon: An American Saga. It's a series of four films about the founding of a town in the West. The first part of Horizon comes out next week.

[music]

David Remnick: The idea for this started in your mind and on the page 30 years ago?

Kevin Costner: Yes, in 1988, I commissioned a screenplay called Sidewinder, and it was a two-hander in the Western genre. It was pretty good. I liked it. Ultimately, when it was done and I got it into a place that I thought it could be seen, there was a money difference on it. Not a big spread, but it was clearly people weren't as impassioned about making it as I was. Six, seven years passed, and I don't really fall out of love with things. I began to rethink some things, which is all our Westerns typically start with a town, right? There's a town there. We never really deal with how those buildings and those saloons and those blacksmith shops and those hardware stores.

David Remnick: The whorehouse, the bar, yes.

Kevin Costner: How did they get there? Who put that first stake in and what trouble did it cause for the people who had been there for thousands of years? Because we were putting our towns the same place that indigenous felt that it was the best place to cross a river, the best place to access water, the best-- you know what I'm saying? All the names of the famous cities we have, St. Louis, Denver, somebody was throwing a stake there and a proverbial sticking their finger in an ant hole. Of course, there was always a tipping point. In our case, always positive for us because we had this sheer amount of humanity working its way across the country in seemingly an endless numbers.

That was the fact, and the indigenous had a hard time dealing with that, and the technology that would come with each and every new wave. I started that way, and I basically took that screenplay that was in 1988, and I re-engineered four screenplays. There's actually a fifth movie sitting out there somewhere, which is the original movie where there's already a town, because I'm just as stubborn to make that one, too.

David Remnick: Tell me about another town. Tell me about how Hollywood does or does not embrace an idea from somebody who's got the stature that you have as a figure in Hollywood, as a talent in Hollywood. These things are expensive to make. It's not like my business where all you need is a pencil and a piece of paper or a laptop. What barriers did you encounter when you first decided you wanted to make this, and who were you coming up against?

Kevin Costner: Yes, it's not the first time it's happened to me. Dances with Wolves was the same thing. I did a movie called Black or White, about racism that I funded completely with a friend. Open Range, I just did it without salary. Of course, this one, I have financed a great deal of it. The industry seems to have really big years, powerful years. Off of sequels, off of the Marvel comics seem to be important. I don't feel like I'm an avant-garde filmmaker by any stretch. I make baseball movies, political thrillers, romantic comedies, and Westerns. It's not like I'm making a movie that people scratch their head about and then there's a whole group of people say, "It's really interesting."

David Remnick: [laughs]

Kevin Costner: I think I make mainstream kind of movies, but I make them in my own way. Whereas I give you some edges that maybe people don't want. Well, we don't want to see that particular scene. We don't need to see a woman bathing. We know they had to get-- Really, do you know? We don't need to see characters start to flip on us. We think they're one thing and then they're another. I'm not rushing to my gunfight is what I'm saying.

David Remnick: Do you feel that you're making a political movie?

Kevin Costner: No.

David Remnick: You don't?

Kevin Costner: Not at all. I wouldn't even conceive of that.

David Remnick: No, I don't mean about politics in Washington. I mean, a new look at how "the West was won." You're looking at it maybe from a different political vantage point [crosstalk]

Kevin Costner: Yes, maybe, but no sense of being the authority of how it was done. No sense of setting history correct. I just appreciate movies where I feel like I can lean into them because I think I feel an authenticity. I feel I just start to lean in as a picture starts to tumble like the first pages of a novel. When those ideas of landscape and language and costume and buildings don't match up with a reality, I have a tendency to dismiss Westerns. I'm not very interested in them. I find them to be our Shakespeare. If we are able to lean into this Victorian language muted by this American shortcuts, you can get somebody's intention really quickly.

David Remnick: I'm not sure I understand what you mean. You say it's America's Shakespeare.

Kevin Costner: Yes.

David Remnick: What does that mean?

Kevin Costner: I just mean the way people talk, the way Danny Huston explains Manifest Destiny. It's not a series of yep's and nope's. There are passages in there that are significant the way people talk with each other.

[movie clip plays]

?Actor: You're Apache. He thinks that if he consults the earth with enough of our dead, he'll stop those wagons coming, spoil the place. You study the newcomers. They'll look out at ever so many graves and won't make the least difference. All they see is this place is not lucky. It's just a poor bastard under it. That's what a man will tell himself, tell his wife, and they'll tell their children, but if you're tough enough, smart enough, mean enough, all this will be there someday. That's all the reason in the face of fear."

David Remnick: What are the Westerns that you admire most?

Kevin Costner: I think probably I liked How the West Was Won early up, but I was a seven-year-old, but I tied in directly to a birchbark canoe and to the high Sierras and to people dressed in skins and exotic feathers, whereas I've been watching lazy Westerns and they didn't look right. I would say that Liberty Valance was a really well-written screenplay. The Searchers was a well-written Western.

[movie clip plays]

Ethan Edwards: "I found Lucy back in the canyon. Wrapped her in my coat, buried her with my own hands. I thought it best to keep it from ya."

Brad Jorgensen: "Did they...? Was she...?"

Ethan Edwards: "What do you want me to do? Draw you a picture? Spell it out? Don't ever ask me. Long as you live, don't ever ask me more."

[music]

Kevin Costner: I think Fort Apache had a lot of really nice things in it. Rio Grande did too. There were certain dilemmas that those movies established in there that I thought they rooted me and, in a sense, they talked to me about character and, just as important, lack of character.

David Remnick: You're sitting here at a moment when you've had to pour, I don't know how much of your own money into this project.

Kevin Costner: It's significant now. It's well above-- It's well above 50.

David Remnick: Francis Ford Coppola emptied his pockets to the tune of tens and tens of millions of dollars to make Megalopolis. That's seems a strange state of affairs.

Kevin Costner: It's strange to actually pay yourself to go to work.

David Remnick: [laughs] I wouldn't do it.

Kevin Costner: Yes, exactly. Most people wouldn't do it, so I scratched my head a little bit at my own behavior. I didn't know I was going to find my yellow brick road. I wanted to desperately-- I didn't know it was going to translate into money, and it has. I didn't know it was going to translate into as much money.

David Remnick: When you would have lunch or meetings with Hollywood executives and say, "I want to do this," how did they say no?

Kevin Costner: They wish that I would do one of theirs first. I tell them everything, all the bad news. "It's this long. It's going to have subtitles," and those were bridges too far. I don't really stick to patterns, what's in style, what's in vogue, what's trending. That's not really up to me. I want to try to make something that has classic implications, which means it's not going to be judged ultimately by its opening weekend, but more by will it be revisited?

David Remnick: Weren't any of the new streaming services, which are at deeper pockets than some of the other studios?

Kevin Costner: Yes, I've gone down all those roads.

David Remnick: You've had all the lunches.

Kevin Costner: I have, and at the end, it's just a bridge too far because it's going to be expensive. You're talking about horses, you're talking about period costumes. Ultimately, I just looked at the pile over here that I had, and I thought, well, I'm not going to let that control me. I'll let that work for me, and so I decided to put that at whatever you want to call risk in order to make this.

David Remnick: How'd your family feel about putting your pile at risk?

Kevin Costner: They've seen me do that before. They've seen me push it into the middle, not blink, because I'm not really bluffing.

David Remnick: Push it into the middle poker wise.

Kevin Costner: That's right. I have my reasons I'm going to control this movie for the rest of its life so I'm not dependent. I'll do exactly what studios do. It will be exploited its entire life. Every five, six years, it's relicensed around the world. It will be sold to those same streaming services, but the difference is that money won't go missing in the accounting. Will I claw my money back? The hope is that I will. Will I make a lot of money? Anybody listening, yes, I hope so. I hope I'll make a boatload, but I'm not going to not do what I have a chance to do. I don't think I would feel very good about myself.

David Remnick: Does age have anything to do with that?

Kevin Costner: Not really. There is a shelf life on me playing certain parts, but I think at the end of the day, I have a relationship with an audience, and it is when they go to dark and they see a movie, I am, I want them at the end to understand, wow, I think I understood why I made that movie. I was really entertained by it.

[music]

David Remnick: I'm speaking with actor and director Kevin Costner, and we'll continue in a moment. This is The New Yorker Radio Hour.

[music]

This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. If you're just joining us, I've been speaking with Kevin Costner, who's about to release a new film called Horizon: An American Saga. It's a Western in four parts, which he refers to as 1, 2, 3, and 4. Now, the Western is an old genre. It stretches from John Ford to last week. They've come, they've gone, and there's always the big sky scenery unchanging and the politics ever shifting. Costner gave a big lift to the genre in 1990 with Dances with Wolves. The reviews were mixed. Pauline Kael ripped it in The New Yorker, calling it a nature boy movie, a kid's daydream of being an Indian. Yet it won Best Director and Best Picture.

[movie clip plays]

John Dunbar: "There's nothing for you to do out here."

Major Willard Grace: "Are you willing to cooperate or not? Well, speak up!"

John Dunbar: [Lakota language]

Major Willard Grace: "What's that?"

John Dunbar: [Lakota language]

David Remnick: Once again, Costner is at the center of a surge in the Western. He starred for four seasons on Taylor Sheridan's hugely popular Yellowstone, playing the taciturn rancher, John Dutton. There's now a whole universe of Yellowstone spinoffs. I'll continue my conversation now with Kevin Costner.

Tell me about your involvement in Western. Some actors embody Westerns, they do their own writing. Is the secret out that you do your own writing?

Kevin Costner: Yes.

David Remnick: How hard is that? It looks like it hurts tremendously.

Kevin Costner: No, it doesn't hurt, but I don't consider myself an absolute cowboy, though I know guys that really ride well. I never pretend. I don't pretend that I've won a medal of honor either, but I played characters who had. I don't pretend to be things. What I can play--

David Remnick: Have you seen that happen in Hollywood where the actor begins to think that he or she is that-

Kevin Costner: I'm not sure-

David Remnick: -persona?

Kevin Costner: -but I can see how somebody could be seduced into thinking that they're that smart, they're that brave. I'm always suspect of everybody who's certain how they would've done on D-Day.

David Remnick: In terms of the native of characters, the Apache community that's depicted here, how do you feel that you did this differently than say in Dance with Wolves?

Kevin Costner: I don't know that I did. Characters are different, but as human beings, they're the same. They are confused by the giant population that continues to roll towards them, and they think of it as unbelievable. What stands behind the people who kept coming were millions. They couldn't conceive of it. We catch them at the point of-- at their most confused. These people keep coming. It's also, they put their tents up at a point in a river that they no longer can now cross. It's happened a million times out there.

Not one where we shut things off to an a way of life. What did it do? Well, because they had technology down there called rifles, they had to go this way or that way. They couldn't go across anymore. Of course, when they went this way, what happened? They would run into their neighbors that they had established natural boundaries a long time ago. What we did is because we built a bridge here, we threw their life into chaos. We threw them into contact with people they'd already worked things out with. We were a mess. We were a wrecking ball for 200 years, 300 years out there.

David Remnick: What do you think we owe indigenous people in this country?

Kevin Costner: Well, it's clear that when we fly over the land and look down, and most of it's not inhabited that we didn't need all of it, did we? There's giant 30,000 acre farms and things like that that exist and what do they have? What did we lose? Think about that. This beauty-- how did they become an inconvenience in their own country? They had their own religion, their own way of life, they had children.

I don't know what I owe them, but I do if I put them on film to give them dignity, to give them high levels of confusion, to have their wives be smarter than their husbands, or more direct. I want you to see a full formed human being. I want you to see a father who understands that two children are wildly different.

David Remnick: Tell me about the difference in your feeling of ownership of a project when you're the lead actor in something, and when you are doing something as with Horizon, where it is your project. In Yellowstone, for example, you are incredibly prominent, but you're not writing the script. To what degree does it feel like yours as opposed to a project like Horizon?

Kevin Costner: Yellowstone?

David Remnick: Yes.

Kevin Costner: Well, I don't consider it mine. I consider it's something that I identified with and helped sell long before anybody else saw it. I'm really never surprised-- I'm never surprised if something's good. I'm kind of surprised when something blows up commercially, but I would hate to have a career where I did something I didn't think, gee, people liked it. Some things that haven't performed well at the box office, Water World is beloved around the world and continues to make money, but journalists won't admit that. They won't talk about that.

They won't act as if that thing hasn't made tons of money. They want to insist on a narrative that they do, but I knew at least it was good. It has stood the test of time for even younger audiences who found it, who understand. They see something that's not just filled with CG. That's me flying around.

David Remnick: [laughs] You ever see a film that you think is close to perfect? Not yours, but something that you admire so much as a model?

Kevin Costner: Yes, I do. I think The Wizard of Oz is a perfect movie. I think Giant is a perfect movie. I think Sand Pebbles is a perfect movie. I think Cuckoo's Nest is a perfect movie. They don't run a gamut of things. I think Cool Hand Luke is a really wonderful movie.

David Remnick: Do you care about critics?

Kevin Costner: Do I care about them? I don't know them really. I've had critics be incredibly nice to me and be incredibly vicious. I choose to just not-- I don't have reviews brought to me because my friends will--

David Remnick: You avoid them?

Kevin Costner: Yes, I just avoid them. My friends will go, can you believe what he said? I go, it just ruined my day. I wish he wouldn't have said that or she said that.

David Remnick: Do you feel like some sense of vengeance is mine when something turns out to be a--

Kevin Costner: Not really.

David Remnick: Pauline Kael was really nasty about-

Kevin Costner: Yes, she was cruel.

David Remnick: -Dancing With Wolves.

Kevin Costner: No, she was not nice. She was cruel. She was flip with the risks that I took, and so I dismiss her and forgive her at the same time. She was very cruel with her power, but I've had some other people really talk well on behalf and see the things that the film is going to be, but I can't be looking over the table to see what they say.

David Remnick: Off your shoulder.

Kevin Costner: I'm only trying to make three. I wish somebody make a movie like this for me. This is the kind of movie that I like to lean into and not know where it's going. I think we know too much about our movies. It used to be the curtain opened and you just leaned into a movie or you didn't based on the storytelling technique.

David Remnick: You're turning 70 this year. I turn 65. I don't like it. How do you feel about getting a little bit older?

Kevin Costner: You'll get smarter.

David Remnick: You think?

Kevin Costner: You'll be all right.

David Remnick: All right. How does it affect you?

Kevin Costner: You're going to just realize it. [crosstalk] What are you dealing with?

David Remnick: How does it affect your work?

Kevin Costner: I don't know that it does. There's some parts I can't play anymore. Could I fall in love with a young woman or a young woman fall in love with me or for me to fall in love with a woman my age and have that romantic thing take place on the screen and not spin anybody out? Only if it's done properly, only if it's done well, only if it's done with the nuance of behavior, and you could understand how that just happened.

There's these generalizations, and you get by every generalization in life. If you're willing to understand that there are circumstances, and if you're willing to put circumstances, character into your movies, then you can pull those things off if that's what's required.

David Remnick: You spoke earlier about making mainstream films, but at this point in the modern entertainment world, is it only possible to reach a certain segmented audience, certain demographics?

Kevin Costner: No. I don't think that. I don't know what's so modern about today than 1980. I think movies, when they're working at their very best, can cut through. They can become about things you never forget. I think a movie that shouldn't have cut through, Field of Dreams, became our generations. It's a wonderful life.

[movie clip plays]

Terence Mann: "The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It's been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball doesn't mark the time. This field, this game: it's a part of our past, Ray. It reminds us of all that once was good and it could be again."

Kevin Costner: There are things in Horizon that I think will touch people. When a boy makes a decision to not go with his mother, that's real. That battle is not-

David Remnick: He stays with the father in incredible danger, and the mother stays with the daughters.

Kevin Costner: He makes a fatal mistake, but it's noble. It's what you wish your son would be, but you hate him for his mistake.

David Remnick: One of the trends is that fewer and fewer people seem to be going to the movie theater, seeing it on a big screen with other people, popcorn, soda, whatever. You worry about that?

Kevin Costner: I don't spend my life worrying about that.

David Remnick: You prefer people seeing your films on a big screen as opposed to on a laptop.

Kevin Costner: I think I do. I like that. I know it's going to be viewed as it works its way down, so I did everything I could to make sure it was going to be experienced on the big screen, which is hold out. You hold out. I hold out a long time. I don't fall out of love, and I don't give in until I hear a good reason to give in.

David Remnick: Thirty years.

Kevin Costner: Yes, but I have had a life between that, and this work doesn't represent the most important work in my life. It's just I'm treating it importantly because it's what's right in front of me.

David Remnick: It's not the most important work of your life?

Kevin Costner: I couldn't say that. Professionally speaking, maybe it might seem that way. It's the hardest thing I've ever done professionally, what I've had to put into this, what I've had to do. Clearly, it's not more important than other work. It's just important that I treated that. It was so important that I have focused on it.

David Remnick: Hollywood has been a pretty political place for a long time. I think in the general imagination and a lot of the press, Hollywood is seen as left-leaning in its politics. It was a big fundraiser the other night for Joe Biden, with Obama there and Jimmy Kimmel and all the rest. How do you fit into the politics of Hollywood? You seem fairly reticent about this.

Kevin Costner: I do. I spoke for candidates. That's not too reticent.

David Remnick: Tell me.

Kevin Costner: I spoke for Obama at one point. I spoke for Pete Buttigieg. I voted Republican for Bush and for other people.

David Remnick: George W. How do you feel this time around?

Kevin Costner: Pardon me?

David Remnick: How do you feel this time around?

Kevin Costner: How I feel, but I want to clear up your reticence-

David Remnick: Sure. That's fair.

Kevin Costner: -because that's not fair characterization-

David Remnick: Fair point.

Kevin Costner: -of what I've done. What I've chosen to do is to talk when I thought I should and sometimes are willing to. There are other times when I haven't. What I believe is in the sanctity of voting and then I believe in the privacy of voting. I also realize that what I say is used by both sides. I think probably the most poignant thing I could say about where I stand is something I saw once. I was right on the Hudson River probably 16 years ago.

I looked up and I saw a billboard. It said this year, 92 million people made a difference. They didn't vote. If you want to make a difference, vote. If you want people to appeal to your sensibility when elections are being won by a million votes or 100,000 votes, you'd be a block of 50 million, and people are going to start catering to you. I won't be used in how I feel. I don't know what your leanings are one way or another. I don't know if you even characterize them as a host, or if you think--

David Remnick: I would. Not reluctant to do so.

Kevin Costner: We might be very similar in our thinking. I know where I'm at. I know what can heal the country in its exercising your civil rights.

David Remnick: I'll ask and obviously you can answer it or not. It's your right. Do you have a preference between Trump or Biden?

Kevin Costner: I'm not going to answer that with you. I don't even know why you go there because I tried to round you out that I didn't want to be put in that particular position.

David Remnick: That's fair. Imagine having a week off. It doesn't sound like you've had one in quite a while. What do you do with your time when you're not writing, acting, producing, and obsessed with film? Does such time exist?

Kevin Costner: If I'm at home, I'm able to do a lot of things, which is see all the kids' games and go to their stuff. We spearfish. We hunt for lobsters. We hunt. I fish. We play sports. I still have three kids in high school. Then when I'm working on movies, it's tougher. I try to get back. My life is pretty pedestrian. I'm a single father now. That's different. It's put an extra weight on me that comes from having a partner and now not having a partner.

David Remnick: What's the day like when you are filming? Most people listening to this have never been on a film set, never made a movie, obviously. What's it like?

Kevin Costner: For the last month, it's been seven days a week for me. A normal shooting thing when I'm directing is about a 14 to 16-hour day. Then it goes to about a 10-hour, 12-hour day when I'm editing and when the movie's all done.

David Remnick: What's the hardest thing about it?

Kevin Costner: That the questions never end. They just don't end. People will not make too many moves without me weighing in, so that necessitates that all those questions have to be answered.

David Remnick: What are the questions like?

Kevin Costner: Do you like my hair? Is the outfit dirty enough? Do I need sweat? We're not sure where we're going to set up catering. The questions, they just don't end. Then I have the ideas of how did my children's day go? I got to find time to get to the phone for that. It's intense, and I'm lucky that I have this work.

David Remnick: How do you get a chance to think? If everybody's asking you about where does the catering set up and is my dress dirty enough and all the logistics, and I get that.

Thinking is necessary too.

Kevin Costner: Sure it is.

David Remnick: How do you do that?

Kevin Costner: Between the raindrops of everything, but I do a lot of thinking at night. The directing is you are chained and balled to that movie. You can't let go of the rope.

David Remnick: That sounds like the condition for a fair amount of time to come for this project, no?

Kevin Costner: Yes. I'm going to take a month and a half off before I go back, so my mind will swirl around that. I'll make sure that my children and I are together. More to your point, you're right. I still have a long way to go to finish to get all the way to four because it won't be complete without four. Honestly, after four, I do need to rethink my life. I do need to think that I don't need to put it all in the middle again. I do need to understand that I'm not going to define myself by the movies and by the ones I'm doing or not doing. I need to figure out how to have more fun.

David Remnick: At 70, but later.

Kevin Costner: You're so concerned about age.

David Remnick: Yes, you're goddamn right. [laughs]

Kevin Costner: You're right. I've been trying- to tell you, smarten up, you're okay. You're in good shape. My mind is wide open to the possibilities for myself, and not just because economically, maybe those things are possible, it's just I've always felt the air of possibility.

David Remnick: I look at Scorsese, who's in his mid-80s, and he's got five projects ahead of him.

Kevin Costner: Right.

David Remnick: Is that the way you look at it?

Kevin Costner: Well, I've collected at least that many. Will I do them? I don't know. That's part of my thought process. Not everybody gets to land on that yellow brick road. We just trudge down things and hope that we can step on it. I was certainly not a person aware of what my destiny would be, only that I desperately wanted to find something that held my attention.

David Remnick: You feel lucky?

Kevin Costner: Something that I could work 16-hour days and not know.

David Remnick: You feel lucky?

Kevin Costner: I do. Do I feel like I haven't been bruised? I don't.

[music]

David Remnick: Kevin Costner, thank you.

Kevin Costner: You're welcome.

David Remnick: Kevin Costner is the star of dozens of movies, and recently of Yellowstone on Paramount. He won the Oscar for Best director for Dances with Wolves in 1991. The first film in his series called Horizon, comes out next week.

[music]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.