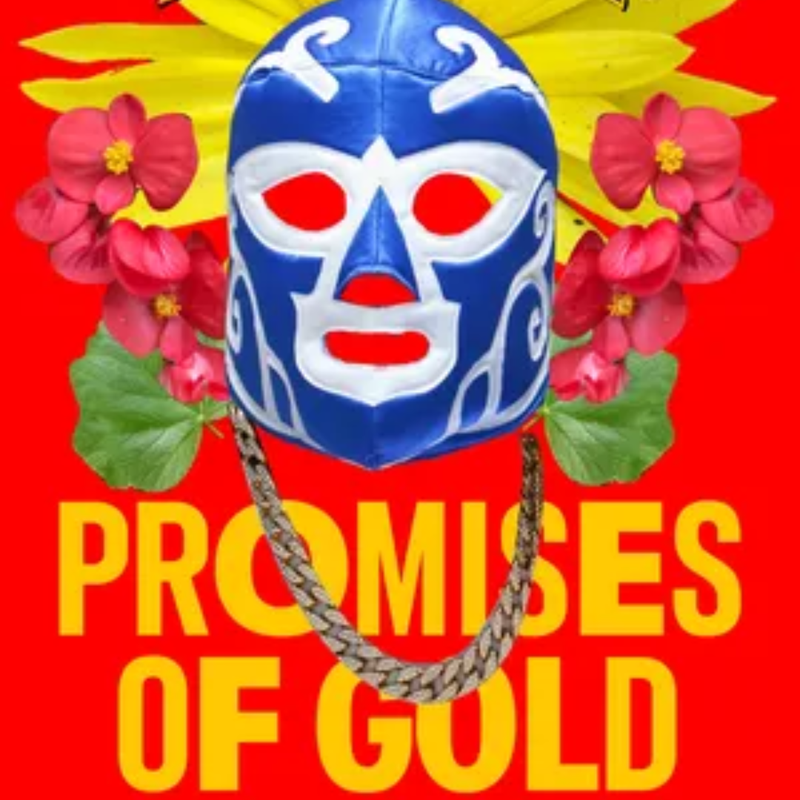

Poet José Olivarez Discusses “Promises of Gold”

( Henry Holt & Co )

Melissa Harris-Perry: Welcome back to The Takeaway, I'm Melissa Harris-Perry.

In 2018, the debut collection by a young Mexican-American poet, burst into the literary world. The Chicago Tribune described the book titled Citizen Illegal as a "Boisterous, empathetic, funny-yet serious, but not self-serious celebratory ode to Chicanx life in the contemporary United States. Citizen Illegal won the 2018 Chicago Review of Books Poetry Prize, and now the author, performer, and educator has published a second startling collection.

José Olivarez: My name is José Olivarez author of Promises of Gold.

Melissa: The proud son of Mexican immigrants, Olivarez's newest collection Promises of Gold is a dual language exploration of love in its many manifestations, and the distinct loneliness of straddling the hyphen between Mexican and American.

José: Wealth, don't talk to me about wealth. When I got into Harvard my guys joked it was to mow the lawns. I laughed until I met my roommates and they offered me a broom. If I accepted the broom and beat the cobwebs out of their heads, do you think I'd forget? Now I make poems in languages they can't register. You feel me? In every poem, I had garden shears. Invitations to banquets and they still don't spell my name right.

Melissa: Here in these poems love is not reserved for the romantic. Olivarez contemplates the love of countries, cultures, family, and friends, and with unflinching insight the complicated challenge of loving the self.

José: Apologies, when they say José, the only people to turn their heads are me, and the janitors, line cooks, wait staff, yes, landscapers, José El Poeta, El José The Gardener. Each of us biting our tongues trying to make beauty grow from soil covering bones, barely under the surface. Promises of Gold is a collection of poems that began during the pandemic when I was really missing my friends as we were scattered all over the country.

As I sought to write a book of love poems I found that a lot of sadness, and grief, and also all of the political situations that we were going through were leaking into the work. Promises of Gold what I decided to do was instead of turning away from the reality of the world, continue to try to write love poems that soaked in all of the real-life situations that we go through to give the poems texture and nuance.

Melissa: For José, the pandemic was a reminder of other pandemics, suffered and survived by those he loves. Not the pandemics of contagious respiratory disease, but those that stripped communities of resources, ignored the needs of families and left so many to figure out how to build lives of meaning and connection.

José: First and foremost a lot of the way that I view the world and respond to the world is guided by the fact that both of my parents migrated to the United States from Mexico. That migration is a massive one and has shaped not just our political reality, but also our interpersonal relationships. How do we try to build a family life of love while also grappling with all of the silences that we've had to hide from each other either because we speak different languages? In my parent's case because they were trying to keep our family safe from immigration forces and things like that.

Another one is I grew up in the south suburbs of Chicago a town called Calumet City and lived through a process of white flight that really left our schools wrestling without the resources that they once had. All of those different things have helped shape in our pandemics alongside, of course, the Coronavirus pandemic that we've been living through. I would set out with one intention to write a love poem for my friends back home in Chicago. Then, of course, the language would move me subconsciously towards obviously the uprisings of 2020 in moments like that.

Rather than view them as a distraction or try to erase those thoughts, really what I tried to do was think about like given the reality of the world that we live in. What does it really mean to be in community with people across different political communities, ethnic identities, racial identities, sexual orientations? How can I show up for my friends and really be there for them? Really put myself in a position where not only am I writing love poems, but I'm really trying to embody the life that I'm putting on the page.

Melissa: For José embodying this truth means living and writing at La Frontera, the Borderlands, where language and meeting collide.

José: I've had the opportunity to teach poetry workshops across the United States in both English and in Spanish. Whenever I teach workshops bilingually the parents always come up to me and they tell me that they really enjoyed the workshop and they wish they could read my poems, but they don't read or write in English. I had them in mind.

Then I also thought about what it was like when I was a young person growing up in the world and I couldn't share the work that I was doing in school with my parents because they also did not speak or write in English. For me, it's just important because in some ways to me it's not multiple audiences, it's one audience that doesn't usually get access to literature in this way.

Melissa: Stick around we've got more with José Olivarez after this break. It's The Takeaway. We're back with The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry, and we're continuing our conversation with Mexican-American poet, performer, and educator José Olivarez. We're talking about his latest work, Promises of Gold. Now, Promises of Gold is a dual-language poetry anthology. Divided into two parts the collection offers each poem in English and Spanish.

This division within a single hole is both a practical matter of accessibility and a physical representation of the divided self that Olivarez's work has long explored. For José, much of his experience as a Mexican-American has nestled in the in-betweens, and the poetry of this borderland conveyed across both languages, honors and reflects those experiences.

José: I was hoping that by putting them both in the same addition that maybe families could read the poems together, could share that experience, could read the poems first in English and then read them in Spanish together or vice versa. Like I also really believe that the work it's almost like reading two books. The experience in English and Spanish they're the same poems, but the textures are slightly different. The music is slightly different. I'm really excited to see how people really use the book. This is my first time releasing a book in both Spanish and English. I'm as curious as anybody else to see how people use both editions, and the fact that they're together in one book I really hope makes them accessible.

Melissa: Now, Spanish is José's first language but the art of translation is much trickier than just knowing the exact vocabulary in another language. It's about communicating the feelings, the ideas, the subtleties, in ways that resonate in both tongues. This is not the work of some AI-generated translation, José worked closely with David Ruano. For a poet who carefully considers each and every word, working with another writer developed new skills.

José: Experience working with the translator was one of revelation for me. Obviously, I know my poems and the way that I wrote them, but to get to see them through David's eyes who's the translator was a really special experience. I remember when I first read those translations getting really emotional because Spanish is my first language. It's a language that I don't get to practice in as much because I went to schools in English here in the United States, and so I feel the translations helped me reconnect to part of my culture and part of my own inner mind.

Melissa: For José making his poetry fully accessible across English and Spanish in the same anthology it felt like almost an act of resistance. His own history of navigating these two languages more battle than ballet.

José: When I was five years old and looking to enroll in Kindergarten my mom took me to the local public school. Before I was allowed to enroll the principal called me into his office and made me have a meeting with him, my mom, and a translator, and basically made me promise to learn English. You can imagine for a kid the principal's office is not somewhere you want to be. The principal's office means trouble and here I was my very first day as a five-year-old and it already felt like I was in trouble.

My hope and one of the reasons why language accessibility is so important to me is because I really believe that people should have the choice to read and write in all of their languages. I don't think that they should have to cut off part of their existence to please English-speaking teachers or anything like that. My hope is that the book will find its way into the arms of bilingual readers and hopefully spark some recognition and some curiosity out of young readers.

Melissa: In the pages of his latest anthology, José has chosen to love and be loved in both languages. In his poetry love looks a lot more accepting than the world around him ever has.

José: When I was growing up as the child of immigrants it really felt like I didn't fully belong in any one place. When I was at school I had to hide or I couldn't fully be myself. There were parts of my existence at home that either the students couldn't relate to where I was going, or they couldn't understand the language. Likewise, when I went home there was only so much I could tell my parents about my existence at school because they didn't speak English and they weren't there or hadn't gone through that experience.

My parents couldn't help me with history homework. They couldn't help me with math homework. They did their best to put us in a position to succeed but it never really felt I belonged in those times. I write towards the possibility of what it might be to fully inhabit oneself in different spaces and to really try and see oneself as not having to hide in order to belong in any given environment. For me writing love poems is an act of healing of attempting to heal, of attempting to really cherish and sing love songs to all the different parts of myself that I really treasure and want to shout out.

Melissa: Throughout Promises of God Olivarez reflects on what love is, and those are the reflections that pushed him to understand the experience in a brand new way.

José: One of the most important books to me in my young adult life has been the book All About Love by Bell hooks, and my big takeaway from that book was thinking about how love is in action. Love as a verb, not a noun necessarily. I think my big takeaway with writing this book is that I used to think that love was enough to solve all my problems.

I think by writing this book I found that love is great and it's important, and I really try to embrace it in all the ways that it shows up in my life. At the same time living in the world and being in relationships with people really require us to commit to one another, and so I think writing the book has taught me that love requires action and more than that consistency. It requires us to continually to show up for one another, and so I think that's been one of my big takeaways writing, Promises of God.

Melissa: A note of thanks to my colleague Janae Pierre who talked with José Olivarez. Poet, performer, and educator José's dual language poetry collection Promises of God is available now.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.