Larissa Fasthorse On Finding the Humor in Performative Wokeness

[music]

Jay Cowit: Hey, this is The Takeaway, I'm Jay Cowit in from Melissa Harris-Perry.

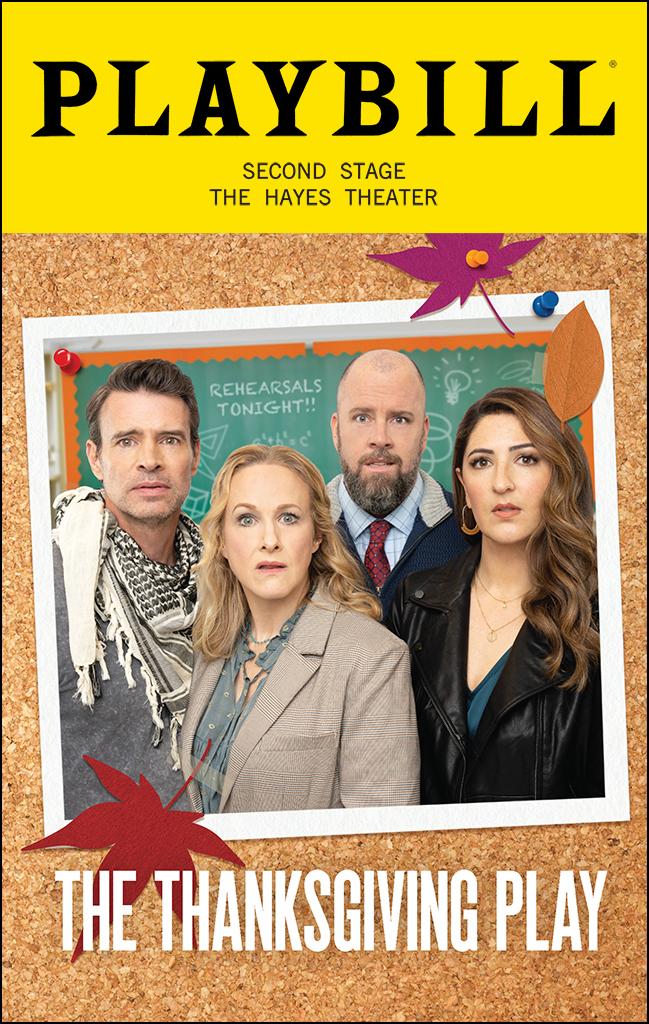

In The Thanksgiving Play, four white protagonists sit down to create a politically correct and historically accurate Thanksgiving play for a local elementary school. What could go wrong right? Well, the play explores the complicated and oftentimes, failing relationship between allyship and performative wilderness.

Larissa Fasthorse: I'm Larissa Fasthorse and I'm the playwright for The Thanksgiving Play and a member of the Sicanu Lakota Nation.

Jay Cowit: Larissa Fasthorse is one of the very first indigenous women to have a play produced on Broadway. She joined The Takeaway to talk about her Broadway debut, navigating theatre spaces as an indigenous playwright, and the complex failures of "well-meaning white people". Larissa, thank you so much for coming on.

Larissa Fasthorse: I'm thrilled to be here. Thanks, Jay.

Jay Cowit: First of all the play is opening up today on Broadway. How are you feeling about it?

Larissa Fasthorse: I am really excited. I'm thrilled to have this play launching into the world. It's always bittersweet for a playwright because the day after opening I head off to my next show, so the exciting birth on launching of the play is also the last time I see it, so it's a little sad also.

Jay Cowit: For those not familiar with the show, it revolves around four white characters who are trying their very hardest to put on a Thanksgiving play, a Thanksgiving story. Trying their hardest to do it right by what they think are the interests of Indigenous people or native people. They fail quite a bit throughout the play. I'm interested where you got the concept from.

Larissa Fasthorse: Yes, I mean, honestly, kind of was born out of my own failure. I had been writing plays for about 12 years, with a lot the indigenous characters in them and I was not getting them produced more than once by the commissioning theater because people kept saying my plays were uncastable and it was so frustrating. For me to finally break through and get my plays produced wider, I had to resort to writing play that had for white presenting folks, but still dealing with Indigenous issues.

What's more obvious to deal with Indigenous issues and Thanksgiving, and something that I felt like we can all relate to and feel like we know something about. My goal with this was to be able to still talk about native issues and, honestly, kind of blow up a holiday that we all love, unfortunately, but allow people a different way to look at it, and find new ways to celebrate it in a more accurate fashion.

Jay Cowit: As you're saying, no Indigenous actors in this cast. You kind of make the audience kind of live in a Native point of view. I'm interested in how you as a playwright, as you're writing this do that. Center Native American issues without having any Native American characters in the play?

Larissa Fasthorse: Yes, obviously, partially like I said from the topic, but also I've told people, they think I'm exaggerating, but I really don't think I am, but 80% of the lines in the play are just taking my life. They're taking from my experiences working with a lot of well-meaning white folks, every day of my life in theater, and just in the world. It's something that's with me always. It's the core of my identity. It's just who I am being a Native American woman here in this country. It's a political identity. It's a racial identity, it's a cultural identity.

It's my name. It's not something I can hide from, so it's always front and center and the things that people say and the way that they erase those things, or turn themselves som pretzels to try to interpret what they think that means being a Native person and the ways that I'm endlessly ignored or overlooked or miss spoken about right in front of my face, is kind of just perfect for theatre. I just captured it all. Stuck a bunch of fun jokes and storytelling in between, and there we had a play.

Jay Cowit: How much of the characters in the play that the well-meaning white people do you think are kind of reflected by the audiences that will see the play on Broadway?

Larissa Fasthorse: It's interesting though because Broadway is definitely a broader audience. There are people coming from around the world. It's a global audience. I meet people from different countries every night. There's people that come in that just stopped at TKTS a block away and got some last-minute tickets. They have no idea where they're coming to, they're maybe not even regular theatergoers. That's really exciting. That's a privilege to have that broad of an audience. Then I also have to think about, "Yikes, how is this going to land with them, and what can I do?"

The whole team, Rachel Chavkin, my director, all of our fantastic actors, our designers and myself really thought about it specifically this production as a Broadway production. There were changes made to everything. To the script, to the presentation to the design. We did a lot of work in the room together to make sure that this is something that I could use to speak to a huge audience and have it touch them in different ways, no matter where they're coming from.

Jay Cowit: Now, the play is very funny, but there's obviously an attempt to show maybe some cringy moments from these well-meaning white people and immerse your audience in that and not really let them out, even through the end of the play. Is that something that you are worried about at all for audiences that may not understand or not quite get the satire that you're trying to throw at them?

Larissa Fasthorse: Some folks I'm worried about that. I don't. Not everything is for everyone, and that's okay. You try to please everybody, you're going to fail. It's just not possible. However, at the same time, I'm a pretty good comedy writer. I've got six comedy plays being produced this year. I can write a joke pretty fast and pretty well and that hits with everyone. I have a lot of what I call unifying jokes that are for everybody. I know that I can make the comedy work. We have comedy genius actors. I know that that works. That that'll always catch people and get them caught up again, if they get lost in the satire at moments.

Also, a lot of the satire or the things that people call difficult or rough, they're just truth. It's literally all I'm doing is I took writings from actual pilgrims/separatists of the time, and I just told their story as they wrote it down themselves. It's not news to the Native people. We know these stories, we live them, and they would pass down through our families from person to person. They're just truths. They're just things that actually happen. It's interesting when people-- Sometimes folks are like, "Oh, will the Native people be okay with this?" It's like, "Oh, this is not news." If the white folks aren't okay with it, that's okay. It's time for them to learn their own truth that they wrote down themselves.

Jay Cowit: Plainly, a lot of this is kind of about the performative sensitivity among a lot of these characters and stuff that you've seen in your life. How do you define the word woke?

Larissa Fasthorse: Honestly, so I will say first off that I think that there's a lot of pushback now against using the word woke from all sides. I would say, I want to shout out to a lot of folks in Black culture, they're like, "Okay, this is our word in the first place, that's been appropriated by a lot of people in a lot of inappropriate ways." I want to shout that out, first off that it did come out of a specific American culture. For me, I think-- I hope I'm not woke at all, just in the way that wokeness is portrayed in this country by white folks just kind of ruined it.

Then also from apparently-- Again, I don't read a lot of these things, but I've been told is it's used a lot against folks too as a weapon to mean negative things. I'm actually a fan of the word myself. I think it just means people are-- I really do think it means people are trying really hard to be kind and considerate and to be aware of their place in the world and how they perhaps are centering themselves.

I think it's about people trying to look around at their privilege. Where do they have privilege in each room and space they're in and where can they help balance that out? For those that don't have as much privilege, which changes in every moment. There's rooms where I have no privilege and there's rooms where I have all the privilege. I think it's people trying to do that, but it's been misappropriated and used in a lot of negative ways.

Jay Cowit: I want to go to the performance now and kind of the production of the play. You have Rachel Chavkin directing and this is a play that's all conversation. It's dealing with a lot of awkward pauses and people reacting to these concepts and these in these moments. Tell me about how you as a playwright, and how you work with the director to get that right and get these conversations feeling naturally cringy.

Larissa Fasthorse: Yes, it's funny, because there's a combo of things. Theater is a collaboration. Rachel and I have known each other for 10 years. I'm thrilled that I'm making my Broadway debut with her. She's making her Broadway straight play debut with me. That's really fun that we get to do this together after knowing each other for so long and admiring each other's work. We work very collaboratively in the room. I mean, we're there side by side from the very first design meeting. From all the casting every day in the room. Through all the previews, tech. We do it all together, side by side.

We make all our decisions together, we really-- We each have our own lanes, of course. I do the typing and she says the standing and talking and all those things, but we really work hard to make sure that all the rooms that we're leading together are being led as a collaborative space. That means that everybody's contributing to what you're talking about. To that final product. The designers have ideas about moments about silence about, "Oh, you know what? Actually, shouldn't be a silence." There's this weird little hum that you probably aren't even aware of consciously that's happening through the theater at different points.

The sound designer, Mikaal Sulaiman, has put in are just making us feel little unsettled on a real visceral level that you don't even necessarily register. There's all these little things that are being put in. Then really the final piece is the actors. They're coming in with their incredible comedy and drama chops. It's really a matter of picking and choosing how to I'm not sure I say calibrate everything together to make those moments of incredible awkwardness, those moments of incredible drama, maybe some shock, and awe.

Then also moments of real comedy and release and fun and enjoyment together in the theater. These actors are so talented. They could make everything funny or make everything dramatic, and it could be a six-hour play. Instead, we had to pick and choose where do we want to release? Where do we want tension? Where do we want fun? Where do we want to just learn something? How do we pack that all into 86 minutes?

Jay Cowit: Love the shout-out to sound designing and subtle sound designing. Big fan. Let me ask you about what is essentially the fifth character in the play, which are the interstitial videos that play throughout. For the audience out there, these are pretty much parodies of children's holiday songs. These videos are absurd and horrifying in a way. You watch them and be like, "Oh, well, that's extreme satire." There's a lot of reality in them, isn't there? This is stuff that you've heard before.

Larissa Fasthorse: The videos are taken directly from teachers' pages on the internet within the last 10 years, so they're all current, they're all word for word. What teachers are having children do on pageants, on chat boards with ideas for Thanksgiving, on their Pinterest boards? All the comments are directly from teachers and public people on these websites. I didn't write any of that. I did condense it. For some reason it was 10 days of Thanksgiving instead of 12, but I don't know. We did nine, I don't know why that just seemed the right amount of relentlessness.

I did rearrange the song a bit for a dramatic build. I did with the Four Little Turkey song and the 10 Little Indian songs, I put those two songs together. Both songs though being taught on websites for children as great songs to have your kids sing in the Thanksgiving season. Like I said, all the comments are directly from there. The curriculums they talk about are also from the Internet. Everything is real. My publisher just made me change all the websites to protect everybody.

Jay Cowit: All right, Larissa, quick intermission right here. We're back talking more about the Thanksgiving Play on The Takeaway right after this.

[music]

All right. We are back. We're talking with Larissa Fasthorse playwright of The Thanksgiving Play, which comes out on Broadway today. Throughout the play as the characters on stage go through this, they get lost in their own lives and feelings and their own experiences or what they believe their experiences mean to this particular production. They become borderline unhinged at various points trying to deal with this. Talk to me a little bit about the absurdity of performing wokeness specific to these characters. Is there any empathy towards their "struggle" here or is this showing people that they're most extreme uselessness in terms of doing this play?

Larissa Fasthorse: That's the thing with theater. You don't pay your money and leave your house and have dinner and come out to watch Saturday. You know what I mean? You come out to watch the most crucial moment of people's lives. This isn't just Saturday. This is a crucial turning point in all of their lives for their own reasons. To some people they may seem very small doing an educational play for kids around Thanksgiving may seem small to some folks, but to these people for various reasons, it's really important and it's the most important thing in their lives. Obviously, that's the first part. That's what we come for is that that day when everything changes.

Also, I'd say that's life. It's so wild. On one minute you're deep in something very important, your work and your job and whatever, and the next minute you get the text like I got last night actually that my 92-year-old mother had tripped and fallen and had to race over and take her to the ER. Suddenly you're in this absurd ER story that I could write a whole play about. That's life. It's switching, pivoting so fast from thing to thing. My job I think as a dramatist is how do I capture, I would say I try to write at the speed of life. How do I capture that speed of life and put it on a stage in a way that works in that space? This suspended disbelief space that we're all agreeing to when we walk into a theater.

How do I make sure though then also at the same time that life affects each of us? It does get pretty absurd. It does get pretty wild because we're catching these people on their worst or best day, depending on the play. This one, I think I'd say is probably they thought it was good, their best day, and it turns out to be their worst. That's my job. It's the dramatist. How do I take that and get us to still identify with them? There are some very personal moments that happen in this play because that's what happens in life. As crazy as things get suddenly you're in the fight with your boyfriend about ridiculous things.

Then you get back trying to save the world through children's pageants, which is absurd, of course, just in itself. I do love these people and I love their humanity, and I love how-- I hope all of us, including myself see ourselves at times in these people and be like, "Wow, that's awesome, or that's really horrifying, and I need to think again about why I do these things and why I can see myself in them."

Jay Cowit: Speaking of really horrifying, there's a point in the play, I think you probably know where I'm getting to here. Perhaps if there's any empathy, it might be lost, where the characters decide to act out the Pequot massacre of 1637 in an extremely visceral way and with a reminder that they're making a play meant for elementary school students. I'm interested in how you're showcasing how much of the American Canon of indigenous and native stories are wrapped up in violence.

Larissa Fasthorse: That's the problem. Ultimately, if you're talking about anything with us as indigenous people, if you're talking about anything historical, 90% of it is horrific. The violence that's been perpetrated on us by first the original settlers and invaders, and then the various governments depending on what part of the continent you're on, it's been the British government, the American government, the French, the Spanish, the Mexican. All these different governments had parts of this land and have done horrific things by law against indigenous people. All of that is always there. However, the part that I love is the last 10% is that we survived.

Not only we survived, we thrived. We had the "greatest nation" on the planet have been trying to eradicate us for centuries and we're still here. Not only are we here, but we're dealing with it with comedy and humor and love and pride and culture. That's amazing. We always say if you get two native people together within minutes, even if they've never met each other, they're laughing because we're living the longest black comedy on the planet and we can still laugh and survive and thrive. There's that part of it. I feel like my writing, yes, there's some horrific just plain up truth like you were talking about the Pequot massacre that we do talk about.

It's actually a relief to a lot of native people to have us just say it out loud, this is what happened just like this. It is pretty visceral when you see it in the play, but it's actually just the truth. Then it's a relief for us to have someone finally say it out loud. It's like, "Okay, this is what we're talking about. If we're not dealing with what actually happened, how can we ever move forward? Okay, let's deal with that. Let's talk about it, and now we can move forward and then we can have a ridiculous scene where we laugh about a fight with our boyfriend because we're all human and we're all people who get in fights with our boyfriends."

We can relate to that together as a group and say, "Okay, we have these extreme differences that may make us uncomfortable, but then we also have these similarities." My hope is that in this play, even though I can be pretty tough on the well-meaning white people, they realize that I want us to all see each other as human and go forward together.

Jay Cowit: A spoiler alert here for people who haven't seen it. At the end of the show, the characters decide that it's pretty much better to do nothing than attempt to do this and have this difficult conversation. Do you have a take on that? Is it better to do nothing or is it better to work through these ideas?

Larissa Fasthorse: Obviously, I want people to work through things, but also there is a place. The ending of this play came directly from a talk I had with a white male artistic director when I was working on the play at Playwrights Horizons before the pandemic. He was our super well-meaning liberal white person, [laughs] like our characters. He said to me, "Larissa, I finally figured it out. I've been trying so hard. I've been trying to do all the right things. I've been trying to be involved in the EDI conversations and equity and diversity and inclusion. I've been trying to do all these things and I realized I just need to stop. As a white male, I just need to do nothing." I was like, "Okay, what does that mean to you?"

It didn't mean giving up his six-figure salary. It did not mean giving up his benefits. It did not giving up his gatekeeping of everything that happens in his theater. It just meant keeping all of that, the money, the power, and doing nothing. I was like, "Wait, Phil, that's not how it works at all." [laughs] Of course kept my mouth shut because I want him to keep talking because I needed to write the end of my play. I was like, "Really? Tell me more." There's doing nothing because you want to create room for others and there's doing nothing because you're abdicating but keeping all the power and those are very different things and I hope that people think about which one is appropriate for them.

Jay Cowit: Sure. On the subject of power, you are now on the front lines in terms of indigenous theater folks to have a play produced on Broadway. What does that mean to you, that moment, that power, that responsibility, that honor?

Larissa Fasthorse: Yes. You said it perfectly [laughs]. It is all of those things in every moment. It's hard. It's constantly conflicting, right? Lynn Rigs, the great Lynn Rigs had many plays on Broadway, but it was at the beginning of the last century, right? We're at the beginning of the next century before we've had another Native American playwright on Broadway that we know of. That's not okay. That's horrifying, right? Then I also try to stay with, yay, I'm here and I love this play and I love this process and I love the incredibly diverse audiences second stage has worked with us to build, I love that I'm getting to have this voice with people all over the world and with people like you.

That's awesome. It's exciting and it certainly is, something I've been aiming for in my career for a long time. Personally, it's great and amazing and I love the show so much. Then, I have to say it is a huge responsibility. I'm always thinking it cannot be the next century before we have another native playwright on Broadway. It just can't. There needs to be one next year. There needs to be one every year. We're so far behind. There's a lot of responsibility on me to feel like I need to make sure the door wasn't just open for me. I need it to stay open and then the theaters to be going through that door, pulling more native writers and performers in.

I'm really constantly working on that, working with a lot of folks behind the scenes to make sure we're getting to native audiences. We're bringing tons of native youth from all over the country. I've gotten some incredible donors giving a lot of their personal money to bring native youth that I've worked with in theater camps or the native theater programs around the country to this play in New York. It costs a lot of money to bring a bunch of kids to New York and they're doing it and they're bringing them in and that's exciting. I'm like, "Great, this will be our next generation that assumes they're supposed to be native people on Broadway because that's what they grew up with."

I'm always with all these amazing native artists. Then at the same time, there's this fascinating know, I'm excited for me and this work and the fact that I have five more plays this year that now all have native casts. That's incredible. That's something I couldn't do before this play. Then I had a good friend of mine, Kenny Ramos, he's an indigenous actor that came all the way from California, spent 18 hours here to see my play, spent the night on my couch. We got home from the show and we jumped up and down. We said, "We made it. Like we made it."

We were like tearful because it is, we, when you're an indigenous person, sure I don't have to represent everybody, but at the same time it's we, and I'm so honored and take that responsibility so strongly that I'm always a part of a, we, and that we have made it to Broadway and we want to stay here.

Jay Cowit: Really well. You talked about getting more indigenous actors into plays coming up this year. Tell me about what's coming up.

Larissa Fasthorse: Yes, I'm so excited I have, so this is play number one of six. Next play I'm doing is with Tune with Cornerstone Theater Company in South Dakota. We're doing a tour of five reservations where I'm from. It's going to be a cast of Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota people. I'm so excited the play we all created together, that's a Native American superhero play, a Lakota superhero, which is really exciting. Then we go next, I come back to New York and I do this democracy project at Federal Hall with a whole bunch of amazing starry writers. Michael L Jackson wrote a song for it.

Then I go back to LA and I do my new farce at the Mark Taper form. It's a brand new satirical farce talking about race and [unintelligible 00:25:19] and race shifters. It's an interesting little exploration with a lot of ridiculous sparse funniness. Then I go to the Guthrie with a play I co-wrote with Tifo called For the People. That's another comedy based in the Twin Cities Indigenous people from there on the main stage. Then I come back to New York for Peter Pan. That's, I finished the year with my new version of Peter Pan based on the well-known beloved Jerome Robins Broadway version being updated with indigenous characters for hopefully the next century.

Jay Cowit: Larissa, thank you so much. Thanksgiving play opens on Broadway today at the Helen Hayes Theater. Larissa Fasthorse is the playwright for the Thanksgiving play. Thank you so much for the time today.

Larissa Fasthorse: Oh, it's been so great speaking with you. I really appreciate it.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.