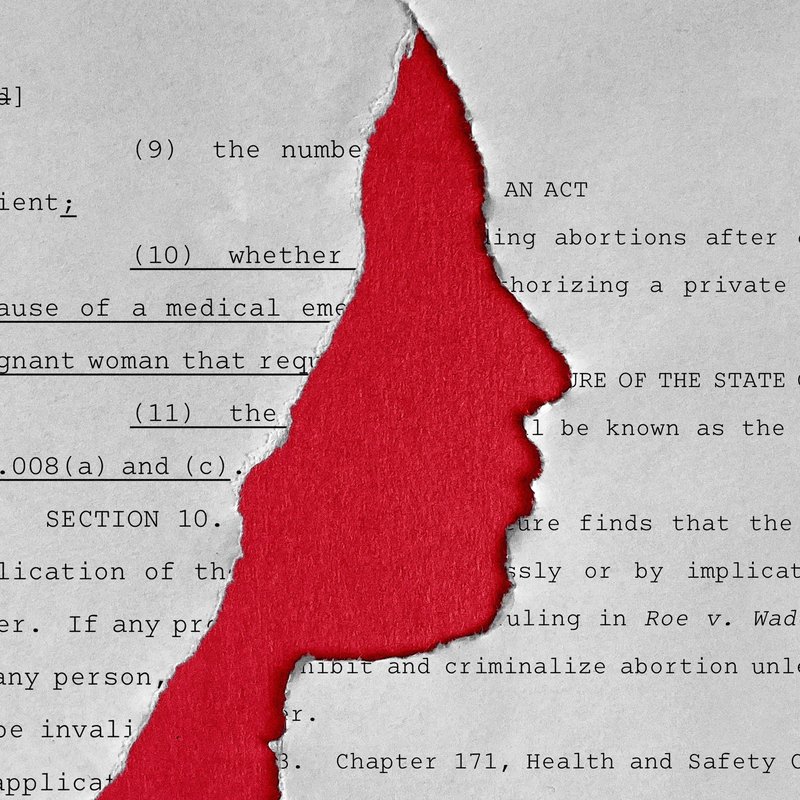

How a Republican and a Democrat Carved out Exemptions to Texas’s Abortion Ban

David Remnick: Even before Roe v. Wade was overturned, Texas had one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the country. After Roe fell, Texas went further with multiple laws that made nearly all abortions illegal.

Reporter 1: We'll take a look at this crowd, thousands are here at City Hall for the Houston Women's March here for many issues, but the biggest being the fight for abortion rights.

Reporter 2: As the mother's health is also deteriorating, and doctors have told them in this situation, most would choose to terminate the pregnancy. However, under Texas law, that is no longer an option.

Reporter 3: Emotional testimony from women in a Texas courtroom today saying the state's abortion ban put their lives in danger.

Woman: I had just been given the worst news of my life.

David Remnick: Stephania Taladrid has been reporting for the New Yorker about the abortion fight in Texas.

Stephania Taladrid: A woman has to be, and I'm going to cite the law here, "At risk of death or of substantial impairment of a major bodily function."

David Remnick: That exception is not at all clear cut, and doctors who were threatened with all kinds of penalties very often don't know what to do. Two lawsuits have been brought against the state of Texas by women for injury after they were denied abortions. Stephania Taladrid cited the case of a woman with cancer who couldn't receive chemo or radiation treatment because of her pregnancy. Cases like those led to an unlikely collaboration between two Texas legislators, one, an advocate of reproductive choice and another who helped write an abortion ban.

Steph, you've been reporting in great depth on abortion and anti-abortion bills since before the Dobbs decision. You talked with a state representative named Ann Johnson, who comes from Houston, and she was instrumental in this.

Stephania Taladrid: The first thing that you should know about Ann Johnson is that she's a democratic member of the House in Texas. She was elected in 2020, and she represents the medical center in Texas. It's home to some of the largest and leading medical institutions in the state. Not just the state, but the country really. After Roe was overturned, the message that Johnson was getting from doctors was, "I'm out of here." A violation of the law could result in a first-degree felony charge with the prospect of a very substantial prison sentence and the fine of at least $100,000 and the loss of a medical license.

You can imagine that doctors were pretty much weighing in their own livelihood against their patients at this point. Older doctors were considering early retirement, young--

David Remnick: Some would leave the state too, right? Instead of [unintelligible 00:02:51].

Stephania Taladrid: Absolutely. Anecdotally, we have heard that a great number of physicians have left the state. In particular among younger physicians who were right at the moment where they were considering whether to even begin a practice in Texas. It was easy for them to say, "I'm just not going to do this. I'm not going to expose myself to this criminal and civil liability that comes with the law."

David Remnick: Let's listen to a little of your conversation with Ann Johnson.

Ann Johnson: There's just a differing perspective on what choice means, as I meant. I would talk to a pro-life person, I would give them a complicated moral scenario, and like, well, that's not an abortion. Actually, it is. The fact that they have the ability in their head to say, "No, no, I see a distinction when posed with the risk."

Stephania Taladrid: For conservative members in the House, abortion meant termination of a healthy pregnancy. When Johnson would come up to them with conditions like a premature rupture of membrane, which is a ver fairly common complication of pregnancy that doctors talk to her a great deal about. They would say, "Well, that's not an abortion." There was a question of semantics there that needed to be addressed.

What a lot of the doctors have been saying, and women have publicly said too, is that the languages so vague and the penalties for doctors are so steep. It's been widely documented that doctors and hospitals and administrators and lawyers within those hospitals have been either delaying or denying care to women in critical conditions.

David Remnick: You've been reporting on a law in Texas that was created because of this reality, because of situations like this, and this was a bipartisan effort. What does this law do and what does it not do?

Stephania Taladrid: The law is what's called an affirmative defense and view a little bit of background on this. Before Johnson took office, she served as a chief prosecutor in the Harris County District Attorney's Office. During her time in the DA's office, she was representing human trafficking victims who had faced prostitution convictions. In many of these cases, she promoted an affirmative defense, which allowed courts to essentially limit the culpability of these women who had been coerced into committing these offenses.

Ann Johnson: Again, our whole goal here was not to use the language that could blow up politically. As a lawyer and being in criminal law for me that's where this came from, which was what if we create a similar avenue for the doctors. In the same way, we created for human trafficking victims. Yes, you engaged in prostitution, but you did it because, which is the defense. We created the same thing for the physicians in this respect. The goal was to take off the handcuffs that were being one, personal, which is criminal. They really felt that I could go to prison for a minimum of five years.

The financial, which is normally a first-degree felony is a maximum $10,000 fine, but they changed the law to say a minimum of $100,000. They very purposely told the doctors, "I'm going to get you both personally and financially."

Stephania Taladrid: It occurred to Johnson that if lawmakers created specific exemptions in the law, then doctors who got sued could show that the treatment that they had offered their patients was compliant with the language of the law. In other words, they could say, "I provided this care, but I did it because it was reasonable medical judgment." A lot of lawmakers, conservative lawmakers were deeply distrustful of doctors. They didn't trust them, they didn't trust their motives. This dates back to the pandemic and all the issues around the vaccines and stuff. She got her team to reach out to women who had been directly affected by the bans.

David Remnick: What was she able to learn?

Stephania Taladrid: She met, for instance, with a 32-year-old woman who had had a premature rupture. Her water essentially broke at 16 weeks. The baby was, of course, weeks from viability, and she was at risk of developing an infection. When she got to the hospital, the doctors told her that there was nothing that they could do for her unless she developed a life-threatening condition. Within days she went into labor, delivered a baby who died within minutes, and she developed a placental infection.

David Remnick: Which is something that never would've happened with Roe in place.

Stephania Taladrid: Never.

David Remnick: Steph, something really interesting about Johnson, who of course is a Democrat, ended up working with a state senator named Bryan Hughes, who was one of the architects of SB 8, the Texas law that nearly banned abortion before Roe was even overturned. How did that possibly work?

Stephania Taladrid: For those who don't know him, Bryan Hughes has a reputation of being one of the most conservative senators in Texas. He has championed a series of controversial bills, including a permitless carry bill, a bill that restricts the teaching of critical race theory in schools. He is best known really as the architect of SB 8. Early on, Hughes had written a letter to the Texas Medical Board expressing his concerns about the reports that he was seeing in the press and elsewhere about women being denied lifesaving care.

David Remnick: Let's listen to some of your conversation with Bryan Hughes.

Bryan Hughes: The consensus was that the folks we talk to, the law is clear. Nevertheless, there are hospitals and doctors and lawyers for hospitals and doctors who are not interpreting the law the way it was drafted. As a result of that, women are being harmed. Even though we believe the law is clear, we'd like to find a way to clarify it further. The dilemma is how do you do that in a way that provides you clarity necessary but doesn't have any unintended consequences.

David Remnick: He's talking about the unintended consequences of this legislation. What is he talking about there?

Stephania Taladrid: I think if you were to ask him why he did this, he would tell you that he's generally concerned about women and that the intention of the law was never to harm them. One of the things that he mentioned was that at the time when he started talking to Johnson about this, he heard from pretty influential donors who were concerned about this. One of them reached out to him and said, "My wife's really concerned about this, and I heard that there might be a way that you could address this, and I really hope you do that." I think it would be naive for us to think that he wasn't considering those concerns, that he wasn't looking at the polls.

A growing number of Texans would like to see the laws around abortion be less strict. About half of Texans say that, and so I think all of those factors came into play here.

David Remnick: Now you have two lawmakers who are on diametrically opposed ideological sides and on a very divisive issue, and then they end up co-sponsoring a bill together. Describe what the bill is and what is their relationship now.

Stephania Taladrid: HB 3058 is essentially allowing doctors to intervene in cases of premature ruptures and ectopic pregnancies, so cases, for instance, Amanda Zurawski. She suffered a premature rupture at 18 weeks, but doctors wouldn't offer her an abortion because they could still detect a heartbeat. She was sent home and ended up developing infections that permanently damaged one of her fallopian tubes.

In March of last year, Zurawski became the first woman to file a suit against the state of Texas after being denied an abortion, and there are now 22 plaintiffs in her case. What Johnson is essentially saying is that a woman in her situation today would be able to access lifesaving treatment.

David Remnick: For Johnson, this is a very limited victory, and for the women of the state of Texas, this is a very limited victory. What does Ann Johnson think about the prospects for widening that victory, for expanding it?

Stephania Taladrid: I think Johnson is hopeful that more can be done come January of 2025, which is when the legislature will be meeting again.

David Remnick: What's the next battle?

Stephania Taladrid: An exception and further clarification of the law.

David Remnick: What does that mean?

Stephania Taladrid: Essentially allowing doctors to practice their medical judgment freely as they did before the overturning of Roe v. Wade. I think the reason why she's also hopeful is because this was a pretty unconventional bipartisan coalition.

David Remnick: [chuckles] In Texas legislative history, it doesn't happen very often.

Stephania Taladrid: It really doesn't.

David Remnick: No. Notoriously.

Stephania Taladrid: On Hughes' side, he is in close touch with the Texas Medical Board and what he told us on the record was that he is watching the bill's implementation very, very closely and that he is hoping that it will resolve some of the ambiguities.

David Remnick: Do you think that was just a one-off situation in Texas, or could there in fact be a softening of the climate, now as abortion laws run into the reality of what's going on there and across the country?

Stephania Taladrid: I think there's a recognition on both parts that more needs to be done. The way that this was designed, Hughes essentially asked Johnson to put together a list of conditions that would be included into the law, and Johnson was able to put together a list of 13 conditions that dwindled down to two ectopic pregnancies and premature ruptures, and what we know is that women on a daily basis are exposed to and suffer all sorts of pregnancy-related complications that are not limited to those two. Johnson was in a difficult position because she could either have walked away from that compromise or she could have accepted it as a first step.

She's playing the long game here and she's looking at the other side and she's seeing that people who are anti-abortion, it took 50 years for them to overturn Roe v. Wade. I think she definitely wants to do more, but she's operating under a very restrictive climate in Texas. For Hughes, he has personally told me that he is watching the law's implementation and is hoping that it will resolve some of the ambiguities that it's hoping to address, but that he's willing to do more.

David Remnick: Right. This new law provides clarifications that are tiny in number. Tiny. You talked with an OB-GYN named Todd Ivey who spoke about what it's been like to practice medicine under SB 8, and I have to say, he sounds pretty distraught with the situation.

Todd Ivey: Until you had sat in a room with a woman who has recurrent metastatic breast cancer, who's having her treatment delayed because she's pregnant, or treatment plan altered because she's pregnant. Until you're in a room speaking to a family whose wife or the matriarch in this family has a recurrent brain tumor in her brainstem and can't access services because she's early pregnant. Until you walk into an exam room and there's a mother who brings her 11-year-old daughter who is molested by the grandfathers and is pregnant.

Until you walk into an emergency room and you see, or even in your office, a college girl who's been raped and hasn't told to anybody, and may find herself pregnant. Until you are in those situations, and until you are on the ground working with those things and handling those issues, whether I agree that decision or not is irrelevant. I do not need a politician in my exam room looking over my shoulder, telling me the right thing to do medically.

David Remnick: It is incredibly powerful to hear that. Is there any political movement in the state of Texas on the larger issue about overturning abortion restrictions? Because it was very interesting to me to listen to Joe Biden at the State of the Union address, say overtly that one of the goals of a second term for him would be to somehow find a way to get the Senate and the House to uphold abortion laws in the future as a matter of legislation rather than as a Supreme Court decision.

Stephania Taladrid: I think the reality is that there isn't at this time. There are a series of suits among those Zurawski's being one of them. Kate Cox's being the second suit that was filed by a woman who faced a pregnancy-related complication. Her fetus was diagnosed with a severe fetal anomaly, trisomy 18, and these are two women who have come forth and sued the state of Texas.

What they're asking for is broader than what HB 3058 does to let doctors practice medicine freely. I think to me, the biggest question is, as you said, this is modest progress. Our reporting has shown that women have died after being denied life-saving care, so the question is, what needs to happen and how much longer will women have to wait in order for something to actually change?

[music]

David Remnick: Steph, thank you very much.

Stephania Taladrid: Thank you.

David Remnick: You can read Stephania Taladrid on The Fight to Restore Abortion Rights in Texas at newyorker.com. This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. More to come.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.