The Warrior Met Coal Mine Strike is Coming to an End, But The Fight Still Continues

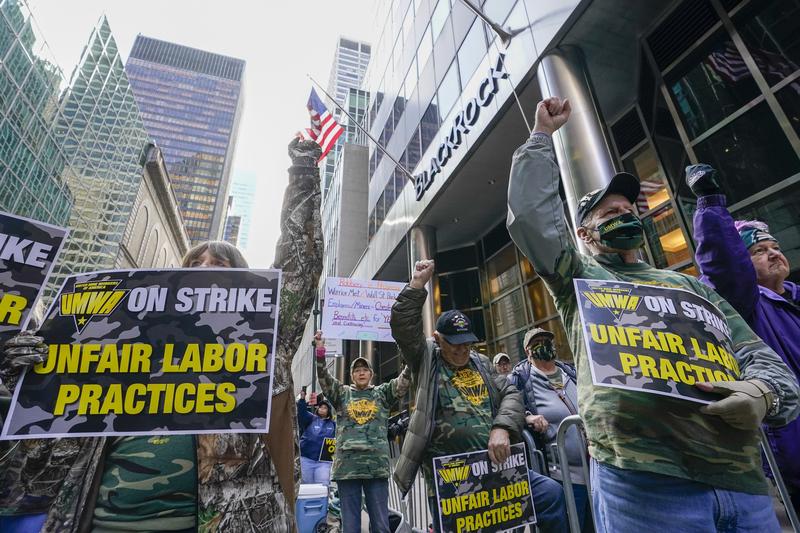

( Mary Altaffer / Associated Press )

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: It's The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry.

On April 1st, 2021, 1,100 workers from the Warrior Met Coal mine in Brookwood, Alabama went on strike for better working conditions. The miners represented by the United Mine Workers of America have been on strike for almost 23 months, nearly 700 days. This is believed to be the longest strike in Alabama history.

UMWA and Warrior Met are still at a standstill on contract negotiations while the mines are still operating with replacement workers and still earning a profit. Last week, the UMWA leadership informed the remaining members on strike that the union would be entering a new phase to win a fair contract and sent a letter to the CEO of Warrior Met announcing that the striking minors were willing to return to work on March 2nd.

Now, those coal miners who choose to return to work will be working under their old contract while the UMWA and Warrior Met continue to negotiate. For more on this, we talk to?

Kim Kelly: Kim Kelly. I'm an independent labor journalist and the author of Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Kim has been covering the Warrior Met Coal strikes since?

Kim Kelly: April 1st, 2021 is when a thousand hundred coal miners in Brookwood, Alabama, represented by the United Mine Workers of America. They walked out because contract negotiations with their employer Warrior Met Coal had essentially broken down. This is a big reason why a lot of places go on strike, right? The bargaining table turns into a little bit more of a tug of war.

They were in an interesting position because they were working on a new contract building on a prior one that they signed five years earlier when Warrior Met had bought the mines and had hired back many of the workers who were laid off in a previous bankruptcy. They told them when they came in, "Okay. We got to get on our feet. We're a new company. We're going to ask you to take this subpar contract and take a $ 6-an-hour pay cut." Basically, just sign on saying that, in five years when we're in the black, we'll give you a better contract. We'll take care of each other. That was what the assumption the miners were operating under, that this is what would happen.

Five years later, the contract negotiation start up and it's all the same. Nothing really changed. They weren't being offered bupkis, so they went on strike. Then when a tentative agreement was reached between the company and the union about a week later, I think April 8th, the membership actually voted it down. I think it was about 97%. They were not having it. I don't think anyone expected the strike to last as long as it did, but it has. Ever since they voted down that tentative agreement, the Coal Miners of Brooklyn, Alabama have been on strike up until a couple of days ago at least.

Melissa Harris-Perry: All right. We're going to get to what happened a couple of days ago, but I want to stay in the past 23 months for just a moment because I can remember the first time that you and I talked about this. We talked about it in the context of what felt like the year in labor ways that this represented a moment as you point out workers were like, "No, we're not going to take this and we don't have to take this." Particularly how coming out of or heading back to work and some level of normalcy for so many professional workers.

It was happening at the same time that folks who'd been on the front lines and at the job right throughout the pandemic were pushing back against this idea that on the one hand that they were essential workers and on the other hand were being treated in this way as though they were disposable workers. What is your sense now of what these 23 months have taught us about the power of workers or the lack thereof?

Kim Kelly: It is so interesting to see you contextualize it like that because you're right. These folks have been on strike through basically these entire two years of labor becoming more of a big deal. We're seeing all the headlines about all these workers who are taking power back and organizing and striking and protesting, doing incredible work. The movement is full of energy and it's full of-- The movement is full of movement for the first time, and I think a long time and yet there are still this group of workers, and I'm sure many other groups of workers too, but this specific group of workers who have been out on the front lines on strike throughout this entire two year period, but they got left behind. They didn't get pulled into the big rallies that we've seen in the Northeast.

They didn't get the New York Times headlines. They didn't get senators and fancy celebrities tweeting about them. They didn't get half of the attention that they needed or deserved. I think that is something, it's a sobering aspect of all this too, that the labor-friendly media isn't big enough yet. We can't cover every strike and some people are going to get left out. It's always been that in this country when it comes to major labor laws, when it comes to the rights that are bestowed on workers, someone's always left out.

In this case, I would not say necessarily, it's always been predominantly white workforces, like the one in Alabama we're talking about. In general, there's always been groups of workers that have gotten less attention, less respect, fewer rights. I think it's important to remember that too, while we're celebrating our hard-earned victories, and successes and the excitement is that there's still a lot of work to do.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Remind our listeners about some of what these workers have faced over these past two years on strike. Again, the stories you've told have been just stunning.

Kim Kelly: It is like Harlan County, USA down there [laughs]. It's been wild. I think some of the most egregious things that I've reported on and seen evidence and video of have been scabs and other company workers driving their vehicles. This is Alabama. These are big trucks driving them into the picket line and into striking workers. I know multiple people personally who have been either hit by a truck or hit by flying debris like a burn barrel, for example, that a truck drove into. That is just absolutely incomprehensible to me, though, that wasn't one of the biggest stories in the country when that happened, but it wasn't, but there it was a big deal and it's part of this ever-evolving tapestry of what's going on down there.

It's also just gotten so ugly in the way that the company has used the local judiciary and law enforcement to try and break this strike in any way they can. They've hit the miners with so many different injunctions and restraining orders, and basically, at one point the picket lines dwindled down to zero because there were so many restrictions on it. It's really been a grim scenario down there. They haven't had any support from local officials or state officials or anything of that nature. They've really been fighting it on their own and with the help of the movement,

Melissa Harris-Perry: Now, these striking workers are preparing to return to work, but without a new contract. Can you tell us what's happening?

Kim Kelly: It is definitely at a very emotional moment right now for the strikers, for everyone who's been supporting them and following the story. The UMWA leadership made the difficult decision last week to send a letter to Warrior Met CEO and say, okay, we're-- It's called unconditional offer of return to work. They're saying, "Okay, we'll send our people back."

The negotiations will continue. They're not going to cease negotiations. They're still trying to get a new contract. They need one. Right now they will be going back under the old contract, which is of course not acceptable to the miners. Essentially, they ran out of other options because one of the primary reasons this strike has not been as successful as we would've hoped, it's not the minor's fault, it's not any person's fault. It's because of the coal prices.

A couple of months after they walked out, I think it was June 2021, coal prices shot up and they've stayed high this entire time. When that means is that Warrior Met, even though they don't have their proper workforce of well-trained, experienced miners there, they've run in replacement scabs from across West Virginia and Kentucky, and they have a much smaller temporary workforce right now. They've still been able to produce and sell and make profit on that coal.

The earnings report that came out a couple weeks ago showed that they're back at 2019 levels of profit. It's almost as if in terms of their bottom line, the strike never happened. Part of that is because two when the strike began during the earlier days of COVID, the mind didn't shut down. The workers still had to go to work. They had this 2.8 million ton stockpile of coal ready to go when the miners walked out. Much of this was just bad luck and economic circumstance that really just kneecaps the strike in ways that were difficult to get over.

By the end of it, the only people that were suffering that were being harmed were the minors and their families. The company wasn't feeling the economic pinch that you would want throughout prolonged strike like this. The union leadership decided, okay, we need to move into a new phase. We need to try something different. We need to do something to force the company to move because they'd been stonewalling them for months, so they decided, okay, we're going to send the boys back down into the mine and try and fight this out at the bargaining table and perhaps via different legal measures.

The return date is slated for March 2nd, and I'm going to head back down there for that just to see what goes on because I'm very curious to see after two years and this treatment from the company, how many of the miners want to go back at all.

Melissa Harris-Perry: On exactly that point. You talked with one miner, Braxton Wright, who's not sure whether he wants to go back to the mines. Let's take a listen.

Braxton: So many people from our local government to the local news, to the NLRB, to the National Labor Board, to the most pro-union [unintelligible 00:10:44] president and labor secretary that we've ever had to not even mention us. Yes. It felt like we were just abandoned by everybody.

Melissa Harris-Perry: How representative is Braxton there of other folks?

Kim Kelly: [chuckles] I think it's going to be a pretty wild meeting when I get down there next week. I think people are mad, they're disappointed, they're upset. I've seen coal miners' Facebook, it's pretty intense. I've seen a lot of posts from people who are really angry at the company. Some folks are angry at union leadership. I think there's perhaps a little bit of a lack of information and people are upset about that. It's all a lot messier than it seems like it needed to be. I have to trust for just the sake of staying positive and staying hopeful that the union has a good strategy in place and that the workers will win in some way, shape, or form.

Right now it's difficult to see what the path forward is going to look like, because like I said, Braxton has another job that he's getting paid like $7 more an hour than he would be in the mine. He has two kids. There's people that depend on him and he has to take that into consideration. I think a lot of folks are in that position where maybe they found something that makes sense for them and their family. After being treated so poorly by your employers to go back without a solid contract on hand, that's a tough ask. It's still a developing story. We're going to find out more about what happens in the next couple weeks. It's a disappointing way to end the historic strike I would say. I really wish it had gone differently for everybody's sake.

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: Stick right there. When we return, we're going to have more about the Warrior Met Coal miners and their efforts to win a fair contract.

We're back with more updates from independent journalist, Kim Kelly. We're talking about the Warrior Met Coal mine workers who've been on strike for the past 23 months in Brookwood, Alabama. Some of the workers will be returning to work on March 2nd without a new contract.

It's interesting as you talk about wanting to hold on to that sense that the miners can win in some way. Not only have you been covering this story as a journalist, but you did write a book about where you build on and contextualize this moment in labor history in a much longer one. Look back on that for a moment, and tell me whether or not your optimism is least in your own assessment at this point well placed when it comes to American workers

Kim Kelly: In terms of American workers, broadly speaking, absolutely. I may be a Pollyanna, but I'm not a dummy. [laughs] Like you said, I wrote a whole book of my labor history. Even if you lose an individual strike or lose individual battle, we're still part of this longer entrenched war, and there's still more wins to come. I think so many of the successes that we have seen, the victories we have seen, the progress we've seen have built on the work of years and decades, and generations that came before. Sometimes if you go on strike and you win, that's great, but there's a lot of people that had to work really hard to get you and your union, and just the moment you live into that point where you can win.

When it comes to workers in Alabama, it has been so painful to see the way that these workers have been written off and abandoned, and stereotyped. That's something that is not new for workers in Alabama, but Alabama itself has such a rich labor history that I think doesn't get as much credit as it deserves. Whether we're talking about the organizing that Robin D. G. Kelly goes into in his iconic book, Hammer and Hoe, or just the history of mine workers in that state that goes back to 1890 and has always been District 20, which these workers are part of, has always been the most diverse sector in the UMWA.

There's so much that has gone into this strike, so much memory and history. Some of the people that were part of this strike, remember the Pittston strike of 1989, which was a similar brutal encounter but went differently. Some of these folks have grandfathers and fathers and even great-grandfathers who worked in these same mines. It's just the tale of it all so long and there's so much history the people are building on now that, if this strike didn't go the way they wanted to, all right, what's going to happen with the next one? What's going to happen with the next contract? What are the people that were part of this strike going to do with this experience?

I know for a fact that some of the women specifically who are part of the auxiliary, they've changed, they've taken on leadership roles. They're different than they were when I first met them two years ago when they would mostly say, "I'm so-and-so's mom. I'm so-and-so's wife now." Now, one of them, Hayden, who's actually married to Braxton, she's become a local democratic official. She's won elections. She is going to be a force. Without the strike, I don't know that she would've had the opportunity to spread her wings like that.

Melissa Harris-Perry: I love that reminder about how-- Again, in our history, we tend to not tell the stories of the failures that lay the groundwork for the successes. We just tell the mid-century civil rights movement story, we don't tell right or tell much less frequently or with less clarity. All of the so-called failures that came before, but which trained and implemented and created structures and frameworks for the thing that we think of as finally succeeding.

Kim Kelly: Right. Without Mother Jones back in [laughs] 1800, would the women of the Brookwood UMW auxiliary have felt as motivated and fired up, and supported as they did? They spoke about her all the time, and that was hundreds of years ago. Everything we do builds on something that someone else tried first. It's not an option to give up because then where we can go? You can't break the chain even if some of the links are a little bit rustier than others.

Melissa Harris-Perry: For those who are returning to work, do you have a sense of what their top concerns are and the ways that the solidarity that they've built, how they may be able to enact and engage and remain in solidarity even as they return?

Kim Kelly: I think that folks are concerned about the treatment they're going to receive because they stuck with the union. They didn't cross the line. I know that folks are worried about retaliation from the bosses that work there. I'm concerned about what's going to happen when you take, I think at this point there's 600 folks left. We take 600 coal miners who are feeling pretty emotional, spent two years on strike, and then send them down into the mines that still have replacement workers working in those jobs, and turn out the lights and leave them alone and see what happens when people come face to face with the folks that cross their picket line and spit in their face. It is a potentially volatile situation that if I was one of the people trying to negotiate and resolve this conflict, I would want to do it pretty quick.

Because I don't think it's going to be a good situation there. I feel these folks know that they've done something historic. They've built something important. They've built a real strong community. Now, these folks have spent Christmas together. They've shared groceries, they've shared childcare, they've shared a lot of beers. I think that it's really brought people together in a way that perhaps wouldn't have happened without this strike. There's something to be said for-- What is it? Making friends in a foxhole [chuckles].

I think that this is going to be an important chapter in all of their lives, and I know the women and the folks who are involved in the auxiliary, those relationships aren't going away. I guess it's a little early to see what happens. I hope that they feel like they have won something, whether it's new friendships, or renewed sense of pride in their union, or just the knowledge that they are part of this long line of coal miners who fought back and refused to bow their heads when the boss tried to take away their rights.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Kim Kelly has been covering the Warrior Met Coal Strike since April of 2021. An author of the book Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor. Kim, thanks for updating us and for joining us on The Takeaway.

Kim Kelly: Thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate you guys.

[music]

[00:20:10] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.